BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

All patients have the right to refuse to take medicine if they wish to do so, and it is important that this right is recognised[1]

. There may be occasions when patients lack the capacity to take medicines or to understand the consequences of refusing to take medicines. In these circumstances, it may be necessary for healthcare professionals to follow a formal process to allow them to act in the best interests of the patient. The administration of any drug or medical treatment to a patient without their knowledge, in a disguised or deceptive form, is known as covert administration[2]

. Implementation of covert administration requires a complex, multidisciplinary assessment. This article aims to support pharmacy teams and other healthcare professionals in ensuring the appropriate use of covert administration in the care home setting.

Definition

It is understandable that in practice, healthcare professionals may not be acutely aware as to what is and what is not considered covert administration of medicines[3]

. Covert administration is not simply the mixing of a medicine with food or drink to make it more palatable to a patient at their request. By its definition, a medicine is given covertly to a patient in a disguised form without their knowledge but in their best interests[4]

.

Guidance for appropriate use of covert administration is well documented in regulations from the Care Quality Commission (CQC)[5]

, the UK regulator of all health and social care providers, and guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[6]

, England’s health technology assessment body. The CQC states: “When it is agreed to be in a person’s best interests, the arrangements for giving medicines covertly must be in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005”[5]

. In line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005, NICE Guideline SC1 (managing medicines in care homes) states: “Health and social care practitioners should not administer medicines to a resident without their knowledge (covert administration) if the resident has capacity to make decisions about their treatment and care”[6]

. NICE Quality Standard 85 (NICE QS85; medicines management in care homes) further supports this by reinforcing that all adults who live in care homes and have been assessed as lacking capacity must only be administered medicines covertly if a management plan is agreed at a meeting held to discuss the patient’s best interests[2]

.

Box 1: The Mental Capacity Act 2005

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) is a law that applies to all adults aged 16 years and over. The Act is designed to protect and empower individuals who may lack the mental capacity to make their own decisions about the care of treatment they receive.

Source: Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Mental capacity assessments

Before consideration is given to covert administration of medicines to a patient, a mental capacity assessment, in line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005[7]

, must be undertaken. At this stage, it is important to consider if a patient has an active advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) that enables someone aged 18 years and over, while still capable, to refuse specified medical treatment for a time in the future when they may lack the capacity to consent to or refuse that treatment. If the patient has an ADRT, it should be adhered to.

It is important to note that capacity assessments are always “task specific” and an assessment specific to the patient’s refusal of medication should be undertaken[8]

. This is usually completed by an appropriately trained senior carer or nurse involved in the daily administration of medicines to the patient. However, if the outcome of the assessment is not entirely clear, an appropriately trained healthcare professional (e.g. GP or specialist nurse) should be involved. In some circumstances, if the outcome of capacity assessments is unclear, the decision may be referred to the Court of Protection. The Court of Protection is part of HM Courts & Tribunal Service; it is a court that has the power to make decisions for people who lack capacity and is responsible for deciding whether someone has the mental capacity to make a particular decision for themselves[9]

.

In broad terms, a capacity assessment is completed in two stages. First, it must be proven that a patient is unable to make a decision because of an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functions of the mind or brain. If this is the case, a patient will be considered legally to lack mental capacity to make a decision or consent if they are unable to:

- Understand in simple language what the medicine is, its purpose and why it is being prescribed;

- Understand the benefits and risks of the medicine and whether there are any suitable alternatives;

- Understand in broad terms what the consequences of not receiving the proposed medicine will be;

- Retain the information for long enough to make an effective decision or communicate their decision in any way.

If patients cannot demonstrate an understanding of one or more parts of this test, then they do not have the relevant capacity at the time of assessment to make decisions about their medicines[7],[10]

.

Best interests decision

When a patient is proven to lack capacity and is unlikely to regain capacity (i.e. the impairment of, or disturbance in, the functions of the mind or brain are not caused by a temporary or reversible change of mental state), then the process to make a decision may proceed. At this stage, all medicines should be reviewed for clinical need. The NICE QS85 guideline suggests that this clinical medication review may be undertaken by the patient’s GP[2]

. However, an appropriately skilled specialist clinical pharmacist would be just as suitable to complete this comprehensive medication review.

