ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Summary

Most modern methods of contraception are safe to use for the majority of women. However, there are a few absolute contraindications. The World Health Organization has published Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for contraception use, which give evidence based, concise summaries of contraindications to use of contraceptives, where category 1 has no restriction to use, and category 4 indicates that the condition has unacceptable risk if that method were used.

All hormonal contraceptives can be started on up to day five of a normal menstrual cycle without the need for additional contraception. At any other time, a woman may start hormonal contraceptive if it is reasonably certain that she is not pregnant.

There are currently three methods available for emergency hormonal contraception: copper intrauterine device (used within five days of unprotected sexual intercourse or within five days from the earliest estimated date of ovulation); levonorgestrel (taken as a 1.5mg single oral dose up to 72 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse); and ulipristal acetate (taken as a 30mg single oral dose up to 120 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse).

In 2012, there were an estimated 884,748 conceptions in England and Wales. This included a greater number of women than ever before conceiving after the age of 35 years. At the same time, conception in women aged under 18 years was the lowest since 1969, at 27.9 conceptions per 1,000 women aged 15–17 years. However, despite rapid improvements in choice, efficacy and side effect profiles of birth control, many of these pregnancies are unplanned, and 20.8% of pregnancies in England and Wales end in abortion[1]

. Many of these could have been prevented by a method of contraception.

Not all women want to use regular methods of contraception all the time, so it is important to ensure that women have access to the right contraception that is most appropriate for their needs. There are various methods available ranging from pills, injections, devices that are inserted into the uterus/vagina (sub-dermally or placed transdermally) as well as barrier methods used at the time of sex. This article focuses on hormonal contraception.

In essence, hormonal methods of contraception work in one of three ways: inhibition of ovulation, thickening of cervical mucus (which prevents sperm entry) and endometrial effects that prevent implantation.

Most modern methods of contraception are safe to use for the majority of women. However, there are a few absolute contraindications, as well as some relative contraindications that require careful discussion about the risks and benefits. The World Health Organization (WHO) has published Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for contraception use, which give evidence based, concise summaries of contraindications to use of contraceptives[2]

. The UK has its own version (UK MEC), which is also evidence-based[3]

. Both MECs have four categories that indicate the risks associated with a particular condition ordered from 1 to 4: category 1 has no restriction to use and category 4 indicates that the condition has unacceptable risk if that method were used.

All hormonal contraceptives can be started on up to day five of a normal menstrual cycle without the need for additional contraception. At any other time, a woman may start hormonal contraceptive if it is reasonably certain that she is not pregnant (See ‘Criteria for excluding pregnancy’), but she must be advised to use additional precautions, such as condoms, for the following seven days[4]

.

A judicial review in the UK in 2002 ruled that pregnancy begins at implantation and not fertilisation. This is an important consideration when discussing modes of action, particularly with emergency hormonal contraception (EHC), as some people may have their own beliefs about the onset of pregnancy and abortion[5]

.

| Criteria for excluding pregnancy |

|---|

| A pregnancy test can be done but only if more than three weeks since the last time she had unprotected sex |

Health professionals can be “reasonably certain” that a women is not currently pregnant if any one or more of the following criteria are met and there are no signs or symptoms of pregnancy:

|

Combined hormonal contraception

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC) works by inhibiting ovulation on the hypothalamo-pituitary-ovarian axis. There are currently three methods available: the combined oral contraceptive pill (COC), combined transdermal patch (CTP) and combined vaginal ring (CVR)[5]

. A Cochrane review comparing the patch, ring and pill found that they all have similar efficacies; the failure rate is 0.3% with perfect use, and 9% with typical use (which includes inconsistent or incorrect use)[6]

.

