This content was published in 2009. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

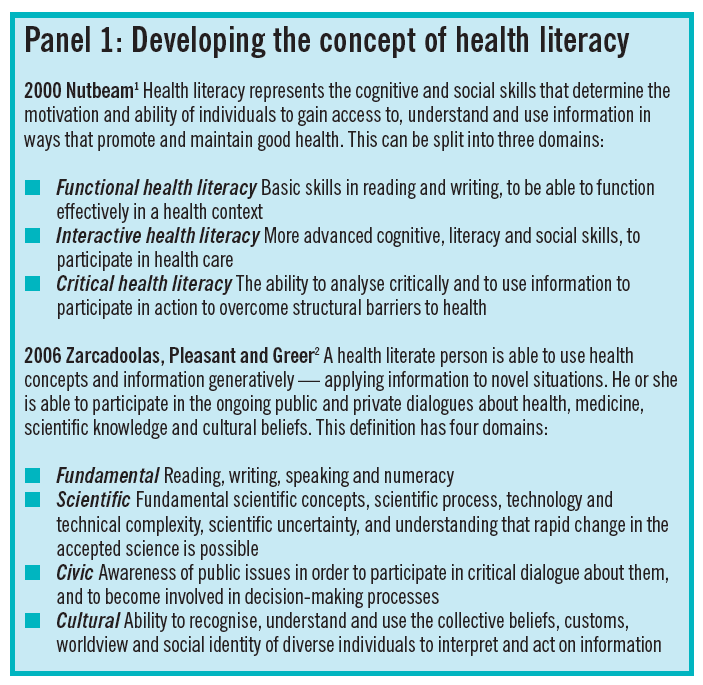

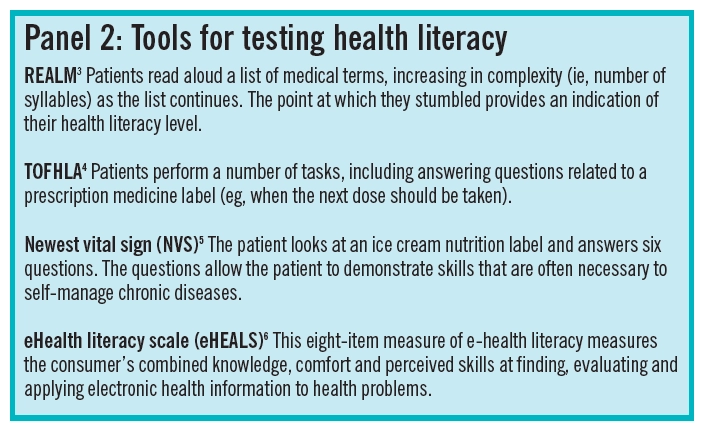

What does the term “health literacy” conjure in your mind? Literacy, no doubt, suggests the ability to read and write. Add health, and it seems straightforward: the ability to read and write in a health context. The concept of health literacy certainly includes an individual’s capacity to access, understand and use written health information but, over the past 20 years, it has widened into something much more interesting and relevant to pharmacy practice. The academic discussion seems to have produced two watersheds, depicted in Panel 1. Before 2000, the research into health literacy concentrated on functional aspects — the reading and writing skills of people who had long term health problems (and who were usually in hospital). In the US, there was a burst of development of tools for testing health literacy, the two most well-known being Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM)[3] and Test of functional health literacy in adults (TOFHLA[4]; see Panel 2).

Donald Nutbeam, former head of public health at the Department of Health, England, extended a narrow, functional view of health literacy into a concept that also has critical and interactive com ponents[1].’ Critical health literacy reflects a capacity to question information before assimilating or rejecting it, and interactive health literacy reflects a capacity to extract information from a range of sources, including social encounters, and to derive meaning that can applied in new situations.

