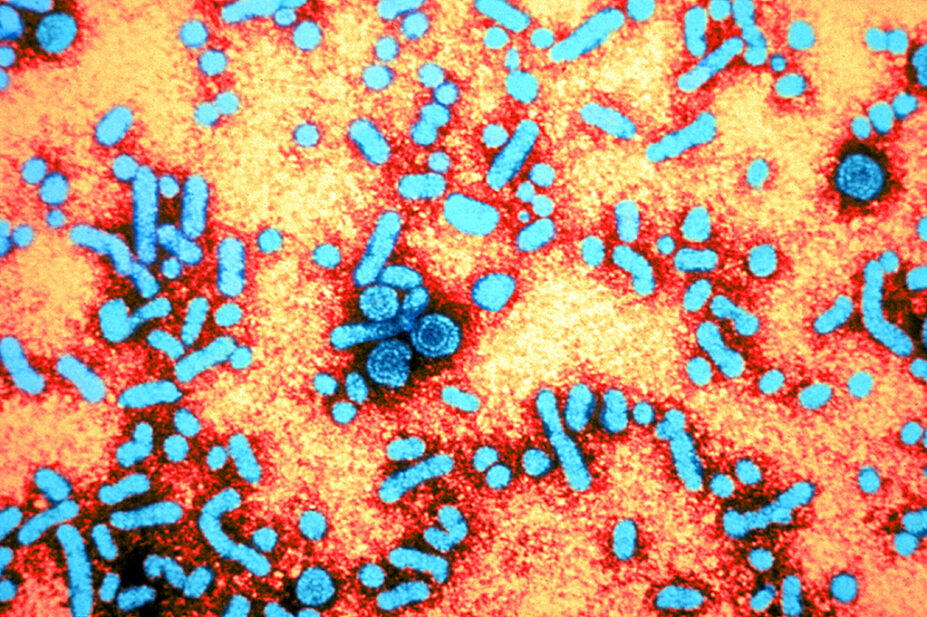

Science History Images / Alamy.com

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the aetiology and pathophysiology of hepatitis B;

- Understand the importance of hepatitis B prevention as part of the long-term elimination strategy;

- Know how hepatitis B is diagnosed and managed;

- Contribute towards ongoing monitoring of hepatitis B patients.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a significant global public health issue, and pharmacists have a vital role to play in reducing the negative effects of the disease1–3. While hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, hepatitis B is a liver infection caused by HBV.

Data reveal that, in 2022, an estimated 1.2 million new HBV infections occurred globally, while 254 million people were living with chronic HBV infection. In the same year, hepatitis B-related complications — including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) — contributed to 1.08 million deaths. Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific Islands have the highest prevalence of the disease4,5.

In Europe, the eastern and southeastern regions are most affected by HBV. Data show that HBV prevalence rates are as high as 6–8% of the population in some countries in those regions. While the UK has a relatively low number of cases, the UK Health Security Agency estimated that there were more than 268,000 cases of chronic HBV in England in 20224–8.

Geographical variation of prevalence continues to evolve, owing to migration, movement of refugees and long-term globalisation trends5. The UK is a signatory to the World Health Organization (WHO) global health strategy on viral hepatitis, which aims to achieve the following targets by 20304:

- 90% reduction in new chronic HBV infections;

- 65% reduction in HBV-related mortality;

- 90% of people living with HBV diagnosed;

- 80% of eligible individuals receiving treatment.

The UK has made progress towards these goals. For instance, hepatitis B antenatal screening rates remain high (e.g. 99.8% for England in 2024), and mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is close to elimination, with birth dose vaccine coverage for infants born to women with hepatitis B infection at 98.8%6. However, challenges still remain. The WHO metric of elimination of MTCT is 0.1%, while the most recent seroprevalence data from England taken in 2022 were geographically limited, making it challenging to ascertain the veracity of elimination claims6.

