Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a physically and emotionally debilitating skin condition affecting up to 630,000 people in the UK[1],[2]

,[3]

,[4]

,[5]

(around 1% of the population) the prevalence of CSU is thought to be increasing[3],[6],[7],[8],[9]

. Although rarely life-threatening, chronic urticaria causes both misery and embarrassment, and has an impact on an individual’s quality of life (QoL), comparable with severe coronary artery disease[10],[11],[12]

.

Urticaria is one of the most common reasons people seek medical advice but it can take up to 18 months for a diagnosis because of diagnostic challenges and unclear referral pathways to a specialist[1],

[2],

[5]

. Where patients are managed in primary care, many do not experience appropriate escalation of treatment when first-line therapy fails, resulting in low patient aspirations for optimal control of their symptoms.

The ‘Wheals of despair’ report, published in 2014, highlights the main challenges of CSU, such as lack of specialist knowledge of the condition in primary care, delays in referral and correct diagnosis, lack of psychological support for patients, as well as lack of access to efficacious treatments and clarity regarding treatment options[1]

. This article focuses on the diagnosis and management of CSU in primary and secondary care, and the role of pharmacists in improving the standards of care for these patients.

Urticaria (also known as hives) is characterised by a red, raised, itchy whealing rash, with or without angioedema. The major feature of urticaria is mast cell activation that results in the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators (see ‘Figure 1: Mast cell activation’). There is subsequent vasodilatation, increased blood flow and increased vascular permeability presenting as hives accompanied by intense pruritus. Angioedema is the result of a local increase in vascular permeability, often notable in the eyes, lips, oropharynx and gastrointestinal tract[5],[13]

. CSU is the most common form of chronic urticaria with more than 80% of cases being spontaneous; the remainder are inducible[14]

. Although the precise mechanism that triggers the activation of mast cells is unknown, CSU is defined as the non-inducible recurrence of wheals, angioedema or both, for six weeks or more[5],[13]

. Urticaria may occur alone in around 40% of chronic urticaria cases, in conjunction with angioedema in 40% of cases and as angioedema without urticaria in 20% of cases[15]

.

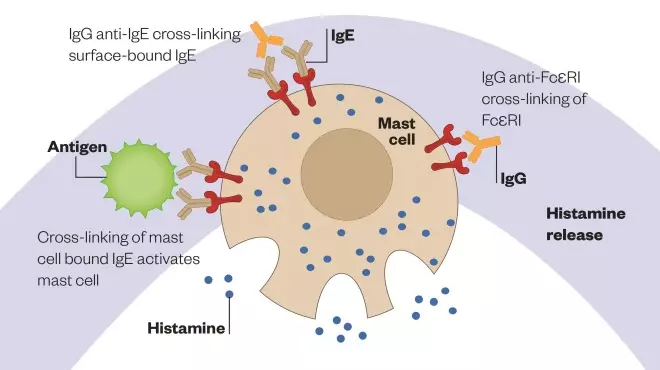

Figure 1: Mast cell activation

Schematic diagram illustrating the binding of antigens and cross-linking of immunoglobulin E (IgE)-receptor complexes on the mast cell membrane. This event triggers a cascade within the cell that results in the synthesis and release of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, as well as degranulation, which releases histamine, chemical mediators and other factors.

CSU can have an impact on physical activities, with nearly a quarter of patients missing work at least once a month as a result of their symptoms and 90% of patients saying their sleep is affected. Other patients report it impacts on their eating, choice of clothes, social activities, mental status (including fatigue, stress and anxiety) and finances[1],[16]

. CSU has an estimated duration of one to five years in most cases[3],[17]

. However, it has been suggested that from the time patients are diagnosed, 50% will continue to suffer after six months, 30% will continue to suffer after three years, 10% will continue to suffer after five years and 8% will continue to suffer after 25 years[17]

.

Types of urticaria

Acute urticaria is a single episode of an itchy rash lasting for six weeks or less, whereas chronic urticaria is defined as a recurrence of wheals and/or angioedema for more than six weeks. ‘Table 1: Clinical classification of chronic urticaria and angioedema’ lists the clinical classification of chronic urticaria and angioedema that should be used for diagnosis[5],[13]

.

