Iqoncept/Dreamstime.com

This content was published in 2011. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Mentoring is a one-to-one relationship of professional development, usually between someone seeking professional progression and a more experienced practitioner. This could also include someone seeking to develop new expertise and a practitioner already active in that area.

Mentoring is different from coaching in that mentoring is concerned with professional development, rather than learning specific skills but many commentators argue that there is considerable crossover between the two.

Mentoring has been shown to have a positive impact on career development in healthcare, helping to improve confidence and interpersonal skills of mentors as well as mentees. It also improves career retention rates and work performance. Moreover, work among psychiatrists showed that mentoring greatly benefited professionals who worked in multidisciplinary teams or who were isolated from their peers in daily practice.1

Who might need a mentor?

Although mentoring can be beneficial at any time during a pharmacist’s professional life, it is especially helpful at significant stages of career development, for example:

- In the early years of practice

- On moving to a different sector of practice or practice environment

- If seeking to gain experience in advanced or specialist practice areas

- On returning to practice after a career break

Many community and locum pharmacists work in isolated circumstances and mentoring also has the potential to support these people, for example, it could give them the confidence needed to develop new clinically focused pharmacy services.

Mentoring could also help pharmacists with performance difficulties, but its exact role here will depend on the stance taken by the General Pharmaceutical Council and the National Clinical Assessment Service on the cases they deal with.

It should be stressed that professional mentoring in pharmacy should be seen as a positive and affirming experience for both mentors and mentees to support development and advancement in the profession.

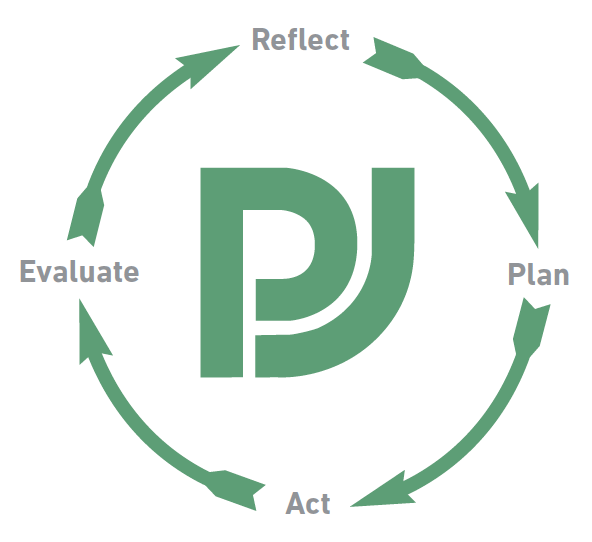

Reflect

- What are the benefits of mentoring and at what stages of professional life can mentoring be helpful?

- What can you do to ensure a successful mentoring relationship and what problems can you look out for?

- What resources are available to support mentors and mentees?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better.

Finding a mentor

Mentoring is an intentional relationship. Even if a mentee is not matched with a mentor through a formal scheme, the mentee will typically approach a potential mentor in order to initiate a relationship, the goal of which is professional development. However, a mentor should not be the mentee’s educational tutor. Nor should mentors be part of any formal assessment or supervision process that a mentee might be involved in.

A number of mentoring schemes havebeen set up specifically for pharmacists. They include:

- The Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists(GHP)/United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association (UKCPA) Pharmentor Scheme (www.pharmentor.nhs.uk)

- The National Association of Women Pharmacists mentoring scheme (www.nawp.org.uk)

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society is in the process of establishing a mentoring scheme for its members. It is to be hoped that this scheme will provide a network of mentors across different sectors of the pharmacy, and a cohesive ethos of mentoring across the profession.

An organised mentoring scheme might have an adjudication or moderation system, which will help to resolve any problems in the mentoring relationship should they arise. If a mentee seeks a mentor independently, then the mentee and mentor take sole responsibility for the conduct of the relationship.

Reflection is important

It is likely that a specific career need or issue will be the trigger for a pharmacist to seek a mentor. Pharmacists should reflect on their professional development objectives so that they can be clear about their professional goals and expectations of a mentoring relationship before seeking a mentor. This will help them to identify the most appropriate potential mentors. Helpful questions to ask are listed in Panel 1.

Panel 1: Questions for prospective mentees

- Where am I now in my life and career?

- How did I get here? (What significant professional experience do I have and what have been my most notable achievements?)

- What is working well for me?

- What challenges or difficulties do I face?

- What are my strengths and weaknesses?

- How might a mentoring relationship help with my strengths and weaknesses?

- Where do I want to be in one, three and five years’ time?

- What might I need to change or to develop in order to get there?

- What do I want from the mentor and the mentoring relationship?