Many individuals are unaware of their infection and, among those eligible for treatment, a significant proportion of them are not receiving it. This was highlighted when 646 new hepatitis B patients were diagnosed between April 2022 and March 2023, under a three-year emergency department opt-out testing programme conducted in London, Brighton, Manchester and Blackpool6.

There is a need for a targeted approach to prevent HBV transmission through case finding, early diagnosis and vaccination, especially in migrant or vulnerable populations who are disproportionately affected6,8. There is also a gradual acceptance that HBV is a cancer-causing virus. As a result, hepatitis B prevention is being increasingly recognised as a component of cancer prevention strategy6.

Pharmacists play a vital role in the multidisciplinary management of HBV across clinical settings. Community pharmacy teams contribute to vaccination delivery to at-risk groups, health promotion and education, as well as signposting at-risk people to testing services and specialist care2. In primary care, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will support patients with medication reviews, including interaction checking and monitoring of liver function1,2.

Pharmacists are also at the forefront within specialist clinics and secondary care settings in the management of viral diseases, including hepatitis B. There are pharmacist-led clinics across the UK, offering ongoing monitoring and therapy adjustment1,3.

This article will provide an overview of hepatitis B, summarising how it is diagnosed and treated, as well as the ways in which pharmacists can contribute to prevention efforts and the ongoing monitoring of patients.

Pathophysiology

HBV is blood borne and is mainly transmitted by percutaneous or mucosal exposure to the infected blood or body fluids of a patient, which can include menstrual or vaginal fluids, semen or, rarely, saliva4,9. Transmission can occur if proper needle hygiene practices are not adhered to (e.g. when getting a tattoo or intravenous drug use) or if sexual behaviour considered a risk is engaged in3,4,10,11.

HBV is a small, enveloped DNA virus from the Hepadnaviridae family, primarily infecting hepatocytes. After entering the bloodstream, HBV targets the liver, where it replicates within hepatocytes using reverse transcription4,9. The incubation period is 40–160 days12.

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognise and destroy infected hepatocytes, causing liver injury (i.e. hepatitis) with the degree of liver damage influenced by the strength and nature of the immune response. The rise in liver alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in acute patients is a result of the immune response5,13,14.

The clinical course of HBV infection can be acute or chronic:

- Acute infection is often asymptomatic but may present with jaundice, fatigue and elevated liver enzymes. Rarely, it can lead to severe hepatitis. In some cases, fulminant hepatitis (i.e. rapid liver necrosis and hepatic encephalopathy) and liver failure. Data show that the fatality rate in acute infection is 0.5–1%5,11,13.