According to UK MEC, CHC is suitable for most women except for when there are unacceptable health risks (UK MEC category 4):

- Breastfeeding and less than six weeks postpartum;

- Women aged over 35 years who smoke >15 cigarettes a day;

- Multiple cardiovascular risks (e.g. older age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and obesity);

- Consistently raised blood pressure >160/95mmHg;

- Vascular disease;

- History of or current venous thromboembolism (VTE), ischaemic heart disease or stroke;

- Major surgery with prolonged immobilisation (because of VTE risk);

- Known thrombogenic mutation (e.g. Factor V Leiden, Protein S, Protein C deficiency);

- Complicated valvular and congenital heart disease;

- Migraine with aura (migraine without aura is UK MEC 2);

- Current history of breast cancer (past history and no evidence of disease >five years is UK MEC 3);

- Diabetes with nephropathy, retinopathy, or neuropathy (UK MEC 3 or 4);

- Benign hepatocellular adenoma and malignant hepatoma;

- Raynaud’s disease with lupus anticoagulant;

- Systemic lupus erythamatosus with positive or unknown anti-phospholipid antibodies.

The COC pill, combining both oestrogen and progestogen, is the most commonly used contraceptive method in the UK and many other countries. The oestrogen in COCs is usually synthetic (e.g. ethinylestradiol), except for Qlaira (Bayer), which contains natural oestrogen, estradiol valerate. The progestogens are the same as in progestogen-only contraceptives (see below).

Most COCs marketed in the UK are monophasic (i.e. fixed dose) pills with between 20µg to 35µg ethinylestradiol. Most are packaged in strips of 21 pills; the first seven days of treatment act to inhibit ovulation, and the latter 14 maintain anovulation. The monophasic pill does not need to be synced with the woman’s natural cycle. A week’s break is usually taken before starting the next strip of 21 pills, during which a withdrawal bleed occurs because of endometrial shedding from withdrawal of hormones. Some COCs have seven placebo pills in the pack to take during this period. There are also biphasic and triphasic pills available, where there are two or three different doses of ethinylestradiol and progestogens respectively depending on the week.

The CTP delivers 34µg of ethinylestradiol and 203µg of norelgestromin over 24 hours. One patch is applied every week for three weeks; patches are then omitted for one week to induce a withdrawal bleed, after which a new patch is applied.

The next cycle of patches or pills should be started after a week, regardless of whether the woman has had a withdrawal bleed. However, if a bleed has not occured a pregnancy test should be performed before restarting treatment.

The CVR is inserted into the vagina, and delivers 15µg of ethinylestradiol and 120µg etonogestrel over 24 hours. Each CVR is used for 21 days, followed by a seven-day break from the CVR which induces a withdrawal bleed. A new CVR is then inserted.

CTP users have more breast discomfort, dysmenorrhoea, nausea and vomiting compared with COC users[6]

. CVR users report less nausea, acne, irritability and depression compared with COC users, but can experience more vaginal irritation and discharge.

Progestogen-only pills

Progestogen-only pills (POPs), unlike COCs, are taken with no pill-free interval. They need to be taken daily at or around the same time each day. POPs available in the UK include those that contain levonorgestrel, norethisterone and desogestrel, while products containing lynestrenol and norgestrel are also available in other countries. Ethynodiol diacetate (Femulen; Pfizer) has been discontinued in the UK. POPs are very safe and unlike CHCs there are very few absolute contraindications (i.e. UK MEC 4), apart from current history of breast cancer[7]

.

POPs thicken cervical mucus, thereby preventing sperm penetration into the uterus. It usually takes two days for this effect to occur, but the effect is short-lived and therefore POPs need to be taken continuously.

POPs can suppress ovulation but this can be variable: up to 60% of cycles in women using levonorgestrel and up to 97% in those using desogestrel[8],[9]

. Other effects include endometrial changes that render it hostile for implantation of a fertilised egg, and a reduction in cilia in fallopian tubes which slows down the passage of an ovum.

Altered bleeding patterns are common with POPs, with prolonged bleeding reported in 50% of users and spotting reported in 70% of users. Depression and mood changes are common with hormonal contraception but there is no evidence for direct causation. There is no good evidence to establish an association between POPs and headaches, a delay in return to fertility, weight changes or reduced libido. There is currently no adequate evidence to suggest POPs are less effective in women with a body mass index (BMI) >30.

