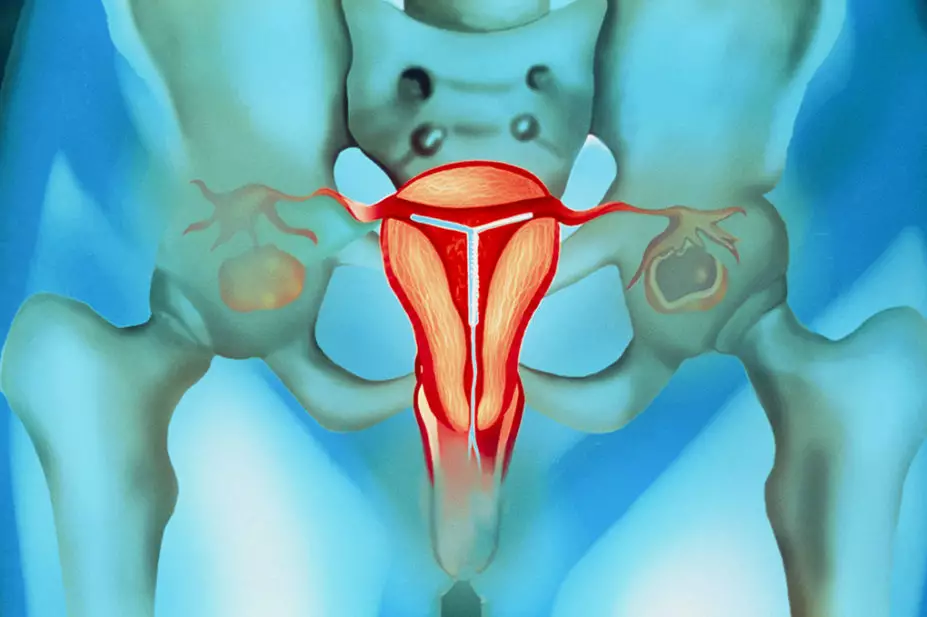

Science Photo Library

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Give advice on the use of different types of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including their mechanism of action, licensed duration and side effects;

- Understand the importance of aiding patients in making person-centred decisions regarding their contraception;

- Educate patients who may have misconceptions around the use of LARC;

- Recognise key interactions where promotion of LARC is appropriate.

Effective contraception is vital in the prevention of unplanned pregnancy, reducing abortion rates and avoiding short interpregnancy intervals that are associated with poor pregnancy outcomes[1]. Short-acting contraception, including the combined pill, transdermal patch, vaginal ring and progestogen-only pill, provides contraception that is more than 99% effective if used perfectly; however, with typical use, their contraceptive failure rate in the first year of use is around 9%[2]. For condoms, typical use failure rate is estimated at around 18%[2]. In contrast, once initiated, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) does not require regular user input to maintain contraceptive effectiveness. By removing the element of human error, LARC offers one of the most effective contraception methods, with contraceptive failure rates under 1% in the first year of use[2–4]. LARC is convenient — it provides ‘fit and forget’ contraception and has fewer associated health risks than oestrogen-containing combined contraceptives[5].

Individual contraceptive prescribing decisions must also consider acceptability of the contraceptive to the user, as this can determine continuation and the patient’s ability to use it correctly, as well as their medical eligibility for the method and any relevant drug interactions.

The NHS provides LARC without cost to the user from sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, GP practices and maternity, gynaecology and abortion care services after pregnancy. NHS data indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted provision of contraception, including LARC. Data released by NHS Digital show a 37% fall in contraception-related contacts with SRH services in April–September 2020 compared with April–September 2019[6]. Data are not yet available to inform the effect of this disruption on contraceptive use and unplanned pregnancy.

Community pharmacists are not currently LARC providers but can advocate for the use of effective contraception during consultations and in routine interactions with patients. This article outlines information on LARC options available that pharmacists can recommend and how to conduct appropriate consultations.

