Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article you should be able to:

- Understand the difference between pre-school wheeze and childhood asthma;

- Recognise the symptoms of pre-school wheeze, and when referral is necessary;

- Understand how lower airway infection and inflammation cause pre-school wheeze;

- Outline the management strategy for maintenance and prevention of pre-school wheeze.

This article was reviewed for accuracy by expert authors in May 2023 and no changes were required.

Lower respiratory tract illnesses with wheeze occur in around one-third of all pre-school children aged 1–5 years. They are among the most common causes of childhood attendances to emergency departments, accounting for almost 75% of all childhood admissions for wheezing in the UK[1]. Although admissions and acute presentations have fallen for school-age children with asthma, rates for pre-school children continue to increase[2].

Current management strategies for acute attacks and maintenance treatment to prevent pre-school wheeze are extrapolated from school-age children with asthma[3]. However, the pathophysiology for acute pre-school wheeze differs from childhood asthma and therefore requires different management[3].

This article focuses on the diagnosis and management of wheezing in pre-school children aged 1–5 years, highlighting the main differences compared with school-age asthma. It is important for pharmacists to understand these differences, as parents or carers will want to understand how treatment differs and discuss concerns regarding potential side effects of medicines.

Diagnosis

Bush et al. define wheeze as “a high-pitched whistling sound usually in expiration and associated with increased work of breathing, but which can sometimes be heard in inspiration”[2]. It is associated with lower airway obstruction[4].

It is essential that healthcare professionals assess a child when acutely symptomatic to ensure the main presentation is with true wheeze and not any other upper airway respiratory noise. Relying only on parental reports of symptoms can be misleading, and may result in stridor (a high-pitched noise resulting from turbulent airflow through a partially obstructed upper airway), or other upper airway noises being mistaken for wheezing[5,6]. If the wheeze cannot be confirmed on auscultation (i.e. listening to the internal sounds of the body, usually using a stethoscope), an accurate description of the symptoms from the parent or carer is essential, and should be accompanied by objective evidence from video or sound recordings where possible[7].

A thorough history and physical examination should be conducted to exclude chronic suppurative lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease of prematurity (bronchopulmonary dysplasia), congenital airway abnormalities, gastro-oesophageal reflux or foreign body aspiration.

There are some important questions pharmacists can ask parents or carers during consultations:

- Does your child have noisy breathing?

- Does the noise sound like a high-pitched whistle? (Consistent with wheeze);

- Does the noise sound like a snore or rattle in the chest? (Suggests an upper airway noise, not wheeze);

- Is there associated difficulty in breathing/breathlessness and/or cough? (Consistent with wheeze);

- Do they cough, choke or gag when eating or drinking? (Suggests aspiration);

- If they cough, does it sound chesty, like a smoker’s cough? (Suggests chronic suppurative lung disease);

- Do they have noisy breathing or breathlessness only with colds? (Consistent with wheeze);

- Does the noisy breathing/difficulty in breathing get worse with physical activity? (Consistent with wheeze)[2][8].

Red flags in the history that should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses include:

- Symptoms present from birth or in the neonatal period;

- Persistent wet or productive cough;

- Family history of respiratory conditions;

- Failure to thrive;

- Digital clubbing;

- Nasal polyps;

- Excessive vomiting or posseting;

- Continued symptoms and acute presentations, despite being prescribed high-dose maintenance inhaled corticosteroids (>400 micrograms beclometasone per day equivalent), or being prescribed frequent courses of oral steroids[2].

Pre-school children with any of these features should be referred to their prescriber, and onwards to a specialist clinic for further investigations, as a simple diagnosis of pre-school wheeze is unlikely.