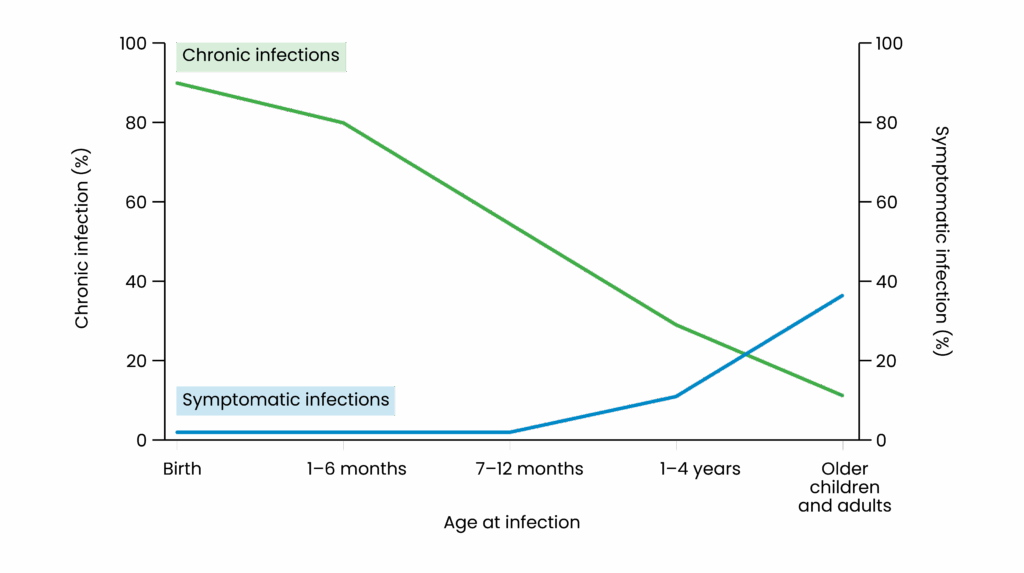

- Chronic infection is defined as persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for more than six months. Chronicity risk is inversely related to age at infection — infants are more likely to develop chronic infection (up to 90–95%), while <5% of adults do (see Figure 1)4,10.

Figure 1: Relationship between chronicity of hepatitis B and age of infection

Depending on several factors — including viral load, co-infection and age — there is an 8–20% risk of developing liver cirrhosis over five years in untreated chronic sufferers5. For those with liver cirrhosis, data show that the cumulative risk of having decompensated cirrhosis is 5–7% per year. This is important to prevent because when liver decompensation occurs, median survival drops from over 12% in compensated to approximately 2% in decompensation stage15. Hepatitis B sufferers can also develop extrahepatic manifestations, such as HBcAg-positive glomerulonephritis, dermatological, rheumatologic and vascular issues16. Both chronic and resolved HBV infections carry a risk of reactivation in individuals having immunosuppressant treatment, which can lead to severe and potentially fatal outcomes5.

Prevention

Vaccination is the cornerstone of HBV prevention. The UK introduced universal infant HBV vaccination in 2017. As of 2024, data show that 91.8% of infants receive all three doses by 12 months of age6. Pharmacists are well placed to refer at-risk patients to sexual health clinics and GPs for vaccination.

Other vaccination strategies include:

- Targeted vaccination for high-risk groups, such as people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), healthcare workers and individuals with chronic liver disease12;

- Antenatal screening and neonatal immunoprophylaxis6 to prevent MTCT.

Vaccines used in the UK include Engerix-B, HBvaxPRO and Fendrix. Fendrix is recommended for patients with renal insufficiency, as it contains an adjuvant that enhances the immune response17. A full course of Fendrix involves three doses over six months, with an accelerated schedule reserved for special circumstances (e.g. post-exposure prophylaxis). The Green Book should be consulted for the most up-to-date vaccine schedule18. It should also be noted that the routine childhood vaccination schedule for Wales changed in July 2025. The main changes were around the timing of some vaccines to provide earlier protection to children and reduce duplication of unnecessary vaccines19.

Public health campaigns focusing on modes of transmission, testing, vaccination and access to treatment are essential in reducing transmission risk, especially among people who inject drugs and migrant populations6,18.

Proactive testing has proven to be an effective method of case finding. Some UK hospitals with high prevalence rates or at-risk populations have implemented opt-out bloodborne virus (BBV) testing in emergency departments and were able to identify hundreds of new HBV cases6.

HMP Berwyn in Wrexham, which is the largest prison in Europe, implemented opt-out testing, invested in the provision of specialist pharmacists and BBV nurses and was able to achieve a micro elimination of hepatitis C in 2024. The same principles could be used to reduce transmission and achieve elimination of hepatitis B in other prison populations or hotspots20.

Routine screening is recommended for pregnant women, blood and organ donors, individuals from high-prevalence countries, people with HIV or hepatitis C, individuals with abnormal liver function and household and sexual contacts of HBV-positive individuals11. While this list is not exhaustive, patients outside of this list may also be screened if clinically appropriate.

Diagnosis

A full serological panel is essential to determine infection status, immunity and need for vaccination or treatment11,12. Table 1 provides a summary of how serology tests for hepatitis B can be interpreted11.