A trial that compared desogestrel with levonorgestrel reported a Pearl index (pregnancy rate in the population divided by 100 years of user exposure) of 1.41 for levonorgestrel and 0.17 for desogestrel[10]

. Desogestrel may be more effective than other progestogens, theoretically because it is more likely to suppress ovulation.

Progestogen-only injectable contraception

Progestogen-only injectable contraception refers to depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone enanthate; both are examples of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), defined as reversible contraception administered less than once a month. Progestogen-only injectable contraception works by inhibiting ovulation. Similar to other progestogen-based contraception, it can also thicken cervical mucus to limit sperm penetration and change endometrial lining, making it hostile for implantation[11]

.

Two formulations of medroxyprogesterone acetate are available in the UK: 150mg in 1ml for deep intramuscular injection (Depo-Provera; Pfizer), usually injected by a health professional into the gluteus maximus (upper outer quadrant to avoid sciatic nerve injury) or deltoid in the upper arm; and 104mg in 0.65ml for subcutaneous injection (Sayana Press; Pfizer), usually self-administered by the woman into the anterior thigh or abdomen.

Norethisterone enanthate 200mg in 1ml (Noristerat; Bayer) is administered by deep intramuscular injection. It is a thick, oily fluid, and the manufacturer advises warming the ampoule in warm water to reduce viscosity and to always administer the injection into the gluteal muscle.

As with POPs, there are few absolute contraindications to the use of injectable progestogens apart from current history of breast cancer. Unexplained vaginal bleeding and high cardiovascular risks are UK MEC category 3.

The most commonly reported side effect of progestogen-only injectable contraception is altered bleeding patterns that include: amenorrhoea, infrequent bleeding, spotting and prolonged bleeding; however, there is a trend towards less bleeding and amenorrhoea with increased duration of use, and counselling patients at initiation can improve continuation rates[12],[13]

.

The failure rate of progestogen-only injectable contraception is around 0.2% in the first year of use; with “typical use” the failure rate increases to 6%[14]

.

Progestogen-only implants

The progestogen-only implant contains a single non-biodegradable rod that is inserted sub-dermally into the skin. It is licensed to be used for up to three years. It contains 68mg of etonogestrel, which releases at a rate of around 60–70µg per day in the first few weeks, to 25–30µg at the end of the third year; the efficacy of the implant is not reduced[15]

.

The implant works primarily to prevent ovulation but, in common with other progestogen-only contraception, also thickens cervical mucus and thins the endometrial lining. A review from the United States estimates the risk of unintended pregnancy in the first year of use is 0.05%[14]

.

With the exception of current breast cancer, there are very few absolute contraindications to using the progestogen-only implant.

Changes to menstrual bleeding patterns may be an undesirable effect for many women. The bleeding pattern in the first three months is broadly predictive of future bleeding patterns for many women[16]

. One third of women may have infrequent bleeding; one fifth may have amenorrhoea and approximately one quarter may have prolonged or frequent bleeding.

Some women report changes in weight, mood and libido but there is little evidence of association with the implant.