Causes of pre-school wheeze

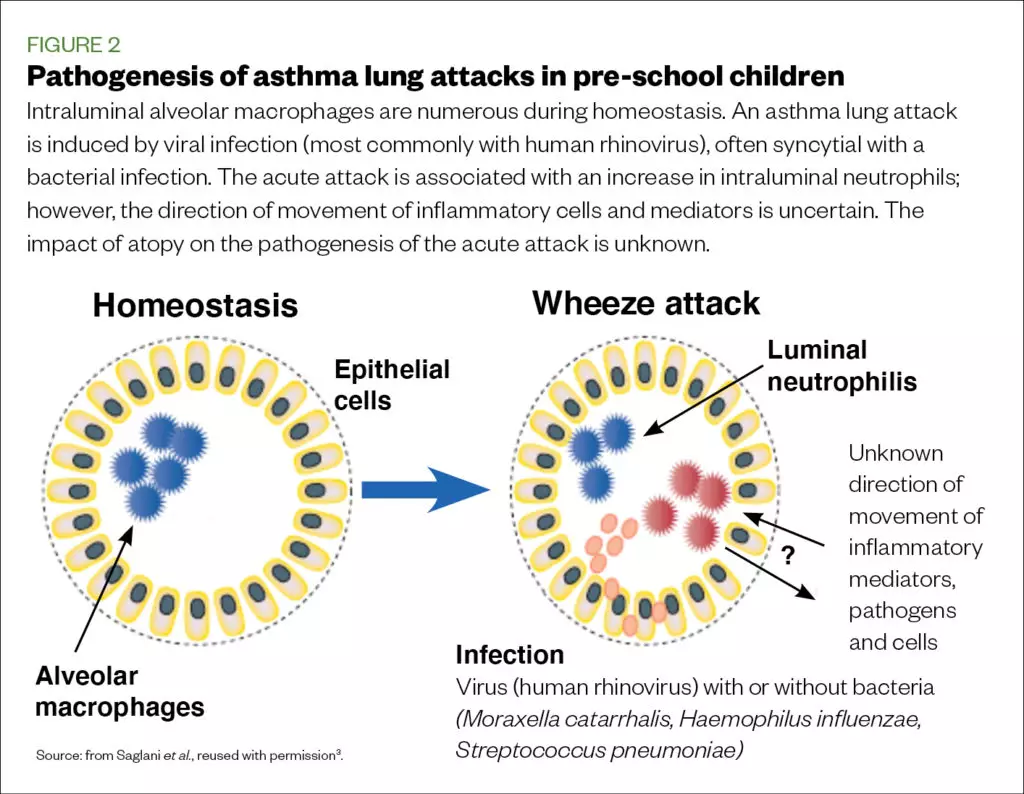

Lower airway infection

Acute wheeze in pre-school children is predominantly caused by viral respiratory infections, including rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)[3]. Rhinovirus A and C are more pronounced in acute attacks and rhinovirus C is associated with more severe attacks[9].

Bacterial pathogens, including Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, may also be associated with acute wheezing episodes in pre-school children[10]. The Copenhagen prospective study on asthma in childhood followed 411 children — aged between 4 weeks and 3 years — in Copenhagen, and found a significant correlation with infection of these three bacteria[10]. Robinson et al. studied 35 pre-school children with wheeze (median age 36 months) and suggested airway bacterial dysbiosis as a possible explanation for the severe and recurrent attacks experienced by some pre-school children[11]. Although this bacterial presence is understood, the role of targeted antibiotic therapy in preventing acute episodes of wheeze remains unclear.

