Shutterstock.com

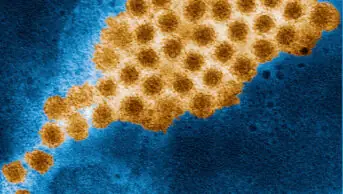

Dengue fever and chikungunya are insect-borne viral diseases that can cause severe morbidity. They are both viral infections spread by the Aedes mosquito — in contrast to the Anopheles mosquito, which is associated with malaria. However, they are caused by different forms of virus: chikungunya is caused by Togaviridae alphavirus, while dengue fever is caused by Flavirideae flavivirus1,2.

Both diseases are endemic in various areas in the tropics and overlap in distribution to a large extent with malaria. The symptoms of the two diseases can make them difficult to distinguish from malaria in the early stages. The risk of dengue fever and chikungunya is highest in tropical areas also associated with malaria. Areas of particular risk include sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Central and South America3–5.

Outbreaks also occur in regions often not associated with mosquito-borne diseases. While not common, locally acquired infection of dengue fever has been known to happen in Europe (e.g. in France, Italy and Spain). In February 2025, two locally acquired cases were reported in Madeira, Portugal3,6.

Cases of chikungunya are rising worldwide. As of September 2025, France reported 301 cases of locally acquired chikungunya, while Italy reported 107 cases4. For more information on the number of worldwide dengue fever and chikungunya cases per 100,000 people, see Figure 14,5.

Dengue fever

Dengue fever is one of the most common viral arthropod-borne diseases in the world. Estimates vary, but one model suggests there could be 390 million infections and around 22,000 associated deaths each year worldwide7. However, the number of infections reported to health organisations is much lower. In 2024, there were more than 14 million dengue fever cases reported globally, which is the highest number on record, alongside an associated 9,508 deaths1. The incidence of dengue fever has increased over the past 50 years, which can be attributed to several factors, including population growth, rural-urban migration, increases in discarded waste that can serve as mosquito breeding grounds (e.g. used tyres that accumulate water) and global spread caused by increased international trade8.

There were 904 confirmed reports of dengue fever in travellers returning to the UK in 2024, compared with 631 reports in 2023. Most cases were linked to travel to Southern and South-Eastern Asia, which could be an underestimate of the actual number of cases9.

Dengue fever is caused by Flavirideae flavivirus for which humans are the chief host. Non-human primates also carry the disease, although cross-infection to humans is probably rare. Human-to-human transfer is via the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes1.

Four different serotypes of Flavirideae flavivirus can cause a dengue fever infection. After infection, the patient is immune to causative serotype but reinfection with another serotype is still possible, which may be associated with more severe complications. Studies on cohorts of travellers have found high rates of sero-prevalence, with a lower incidence of clinical infection10. One meta-analysis, published in 2023, which included 131,953 dengue cases, found that half of individuals have asymptomatic infection11. Other sources estimate that around 80% of people infected are asymptomatic, meaning that 20% might have symptoms, and less than 5% of people have severe disease12.

The incubation period of dengue fever is around 4–7 days, but can range from 3–14 days. As a result, symptoms in travellers that started more than 14 days after return are unlikely to be dengue fever. The initial symptom is fever, which may subside only to recur some days later. This usually lasts 2–7 days, but recovery can take several weeks, accompanied by fatigue and malaise1.

Other symptoms include:

- Severe headache;

- Myalgia;

- Back pain;

- Abdominal tenderness;

- Joint and muscle pain, which can be severe;

- A maculopapular rash, which occurs in 50–80% of cases and usually appears on the trunk, spreading to the limbs and face;

- Minor bleeding from mucous membranes, such as the gums or nose, may be experienced in adults1,12.

Symptoms of dengue fever in children can be milder and are often accompanied by diarrhoea and vomiting; however, children may be more prone to severe complications13.

Dengue fever can affect the mechanisms of blood clotting and patients often develop thrombocytopenia. Although rare, it can also affect the function of other organs, such as the liver and kidneys14.

Severe dengue — previously termed dengue haemorrhagic fever — is a severe and potentially fatal complication characterised by widespread haemorrhage and extravasation of fluid, leading to hypotension and shock and possibly organ damage, including kidney and liver failure15. Dengue shock syndrome is a severe, life-threatening complication of severe dengue. If untreated, the mortality rate is 10-20%16.