Those who offer their time as mentors should also reflect on their skills and experience. As well as past professional development, future development should be considered because mentoring can often influence this. Potential mentors should be honest about their skills and experience, and should be clear about the sort of people they could mentor. Helpful questions for potential mentors to ask themselves are listed in Panel 2.

Panel 2: Questions for prospective mentors

- Where am I now in my life and career?

- How did I get here? (What significant professional experience could I offer to a mentee?)

- How well do I know my strengths and weaknesses, and how have I managed them in the course of my career?

- What am I trying to achieve in my career at present? How might this benefit a mentee?

- Do I have the interpersonal and communication skills to facilitate a mentoring relationship?

- What will I learn from being a mentor?

- What sort of person could I mentor (ie, role, stage in career, specialty, etc)?

Attributes required

A good mentor is:

- Available

- Approachable and personable

- Committed to the mentoring process

- A good listener

- Able to empathise with the mentee

- Perceptive

- Non-judgemental

- Honest

- Objective

- Able to challenge the mentee

- Encouraging and motivating

Although this list provides a range of the important qualities, it is by no means exhaustive. The mentee should not be a passive player in the mentoring process. For mentoring to benefit the mentee fully, he or she should be:

- Committed to the mentoring process

- Motivated

- Prepared to listen to and engage with advice or critique

- Prepared to put in the work

- Receptive to challenges

- Realistic about the mentoring relationship and what it can offer

Training for mentors

Various courses are available for developing mentoring skills or training to be a mentor. Some of these are occupational schemes for health professionals, others are for the business community in general and still others provide mentoring skills training as part of personal development.

Due to the range of available training programmes, it may be helpful to evaluate courses according to the competencies that they help to develop. Mentor training should cover the following elements:

- The nature of mentoring and types of mentoring

- Relationship styles and expectations

- Ground rules of mentoring relationships

- Conducting mentoring relationships

- Ethical issues associated with mentoring

In addition, government competences (National Occupational Standards for Learning and Development) for mentoring in the workplace are available (see Resources).

How to start a mentoring relationship

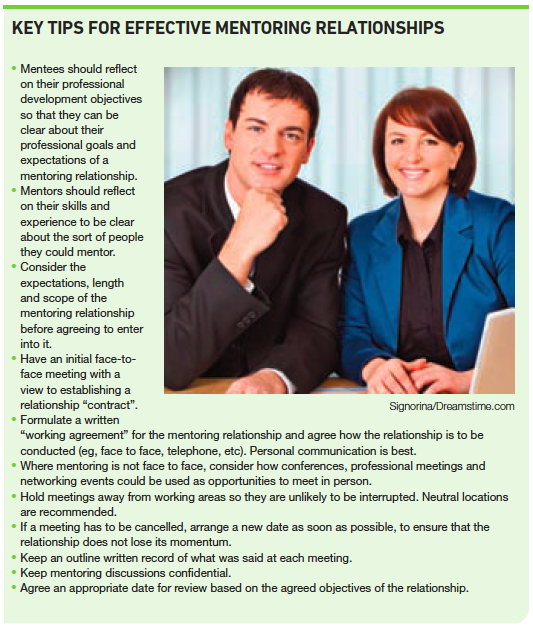

Both parties need to consider the expectations, length and scope of the mentoring relationship before agreeing to enter into it. A potential mentee and mentor should have an initial meeting in order to discuss these issues with a view to establishing a “contract”, as in a therapeutic relationship (eg, between a counsellor and a client). This meeting should be face to face where possible.

Expectations

Although mentees should have an understanding of their objectives and, therefore, their expectations of the mentoring relationship at the initial meeting, potential mentors might still need to spend some time exploring mentees’ aspirations to help them to clarify their objectives.

Mentors and mentees should also discuss whether they expect the mentoring relationship to be directive (where the mentor steers the mentee clearly in their professional practice) or non-directive (where the mentor will help the mentee to develop their own approach). This process of discernment is important because when objectives and expectations of the relationship are clearly expressed and understood the mentoring relationship is more likely to be successful and mutually fulfilling.

Length of the relationship

The length of a mentoring relationship will be, to some extent, determined by the mentee’s objectives. Pharmacists who are seeking to return to practice might need a mentor to meet with frequently for a relatively short period (eg, three to six months) to reflect on issues they face in their new working situation, until they have settled in. In contrast, hospital pharmacists who are seeking to gain qualifications in a clinical specialty and to reflect on their practice as they gain experience may need a mentoring relationship that lasts for two years or more, but with less frequent meetings.

With long-term mentoring relationships, however, it is likely that the objectives and expectations of the relationship might change over time, and these should be regularly reviewed.

Scope

The scope of the mentoring relationship will be determined by how clearly the objectives and expectations of the mentoring relationship have been defined. As a result, it should be possible to identify issues that will be outside the scope of the mentoring relationship. It is important to do this because the mentor may not be the best person to help the mentee with issues beyond the agreed scope of the relationship. For example, it might be agreed that the mentoring relationship will focus on clinical practice but not on business skills. Mentors might need to signpost mentees to alternative sources of support in areas outside of the scope of their objectives.