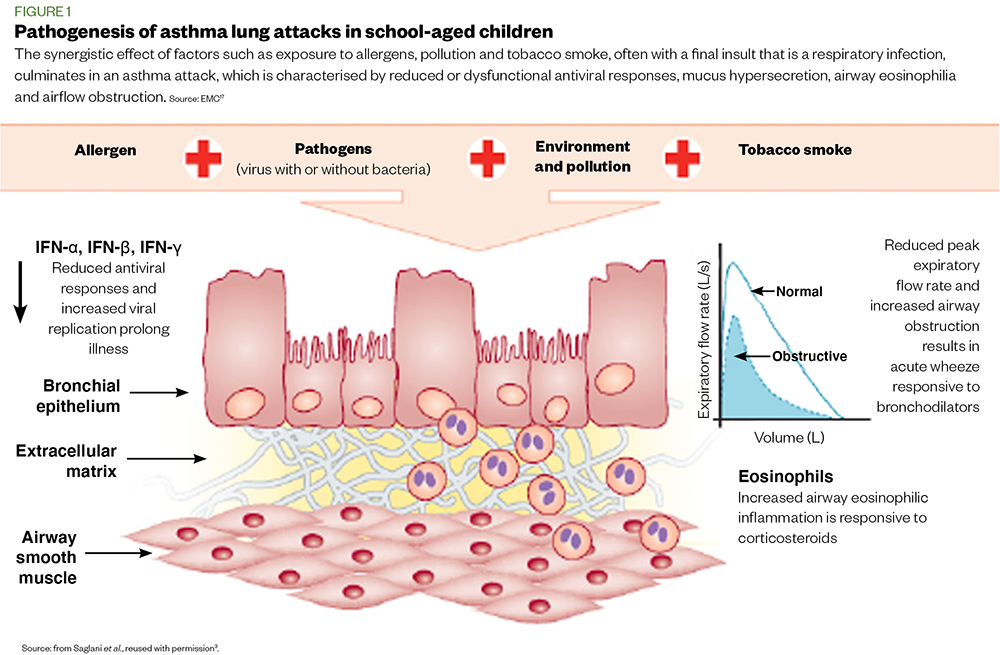

Lower airway inflammation

Allergen sensitisation (e.g. to pollen, house dust mites, smoking) is present in most school-age children with associated eosinophilic airway inflammation, which is exacerbated during acute attacks, even when the attacks are caused by respiratory viruses[12]. Therefore, corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment owing to their efficacy in reducing airway eosinophilia in school-age children. In contrast, around 75% of children with pre-school wheeze are non-atopic (i.e. not sensitised to allergens, and therefore airway eosinophilia is not common)[11]. During stable disease (between acute attacks), there is evidence that a sub-group of children with pre-school wheeze with sensitisation to aero-allergens, and who have elevated blood eosinophils, are likely to have lower airway eosinophils[13][14]. Therefore, these children may respond to maintenance inhaled steroids to prevent attacks.

However, the sub-group of children with pre-school wheeze and without aero-allergen sensitisation are likely to have predominant lower airway neutrophilia, and are refractory to maintenance inhaled corticosteroids[13]. It is likely that the significant influence of respiratory infections in driving attacks of pre-school wheeze, and presence of bacterial infection, even during stable disease, are driving neutrophilia in non-allergic patients, but at present, biomarkers that can identify children with neutrophilic phenotype are lacking. The pathogenesis of asthma lung attacks in school-age children can be seen in figure 1, and that in pre-school children can be seen in figure 2[3].

Management

Once a diagnosis of wheezing has been confirmed, management options for acute attacks and maintenance therapy to prevent attacks in pre-school children with recurrent wheezing should be considered separately. If a patient presents in the community or general practice pharmacy setting with an acute attack, pharmacy teams should ask the patient’s parent/carer to follow their personalised wheeze plan and call emergency services[15].

Management of acute attack

This is usually undertaken in a hospital setting, with the main aim of stabilising respiratory function.

The pharmacist’s responsibility in this setting includes ensuring that all medication, especially the type of inhaler (device) with a spacer, is prescribed correctly. They must also ensure patients are discharged from hospital with appropriate medication, and that parents/carers have been shown how to use the inhaled therapy correctly. If the medication is new to the patient, a referral can be made to the community pharmacist for follow-up through the national Transfers of Care Around Medicines (TCAM), using PharmOutcomes or the new medicines service[16–18]. Respiratory pharmacists embedded in the asthma service may wish to follow up with patients discharged from hospital in their virtual clinic to ensure transitional care is seamless.

Oxygen

The primary treatment of an acute attack is to treat hypoxia with oxygen therapy to maintain oxygen saturation >94%[19].

Bronchodilators

In the absence of hypoxia, short-acting beta2 agonists and/or ipratropium bromide should be initiated using a metered dose inhaler (MDI) and spacer (with mask when appropriate), as per the British Thoracic Society guidelines. Nebulised short-acting beta2 agonists and ipratropium bromide with oxygen should be initiated in children with hypoxia[19].

Bronchodilator therapy should be continued, as required, until wheeze improves.

Magnesium sulphate

If there is a poor response to short-acting beta2 agonists, or a clinical deterioration (e.g. oxygen saturation <92%; respiratory rate >40/min; or the patient is too breathless to talk or feed, though this definition varies between trusts), or based on the clinician’s decision, intravenous magnesium sulphate can be used[20].

Corticosteroids

Most acute attacks of wheezing in pre-school children are in non-allergic children, and are primarily driven by respiratory infection; therefore, these children are very unlikely to have elevated lower airway eosinophils, which would respond to corticosteroids, during acute episodes[3].

Oral corticosteroids (OCS) are often overused, and should only be considered for use in children with acute pre-school wheeze when they are:

- Hypoxic;

- Experiencing a severe attack requiring high dependency unit care[15],[21].