Risk factors

Females are twice as likely to be affected as males. While all age groups can be affected by CSU, the peak incidence is 20–40 years of age. There is no apparent relationship established between prevalence and education, income, occupation or ethnicity[3]

.

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms

A hive is a central swelling, usually surrounded by a reflex erythema, and can vary in size from a few millimetres to hand-sized lesions, which may be single or numerous (see Photo guide). It is associated with itching or sometimes a burning sensation. Characteristically, the lesions of urticaria arise spontaneously and resolve within 24 hours. Angioedema (see photo guide) is a sudden, pronounced erythematous or skin-coloured swelling of the lower dermis and subcutis with frequent involvement below mucous membranes; this may persist for days[5],[13]

.

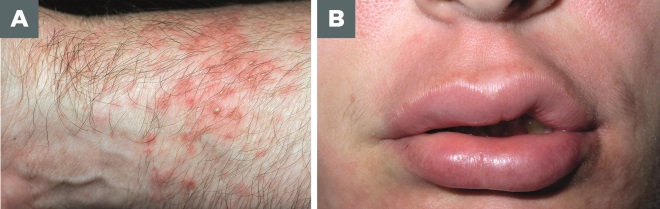

Photo guide: Hives and angioedema

Source: Alamy / Science Photo Library

A. Hives: central swelling, usually surrounded by a reflex erythema. Size varies from a few millimetres to hand size lesions, which may be single or numerous. Lesions arise spontaneously and resolve within 24 hours.

B. Angioedema: Sudden, pronounced erythematous or skin coloured swelling of the lower dermis and subcutis with frequent involvement below mucous membranes is classed as angioedema. This can last for days.

A full medical history should be undertaken to identify all possible eliciting factors and significant aspects of the nature of the condition, as detailed in ‘Box 1: Full medical history to identify significant aspects of the condition’[5],[13]

.

Box 1: Full medical history to identify significant aspects of the condition

- Time of onset of disease, frequency/duration of symptoms, diurnal symptoms, occurrence in relation to weekends, holidays and foreign travels;

- Shape, size, distribution and associated symptoms of lesions;

- Family and medical history or urticarial and atopic conditions, including allergies;

- Correlation with triggers (e.g. psychiatric conditions, food, allergen, exercise and medication use);

- Occupation, hobbies, smoking habits and stress;

- Previous diagnostic procedures and previous therapy and response to treatment;

- Quality of life related to urticaria and emotional aspect.

Sources: Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy 2014; Powell RJ, Leech SC, Till S et al. BSACI guideline for the management of chronic urticaria and angioedema. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 2015;45:547–565

Where indicated by the clinical history and examination, further investigations should be undertaken to exclude known causes and other conditions listed in Table 1. This could include diagnostic provocation tests (e.g. medications, foods, physical causes), blood tests (routine differential blood count and test for elevated inflammation markers, i.e. erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP]) and/or omission of suspected drugs. It is also important to rule out infectious disease, type I allergy, functional autoantibodies, thyroid hormones and autoantibodies[5],[13]

. Where hives are accompanied by recurrent unexplained fever, joint or bone pain, and/or malaise, acquired autoimmune diseases (e.g. systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult-onset Still’s disease) may be the cause[5],[13]

. Further investigations may be undertaken by a specialist in a secondary or tertiary care centre, when the primary care clinician has referred the patient.

Assessing severity and impact

Following diagnosis of CSU, the following validated scales are used to assess its severity and impact on QoL:

- Severity:

- Urticaria activity score 7 (UAS7): the patient scores their number of hive(s) (0–3) and pruritis severity (0–3) each day for seven days (‘Table 2: Urticaria activity score 7 scale’). The maximum weekly score is 42; the higher the score, the more severe the disease[5]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, has suggested the use of this scale[18]

. - Angioedema activity score (AAS): in patients with angioedema, the patient responds to an opening question and five additional questions on the severity of their symptoms over the past 24 hours. Results are combined over a seven-day period. Each item is scored between 0 and 3 points, with final weekly scores ranging between 0 and 105. A higher score indicates greater disease severity[19]

. - Urticaria control test (UCT): this is a four-item scale that assesses urticaria control in the past four weeks. Low points indicate high disease activity and low disease control.