As part of the review, medicines that are not performing a function or contributing to health outcomes should be stopped. Importantly, only medicines essential to a patient’s well-being should be given covertly[11]

.

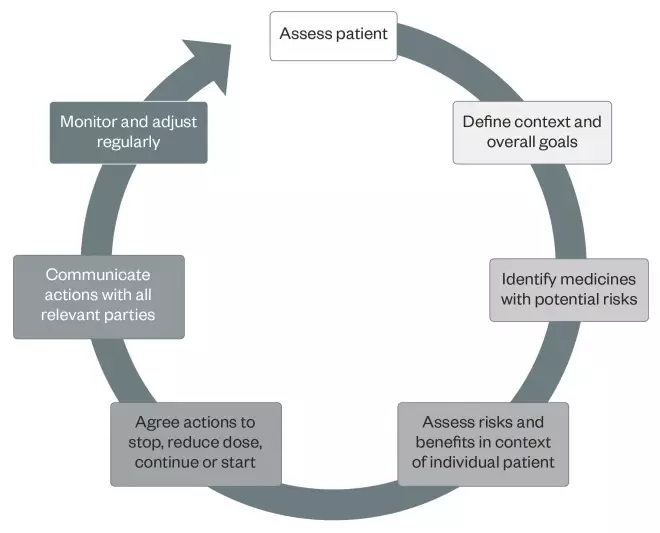

A useful approach to reviewing a patient’s medicines is the patient-centred approach to polypharmacy framework (see ‘Figure 1: Patient-centred approach to polypharmacy summary’[12]

).

Figure 1: Patient-centred approach to polypharmacy summary

Reproduced from Barnett N et al. A patient centred approach to polypharmacy: a process for practice. NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service, 2015

During the review, healthcare professionals should consider how long the patient has been refusing to take their medicines or has been taking their medicines inconsistently, and what the consequences have been. For example, if a patient has not been taking their antihypertensive medication for a fortnight but their recent blood pressure readings are within acceptable parameters, it may be more appropriate to continue without medication and for this decision to be reviewed at defined intervals. This may seem obvious but it is easy to forget to consider how essential a medicine is when trying to manage other considerations, such as formal procedures and whether tablets can be crushed.

Best interests meeting

Once this medication review has been undertaken, a meeting about the patient’s best interests can be held. Attendees at this meeting will usually include the prescriber, a nurse or senior carer from the care home, and a patient representative. If a patient has a nominated power of attorney for health and welfare, this person must be consulted about all treatment decisions. A patient’s next of kin may be invited to this meeting or, if the patient has no representatives who wish to attend, an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) should be invited to represent the patient. IMCAs are a legal safeguard for people who lack the capacity to make specific important decisions (including about where they live and about serious medical treatment options). IMCAs are mainly instructed to represent people when there is no one independent of services, such as a family member or friend, who is able to represent the person (see Social Care Institute for Excellence[13]

for more information).

At this meeting, individuals in attendance will consider the current and future interests of the patient to decide the best course of action. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a checklist that practitioners must follow when making a best interest decision for someone[7],[11],[14]

. The checklist ensures that practitioners involved in making best interest decisions:

- Consider all the relevant circumstances, ensuring that the patient’s age, appearance and behaviour are not influencing the decision;

- Consider delaying the decision if there is a possibility that the person may regain capacity;

- Involve the patient in the decision as much as possible;

- Consider any advance statements made (e.g. ADRT);

- Consider the past and present beliefs and values of the individual, and the patient’s history of decision making;

- Take into account views of family and informal carers, as well as IMCAs or other relevant people;

- Demonstrate that the decision made is the least restrictive alternative or intervention.

The least restrictive option chosen should always give consideration to whether the medicine can be stopped without an adverse effect on the patient’s welfare. After completing the necessary training, pharmacists should advise the multidisciplinary team and patient representatives on the benefits and risks of each medicine for the particular patient. In addition, pharmacists have an important role to play in demonstrating that all other alternative options have been exhausted (e.g. trying to administer the medicines at different times or using a different formulation)[11]

. The patient’s care plan and medical record should document the final decision and how it was made[2]

.