Inappropriate use of OCS in this age group will result in frequent courses, especially during the autumn and winter months, and cause significant harm (e.g. susceptibility to non-tuberculosis infections and pneumonia) and adverse effects (e.g. growth retardation) without clinical benefit[19,22,23].

Antibiotics

The role of antibiotics for the management of acute pre-school wheeze, specifically the macrolide, azithromycin, has been reported in three randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trials[24–26].

In the first trial, 607 children (aged 1–6 years) were randomised to a 5-day course of azithromycin 12mg/kg/daily, or a placebo, over 12–18 months[24]. Of these children, 443 had at least one wheeze attack. Azithromycin significantly reduced the need for oral corticosteroids compared with placebo (P=0.04), the primary outcome measure. No adverse effects or bacterial resistance were observed.

In the second study, 72 children (aged 1–3 years) were treated with a three-day course of azithromycin 10mg/kg/daily or placebo[25]. The median duration of symptoms was reduced from 7.7 days for placebo to 3.4 days for azithromycin. No adverse effects were observed and bacterial resistance was not studied.

The third study involved 300 children (aged 1–5 years) randomised to azithromycin 10mg/kg on day one and 5mg/kg/daily for four further days compared with placebo[26]. There was no reduction in symptoms or time to acute attack between the two groups. Overall, a recent systematic review by Pincheira et al. showed little evidence of benefit of macrolide antibiotics in the treatment of acute pre-school wheeze[27].

Prevention of acute attacks

Traditional approaches to prevention of attacks are based on the clinical phenotype and symptom pattern of the child. The European Respiratory Society taskforce has suggested classification of pre-school wheeze into two main phenotypes:

- Episodic viral wheeze (EVW) is defined as wheeze that occurs only during acute (mainly viral) episodes and is absent between episodes;

- Multiple trigger wheeze (MTW) is defined as wheeze that occurs during episodes as well as between[21].

Recommended treatment for children with EVW is bronchodilators alone (short-acting beta2 agonists and/or ipratropium bromide) as required[3]. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not used for maintenance therapy. Children with MTW should be prescribed maintenance ICS with bronchodilators (short-acting beta2 agonists and/or ipratropium bromide) as required[3,21].

However, this approach has several limitations. The distinction between EVW and MTW changes within patients over time, and there is a large overlap between the two phenotypes[3,21]. The frequency and severity of wheezing episodes should be considered. In view of these limitations, the approach to choosing maintenance therapy is changing.