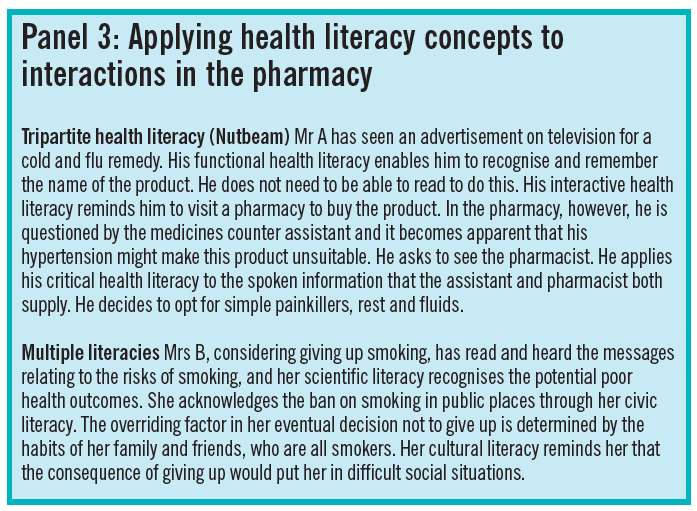

The second watershed is, perhaps, best illustrated by the work of Zarcadoolas et al. This involved the acceptance of multiple literacies: fundamental, scientific, cultural and civic[2].’ They argue that any health-related decision will draw on combinations of these. Examples of a possible pharmacy health literacy dilemma related to each of these interpretations of health literacy are described in Panel 3. More recently, Nutbeam has reflected on health literacy as either a risk or an asset,’ resulting from parallel evolution of the term in clinical care and public health. Both concepts are important in pharmacy practice.

Health literacy policies

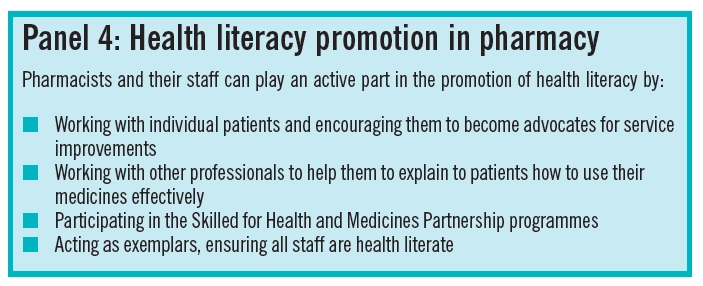

“Choosing health through pharmacy”, a programme for pharmaceutical public health from 2005 to 2015, advocated the promotion of health literacy in community pharmacies and is quite sophisticated regarding the different ways in which health literacy promotion can take place (see Panel 4).

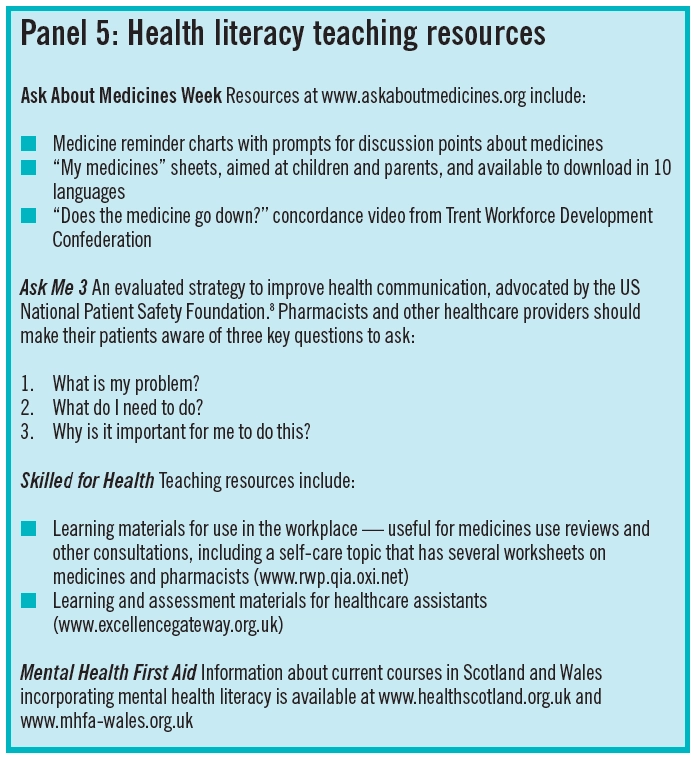

In England, health literacy is a key component of the DoH health inequalities strategy, “Health inequalities: progress and next steps”. This outlines the Government’s approach to hit the 2010 health inequalities public service agreement targets, assessing what has and has not worked, and sets the direction of travel beyond 2010. One of the successes has been the Skilled for Health programme. This is a partnership programme between the DoH, the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills (DIUS), and the learning charity Contin You. It combines learning objectives with health content to help adult learners gain a better understanding of their own health and how to make better use of the NHS, while improving their basic skills (see Panel 5). In Scotland and Wales, mental health is the focus of health literacy policy. A programme of mental health literacy has been developed by NHS Health Scotland, in collaboration with others. The Mental Health Promotion Action Plan in Wales includes mental health literacy initiatives for adults.