Severe dengue is rarely seen in travellers and is more likely to occur in children in endemic areas, particularly those who have had dengue fever previously. This is believed to be because infection by a different dengue serotype results in a greater immunological response, and the various inflammatory mediators produced cause the symptoms of severe dengue17. Travellers making frequent trips to dengue fever areas could be at increased risk of severe dengue, but so few cases have been reported in travellers that this has not been confirmed17.

Chikungunya

Chikungunya was first recognised in the early 1950s in Tanzania. The name means ‘that which bends up’, which is a reference to the bent posture seen as a result of the associated arthritic symptoms2.

Chikungunya is caused by a range of mosquito species. In Asia, it is principally transmitted by Aedes.aegypti, and Aedes.albopictus mosquitoes, which are species found in more temperate climates such as Southern Europe, and are also known to carry the disease. In Africa, a range of species carry the disease, and it exists as an enzootic infection with a reservoir of the disease in primates and small mammals that can be passed to humans2.

In 2025, there has been a global increase in chikungunya cases. Notable outbreaks include the Indian Ocean island La Réunion, which noted 54,410 cases between August 2024 and July 2025, following a previous outbreak in 2005/2006 that affected 266,000 individuals18. Between June and September 2025, the Guangdong province in China has reported over 8,000 cases of chikungunya19.

In the UK, a total of 73 cases of chikungunya were reported between January and June 2025, compared with 27 cases during the same period in 202420.

Chikungunya shares similar characteristics to the symptoms of dengue fever but does not normally cause haemorrhagic complications — although some cases exhibiting haemorrhagic symptoms have been described in Asia. The distribution of the joint involvement and rash can help distinguish it from dengue fever, see Table1,2. Chikungunya has a short incubation period, usually 4–8 days — although this can range from 2–10 days — and can occur while travelling. The initial fever is accompanied by chills, which lasts for 3–4 days before remitting and then reoccurs a few days later. The illness itself lasts for up to two weeks, and recovery can take a further few weeks. Most patients have no further complications, although arthritic symptoms can occur, which can persist for up to a year, while some deaths have been reported among people living in endemic areas2.

Treatment

Patients should be referred to their GP if they present with any symptoms of dengue fever or chikungunya following overseas travel to areas where dengue fever, chikungunya or malaria are endemic. This referral should be urgent if the patient presents with fever or any severe symptoms (e.g. severe abdominal pain, repeated vomiting etc.). Travellers who develop a fever while still in the tropics should seek medical help as soon as possible21,22.

There is no specific treatment for either dengue fever or chikungunya. Treatment for uncomplicated cases is symptomatic, with a focus on rehydration and pain relief21,22.

Rehydration is important in all cases of fever, particularly in hot climates, where patients should be treated with oral rehydration therapy as required. Patients with severe dengue should be treated with parenteral rehydration21,22.

Patients with dengue fever should use paracetamol for analgesia, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided in dengue fever owing to the risk of haemorrhagic complications. Patients with chikungunya who develop arthritic symptoms can be treated with NSAIDs; however, they should be monitored closely as the disease can sometimes cause thrombocytopenia21,22.

Prevention

The Qdenga vaccine (Takeda) is available in the UK for individuals aged four years and over who have previously had dengue fever and are planning to travel to, or are currently in, a high-risk area. The vaccine requires two doses, given three months apart23.

Two new chikungunya vaccines have recently been approved for use in the UK. IXCHIQ (Valneva) was approved in February 2025 and is a live vaccine that can be used in individuals aged 18–59 years. Vimkunya (Bavarian Nordic) was approved in May 2025 and is a virus-like particle vaccine for individuals aged 12 years and over. The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation advises against the use of IXCHIQ in individuals aged over 60 years following reports of 23 cases of serious adverse events in individuals aged 62–89 years who received the vaccine22,24.

Chikungunya vaccination should be considered in those travelling to regions with active outbreaks or in frequent travellers to regions where there has been chikungunya transmission in the past five years22.

The most important measure that a traveller can take against these diseases is the use of bite avoidance measures throughout the day. The Aedes mosquito is referred to as a ‘daytime’ feeder and tends to be more active during the cooler parts of the day, such as early morning and late afternoon1,2.