The mentoring relationship might also uncover issues concerning the mentee’s personal development, which would be outside the remit of professional mentoring. Again, the onus would be on the mentor to signpost the mentee to suitable support agencies. Nevertheless, the scope of the mentoring relationship can be a grey area. For example, family circumstances often impinge on the working situation and, while one mentee might feel happy with discussing them in the mentoring relationship, as far as they affect the workplace, another mentee might not.

As well as considering the mentoring “contract”, the initial meeting provides an opportunity for the mentor and mentee to get to know each other, and determine whether they can work together, in terms of personalities and how they will relate to each other. After the initial meeting there should be no obligation for the mentor or mentee to embark on the relationship if either party feels that it would not work. However, if either party chooses not to continue with the mentoring relationship, they should be clear and honest about the reason.

It is often beneficial for the mentor and mentee to formulate a written “working agreement” for their mentoring relationship, based on the discussion at their initial meeting. (see GHP/UKCPA resources for an example template).

Conducting the relationship

If the two parties agree to a mentoring relationship, they should also agree how their relationship is to be conducted. They should choose a suitable method of communication, subject to any geographical or operational constraints, but the mentoring relationship is an interpersonal one so personal communication is encouraged: email and instant messaging may be inappropriate. However, the method of mentoring should also suit the dynamics of the relationship and the mentee, mentor or any third party (eg, mentoring scheme)should not be prescriptive about the methods used.

Subsequent mentoring meetings can be face to face, if the mentor is based in the same area as the mentee. Telephone and video conferencing (eg, Skype) may be considered, especially if mentor and mentee are distant geographically. For example, a pharmacist may wish to have a mentor to support development of an innovative area of practice in an area where there are few other practitioners.

If mentoring is conducted by telephone or Skype, participants should consider how they could use conferences, professional meetings and networking events as opportunities to meet in person.

Whichever method is chosen, meetings should be conducted in a private setting where participants will not be overheard. Ideally, it should also be held away from working areas — it is essential that the meeting is not subject to work-related interruptions because an important aspect of the mentoring process is to take a step back from daily working issues in order to reflect on them holistically.

In addition, it is beneficial for the meeting to take place in a location that is neutral territory for both mentor and mentee: the home of either mentee or mentor therefore would not be a suitable venue. An office or dedicated meeting room is an ideal setting.

For community pharmacists, a private location away from the working environment may be hard to find and they might need to consider meeting off the community pharmacy premises or outside working hours.

The frequency and length of meetings should be appropriate for the objectives of the mentoring relationship. In general, meetings should be between one and two hours in length to ensure that important issues are raised and adequately explored.

The mentor and mentee should be clear about their roles and tasks. The mentor’s task is to structure the framework for communication and reflection in the mentoring meeting, and to determine the schedule of meetings. However, the mentee has the responsibility of identifying his or her professional development needs, engaging in the mentoring relationship and doing any preparatory work between meetings. If ameeting has to be cancelled, a new date shouldbe arranged as soon as possible, to ensure thatthe relationship does not lose its momentum.

An outline written record of what was said at each meeting should be kept. The mentor and mentee should agree an appropriate record for each meeting.

Confidentiality

The mentor and mentee should consider the boundaries of confidentiality within the mentoring meeting. Confidentiality of discussions within a mentoring relationship is essential because it allows trust to develop between the two parties and enables both to discuss difficult professional or workplace issues frankly and without fear of recrimination.

Both mentor and mentee also need to consider patient confidentiality within the mentoring relationship. For example, an issue that the mentee is facing may involve a patient who the mentor does not know, and with whom the mentor does not have a legitimate relationship of care. In this situation, the mentee would need to respect the patient’s confidentiality and not disclose any details that might identify the patient. Pharmacists are also reminded that they are bound by professional standards for patient confidentiality.

Review

An appropriate date for review of the mentoring relationship should be agreed between the mentor and mentee, based on the agreed objectives of the mentoring relationship. For example, if a pharmacist is newly qualified and having a monthly mentoring meeting to assist with early years development, it may be appropriate to review the relationship after a year.

At a review meeting, the mentor andmentee may decide:

(a) To continue the mentoring relationship as the objectives agreed initially have still to be achieved;

(b) That the needs of the mentee have now changed and, while the mentor is probably still the best person to help, new objectives and expectations of the mentoring relationship need to be agreed; or

(c) That the mentoring relationship is at an end because either the original objectives have been met or the needs of the mentee have changed, and a new mentor is needed to meet those needs

Helpful tools

There are various tools that might assist in developing the mentoring relationship. Examples include:

- The ABC (aspirations, behaviours, choices) model This helps mentees to identify the behaviours required to achieve their professional development aspirations, and the individual choices that need to be made to reinforce those behaviours. For example, the mentee aspiring to be a manager might wish to develop personal qualities such as confidence, self-motivation, perseverance and ability to cope with criticism. The mentor can then help the mentee to decide what choices to make in work situations in order to reinforce these behaviours.