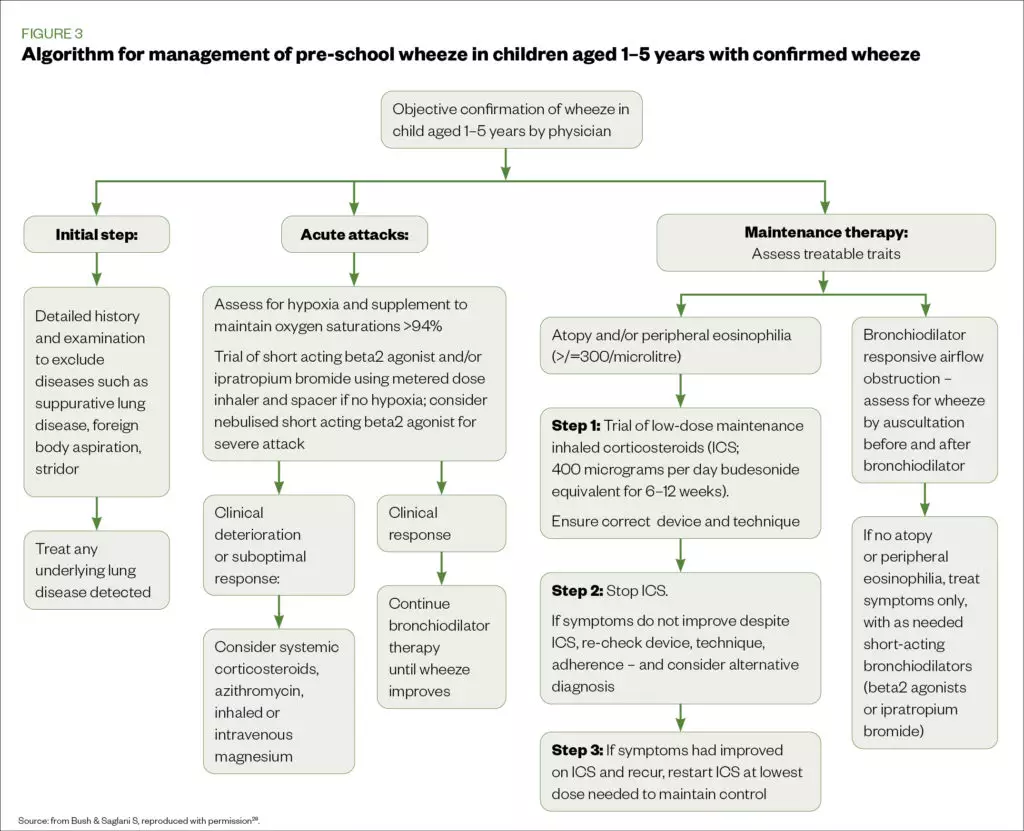

When to use maintenance inhaled corticosteroids

A more practical and evidence-based approach, which makes use of objective biomarkers that identify children most likely to have airway eosinophilia and respond to maintenance ICS, is necessary:

- For pre-school children with no aero-allergen sensitisation (confirmed with blood or skin prick tests) or peripheral blood eosinophil count <300/microlitre (when they are stable and in between episodes), treat symptoms, when present, only with bronchodilators (short acting beta2 agonists and/or ipratropium bromide) as required.

- For those with aero-allergen sensitisation, and/or peripheral eosinophil count of ≥300/microlitre or very severe symptoms, a three-step approach has been recommended (see Figure 3)[27,28].

The following stepwise approach can be adopted to avoid inappropriate use of ICS:

- Step 1: Trial ICS with beclometasone dipropionate (BDP) equivalent 200 micrograms twice daily for 6–12 weeks then review. Ensure advice has been provided on correct technique and appropriate spacer device.

- Step 2: Stop ICS. If symptoms have not improved, check adherence and recheck technique and device. If symptoms have improved, wait to see if they return after stopping ICS.

- Step 3: If symptoms had improved on ICS and return, restart ICS at the lowest effective dose[28].

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Montelukast and other leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are often ineffective in preventing wheeze attacks in pre-school children, and may be associated with neuropsychiatric side effects[29]. They may be trialled in children whose parents are reluctant to use ICS; however, parents must be made aware of nightmares and behavioural changes, which, if present, should prompt the cessation of treatment[30].

Best practice

Pharmacists should note that pre-school children with wheeze are a heterogeneous group and do not all respond to maintenance ICS or LTRA[31,32]. Using ICS or LTRA indiscriminately, without any objective tests or biomarkers, shows no reduction in attacks over the course of a year[31]. In contrast, use of biomarkers to identify children who are likely to have airway eosinophilia shows a significant reduction in attacks with maintenance ICS[32].

Pharmacists should provide advice and guidance on basic aspects of management of children with pre-school wheeze, including:

- Wheeze management plan — where possible, establish that parents have an accurate plan for treating acute attacks and maintenance therapy as appropriate and that it is being followed. Generic asthma plans for pre-school children that could be adapted for wheeze are available from the Asthma UK website[15].

- Inhaler technique — where an opportunity arises, assess and ensure the inhaler technique is correct using the seven-step approach developed by the UK Inhaler Group, and that the right spacer device is used with the correct mask[33,34]. Children aged four years and over should be switched from a spacer with mask to a mouthpiece as soon as they are able to. Poor face seal with a mask will lead to impaired or variable dosage delivery, further reducing drug delivery into the lungs[35]. Limited inhaler devices are used in pre-school children; only an MDI with a spacer can be used effectively[36]. Refer parents to the Asthma UK, RightBreathe and Beat Asthma UK websites[37–39].

- Adherence — an assessment of the number of prescriptions of medication collected over a given time period can serve as a crude check of adherence, particularly the collection of short-acting beta agonists. Collection of more than 12 inhalers per year should be highlighted to the GP and discussed with the parents. An electronic monitoring device (EMD), is the best method for accurate and objective adherence monitoring to ICS therapy[40,41]. In the pre-school age group, objective assessments of adherence may also be helpful in identifying children who are steroid responsive[42]. However, EMDs are not easily available, especially in a primary care setting[40].