Effect on health outcomes

Estimates of the level of low health literacy in the UK have ranged from 11 to 19 per cent, depending on the tool used, geographical region and study set ting. It is argued that patients in a hospital setting have a lower ability to understand healthcare messages. Most health literacy research has taken place outside the UK, but a fairly recent study suggests that over half of England’s adult population have literacy skills below the level needed to discuss a condition interactively with a doctor or specialist.’ In addition, only one quarter were able to calculate body mass index with a formula or identify food groups needed for a balanced diet. Low health literacy is associated with poor health outcomes and each incremental increase towards higher health literacy is associated with a greater likelihood of eating at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day or being a non-smoker.

Let us reflect on the experiences of the two pharmacy customers in Panel 3. Mr A used different health literacy skills to minimise risk to himself, consistent with biomedical evidence and good pharmacy practice. He demonstrated good health literacy skills, despite obtaining all his information from spoken sources (television voiceover and pharmacy staff). Mrs B chose a path not consistent with NHS targets (ie, not giving up smoking) and no doubt frustrated the pharmacist running the smoking cessation clinic. Her health literacy skills, however, were demonstrated in conversation with the pharmacist through her recognition and acknowledgement of the multiple literacies that she drew on to make her decision. This highlights a difficult truth relevant to pharmacy practice: high health literacy is not necessarily related to action that is consistent with health policy and biomedical evidence. By increasing the critical health literacy of individuals we might promote greater independence of thought that brings all the different influences on their health into play. This should be borne in mind when reading policies about health literacy. Pharmacists will be well aware that sometimes it is better to respect the individual’s decision, whether it matches their own aspirations for him or her, or not, in order to maintain a trusting relationship that will be vital for important future decisions.

Medicines use and reasonable adjustments

The recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance on medicines adherence does not contain any references to health literacy, but the safe and effective use of medicines is, undoubtedly, dependent on the capacity to access, understand and use medicines information. The use of oral contraception is a good example of health literacy demands placed on users. The instructions for oral contraception are complex and the information shared at the first prescribing and dispensing can be crucial to a woman’s future risk of pregnancy. A combination of spoken information and a written patient information leaflet are the usual tools: functional and interactive health literacy come into play. Add to this the scientific literacy needed at intervals to sift through the latest media scare about the products, and the cultural literacy to understand the impact that a prescription for the contraceptive pill might have on others’ perceptions of one’s sexual activity, and the demands multiply. The opportunity for giving information and encouraging questions that address some of these literacies could be important during events such as first prescriptions, medicines use review and discharge counselling.

An important area of health literacy research for practice is the stigma associated with poor health literacy. Health professionals are trained to minimise embarrassment in their patients about a number of sensitive issues so why are so many reluctant to broach the subject of literacy? The health literacy differential in the health professional patient relationship seems absolute and inescapable: to become a pharmacist or doctor in our traditional educational system, a student must have the capacity to read, write and assimilate information to a high level. Patients are well aware of this.

The health literacy tests previously cited are useful for population research and policy, to give context and to track how health literacy changes in populations over time. It is less clear whether they are really useful for determining whether an individual patient has adequate health literacy levels to take his or her medicines safely and effectively, or to adopt health promoting activities.

The link between general literacy and heath literacy is complex and it is not possible to assume competency or otherwise. A PhD-educated individual might have poor health literacy, despite high general literacy, if they have never need to engage with the health system. Conversely, a low-income mother who did not complete secondary education might have higher health literacy, despite poor general literacy, because she has learnt to navigate the health system to help her children. For these reasons, the most positive way forward for pharmacy might be to adopt an approach similar to disability policy — that of reasonable adjustments. In essence, pharmacy staff should engage in activities that do not create barriers to services for those with poor health literacy, and that benefit everyone without having to single anyone out for special help.