- Urticaria activity score 7 (UAS7): the patient scores their number of hive(s) (0–3) and pruritis severity (0–3) each day for seven days (‘Table 2: Urticaria activity score 7 scale’). The maximum weekly score is 42; the higher the score, the more severe the disease[5]

- Impact on QoL:

- Dermatology QoL index (DLQI): this includes ten points on a four-item scale with a composite score of 30, but is not specific to CSU[20]

. - Chronic urticaria QoL questionnaire (CU-Q2oL): the patient completes a self-administered 23-item questionnaire indicating the extent to which they have been troubled by each problem (1: not at all; 5: very much). Higher scores indicate a more severe impact on QoL. This questionnaire is specifically designed for CSU[21]

.

- Dermatology QoL index (DLQI): this includes ten points on a four-item scale with a composite score of 30, but is not specific to CSU[20]

| Level of disease | Score | Wheals and pruritus |

|---|---|---|

| Symptom free | 0 | Itch and hive-free over seven days |

| Well-controlled chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) | 1–6 | Typically with a mild itch and no hives or <20 hives over 24 hours |

| Mild CSU | 7–15 | Typically with a mild itch and <20 hives over 24 hours |

| Moderate CSU | 16–27 | Typically with a troublesome itch and ≤50 hives over 24 hours |

| Severe CSU | 28–42 | Typically with an intense itch and >50 hives over 24 hours or large confluent areas of hives |

Treatment and monitoring

Currently there is no curative treatment for CSU, therefore, treatment aims to improve or suppress symptoms by inhibiting the release and/or the effect of mast cell mediators (e.g. histamine on H1-receptors)[5]

. The treatment regime should be modified according to response and development of any adverse effects. Once symptom control has been accomplished, daily treatment is advised in most patients for 3–6 months. For individuals with a long history of CSU with angioedema, treatment for 6–12 months is advised under the guidance of a specialist consultant in dermatology, immunology or allergy, with gradual withdrawal over a period of weeks. For patients with infrequent symptoms, treatment may be taken as required or even prophylactically (e.g. prior to significant occasions)[5],[13]

. For some patients, a short course (3–7 days) of oral corticosteroids may alleviate symptoms but should only be prescribed under specialist advice.

Step 1: Non-sedating H1-antihistamine

All antihistamines are licensed for use in CSU. Non-sedating H1-antihistamines (also known as second-generation antihistamines) are the preferred first-line treatment owing to a higher efficacy and duration of action[13]

. In addition, sedation and impaired psychomotor function associated with first-generation antihistamines is reduced. At licensed doses, non-sedating antihistamines fail to control symptoms in up to 50% of CSU cases, thus higher than normal doses (up to four-fold) may be required[5],[13]

. Incremental up-titration is recommended for doses above usual recommendations (i.e. increasing the recommended dose two-fold and then four-fold). Cetirizine dose, for example, can be 10mg once daily, increased to twice daily after two weeks and then 20mg twice daily if symptoms are still not controlled after another two weeks. If one antihistamine is not effective in controlling the daily symptoms, another should be prescribed to replace it. Up-titration with a single antihistamine is preferable to mixing different antihistamines. Prescribing and up-titration of non-sedating H1-antihistamines can be undertaken in primary care[5],[13]

.

Step 2: Add leukotriene receptor antagonist and/or consider alternative therapy

Up to a third of patients remain symptomatic, despite non-sedating antihistamine dose increase[3]

. Where H1-antihistamine therapy at optimal dose is not effective in controlling the symptoms, a leukotriene receptor antagonist can be added (e.g. montelukast 10mg once daily). Although not licensed for CSU, leukotriene receptor antagonist use is recommended in national and international guidelines[5],[13]

.

Alternative choices at this stage could be trialled by specialist consultants and include sedating H1-antihistamines (also known as first-generation antihistamines, e.g. hydroxyzine). Chronic use should be avoided where possible because of sedation and interference with psychomotor performance[5],[13]

. Some evidence suggests that a tricyclic antidepressant (e.g. doxepin 75mg) at night has beneficial effects. Doxepin is a potent H1 and H2 antihistamine, and also offers multiple receptor-blocking properties. It should be noted that use can be limited by sedative and anticholinergic side effects[22]

. H2-antihistamines were previously recommended but the supporting evidence is weak, therefore, their use is no longer recommended[5]

.