- Smoking cessation for parents — in all cases, advice should be provided on smoking cessation, including NHS services and ways to minimise exposure to the child, such as avoiding smoking around the child and in the house, as it is an established risk factor for wheezing[43,44].

- Flu vaccination — encourage and provide advice on the uptake of the flu vaccine.

About the authors

Sukeshi Makhecha is a lead paediatric pharmacist at the Royal Brompton Hospital and a specialist respiratory pharmacist at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital. Sejal Saglani is a professor at the National Heart & Lung Institute at Imperial College London and consultant in paediatric respiratory medicines at the Royal Brompton Hospital.

- 1National Paediatric Asthma Audit Summary Report. British Thoracic Society. 2015.https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-improvement/audit-reports/paediatric-asthma-2015/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 2Bush A, Grigg J, Saglani S. Managing wheeze in preschool children. BMJ 2014;:g15–g15. doi:10.1136/bmj.g15

- 3Saglani S, Fleming L, Sonnappa S, et al. Advances in the aetiology, management, and prevention of acute asthma attacks in children. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2019;:354–64. doi:10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30025-2

- 4Elenius V, Chawes B, Malmberg PL, et al. Lung function testing and inflammation markers for wheezing preschool children: A systematic review for the EAACI Clinical Practice Recommendations on Diagnostics of Preschool Wheeze. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Published Online First: 27 December 2020. doi:10.1111/pai.13418

- 5Majumdar S, Bateman NJ, Bull PD. Paediatric stridor. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Education and Practice 2006;:ep101–5. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.066902

- 6Beigelman A, Bacharier LB. Management of Preschool Children with Recurrent Wheezing: Lessons from the NHLBI’s Asthma Research Networks. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2016;:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.10.003

- 7Saglani S. A video questionnaire identifies upper airway abnormalities in preschool children with reported wheeze. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2005;:961–4. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.071134

- 8Khetan R, Hurley M, Neduvamkunnil A, et al. Fifteen-minute consultation: An evidence-based approach to the child with preschool wheeze. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2017;:7–14. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-311254

- 9Cox DW, Khoo S-K, Zhang G, et al. Rhinovirus is the most common virus and rhinovirus-C is the most common species in paediatric intensive care respiratory admissions. Eur Respir J 2018;:1800207. doi:10.1183/13993003.00207-2018

- 10Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Bonnelykke K, et al. Association of bacteria and viruses with wheezy episodes in young children: prospective birth cohort study. BMJ 2010;:c4978–c4978. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4978

- 11Robinson PFM, Pattaroni C, Cook J, et al. Lower airway microbiota associates with inflammatory phenotype in severe preschool wheeze. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019;:1607-1610.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.985

- 12Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, et al. Asthma. The Lancet 2018;:783–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33311-1

- 13Guiddir T, Saint-Pierre P, Purenne-Denis E, et al. Neutrophilic Steroid-Refractory Recurrent Wheeze and Eosinophilic Steroid-Refractory Asthma in Children. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2017;:1351-1361.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.003

- 14Jochmann A, Artusio L, Robson K, et al. Infection and inflammation in induced sputum from preschool children with chronic airways diseases. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015;:778–86. doi:10.1002/ppul.23366

- 15Cough and wheeze. Asthma UK. . https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/child/manage/cough-and-wheeze/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 16Transfers of Care Around Medicines (TCAM). Community pharmacist support for patients leaving hospital. The AHSNNetwork. 2019.https://www.ahsnnetwork.com/about-academic-health-science-networks/national-programmes-priorities/transfers-care-around-medicines-tcam (accessed Jan 2021).

- 17Pharmoutcomes. Pharmoutcomes. http://www.pharmoutcomes.org/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 18New Medicines Service. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 19Updated BTS/SIGN national Guideline on the management of asthma. British Thoracic Society. 2019.https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/about-us/pressmedia/2019/btssign-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma-2019/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 20Powell C, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Lowe J, et al. Magnesium sulphate in acute severe asthma in children (MAGNETIC): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2013;:301–8. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(13)70037-7

- 21Brand PLP, Caudri D, Eber E, et al. Classification and pharmacological treatment of preschool wheezing: changes since 2008. European Respiratory Journal 2014;:1172–7. doi:10.1183/09031936.00199913