If a person is HBsAg positive, they are hepatitis B positive. IgM anti-HBc denotes that it is acute, and HBsAg will need repeat testing in six months to determine if chronic disease has been developed. Developing antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) denotes a past infection or immunity owing to vaccination. Antibodies to HBcAb (anti-HBc) can be acute, chronic or occult infection but not owing to vaccination, while HBeAg shows the degree of infectivity of the disease. Hepatitis DNA is the genetic material of the hepatitis virus and quantifies viral load and response to treatment. Hepatitis e antigen (HBeAg) is a viral protein produced by the hepatitis B virus and is a marker of high infectivity and active replication of wild type virus. Anti-hepatitis B e-antigen/hepatitis B e-antibodies (anti-HBeAg) denote improved prognosis by the body producing antibodies to HBeAg (i.e. seroconversion or disappearance of HBeAg)5.

A baseline liver disease assessment should be done for all patients diagnosed with hepatitis B, including an abdomen ultrasound. If appropriate, a full liver aetiology screen, which includes screening for Hepatitis A, C, D, E, HIV, liver auto antibodies, serum ferritin and transferrin saturation and serum immunoglobulins, and vaccinations should be offered.

Treatment

Acute and chronic hepatitis B infection require different treatment strategies.

Acute hepatitis B

The treatment goal for patients with acute hepatitis B infection is to prevent the risk of acute or subacute liver failure and monitor for further review if chronicity develops. Acute hepatitis B infection is not routinely treated with antivirals unless there is severe or fulminant hepatitis, in which case a hepatologist specialist referral is required at that point. Starting an acute infected patient on antivirals will not increase their risk of developing chronicity5.

Chronic hepatitis B infection

The main treatment goal for patients with chronic hepatitis B infection is to improve survival and quality of life by preventing disease progression and reducing the risk of HCC development by suppressing HBV DNA. Treatment also prevents MTCT, reactivation in immunosuppressed patients and prevents HBV-associated extrahepatic manifestations, such as non-rheumatoid arthritis and glomerulopathies, which are normally immune mediated5,7,11,16.

Although all patients with detectable HBV DNA are candidates for antiviral therapy, indication for treatment in chronic diseases depends on HBV viral load, liver status, risk of HCC/liver disease progression and comorbidities. There are different treatment criteria depending on your reference and the patient’s status. However, according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)5, most agree that the following criteria indicates a need for pharmaceutical intervention:

- Patients with HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, HBV DNA level >2,000 IU/ml and elevated ALT (>ULN) and/or significant fibrosis;

- Patients with cirrhosis should be treated if HBV DNA is detectable, regardless of the level of viraemia and serum ALT;

- Patients with advanced liver disease — corresponding to Metavir fibrosis score ≥F3 on liver histology or defined by a LSM >8 kPa — can be treated if HBV DNA is detectable, regardless of the level of viraemia and serum ALT.

Other criteria to be considered for antiviral therapy treatment include:

- Family history of HCC or HCC patients, co-infection with HIV, HCV or hepatitis D and pregnant women in the third trimester with viral load >200,000;

- Immunosuppressed individuals (e.g. undergoing chemotherapy or biologic therapy) to prevent HBV reactivation, depending on the risk factor of the medication — refer to the hepatitis B reactivation policy of your board/hospital;

- Pregnant women with HBV DNA >200,000 international units/mL, to prevent vertical transmission;

- Children and adolescents — treatment decisions are based on age, viral load, ALT and liver histology, while managed by the paediatric hepatology team.

This list is not exhaustive, and individual patients may need assessment to determine their eligibility5,7,11.

Therapeutic options

First-line antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis B are tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and entecavir (ETV)5,7,8. Tenofovir-based antivirals and entecavir are recommended over other antivirals such as lamivudine, owing to their high barrier for development of viral resistance since multiple mutations of the HBV virus is needed to confer resistance. These therapeutic options have potent antiviral activity and are supported by long-term clinical data5. Please refer to the summary of product characteristics (SPC) for further information.

Interferon-based therapy is less commonly used, owing to the risk of side effects, but may be considered in select patients aiming for functional cure (i.e. HBsAg loss). These therapies have the potential advantage of being a treatment with a finite duration if the patient responds well. However, unfortunately, interferon-based therapies carry a low percentage of success5,7.