Step 3: Add anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) therapy or immunosuppressant therapy

Anti-IgE: omalizumab (Xolair) 300mg subcutaneously every four weeks

As IgE is main to the release of histamine and other pro-inflammatory mediators from mast cells and basophils, it is thought to play a role in CSU[13]

. In a third of patients with CSU, functional autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεR1) have been demonstrated, suggesting an autoimmune basis of disease[23]

,[24],[25]

. Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets IgE. It has been shown to be effective (with a maximum suppression of free IgE observed three days after the first dose) in 80% of CSU patients with persistent symptoms despite high-dose antihistamines[5],[26],[27]

,[28],[29]

,[30]

,[31]

,[32]

.

Pharmacists will need to ensure prescribing omalizumab for CSU is as per NICE recommendations (see ‘Box 2: NICE Technology Appraisal 339’). Before administration, patients should be counselled on CSU, how omalizumab works and the dosing schedule. They will also need to attend an outpatient clinic on a monthly basis, and understand potential adverse effects and the risk of anaphylaxis. On initiation, pharmacists will need to ensure UAS7 scores have been documented for four weeks to determine eligibility for treatment. Once omalizumab therapy has been initiated, pharmacists will need to ensure UAS7 scores are documented before administering the fifth dose to assess response. Following the sixth dose, pharmacists will need to assess whether the patient is in remission or if another course (six doses) is warranted[18]

.

Box 2. NICE Technology Appraisal 339: Omalizumab for previously treated chronic spontaneous urticaria

NICE recommends omalizumab as add-on therapy for treating severe CSU in adults and young people aged 12 years and older only if:

- The severity of the condition is assessed objectively, i.e. using UAS7 ≥28 for two weeks or more out of the four-week pre-assessment (see Appendix 1);

- The patient’s condition has not responded to standard treatment with H1-antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists;

- Omalizumab is stopped at or before the fourth dose if the condition has not responded, i.e. UAS7 ≥16 for one week prior to fifth dose*;

- Omalizumab is stopped at the end of a course of treatment (six doses) if the condition has responded. Spontaneous remission is defined by UAS7 ≤6 at the end of the course;

- Omalizumab is restarted only if the condition relapses, defined by UAS7 ≥16 at the end of the course;

- Omalizumab is administered under the management of a consultant in dermatology, immunology or allergy;

- The patient must be monitored for 30 minutes after administration for anaphylaxis.

*In exceptional cases, it may be appropriate to continue omalizumab in patients:

- With a UAS7 of 16–27 if the baseline score was in excess of 40;

- Who are steroid or immunosuppressive-dependent and unable to stop their treatment without severe symptom relapse and should be changed to omalizumab to minimise long-term risks of therapy;

- With a large angio-oedema component since this is not recorded on UAS7.

Source: NICE Technology Appraisal 339: Omalizumab for previously treated chronic spontaneous urticaria. September 2015.

Other Immunosuppressant therapy

Owing to unlicensed indication, high incidence of adverse effects and rebound or relapse on withdrawal, immunosuppressant initiation should only be undertaken by a specialist consultant in secondary or tertiary care[5],[33]

.

Ciclosporin (cyclosporine)

Off-licence use of ciclosporin (cyclosporine) with a non-sedating H1-antihistamine has been shown to be efficacious at a dose of 5mg/kg in patients with severe CSU refractory to H1-antihistamines (lower doses, such as 1.5–2.5mg/kg, have been utilised to avoid hypertension and renal impairment). The guidelines do not suggest dosing to therapeutic levels. Where prescribed, patients will need monitoring of blood pressure twice weekly and renal function fortnightly for the first two weeks, then monthly throughout therapy. If the serum creatinine increases by 30%, the dosage of ciclosporin (cyclosporine) should be reduced. If the creatinine does not return to baseline in two more weeks (i.e. after a month of increase, the decision can be made to discontinue treatment)[5],[13]

.