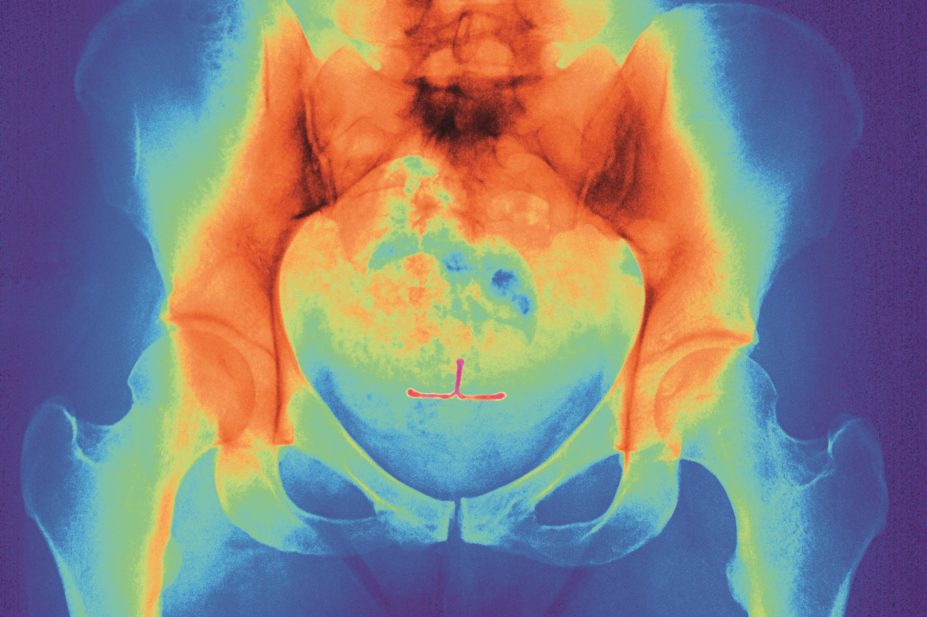

Since 2010, the etonogestrel 68mg implant (Nexplanon; MSD) has been used in the UK, replacing Implanon. Nexplanon contains barium sulphate, which helps detection of the implant on X-rays, and a redesigned applicator reduces the risk of deep insertion.

Emergency hormonal contraception

There are currently three methods available for EHC: copper intrauterine device (see ‘Intrauterine devices’); levonorgestrel (taken as a 1.5mg single oral dose up to 72 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse); and ulipristal acetate (taken as a 30mg single oral dose up to 120 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse)[17]

. Since June 2015, ulipristal acetate is licensed for any woman of reproductive age in Europe.

Levonorgestrel prevents ovulation for up to seven days (by which time any sperm would have become non-viable), but its precise mode of action as EHC is still unknown[18]

,[19]

. It appears to have no effect on the endometrial lining or implantation.

Ulipristal acetate is thought to inhibit or delay ovulation, and can also prevent ovulation after a surge of luteinising hormone[20]

. The effect on the endometrium and subsequent effects on implantation caused by ulipristal acetate are still unknown.

Headaches, nausea and an altered bleeding pattern are the most commonly reported side effects of both levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate. Current UK guidance recommends women should take a further dose if she vomits within two hours of taking levonorgestrel, or three hours after taking ulipristal acetate[4]

,

[21]

.

A meta-analysis has shown a pregnancy rate of 2.2–2.5% for levonorgestrel and 0.9–1.4% for ulipristal acetate taken between 0–120 hours[22]

.

There are no contraindications for using levonorgestrel as EHC. Breastfeeding is not recommended for up to 36 hours after taking ulipristal acetate[20]

.

Intrauterine devices

There are two types of intrauterine contraception: the copper intrauterine device and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. They are both LARCs and the length of use can vary from three to ten years.

Copper is toxic to sperm and ovum, so copper intrauterine devices primarily work in the pre-fertilisation stage; the endometrial inflammatory reaction has an anti-implantation effect but does not cause abortion.

There are many different types of copper intrauterine device available, with different copper content, sizes, and framed and non-framed versions. Devices with 380mm2 of copper and banded sleeves on horizontal arms appear to be the most effective (e.g. TT380 Slimline, TCu380A QuickLoad)[23]

. Spotting, light bleeding, heavier or longer periods are common in the first three to six months of use[4]

.

Because of the effect on gametes and implantation, copper intrauterine devices can also be used as an emergency contraception within the first five days of unprotected sexual intercourse, or within five days from the earliest estimated date of ovulation, although it is difficult to predict if a woman’s current menstrual cycle will be similar to her previous ones. The copper intrauterine device is more effective as emergency contraception than both EHC pills, with a failure rate of less than 1%[24]

.

There are two types of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system available in the UK – Mirena (Bayer, which is effective for five years) and Jaydess (Bayer, which is effective for three years). Jaydess has a smaller frame and narrower inserter tube.