Covering up exposed skin is important and using insecticide impregnated clothing should be considered. Travellers should be advised to apply a 50% DEET-based repellent to exposed skin. Alternative preparations containing icaridin, lemon eucalyptus and p-menthane-3,8-diol or IR3535 are also effective1,2. For more information, see ‘How to make the most of travel health consultations’.

Conclusion

Dengue fever and chikungunya are viral infections spread by types of mosquito. Both infections have similar symptoms, including fever, malaise and fatigue.

Patients should be referred to their GP if they present with any symptoms of dengue fever or chikungunya following overseas travel to areas where dengue fever, chikungunya or malaria are endemic. This referral should be urgent if the patient presents with fever or any severe symptoms.

There is no specific treatment for either dengue fever or chikungunya, while treatment for uncomplicated cases is symptomatic, with a focus on rehydration and pain relief.

This article has been updated by The Pharmaceutical Journal team and reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in the journal in May 2015.

- 1.Dengue Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue

- 2.Chikungunya Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya

- 3.Dengue worldwide overview. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2025. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue-monthly

- 4.Seasonal surveillance of chikungunya virus disease in the EU/EEA, weekly report. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2025. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya-virus-disease/surveillance-and-updates/seasonal-surveillance#:~:text=Epidemiological%20summary,cases%20of%20chikungunya%20virus%20disease

- 5.Global dengue surveillance. World Health Organization. 2025. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/dengue_global/

- 6.Areas with Risk of Dengue. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areas-with-risk/index.html

- 7.Pourzangiabadi M, Najafi H, Fallah A, Goudarzi A, Pouladi I. Dengue virus: Etiology, epidemiology, pathobiology, and developments in diagnosis and control – A comprehensive review. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2025;127:105710. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2024.105710

- 8.Wilder‐Smith A. Dengue in International Travelers: Quo Vadis? J Travel Med. 2013;20(6):341-343. doi:10.1111/jtm.12063

- 9.Imported dengue cases reach record high. UK Health Security Agency. 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/imported-dengue-cases-reach-record-high

- 10.Ratnam I, Leder K, Black J, Torresi J. Dengue Fever and International Travel. J Travel Med. 2013;20(6):384-393. doi:10.1111/jtm.12052

- 11.Asish PR, Dasgupta S, Rachel G, Bagepally BS, Girish Kumar CP. Global prevalence of asymptomatic dengue infections – a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023;134:292-298. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.07.010

- 12.Factsheet for health professionals about dengue. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2023. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue-fever/facts

- 13.Verhagen LM, de Groot R. Dengue in children. Journal of Infection. 2014;69:S77-S86. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.020

- 14.Castilho BM, Silva MT, Freitas ARR, Fulone I, Lopes LC. Factors associated with thrombocytopenia in patients with dengue fever: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e035120. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035120

- 15.Wang WH, Urbina AN, Chang MR, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever – A systemic literature review of current perspectives on pathogenesis, prevention and control. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2020;53(6):963-978. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.007

- 16.Schaefer T, Panda P, Wolford R. Dengue Fever. StatPearls; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430732/

- 17.Halstead S, Wilder-Smith A. Severe dengue in travellers: pathogenesis, risk and clinical management. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2019;26(7). doi:10.1093/jtm/taz062

- 18.Chikungunya Outbreak Spreads from Indian Ocean Islands, Posing Global Risk. Health Policy Watch. 2025. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/who-warns-of-global-risk-of-mosquito-borne-chikungunya/

- 19.Chikungunya virus in China. Wellcome Sanger Institute. 2025. https://sangerinstitute.blog/2025/08/07/chikungunya-virus-in-china/

- 20.Rise in chikungunya cases in UK travellers returning from abroad. UK Health Security Agency. 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/rise-in-chikungunya-cases-in-uk-travellers-returning-from-abroad

- 21.Dengue . NHS. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dengue/

- 22.Chikungunya. TravelHealthPro. 2025. https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/disease/31/chikungunya

- 23.Qdenga® dengue vaccine guidance. TravelHealthPro. 2024. https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/news/763/qdenga-dengue-vaccine-guidance

- 24.Chikungunya vaccine in UK travellers: JCVI advice. Department of Health and Social Care. 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chikungunya-vaccine-for-uk-travellers-jcvi-advice-16-july-2025/chikungunya-vaccine-in-uk-travellers-jcvi-advice

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control