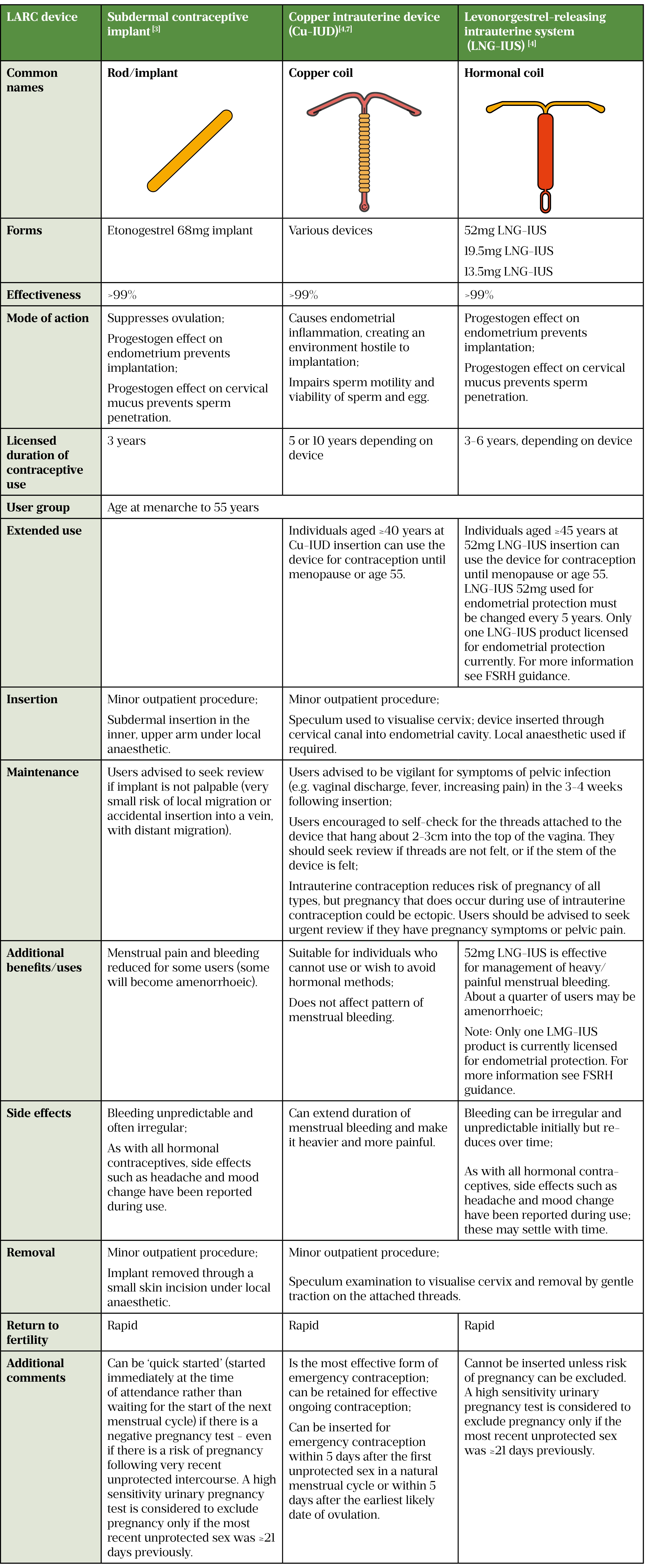

Long-acting reversible contraceptive devices

The LARC methods currently available are the etonogestrel subdermal implant, copper intrauterine device and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Information about these devices can be found in the table below.

The progestogen-only contraceptive depot injection (intramuscular or subcutaneous medroxyprogesterone acetate) is sometimes considered to be a LARC method because it does not require daily or weekly administration. Repeated every 13 weeks (users can be taught to self-administer subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate at home), perfectly used injectables provide >99% effective contraception by suppressing ovulation[8]. However, unlike the LARC methods in the table above, they remain dependent on the user — with typical use, non-compliance results in an estimated first year contraceptive failure rate of around 6%[2]. The bleeding pattern can initially be erratic, but bleeding reduces over time and some users achieve amenorrhoea. Injectables can cause weight gain and are associated with reduced bone mineral density, therefore are not first-line options for adolescents and women aged over 50 years[8]. Return to fertility can be delayed by a year or more after the last injection, making them unsuitable for use by individuals who want to conceive in the near future[8].

LARC methods all offer highly effective, user-independent contraception. A person’s choice of method may depend on the procedure required for insertion/removal, the effect on menstrual bleeding, the patient’s familiarity with the method and past experience of contraception (as well as the experiences of their family and friends). If LARC is not ideally acceptable to an individual, they may discontinue use; if they prefer a short-acting contraceptive and are confident that they can use it reliably, that may be a better option for them.