Care plan for covert administration

Once a decision to administer medicines covertly has been made, advice should be sought from a pharmacist about the suitability of each medicine for covert administration. Pharmacists should refer to the summary of product characteristics (SPC) for the medicine or medicines concerned and other appropriate reference sources (see ‘Additional resources for crushing medicines’).

A care plan for administering medicines covertly should be completed. This should explain exactly how medicines should be offered to the patient (i.e. not covertly in the first instance) and then exactly how medicines should be disguised. This care plan, including the need for covert administration, should regularly be reviewed and updated. National guidelines and frameworks do not state a suggested minimal timescale for review, therefore, the period between reviews should consider individual patient factors[2],[6]

.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 includes deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS). DoLS are a set of checks that apply to patients in a hospital or care home, who lack capacity about their care and treatment. They aim to make sure that when care restricts a person’s liberty, with the aim of preventing harm or providing treatment, it is both appropriate and in their best interests. It is the responsibility of care home staff to ensure appropriate DoLS are in place, a process that includes at least two assessments, one by a best interest’s assessor and one by a mental health assessor, usually appointed by the local authority.

Covert administration of medications to a patient may add to a package of care that amounts to a deprivation of their liberty. This is more likely if the medication alters mental state, mood or behaviour, and if it restricts a patient’s freedom.

The Court of Protection recently provided guidance to be followed when providing covert medication to patients subject to a DoLS authorisation[15]

. The principles outlined in the NICE guidance remain the same, but in addition:

- Best interest decision meetings must include the relevant person’s representative (RPR) outlined in the DoLS authorisation. The RPR will usually be a relative or friend of the person who is being deprived of their liberty. If there is no appropriate friend or relative, the RPR will be someone appointed by the supervisory body (e.g. an IMCA);

- If there is no agreement about whether medicines should be given covertly, there should be an application made to the Court of Protection;

- The use of covert medication within a care plan must be clearly identified within the DoLS assessment and authorisation;

- If a standard authorisation of DoLS is granted for a period longer than six months, there should be a clear provision for regular — possibly monthly — reviews of the care plan involving family and healthcare professionals;

- The care home must notify the supervisory body of changes to the covert medication regime, including changes to the nature, strength or dosage of medications being administered covertly. Such changes should always trigger a review of the authorisation;

- If there is an RPR, they should be fully involved in these discussions or reviews, so they can apply to the supervisory body for a review of the DoLS authorisation if appropriate.

Practical considerations for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians

Best practice points for covert administration are included in ‘Box 2: Best practice points for covert administration’. Important practical considerations for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians include:

- If receiving a request for information about crushing or disguising medicines, explore the circumstances behind the original request. It may be unwise to facilitate the covert administration of medication when the formal process has not been followed.

- When giving advice about administration of medicines, be clear to nurses and care staff that administering medicines covertly should be quantifiable. For example, if mixing with yoghurt, it is advisable to mix the medicine with only one or two spoonfuls to ensure the person administering can quantify that the whole dose has been taken[16]

. Furthermore, avoid mixing multiple medicines together if possible[17]

. - There is not much evidence in the literature about crushing medicines or mixing them with food or drinks. However, important considerations include:

- Avoiding administering medicines with food or drink when there are known interactions (e.g. milk with ciprofloxacin, tetracyclines);

- Investigating the patient’s likes, dislikes and daily routines before advising how medicines can be disguised. Just because a medicine can be mixed with orange juice, the patient will not drink it if he or she does not like orange juice;

- There is not always a licensed way to give a medicine covertly to a patient because tablets become unlicensed when crushed and most liquids are not licensed to be mixed with other liquids. All decisions about formulation should be made with regard to the individual patient.

- If you are worried about the absorption or effect being altered and cannot find any information, consider whether the effect of the medicine can be measured (using physical parameters, observations or blood work) and advise that more frequent monitoring may be required. If there is no way to establish the potential effect that the medicine is having, discuss this with the prescriber.