Treatment duration with antivirals is normally lifelong, owing to the low percentage of seroconversion (i.e. the loss of HBsAg in positive patients and the production of antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBsAg))5. If seroconversion (i.e. the loss of HBsAg and the production of anti HBsAg) is confirmed in two separate tests, six months apart, treatment may be stopped. However, there should be an increased frequency of monitoring for hepatic flare up, and testing for acute liver failure will be required. The decision to stop treatment needs to be taken collaboratively between the medical team and the patient5. One study in Asia of over 4,000 patients who achieved HBsAg seroconversion, published in 2022, showed that after stopping their medications, 95% of patients maintained their seroconversion, although further studies are required to help stratify patients that will benefit from stopping antivirals5. There are also ongoing trials and studies looking at possible benefits of stopping treatment, theorising that this will prompt the immune system to regenerate and subsequently clear the disease (i.e. the seroconversion of HBsAg positive to anti-HBsAg)21.

All patients should be advised on the benefits of positive lifestyle changes (e.g. abstaining from alcohol, not smoking and healthy eating)11.

Special populations

Tenofovir disoproxil is the recommended antiviral in pregnant patients and normally prescribed during the third trimester to reduce vertical transmission5,11,22.

Chronic hepatitis does not preclude someone from practising as a health worker; however, health workers performing exposure prone procedures should be treated with antiviral therapy if their HBV DNA >200iu/ml5.

Monitoring

Monitoring depends on the disease status. In acute hepatitis B infection, liver function status should be monitored every two to four weeks, while HBV surface antigen should be monitored after six months to assess for seroconversion. If deranged liver function test is present, it should be treated as per local protocol for liver impairment5.

If there is no seroconversion to hepatitis B surface antibodies and the patient is still positive for HBsAg after six months, then they will need to be managed as a chronic patient. For chronic patients, monitoring depends on whether they are on medication or active monitoring without medications.

Active monitoring without medications

Depending on the patient’s HBeAg status and HBV DNA level, the following monitoring should be provided:

- ALT, HBV DNA should be tested every 6–12 months;

- If HBeAg positive HBeAg/HBeAb, seroconversion should be measured yearly;

- HBsAg quantitative every 12 months;

- A fibrosis assessment with fibroscan should be made every 12–24 months based on clinical assessment.

Active monitoring of patients on medications

Monitoring is done every 3–6 months for the first year, then every 6–12 months when virological response is achieved (i.e. HBV viral load is undetectable). Assessment parameters are HBV DNA, ALT (LFT), HBsAg and HBeAg (to assess seroconversion) and renal function. A non-invasive liver assessment (e.g. fibroscan) is completed every two to three years. Monitoring will also include pharmaceutical review of polypharmacy, interactions, compliance and deprescribing as appropriate23.

HCC monitoring

Active treatment does not reduce HCC risk in some patients. There are numerous risk scores used for HCC monitoring. EASL recommends the PAGE-B score, which uses a patient’s age, platelets and sex and classifies results as low risk (<0-9), intermediate (10-17) and high (>18) to developing HCC. Surveillance is recommended in intermediate and high-risk groups; however, low-risk individuals should be evaluated at every clinic attendance to review if there are any changes to their risk status5.

The PAGE-B risk score is validated mainly among patients of white ethnicity and may perform differently in other racial groups. Individual assessment for patients not of white ethnicity may be included when determining their HCC risk (e.g. age of transmission, family risk, etc.)5.

All liver cirrhosis patients who are candidates for liver transplantation should be monitored for HCC5.

Standard HCC surveillance is conducted every six months and involves abdomen ultrasound with alpha- fetoprotein testing. A contrast-enhanced CT scan or MRI may be used if ultrasound is difficult to perform or provides inadequate results5,7,11.