Contraindications

The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria (UKMEC) details suitability of each contraceptive method, factoring in personal characteristics and common medical conditions[9]. There are relatively few medical contraindications to LARC, which can be used by individuals with characteristics (e.g. older age, smoking, very recent pregnancy) and medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, obesity, migraine with aura) that contraindicate use of oestrogen-containing combined hormonal contraceptives[9]. Any identified medical conditions should be checked against UKMEC. UKMEC indicates, for example, that breast cancer, stroke or heart attack during previous use of the method, and severe decompensated liver disease or hepatic adenocarcinoma, generally contraindicate use of hormonal LARC methods; childbirth in the past four weeks, pelvic infection and distortion of the uterine cavity contraindicate use of intrauterine methods[9]. It should be noted that the UKMEC list is not exhaustive and the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) for each LARC should be referred to for information on potential drug interactions.

As with combined hormonal contraceptives and the progestogen-only pill, contraceptive effectiveness of the etonogestrel implant can be reduced by cytochrome P450 enzyme inducers (e.g. carbamazepine and rifampicin), which reduce systemic exposure to etonogestrel. The contraceptive effectiveness of the LNG-IUS, due to its local intrauterine hormonal activity, the non-hormonal Cu-IUD and the high-dose progestogen depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection are not affected by hepatic enzyme induction. Contraceptive progestogen started within five days after use of ulipristal acetate oral emergency contraception could reduce its effectiveness as emergency contraception[10,11].

Busting long-acting reversible contraception myths and misconceptions

Myths and misconceptions surrounding contraception can be barriers to starting any contraceptive, and are particularly relevant to LARC methods, which are newer and patients can be unfamiliar with. Strongly held but inaccurate beliefs can be difficult to challenge if healthcare professionals are uncertain themselves. Box 1 provides some facts in response to myths that may commonly arise in practice.

Box 1: Myths and misconceptions

MYTH: I need to wait for my period before I can start LARC.

FACT: The implant can be quick-started at any time. The Cu-IUD can be inserted after unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy and the LNG-IUS can be inserted at any time if there is no risk of pregnancy[3,4].

MYTH: I can’t have a coil if I haven’t had a baby.

FACT: Intrauterine contraception can be inserted at any age, regardless of parity[3].

MYTH: The implant will make me gain weight.

FACT: Some people do report weight gain during use of any contraceptive method, but only the injection has been shown to cause weight gain (in some users)[12].

MYTH: LARC could affect my future fertility.

FACT: In clinical studies, none of the LARC methods have been shown to affect long-term fertility or pregnancy outcomes (the injection may delay return to fertility)[8].

MYTH: I’ve just had a baby — I can’t get pregnant again.

FACT: You can get pregnant again as early as three weeks following childbirth. It is recommended that people wait at least 12 months before conceiving again to maximise chances of a healthy pregnancy. LARC can be started immediately after delivery[13].

The role of the pharmacist

While pharmacists are not LARC providers, they will encounter situations where it is appropriate to advocate LARC use for patients. Box 2 outlines important questions that must be considered/discussed when approaching these consultations. Boxes 3, 4 and 5 provide suggestions for situation-specific dialogue.

Box 2: Suggested pharmacist contraception consultation template

Always respect patients’ need for confidentiality (i.e. use of consultation room is essential).

Is there an existing risk of pregnancy?

- Assess requirement for emergency contraception (EC);

- Refer for emergency copper IUD if appropriate;

- Supply oral EC if copper IUD not appropriate/not accepted;

- Advise about pregnancy risk from further unprotected sex;

- Advise about follow up pregnancy testing.

Are there any safeguarding issues?

- Consider signs of physical, sexual and emotional harm, including coercion and/or exploitation.

Does the individual need/want ongoing contraception?

- Are they using contraception — if so, what, and are they using it effectively?

- Do they have any ideas about contraception they would like (or not like) to use?

- Would they like to discuss their contraceptive options?

What contraception would be effective for this individual?

- Give information about contraceptive effectiveness: contrast perfect and typical use effectiveness of condoms, short-acting contraceptives and LARC;

- Do they take any drugs that are potentially teratogenic? If yes, LARC methods should be recommended;

- Do they take any drugs that could reduce contraceptive effectiveness?

What contraception is medically suitable for this individual?

- Do they have any medical condition that would contraindicate any contraceptive method?

- Do they have heavy or painful bleeding that would make use of a copper IUD less suitable?

- Do they take any drugs that could be affected by the contraceptive?

Based on patient responses and to address any specific patient concerns:

- Give specific information about LARC — insertion and removal procedure, duration of use, non-contraceptive benefits, bleeding pattern, side effects and return to fertility;

- Give specific information about short-acting contraceptives.

Signpost to patient information resources.

Facilitate access to local contraceptive services.