- Egan’s three-stage model This is a tool for developing mentoring relationships. It involves identifying the objectives at each stage of the mentoring relationship. The model enables the mentor and mentee to establish a framework for the objectives, and helps the mentor to identify the skills (eg listening, problem solving) and tasks needed to achieve those objectives.

- The GROW framework Identifying the Goal, checking the Reality, identifying the Options and engaging the Will. This tool may be used to structure mentoring meetings or relationships. First, the mentor and mentee identify goals of the meeting or relationship, and then check whether those goals are realistic (ie, whether or not they can be achieved, how much control the mentee has, etc). The mentor and mentee then identify the options and methods to achieve the goal, and then a series of actions is agreed upon to help the mentee achieve the goal.

See Resources for further information.

Dealing with problems

Both mentors and mentees should be aware of the potential problems that can occur in the mentoring relationship. These can include ineffective relationships and dependence.

If the mentor is similar in personality and experience to the mentee, the mentoring relationship can be too comfortable. Such a relationship will not progress and help the mentee with professional goals because the mentor will not be in a position to challenge the mentee and the relationship is ineffective. A change of mentor should be considered. However, such a problem is often not apparent to either party and this is where a mentoring scheme might be useful.

Since the mentoring relationship is a personal relationship of professional growth and development, usually between a junior professional and a more experienced, senior colleague, there is the potential for the mentee to become psychologically dependent on the mentor, especially in a relationship that is directive. It is also possible for mentors to become dependent on their relationship with mentees. Dependence limits the potential for professional development for both parties and, as such, is damaging to mentoring relationships. Dependence can be avoided if both parties are aware of the potential, and an overly directive mentoring relationship is avoided.

Occasionally, during the course of amentoring relationship, serious personalproblems affecting either the mentee or thementor can come to light. These might include alcohol or drug problems, misconduct or sexual indiscretion.

If one party has a serious personal issue, the other should not attempt to engage on the issue, but should end the session and advise that the mentoring relationship should be immediately terminated on these grounds. It is reasonable for the other person in the mentoring relationship to signpost the person to any agencies and organisations that may be able to help.

I have already discussed confidentiality. Although the relationship between the mentee and mentor should be private and confidential to enable both parties to be frank about professional issues and workplace problems, there are circumstances where information may need to be disclosed to a third party. These circumstances would include where disclosure is required by statute, where disclosure is necessary to prevent a crime or serious injury or to safeguard a child or vulnerable adult. If one party in the mentoring relationship needs to disclose information to a third party, where possible both parties in the relationship should agree to this.

Conclusion

Mentoring has the potential to enhance professional development in a range of scenarios in pharmacy. The mentoring relationship is also fulfilling for both mentee and mentor. At present, a minority of practising pharmacists have mentors. In future, however, a greater proportion of pharmacists might benefit from having one.

Practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the regulator will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Reflect on your career in pharmacy and identify your future professional aspirations. Would you benefit from mentoring?

- Consider the skills and experience you could offer to a potential mentee. Sign up as a mentor with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (email support@rpharms.com).

Consider making this activity one of your nine CPD entries this year.

Resources

- National Occupational Standards for Learning and Development workforce competence L14 (Support learners by mentoring in the workplace) is available at https://tools.skillsforhealth.org.uk.

- ‘Everyone needs a mentor: fostering talent at work’ by Clutterbuck (London; CIPD: 2001) is a classic textbook on the use of mentoring in the business and professional context, discussing the role and skills of mentors, and issues associated with establishing a professional mentoring service.

- ‘Coaching and mentoring’ by Parsloe and Wray M. (London; Kogan Page: 2000) provides a general overview of coaching and mentoring, bringing examples from sport through to business. It leans more towards coaching than mentoring (see above), but gives many helpful insights.

- Readers can find out more about mentoring tools, such as Egan’s three-stage model, from“Mentoring resources” by the GHP and UKCPA, available at www.pharmentor.nhs.uk. A “Mentoring handbook” containing templates of a mentoring working agreement and a mentoring session record sheet, is available at this site. This online resource also contains advice for mentors and mentees, information on ethics and practical arrangements and other tools to facilitate the listening and reflective processes in mentoring.

References

- Roberts G, Moore B, Coles C. Mentoring for newly-appointed consultant psychiatrists. The Psychiatrist 2002;26:106–9. CPD articles are commissioned by The Journal and are not peer reviewed.