Mycophenolate

Off-licence use of mycophenolate with a non-sedating H1-antihistamine can be prescribed at a dose of 1,000mg twice daily in patients with severe CSU refractory to H1-antihistamines. Owing to potential adverse effects and intolerability, prescribing should begin at a low dose and should be increased incrementally every two weeks to target dose. It takes 6–12 weeks for it to be effective; a longer duration than with omalizumab and ciclosporin (cyclosporine)[34]

. Where prescribed, the patient would need weekly blood monitoring for four weeks, fortnightly for one month and monthly thereafter.

Methotrexate

Off-licence use of methotrexate has been shown to be beneficial for corticosteroid-dependent CSU at a starting dose of 10mg once a week. The evidence is anecdotal and, therefore, this should only be used if all other options have been exhausted[35]

. Where prescribed, the patient would need fortnightly blood monitoring for the first six weeks and then monthly thereafter. Patients would also require a co-prescription of folic acid 5mg once a week on a different day to the methotrexate.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

Case reports have described the successful use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), but this should only be used in specialist centres as a last option[5]

.

The role of the pharmacist in management

Pharmacists are best placed to provide additional support in the identification and management of CSU. They can also refer sub-optimal response to current management strategies to a clinician where appropriate (‘Box 3: Summary of main roles of the pharmacist in chronic spontaneous urticaria’). Ensuring patients with CSU have accurate information about the causes, prognosis and management of their condition is a main way of providing support. A patient information leaflet, for example from the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), could be provided[36]

. Furthermore, a self-management plan could be developed that not only helps patients manage their condition but also reassures them that if current therapy is not effective, there are other treatment options available[36]

.

Box 3. Summary of main roles of the pharmacist in chronic spontaneous urticaria

Primary care:

- Identification of CSU and referral to clinician;

- Identification of poorly controlled CSU and referral of sub-optimal response to therapy to clinician with a suggestion of how to proceed;

- Counselling patients on the causes and prognosis of CSU, inducible factors, self-management, medication, adverse effects and when and how to seek help;

- Ensure patient is counselled on adverse effects and ensure adequate blood monitoring is taking place when patients are prescribed immunosuppressant therapy.

Secondary/tertiary care:

- Ensure prescribing of medications is as per guidelines and NICE recommendations;

- Assess response to therapy with urticaria activity score 7 (UAS7) scores and dermatology QoL index where appropriate;

- Initiation of immunosuppressant therapy at appropriate dose and consideration of any contraindications, including contraceptive status;

- Counselling patients on CSU, medication potential adverse effects and danger symptoms to look out for;

- Blood monitoring and response to therapy;

- Address the psychological impact of CSU and ensure adherence;

- Develop local guidelines for the management of CSU.

Despite national and international guidelines recommending up-titration of antihistamines to four times the licensed dose, many GPs remain reluctant to do so[5]

. There is an urgent need for appropriate and timely treatment escalation for patients failing on first-line therapy and to improve access to specialist care[1]