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[14]

A request to a pharmacist for oral emergency contraception is an example of an important opportunity for promotion of, and signposting to, effective contraception, including (but not limited to) LARC. After oral emergency contraception, an individual remains at risk of pregnancy from subsequent unprotected intercourse. Intervention by a pharmacist in this situation to support provision of a Cu-IUD, the most effective method of emergency contraception that also offers effective ongoing LARC, or to facilitate ‘quick start’ initiation of suitable hormonal contraception by signposting directly to SRH or primary care contraceptive services, could be essential to preventing unplanned pregnancy. It is essential that pharmacists can provide up to date information to facilitate access to local contraceptive services. An example consultation for emergency contraception is shown in Box 3.

Box 3: Emergency contraception scenario

A patient aged 31 years presents to their local pharmacy seeking emergency contraception.

Pharmacist: “We will give you the morning after pill today, but it is important that you know that it might not work to prevent pregnancy because it is likely that you have already ovulated. We would advise that the most effective emergency contraception is the copper IUD. It is more than 99% effective and can work at times like this, when the morning after pill does not. The copper IUD can also be kept to give you effective contraception going forward — though you can have it taken out at any time.”

Patient: “I don’t like the thought of having a coil.”

Pharmacist: “Would you like me to explain a bit about what the IUD is like, how it works, and how it is put in and taken out?”

Patient: “No, I definitely don’t want a coil.”

Pharmacist: “OK, I understand. There are other effective contraception methods that can be started after the morning after pill to prevent pregnancy in the future. If you use condoms or a contraceptive pill, you are at risk of a pregnancy if you don’t use your contraception absolutely perfectly. But with some types of contraception, such as the implant or the injection, you don’t need to remember to take them every day or every week, and it is less likely that a mistake could put you at risk of pregnancy. All these kinds of contraception methods are available for free at the local sexual health clinic. I can provide you with details about the types of contraception and how to get them if you’d like?”

With the introduction of the desogestrel progestogen-only pill as a pharmacy medicine, it is important that pharmacists make patients aware of the more effective LARC and how to access it[15,16]. Oral contraception can be used as a bridging contraceptive while the user considers and accesses LARC. An example of how this might be discussed in practice is provided in Box 4.

Box 4: Pharmacy progestogen-only pill scenario

A patient aged 27 years with no medical contraindications presents to their local pharmacy to buy the desogestrel progestogen-only pill.

Pharmacist: “You don’t have any medical reason not to use the desogestrel progestogen-only pill and you aren’t taking any medicines that might stop it working. I can sell you a three-month supply to start today. If you take your pill every day, exactly as directed, it is around 99% effective, but it’s really important you know that if there is an error when taking it you could be at risk of pregnancy. People do miss pills or are sick after taking them; about 9 out of 100 pill users might get pregnant in the first year of use.

There are other forms of contraception that you don’t have to remember to take, making them more effective. “For example, you could have a small implant in your arm that gives you a very similar hormone to this pill continuously for three years. The implant is easy and quick to put in, and it’s free on the NHS. If you want to stop using the implant, you can take it out at any time and your fertility comes back quickly. Would you like to discuss the implant or the other forms of contraception that you don’t need to remember to take?”

Patient: “I really want to start contraception now. I’ll just take the pills. I quite like the idea of the implant though.”

Pharmacist: “That’s fine. Use the pills for now and think about booking an appointment to have an implant put in before the pills run out. Shall I give you some information about the implant and where to get it?”

A pharmacist dispensing a teratogenic drug, such as sodium valproate or isotretinoin, has a crucial opportunity to ensure that the individual is on a pregnancy prevention programme to minimise risk of foetal exposure[17]. An example for how this can be managed in practice is shown in Box 5.

Box 5: Teratogen scenario

A patient aged 19 years with epilepsy is collecting their prescription for sodium valproate.

Example dialogue:

Pharmacist: “The sodium valproate medication that you are taking can cause severe harm to developing babies. Can I ask about your current contraceptive plan?”

Patient: “I am not currently using any contraceptives.”

Pharmacist: “Anyone using this medication is strongly advised to be using the most effective contraception. In particular, we recommend LARC, such as the implant or a coil. I can provide you with details of the local sexual health clinic who provide these methods if you’d like?”

To find local sexual health services, visit the NHS website.