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system mainly works by the progestogenic effect on the endometrium and prevents implantation. It also thickens cervical mucus to prevent sperm penetration. As the progestogen has a localised effect, the majority (>75%) of women continue to ovulate.

Amenorrhoea or light bleeding is common with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the first year of use; amenorrhea is more common than with the copper intrauterine device.

Menstrual pain and bleeding are the most common reasons for discontinuation of intrauterine contraception and are similar between both types of device[25]

. Systemic absorption of progestogen occurs with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, but women are no more likely to have hormonal side effects, such as acne, headaches, breast tenderness, nausea, mood, libido problems and weight gain, than those using copper devices.

Endometrial infection associated with puerperal sepsis and post-septic abortion are contraindications to intrauterine contraception (UK MEC 4). Intrauterine contraception should not be started in women with cervical and endometrial cancer, but if cancer develops after insertion, treatment can continue.

Richard Ma is a GP principal in London, and NIHR In-Practice Fellow at Imperial College London.

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] Office for National Statistics. Conception in England and Wales 2012. London: Stationary Office 2014.

[2] Department of Reproductive, Health World Health Organisation. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Geneva: World Health Organization 2009.

[3] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2009.

[4] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. UK Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2002.

[5] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance — Combined Hormonal Contraception. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2011.

[6] Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Gallo MF et al. Skin patch and vaginal ring versus combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010(3):Cd003552.

[7] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance — Progestogen-only Pills. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2015.

[8] Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 micrograms and levonorgestrel 30 micrograms daily. Hum Reprod 1999;14:982–985.

[9] Rice CF, Killick SR, Hickling D et al. Ovarian activity and vaginal bleeding patterns with a desogestrel only preparation at three different doses. Hum Reprod 1996;11:737–740.

[10] Collaborative Study Group on the Desogestrel-containing Progestogen-only Pill. A double-blind study comparing the contraceptive efficacy, acceptability and safety of two progestogen-only pills containing desogestrel 75 micrograms/day or levonorgestrel 30 micrograms/day. Eur J Contraception Reproductive Health Care 1998;3(4):169–178.

[11] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance — Progestogen-only Injectable Contraception. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2015.

[12] Canto De Cetina TE, Canto P & Ordonez Luna M. Effect of counseling to improve compliance in Mexican women receiving depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception 2001;63(3):143–146.

[13] Said S, Omar K, Koetsawang S et al. A multicentered phase III comparative clinical trial of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate given three-monthly at doses of 100 mg or 150 mg: II. The comparison of bleeding patterns. World Health Organization. Task Force on Long-Acting Systemic Agents for Fertility Regulation Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction. Contraception 1987;35(6):591–610.

[14] Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83(5):397–404.

[15] Faculty of Sexual and Re productive Healthcare. Progestogen-only Implants. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2009.

[16] Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M et al. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13:13–28.

[17] Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance — Emergency Contraception. London: Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2012.

[18] Marions L, Hultenby K, Lindell I et al. Emergency contraception with mifepristone and levonorgestrel: mechanism of action. Obstet & Gynecol 2002;100(1):65–71.

[19] Croxatto HB, Brache V, Pavez M et al. Pituitary-ovarian function following the standard levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive dose or a single 0.75-mg dose given on the days preceding ovulation. Contraception 2004;70(6):442–450.

[20] HRA Pharma UK Ltd. Summary of Product Characteristics. 2010.

[21] Bayer PLC. Summary of Product Characteristics. 2008.

[22] Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375(9714):555–562.

[23] Kulier R, Helmerhorst FM, O’Brien P et al. Copper containing, framed intra-uterine devices for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006(3):Cd005347.

[24] Cheng L, Gulmezoglu AM, Piaggio G et al. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2):Cd001324.

[25] French R, Van Vliet H, Cowan F et al. Hormonally impregnated intrauterine systems (IUSs) versus other forms of reversible contraceptives as effective methods of preventing pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3):Cd001776.