Reactivation

Reactivation refers to the risk of an occult HBV infection seroconverting to HBsAg positive or chronic HBV infection, causing hepatitis flare up/reactivating owing to immunosuppressive therapy. Prophylactic antiviral therapy is recommended for at-risk individuals before starting immunosuppression5,11,24. Risk assessment depends on the immunosuppressive remedy and the patient’s HBV infection status. Refer to local reactivation guidelines or contact local hepatology pharmacists or teams for recommendations.

- 1.Pharmacists Can Identify, Prevent, and Treat Viral Hepatitis. Pharmacy Times. 2022. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacists-can-identify-prevent-and-treat-viral-hepatitis

- 2.Pharmacists play bigger role in helping manage liver patients. London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust. 2024. https://www.lnwh.nhs.uk/news/pharmacists-play-bigger-role-in-helping-manage-liver-patients-9977

- 3.Sharma S, Carballo M, Feld JJ, Janssen HLA. Immigration and viral hepatitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;63(2):515-522. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.026

- 4.Elimination of hepatitis by 2030. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hepatitis/elimination-of-hepatitis-by-2030

- 5.Cornberg M, Sandmann L, Jaroszewicz J, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2025;83(2):502-583. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2025.03.018

- 6.Hepatitis B in England. UK Health Security Agency. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-b-in-england/hepatitis-b-in-england-2024

- 7.Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. World Health Organization . 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090903

- 8.WHO Factsheet. World Health Organization. July 2022. https://www.who.int/docs/librariesprovider2/default-document-library/hepatitis-b-in-the-who-european-region-factsheet-july-2022.pdf

- 9.Pyrsopoulos N. Hepatitis B: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Medscape. February 2025. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/177632-overview

- 10.Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B Virus Infection — Natural History and Clinical Consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1118-1129. doi:10.1056/nejmra031087

- 11.Hepatitis B (chronic): diagnosis and management – Clinical guideline CG165. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . October 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG165

- 12.Hepatitis B: clinical and public health management. Gov.uk. July 2025. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/hepatitis-b-clinical-and-public-health-management

- 13.Seto WK, Lo YR, Pawlotsky JM, Yuen MF. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. The Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2313-2324. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31865-8

- 14.Clinical Overview of Hepatitis B. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . August 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- 15.Mansour D, Masson S, Corless L, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology Best Practice Guidance: outpatient management of cirrhosis – part 2: decompensated cirrhosis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023;14(6):462-473. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2023-102431

- 16.Najafian N, Han SH. Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis B. Curr Hepatology Rep. 2023;22(3):147-157. doi:10.1007/s11901-023-00603-w

- 17.Fendrix overview. European Medicines Agency. 2008. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/fendrix

- 18.Green Book. UK Health Security Agency. March 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-b-the-green-book-chapter-18

- 19.Changes to the childhood immunization schedule. Public Health Wales. https://phw.nhs.wales/topics/immunisation-and-vaccines/changes-to-the-childhood-immunisation-schedule/

- 20.Hepatitis C micro-elimination in HMP Berwyn, the UK’s largest prison. NHS Wales. 2024. https://performanceandimprovement.nhs.wales/functions/quality-safety-and-improvement/improvement/nhs-wales-awards/2024/team-culture/bcuhb-hepatitis-c-hmp-berwyn/

- 21.van Bömmel F, Stein K, Heyne R, et al. A multicenter randomized-controlled trial of nucleos(t)ide analogue cessation in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Hepatology. 2023;78(5):926-936. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.12.018

- 22.Guide to Management of Hepatitis B infection. NHS Tayside. March 2019. https://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/approved/guidance/Management%20of%20Hepatitis%20B%20Infection.pdf

- 23.Razavi-Shearer D, Gamkrelidze I, Pan C, et al. Global prevalence, cascade of care, and prophylaxis coverage of hepatitis B in 2022: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2023;8(10):879-907. doi:10.1016/s2468-1253(23)00197-8

- 24.NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Hepatitis B Reactivation Guideline. 2020. https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/media/1857/hepatitis-b-reactivation.pdf

You might also be interested in…

Case-based learning: insect bites and stings

Management of cold and flu symptoms