Even if it is disguised, consider the acceptability of the crushed dose form to the patient. For example, crushed sertraline tablets can have a bitter taste and numbing effect that may put a patient off food[3]

.

Box 2: Best practice points for covert administration

Covert administration should be:

- A last resort – only implemented when there is no viable alternative;

- Medicine specific – the need must be identified for each medicine prescribed;

- Time limited – it should be used for as short a time as possible, and the need should be reviewed regularly.

The decision making process should be:

- In the best interests of the patient – due consideration should be given to the holistic impact on the patient’s health and well-being;

- Transparent – it must be easy to follow and clearly documented;

- Inclusive – involving discussion and consultation with appropriate advocates for the patient. It must not be a decision taken alone.

Adapted from PrescQIPP Bulletin 101[11]

Additional resources on crushing medicines:

- British National Formulary for Children may contain information about alternative formulations;

- British National Formulary – local medicines information department

- Medicines Complete – handbook of drug administration via enteral feeding tubes

- NEWT guidelines – for administration of medication to patients with enteral feeding tubes or swallowing difficulties

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Human Rights Act. 1998. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/42/contents (accessed June 2016)

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality Standard 85, statement 6. March 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs85 (accessed August 2016)

[3] UK Medicines Information. What legal and pharmaceutical issues should be considered when administering medicines covertly? UKMi Q&A 365.3. August 2014. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/QA365_3_Covertadminofmedicines.doc (accessed August 2016)

[4] Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. Good practice guide – covert administration. November 2013. Available at: http://www.mwcscot.org.uk/media/140485/covert_medication_finalnov_13.pdf (accessed August 2016)

[5] Care Quality Commission. Regulations for service providers and managers. Regulation 12: safe care and treatment. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/regulations-service-providers-and-managers (accessed August 2016)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Managing Medicines in Care Homes (SC1). March 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1 (accessed August 2016)

[7] Mental Capacity Act 2005. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/1 (accessed June 2016)

[8] British and Irish Legal Information Institute. England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions. Available at: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2013/478.html (accessed August 2016)

[9] Gov.uk. Court of Protection. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/courts-tribunals/court-of-protection (accessed August 2016)

[10] Royal College of General Practitioners. Mental capacity act toolkit for adults in England and Wales 2011. Available at: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/~/media/Files/CIRC/CIRC-76-80/CIRC-Mental-Capacity-Act-Toolkit-2011.ashx (accessed August 2016)

[11] NHS PrescQIPP Bulletin 101. Best practice guidance in covert administration of medication. September 2015. Available at: https://www.prescqipp.info/resources/send/216-care-homes-covert-administration/2147-b101-covert-administration (accessed August 2016)

[12] Barnett N, Oboh L & Smith K. A patient centred approach to polypharmacy: a process for practice. NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2015. Available at: http://wessexahsn.org.uk/img/projects/Patient%20Centred%20Approach%20to%20Polypharmacy%20(summary%20formerly%20seven%20steps)_July%202015%20Vs%202%20(NB)%20(LO)%20(KS).pdf (accessed August 2016)

[13] Social Care Institute for Excellence. Independent Mental Capacity Advocate resources. Available at: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/imca/ (accessed August 2016)

[14] The British Psychological Society. Best interests: guidance on determining the best interests of adults who lack the capacity to make a decision (or decisions) for themselves [England and Wales]. Available at: http://www.mentalhealthcare.org.uk/media/downloads/Best_Interests_Guidance.pdf (accessed August 2016)

[15] Ford G & Tracy J. Covert medication and DOLS – new court guidance. July 2016. Available at: http://www.hempsons.co.uk/news/newsflash-covert-medication-dols-new-court-guidance/ (accessed August 2016)

[16] Smyth J. The NEWT guidelines for administration of medication to patients with enteral feeding tubes or swallowing difficulties. Betsi Cadwaladr University Local Health Board (East). Available at: http://www.newtguidelines.com (accessed June 2016)

[17] Department of Health. Guidance: Mixing of medicines prior to administration in clinical practice: medical and non-medical prescribing. May 2010. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mixing-of-medicines-prior-to-administration-in-clinical-practice-medical-and-non-medical-prescribing (accessed August 2016)