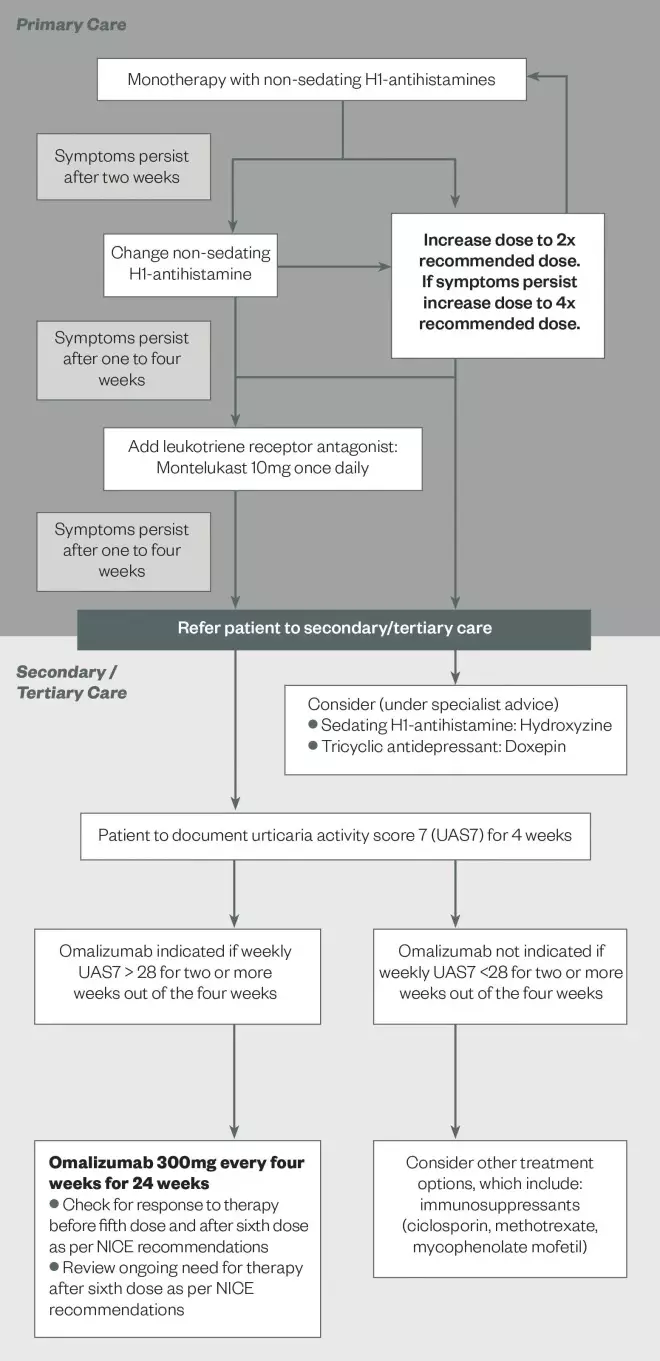

. Pharmacists can raise awareness by developing local guidelines for the management of CSU, to reflect the current best practice. These guidelines would be most helpful for primary care clinicians to diagnose, manage and refer patients to specialist care appropriately. ‘Figure 2: Algorithm for the pharmacological management of CSU’ is an example of a local guideline developed at Barts Health NHS Trust to standardise care across the trust and also to provide local primary healthcare professionals with a reference point for the management of their patients.

Figure 2: Algorithm for the pharmacological management of CSU

Source: Adapted from Barts Health NHS Trust

This algorithm is an example of a local guideline developed by Barts Health NHS Trust to standardise care and to provide local primary healthcare professionals with a reference to guide pharmacological management of CSU.

Marium Naqvi

is specialist respiratory pharmacist at Barts Health NHS Trust (at the time of undertaking this work) and Runa Ali is ‎consultant allergist and respiratory physician at ‎Barts Health NHS Trust. Correspondence to: mnaqvi@nhs.net

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Allergy UK. Wheals of Despair. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: breaking free from the cycle of despair. June 2014.

[2] Sánchez-Borges M, Asero R, Asotegui IJ et al. Diagnosis and treatment of angioedema: a worldwide perspective (position paper). World Allergy Organization Journal 2012;5:125–147. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182758d6c

[3] Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy 2011;66:317-330. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x

[4] Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, mid-2011 and mid-2012. Office of National Statistics. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/population-estimates-for-uk–england-and-wales–scotland-and-northernireland/mid-2011-and-mid-2012/index.html (accessed March 2016).

[5] Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy 2014; doi: 10.1111/all.12313

[6] Gaig P, Olona M, Munoz Lejarazu D et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in Spain. J Invest Allergol Clin Immunol 2004;14:214–220. PMID: 15552715

[7] Zazzali JL, Broder MS, Chang E et al. Cost, utilization, and patterns of medication use associated with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;108:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.10.018

[8] Zuberbier T, Balke M, Worm M et al. Epidemiology of urticaria: a representative cross-sectional population survey. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010;35:869–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03840.x

[9] Furue M, Yamazaki S, Jimbow K et al. Prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan: a nationwide, crosssectional, seasonal, multicentre, hospital-based study. J Dermatol 2011; 38:310–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01209.x

[10] Baiardini I, Giardini A, Pasquali M et al. Quality of life and patients’ satisfaction in chronic urticaria and respiratory allergy. Allergy 2003;58:621–623. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00091.x

