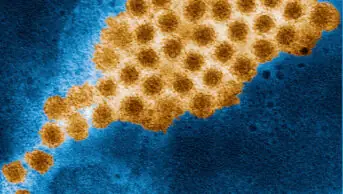

London School Hygiene & Tropical Medicines / SPL

This content was published in 2010. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Hepatitis, a general term meaning inflammation of the liver, can be caused by viral infection. The most serious viral cause is hepatitis B — a life-threatening liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). It can cause chronic liver disease, progressive hepatic fibrosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and end-stage liver disease.

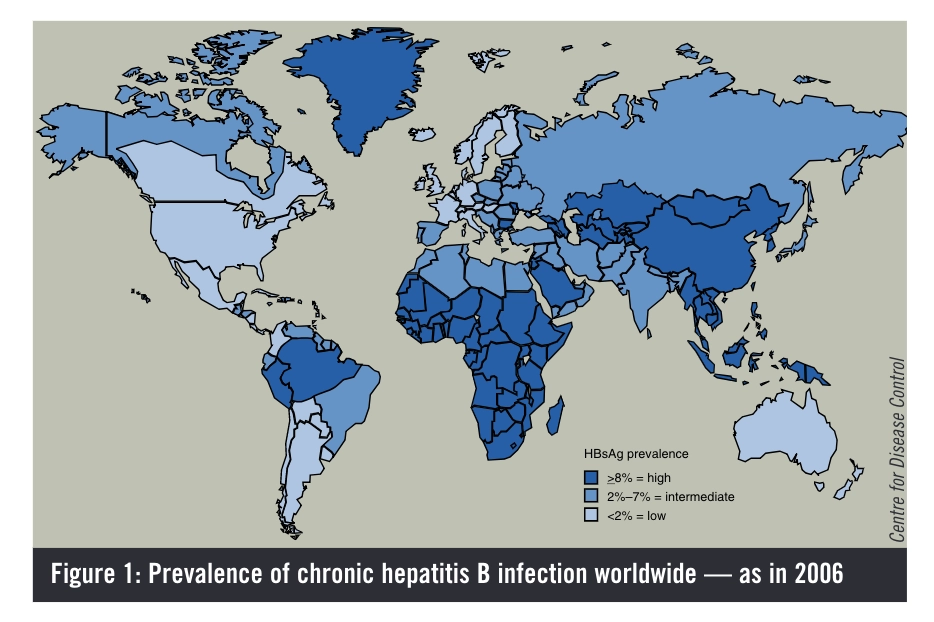

HBV can cause acute illness or chronic infection. Despite the availability of a highly effective vaccine and improvements in antiviral therapy, it remains a major public health problem globally. The prevalence of HBV infection varies in different parts of the world —from as low as 0.1% to as high as 20%.1 Figure 1 indicates how prevalence rates vary across the globe.

Population movements and migration are changing the prevalence and incidence of the disease. Immigration from high or medium prevalence areas is leading to increased incidence of disease in low prevalence areas. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated two billion people have been infected with HBV at some point in their lives. Approximately 350 million remain infected chronically and, of these, 25–40% will die of cirrhosis or liver cancer that is related directly to their infection.

The virus

HBV is an enveloped virus containing a partially double-stranded, circular DNA genome and is classified within the hepadnavirus family. It replicates within hepatocytes and, consequently, interferes with the function of the liver. The immune system tries to combat and eradicate the virus but this response, and the consequent release of inflammatory mediators, leads to liver inflammation and damage. Eight different genotypes of HBV have been identified(A–H), the prevalence of which vary within different countries. In Europe, genotypes A, D and G are most common. Data suggest that progression of the disease and responsiveness to treatment are related to the genotype identified (investigations to determine which genotypes are most difficult to treat are ongoing).2,3

Transmission

HBV transmission can occur in several ways, including:

- Through using contaminated injecting equipment, sustaining a needlestick injury or receiving a tattoo or body piercing (percutaneous or parenteral transmission)

- Through sexual intercourse with infected individuals

- Through contact with infected bodily secretions orblood

- From mother to child during childbirth

HBV is too large to cross the placenta so it cannot be transferred during gestation unless there is a break in the maternal-fetal barrier (eg, due to amniocentesis).1 However, the most common mode of transmission is perinatal transmission from mother to baby at birth.Around 90% of those infected at birth will go on to develop chronic HBV infection. Where infection occurs later in life, only 5–10% of patients develop chronic infection.