Source: FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit [18]

COVID-19 pandemic: effects on contraceptive provision

Extended use of some LARC methods was temporarily recommended when risk of COVID-19 transmission was highest to avoid risk of transmission during face-to-face medical procedures. One year or more of extended use was recommended for devices with evidence of low risk of pregnancy during that extension[19]. Users were advised that contraceptive effectiveness could be lower than during the licensed duration of use and could opt to use a progestogen-only pill or condoms in addition[19].

COVID-19 has disrupted LARC provision, but this period has seen great innovation in telemedicine. For service users, this means that discussion regarding contraceptive choices and information-giving can often now be achieved remotely, with clinic attendance only required for a LARC procedure itself, or for blood pressure measurement ahead of combined hormonal contraception provision. Many services have established free remote provision of the progestogen-only pill[20].

Useful resources

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) clinical guidelines on contraception and links to training resources including a free two-hour online contraceptive counselling course are available on the FSRH website;

- FPA — the sexual health company (previously the Family Planning Association) provides useful patient information on each of the contraceptive methods, including LARC;

- Additional patient resources are available on the NHS website and the Contraception Choices website.

Supported content

Bayer PLC commissioned and funded this article. The company has reviewed the article to ensure factual accuracy in relation to compliance with industry guidelines.

PP-PF-WHC-IUS-GB-0006 / August 2021

- 1Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. World Health Organization: Department of Making Pregnancy Safer & Department of Reproductive Health and Research. 2005.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69855/WHO_RHR_07.1_eng.pdf;jsessionid=1D940075E53146EE1272520A59DF7E25?sequence=1 (accessed Sep 2021).

- 2Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021

- 3FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FSRH Clinical Guideline: Intrauterine Contraception. 2015.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceuguidanceintrauterinecontraception/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 4FSRH Clinical Guideline: Progestogen-only Implant. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2021.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-implants-feb-2014/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 5FSRH Clinical Guideline: Combined Hormonal Contraception. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2019.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/combined-hormonal-contraception/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 6Sexual and Reproductive Health Services, England (Contraception) April – September 2020 (provisional statistics). NHS Digital. 2021.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/sexual-and-reproductive-health-services/april-to-september-2020 (accessed Sep 2021).

- 7FSRH Clinical Guideline: Emergency Contraception. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2017.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 8FSRH Clinical Guideline: Progestogen-only Injectable. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2014.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-injectables-dec-2014/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 9UK Medical Eligibility Criteria. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2016.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/uk-medical-eligibility-criteria-for-contraceptive-use-ukmec/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 10Drug interactions. British National Formulary. 2021.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/interaction/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 11FSRH CEU Guidance: Drug Interactions with Hormonal Contraception. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2017.https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 12FSRH Clinical Statement: Contraception and Weight Gain. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2019.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/fsrh-ceu-statement-contraception-and-weight-gain-august-2019/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 13FSRH Clinical Guideline: Contraception After Pregnancy. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2017.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/contraception-after-pregnancy-guideline-january-2017/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 14Contraception — assessment. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/contraception-assessment/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 15Lovima public assessment report. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/lovima-75-microgram-film-coated-tablets-desogestrel-public-consultation/outcome/lovima-public-assessment-report#conclusion (accessed Sep 2021).

- 16A public consultation on reclassifying two medicines containing desogestrel from prescription only (POM) to pharmacy (P). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/hana-75-microgram-film-coated-tablets-desogestrel-public-consultation/public-feedback/a-public-consultation-on-reclassifying-two-medicines-containing-desogestrel-from-prescription-only-pom-to-pharmacy-p (accessed Sep 2021).

- 17Information on the risks of Valproate use in girls (of any age) and women of childbearing potential (Epilim, Depakote, Convulex, Episenta, Epival, Kentlim, Orlept, Sodium Valproate, Syonell, Valpal, Belvo & Dyzantil). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2020.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950802/107995_Valproate_HCP_Booklet_DR15_v07_DS_07-01-2021.pdf (accessed Sep 2021).

- 18FSRH CEU Statement: Contraception for women using known teratogenic drugs or drugs with potential teratogenic effects (February 2018). FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2018.https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/fsrh-ceu-statement-contraception-for-women-using-known/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 19FSRH CEU recommendation on extended use of the etonogestrel implant and 52mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system during COVID restrictions. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. 2020.https://www.fsrh.org/documents/fsrh-ceu-recommendation-on-extended-use-of-the-etonogestrel/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 20FSRH statement: Provision of contraception during the COVID-19 pandemic. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 2020.https://www.fsrh.org/documents/fsrh-guidance-contraceptive-provision-changes-covid-lockdown/ (accessed Sep 2021).