- 22Brode SK, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, et al. The risk of mycobacterial infections associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. Eur Respir J 2017;:1700037. doi:10.1183/13993003.00037-2017

- 23Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al. Oral Prednisolone for Preschool Children with Acute Virus-Induced Wheezing. N Engl J Med 2009;:329–38. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0804897

- 24Stokholm J, Chawes BL, Vissing NH, et al. Azithromycin for episodes with asthma-like symptoms in young children aged 1–3 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2016;:19–26. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00500-7

- 25Bacharier LB, Guilbert TW, Mauger DT, et al. Early Administration of Azithromycin and Prevention of Severe Lower Respiratory Tract Illnesses in Preschool Children With a History of Such Illnesses. JAMA 2015;:2034. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13896

- 26Mandhane PJ, Paredes Zambrano de Silbernagel P, Aung YN, et al. Treatment of preschool children presenting to the emergency department with wheeze with azithromycin: A placebo-controlled randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2017;:e0182411. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182411

- 27Pincheira MA, Bacharier LB, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Efficacy of Macrolides on Acute Asthma or Wheezing Exacerbations in Children with Recurrent Wheezing: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatr Drugs 2020;:217–28. doi:10.1007/s40272-019-00371-5

- 28Bush A, Saglani S. Medical algorithm: Diagnosis and treatment of preschool asthma. Allergy 2020;:2711–2. doi:10.1111/all.14172

- 29Castro-Rodriguez JA, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Ducharme FM. Daily inhaled corticosteroids or montelukast for preschoolers with asthma or recurrent wheezing: A systematic review. Pediatr Pulmonol 2018;:1670–7. doi:10.1002/ppul.24176

- 30Yilmaz Bayer O, Turktas I, Ertoy Karagol HI, et al. Neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions induced by montelukast impair the quality of life in children with asthma. Journal of Asthma 2020;:1–14. doi:10.1080/02770903.2020.1861626

- 31Grigg J, Nibber A, Paton JY, et al. Matched cohort study of therapeutic strategies to prevent preschool wheezing/asthma attacks. JAA 2018;:309–21. doi:10.2147/jaa.s178531

- 32Fitzpatrick AM, Jackson DJ, Mauger DT, et al. Individualized therapy for persistent asthma in young children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016;:1608-1618.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.028

- 33Scullion J, Fletcher M, Murphy A et al. Inhaler Standards and Competency. UK Inhaler Group. https://www.ukinhalergroup.co.uk/uploads/s4vjR3GZ/InhalerStandardsMASTER.docx2019V10final.pdf (accessed Jan 2021).

- 34How to help patients optimise their inhaler technique. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2016. doi:10.1211/pj.2016.20201442

- 35Vincken W, Levy ML, Scullion J, et al. Spacer devices for inhaled therapy: why use them, and how? ERJ Open Res 2018;:00065–2018. doi:10.1183/23120541.00065-2018

- 36Morton RW, Elphick HE, Craven V, et al. Aerosol Therapy in Asthma–Why We Are Failing Our Patients and How We Can Do Better. Front Pediatr Published Online First: 11 June 2020. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.00305

- 37How to use your inhaler. Asthma UK . https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 38Right Breathe website. Right Breathe website. https://www.rightbreathe.com/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 39General Resources. 39. Beat Asthma UK. https://www.beatasthma.co.uk/resources/primary-healthcare-professionals/chronic-management/ (accessed Jan 2021).

- 40Chan AHY, Stewart AW, Harrison J, et al. The effect of an electronic monitoring device with audiovisual reminder function on adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and school attendance in children with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2015;:210–9. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00008-9

- 41Makhecha S, Chan A, Pearce C, et al. Novel electronic adherence monitoring devices in children with asthma: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open Resp Res 2020;:e000589. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000589

- 42Bingham Y, Sanghani N, Cook J, et al. Electronic adherence monitoring identifies severe preschool wheezers who are steroid responsive. Pediatric Pulmonology 2020;:2254–60. doi:10.1002/ppul.24943

- 43Gautier C, Charpin D. Environmental triggers and avoidance in the management of asthma. JAA 2017;:47–56. doi:10.2147/jaa.s121276

- 44Castro-Rodriguez JA, Forno E, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, et al. Risk and Protective Factors for Childhood Asthma: What Is the Evidence? The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2016;:1111–22. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.05.003