It is recommended that the offspring of infected women be treated with hepatitis B immunoglobulin at birth (to provide immediate protection). They should also be given the HBV vaccine as soon as possible after birth to improve long-term immunity.

Detection

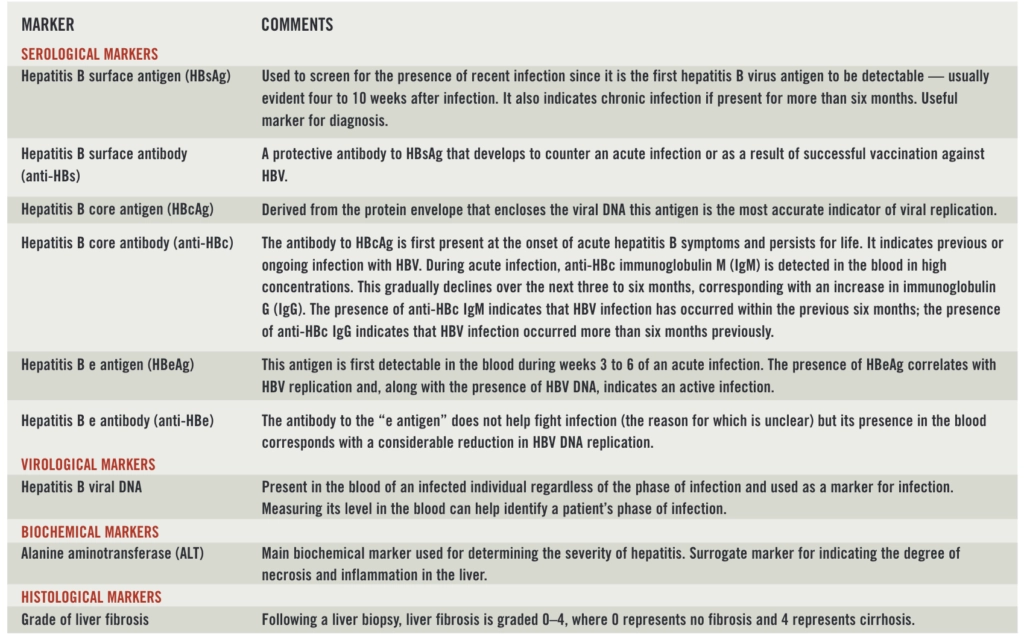

Hepatitis B is a complex disease and diagnosis is made by assessment of biochemical, serological, virological and histological parameters. The parameters used to define and characterise HBV infection are listed in Box 1.

Box 1: Markers of infection with hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is used to screen for the presence of infection.4 It is the first viral antigen to be detectable in the blood after infection — appearing during the virus’s incubation period. In 10% of patients, HBsAg is cleared early and may not be detectable when these patients are screened for HBV infection.

Shortly after HBsAg is detected, a second antigen(hepatitis B e antigen; HBeAg) becomes detectable. The presence of HBeAg signifies HBV replication and, along with the presence of HBV DNA (detected using polymerase chain reaction-based assays), indicates an active infection.

Antibodies to the hepatitis B core antigen are detectable in the blood after the onset of acute hepatitis B symptoms. These antibodies (anti-HBc) persist for life and their presence indicates previous or ongoing infection.The relative concentrations of anti-HBc immunoglobulinM and immunoglobulin G indicate the timeframe of infection (see comment on anti-HBc, Box 2).4

During the natural course of an infection, the HBeAg is sometimes cleared with a corresponding rise in its antibodies (anti-HBe). This is usually associated with a dramatic decline in viral replication and indicates resolution of acute hepatitis B infection. In patients who develop chronic hepatitis B, HBsAg and HBV DNA remain high for more than six months.5