Health literacy in pharmacy

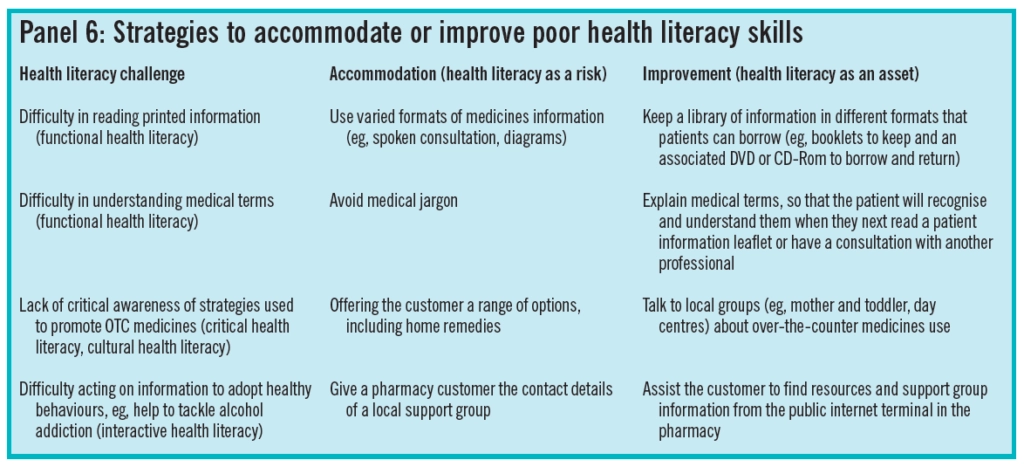

There are two approaches, not mutually exclusive, that recognise variation in the public’s health literacy: to accommodate poor health literacy and to seek to improve it (see Panel 6).

These reflect Nutbeam’s understanding of health literacy as a risk or an asset. The differences in these strategies might seem subtle, but they are profound. Where there is an opportunity to share a skill that the patient can transfer to a future health information query, it should be taken.

So many professional resources, such as the British National Formulary and research journals, are now open to patients that there are excellent opportunities to share literacy skills to promote self-care. Tools that could be used in pharmacies to improve health literacy skills are listed in Panel 5. Some, such as Ask About Medicines Week materials, may already form part of a pharmacist’s toolkit for advising and informing as they discuss medicines with patients. Other, such as the Skilled for Health resources for self-care, may be less familiar but can develop the pharmacists as a teacher.

The evolving concept of health literacy means it is wider than an individual’s capacity. It now includes encounters with health professionals and roles in communities. Pharmacists and staff could reflect, together, on their own perception of what health literacy means and the different ways in which they gather their own health information — we are all subject to the same influences. The Skilled for Health initiative has a set of learning tools and assessment devised for healthcare assistants working in a variety of health contexts. Why not set pharmacy staff a challenge (how health literate are we?) and encourage them to use their skills with patients and customers.

Another part of Nutbeam’s critical health literacy component is a call to action in communities to improve health. Pharmacies could play a health advocacy role in their locality. Is there a need to promote breastfeeding-friendly places in the local community? Has a recent local DUMP campaign shown medicines wastage that needs to be brought to the attention of local prescribers, care home managers or, more widely, among local people? Does the trust miss opportunities to promote healthy lifestyles among inpatients? Issues such as these are valuable opportunities for promotion and taking co-ordinated action, and pharmacies are often central in communities, making pharamcists well placed to influence and inform.

Health competency

Later health literacy assessment tools are the Newest vital sign[5] and the eHealth literacy scale[6]. However, Swiss researchers are moving towards developing an instrument that specifically measures competencies for health literacy. The Swiss Health Literacy Survey identified 30 core competencies for health relevant to all citizens, which are measuable. This will now be applied and developed across other European countries through an EU-founded survey. The move towards the term “health competency” reflects the title of this article — that health literacy conjures up a narrow picture of health skills needed in our complicated system.

Although the concept of heath literacy will, no doubt, continue to evolve, its value is in sharing skills, not just information. Pharmacists and staff can be frontline health literacy activists, simply by being aware that the communication tools and information at their disposal can serve a dual purpose.

The value of a pharmacy health literacy intervention is to use opportunities in consultations to create and hone skills in patients and customers that can be used repeatedly in a variety of new health-related situations. Many of the developments in health literacy have been academic but it is now time to apply the concept to practice.

References

1. Nutbeam D. Health Literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International 2000;15:259-67.

2. Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant AF Greer DS. Advancing health literacy: a framework for understanding and action. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass/Wiley: 2006.

3. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW et al. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy: a shortened screening instrument. Family Medicine 1993;25:391-5.

4. Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a short test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Education and Counselling 1999;38:33—42.

5. Weiss B, Mays MZ, Martz W, Merriam Castro K, DeWalt DA, Pignone PA etal. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the Newest vital sign. Annals of Family Medicine 2005;3:514—22.

6. Norman CD, Skinner H. eHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2006; 14: 27.

7. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science and Medicine 2008; 67: 2072-8.

8. Miller MJ, Abrams M, McClintock B, Cantrell MA, Dossett CD, McCleeary EM etal. Promoting health communication between the community- dwelling well-elderly and pharmacists: the Ask Me 3 program. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2008; 48:784-92.

9. von Wagner C, Knight K, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Functional health literacy and health promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2007; 61:1086—90.