[11] Maurer M, Ortonne JP, Zuberbier T. Chronic urticaria: a patient survey on quality-of-life, treatment usage and doctor-patient relation. Allergy 2009;64:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01853.x

[12] O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J et al. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. British Journal of Dermatology 1997;136:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14895.x

[13] Powell RJ, Leech SC, Till S et al. BSACI guideline for the management of chronic urticaria and angioedema. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 2015;45:547–565. doi: 10.1111/cea.12494

[14] Saini SS. Basophil responsiveness to chronic urticaria. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2009;9:286-290. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0040-3

[15] Kaplan AP. Clinical practice. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346:175–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011186

[16] Kang MJ, Kim HS, Kim HO et al. The impact of chronic idiopathic urticaria on quality-of-life in Korean patients. Ann Dermatol 2009;21:226–229. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.226

[17] Bernstein I, Li JT, Bernstein DI et al. Allergy diagnostic testing: an updated practice. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2008:100:Supplement 3. PMID: 18431959

[18] NICE Technology Appraisal 339: Omalizumab for previously treated chronic spontaneous urticaria. September 2015.

[19] Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M et al. Development, validation, and initial results of the angioedema activity score. Allergy 2013;68:1185-1192. doi: 10.1111/all.12209

[20] Both H, Essink-Bot ME, Busschbach J et al. Critical review of generic and dermatology-specific health-related quality of life instruments. J Investig Dermatol 2007;127:2726–2739. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701142

[21] Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Braido F et al. A new tool to evaluate the impact of chronic urticaria on Quality of Life: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL). Allergy 2005;60:1073–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00833.x

[22] Goldsobel AB, Rohr AS, Siegel SC et al. Efficacy of doxepin in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1986;78:867–873. PMID: 3782654

[23] Kozel MM & Sabroe RA. Chronic urticaria: aetiology, management and current and future treatment options. Drugs 2004;64:2515–2536. PMID: 15516152

[24] Sabroe RA, Fiebiger E, Francis DM et al. Classification of anti-FcepsilonRI and anti-IgE autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria and correlation with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110:492–499. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126782

[25] Kikuchi Y & Kaplan AP. A role for C5a in augmenting IgG-dependent histamine release from basophils in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:114–118. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120954

[26] Saini S, Rosen KE, Hsieh HJ et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.010

[27] Summary of Product Characteristics. Xolair 150mg solution for injection. Last updated 24 June 2015. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24912/SPC/Xolair%20150mg%20Solution%20for%20Injection/ (accessed March 2016).

[28] Zhao Z, Ji C, Yu W et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:1742-1750. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1342

[29] Staubach P, Metz M, Chapman-Rothe N et al. Effect of omalizumab on angioedema in H1 -antihistamine resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: results from X-ACT, a randomised controlled trial. Allergy 2016 [in press].

[30] Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M et al. Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013:132;101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.013

[31] Maurer M, Rosén K, Hsie H J et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. New Engl J Med 2013;368:924–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372

[32] Maurer M, Altrichter S, Bieber T et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyreoperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.038

[33] Grattan CEH and Humphreys F on behalf of the British Association of Dermatologists Therapy Guidelines and Audit Subcommittee. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children. British Journal of Dermatology 2007;157:1116–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08283.x

[34] Shahar E, Bergman R, Guttman-Yassky E et al. Treatment of severe chronic idiopathic urticaria with oral mycophenolate mofetil in patients not responding to antihistamines and/or corticosteroids. International Journal of Dermatology 2006;45:1224–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02655.x

[35] Gach JE, Sabroe RA, Greaves MW et al. Methotrexate-responsive chronic idiopathic urticaria: a report of two cases. British Journal of Dermatology 2001;145:340–343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04330.x

[36] British Association of Dermatologists Patient Information Leaflet for Urticaria and Angioedema (June 2015). Available at: http://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=184&itemtype=document (accessed March 2016).

You might also be interested in…

NICE approves twice-yearly infusion that ‘significantly outperforms’ usual treatments for severe lupus

UK Clinical Pharmacy Association launches pharmacogenomics guidance