Acute hepatitis B

The course of hepatitis B infection can be highly variable and different clinical manifestations present depending on the patient’s age (at the time of infection) and immune status and the extent to which the disease has progressed when it is identified.1

In adults, acute hepatitis B infection has an incubation period of 6–24 weeks. Following this period, acute hepatitis develops — patients will have elevated aminotransferase levels that can persist for four to 12weeks. Affected adults can develop symptoms of jaundice, anorexia, nausea, liver discomfort (usually originating in the right upper quadrant) and fatigue. This acute form of the disease often resolves spontaneously after four to eight weeks of illness. Most of those infected during adulthood clear the virus without significant consequences and without its recurrence. In about 1% of cases, fulminant hepatitis B develops causing extensive liver necrosis. This form of the disease is normally fatal.1,3

Chronic hepatitis B

Chronic HBV infection develops in 90% of those who are infected at birth. It also occurs in older patients whose immune systems fail to eradicate the virus completely after acute infection. It is diagnosed by the persistence ofHBsAg in a patient’s bloodstream for more than six months.

The clinical features of hepatitis B are a result of the interaction between HBV and the host’s immune system.The immune system attacks the hepatocytes that harbour the virus and thus causes liver injury. The WHO has reported that approximately one million deaths occur worldwide each year due to chronic forms of HBV infection — generally due to cirrhosis or cancer of the liver.

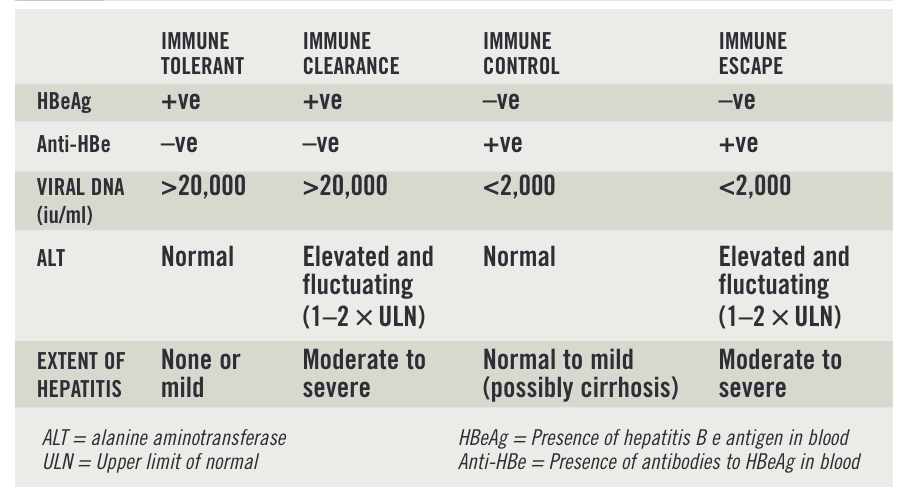

Patients with chronic HBV infection can progress through up to five phases of disease. Understanding these phases is critical to determining the risk of liver damage and the need to begin treatment (see Box 2). Patients can move from one phase to another at any time. In addition, they do not always move through the phases in sequence and can move from one phase to another and then go back again. Patients’ blood results should be monitored every three to six months to identify when their condition progresses.

Typically, chronic infection acquired perinatally or during infancy has all five phases — the first of which (the immune tolerant phase, see below) can last for decades. Adult-acquired chronic infection has a similar clinical course but there is often no obvious immune tolerant phase. The five phases are described hereafter.3,6,7,8

Box 2: Identifying the phase of infection

Immune tolerant phase

This is characterised by high levels of viral replication (patients’ blood tests are positive for HBeAg) and normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. As discussed, this phase usually only occurs in patients who acquire the infection at birth. During this phase, the virus is not recognised as a foreign body because the immune system has not matured fully. Consequently, the immune system does not attempt to remove it. Minimal damage occurs to the liver so treatment is not recommended. However, patients should have their liver function tested periodically so that any rise in ALT is detected early.

Immune clearance phase

The immune clearance phase signifies a vigorous immune response resulting in liver damage. It is characterised by the presence of HBeAgin the blood along with fluctuating and elevated levels ofALT, and high levels of viral DNA. Repeated episodes of inflammation lead to liver fibrosis and the duration and severity of this phase determine the degree of long-term liver damage. Treatment should be started as soon as possible to prevent progressive liver fibrosis. Left untreated, patients are more likely to develop cirrhosis, liver failure and cancer.

Immune control phase

During the immune control phase, the host’s immune response suppresses viral replication to low or undetectable levels. As a result, inflammation reduces and serum ALT normalises. The establishment of immune control is associated with HBeAg seroconversion — anti-HBe is present in the blood, corresponding with the removal of HBeAg.This phase does not require antiviral treatment; however, the infection can reactivate at any time and patients in this phase should still undergo regular monitoring. Prophylactic treatment is recommended if patients require immunosuppressive therapy, such as chemotherapy.

Occult HBV infection

Occult HBV infection refers to the presence of viral DNA in the blood or liver without levels of the HBsAg being detectable. The presence of theDNA may be related to the long-term persistence of aHBV DNA reservoir in hepatocytes. The reactivation of hepatitis B infection following immunosuppression has been described in patients with occult infection although the clinical relevance of this phase is unclear.9

Effects on health

As the clinical course of chronic HBV infection varies between patients, clinical outcome and prognosis also vary. The lifetime risk of death caused by a liver-related complication has been estimated to be 40–50% for men and around 15% for women.1

Morbidity and mortality are linked to the persistence of viral replication and the development of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Studies suggest that 15–20% of chronic hepatitis B patients develop cirrhosis within five years of their diagnosis. Whether cirrhosis is compensated or decompensated (see Box 3) has a significant impact on a patient’s chances of survival. Around 15% of patients with compensated cirrhosis will die within five years, compared with 60% of those with decompensated cirrhosis.

Box 3: Classifying liver damage

Vaccination

Understanding the routes and modes of transmission can prevent further transmission of the virus. An effectiveHBV vaccine has been available since the early 1980s. In the early 1990s, the WHO recommended the addition of the HBV vaccination to all national immunisation programmes. The WHO strategy aims to provide the first dose of the vaccine to infants at birth. Introducing this type of vaccination program in Taiwan, a country with a high prevalence of HBV infection, has reduced the proportion of children who are HBsAg-positive from 10%to 1%.10

In the UK, vaccination is only recommended for certain “at risk” individuals, such as:

- Intravenous drug misusers

- Partners and children of patients with chronic HBV infection

- Healthcare workers

- People with haemophilia

- Patients with chronic renal failure

References

1 World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. 2002. www.who.int/csr (accessed 15 December 2009).

2 Pan CQ, Zhang JX. Natural history and clinical consequences of hepatitisB virus infection. International Journal of Medical Sciences 2005;2:36–40.

3 Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. The Lancet 2009:373:582–92.

4 Locarnini S. Virology: viral replication and drug resistance. In: Matthews G, Robotin M, eds. B positive: all you wanted to know about hepatitis B.Sydney: Australasian Society for HIV Medicines Inc; 2008. pp24–30.

5 Danta M. Hepatitis B virus testing and interpreting test results. In: Matthews G, Robotin M, eds. B positive: all you wanted to know about hepatitis B. Sydney: Australasian Society for HIV Medicines Inc; 2008.pp31–39.

6 Bell SJ, Nguyen T. The management of hepatitis B. Australian Prescriber2009;32:99–104.

7 European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practiceguidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Hepatology 2009;50:227–42.

8 Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Dusheiko G, et al. Therapeuticstrategies in the management of patients with chronic hepatitis B virusinfection. Lancet infectious Diseases 2008;8:167–78.

9 Guirgis M, Zekry A. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection.In: Matthews G, Robotin M, eds. B positive: all you wanted to knowabout hepatitis B. Sydney: Australasian Society for HIV Medicines Inc;2008. pp40–5.

10 Ni YH, Huang LM, Chang MH, et al. Two decades of universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan: impact and implication for future strategies. Gastroenterology 2007;132:1287–93.

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control