Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Define the term ‘red flag’ and identify red-flag symptoms;

- Discuss the pharmacist’s role in identifying red-flag symptoms;

- Explain the process of escalating and referring a patient, who presents with a red-flag symptom, to an appropriate service;

- Outline a pharmacist’s approach to safety netting and the importance of documentation to prevent patient harm.

Red-flag symptoms are warning signs that indicate a more serious underlying pathology in a patient. The term ‘red flag’ originated in the 1980s and related to back pain[1]. However, the term is now used to encompass signs and symptoms from all body systems that are suggestive of a possible serious illness or disease. Red-flag symptoms can be general (e.g. weight loss or fatigue) or specific (e.g. haemoptysis) and act as an alert of potentially sinister pathology[2]. However, red flags are not diagnostic tests; their main role is that they raise suspicions of a severe underlying cause[3].

Pharmacists must feel confident to identify red-flag symptoms and ensure that the patient is escalated and referred appropriately to reduce the risk of patient harm. This article will offer guidance on how to identify red flags to inform clinical decision making during patient consultations. It will also discuss how to approach referral and use effective safety netting and follow-up to promote patient safety.

Importance of identifying red-flag symptoms

Pharmacists are often the first point of contact for patients and the public, and with the expansion of pharmacist prescribing, advanced services and minor ailment schemes continue to assume greater levels of responsibility within the multidisciplinary team[4]. Patients may present or be referred to a pharmacist with symptoms that require the pharmacist to determine whether they can safely manage the patient or whether the situation needs further investigation and referral. A thorough knowledge of red-flag symptoms is a useful tool.

However, because of the broad range of clinical presentations seen across different sectors and healthcare settings, recognising red flags in clinical practice can be difficult. It requires pharmacists to have a broad knowledge of minor ailments, and acute and chronic diseases, and the ability to differentiate symptoms. Many clinical presentations are benign; however, some presentations could be caused by serious conditions[2]. Asking a patient about red-flag symptoms or identifying these during a clinical examination allows the pharmacist to distinguish between these two situations. Documenting the absence of red-flag symptoms in a patient’s history is as crucial as documenting positive findings.

How to identify red flags

Red flags can be identified from the patient history and the clinical examination. To minimise the risk of missing red flags:

- Ensure that you start with open questions when taking a patient history. Follow up with more specific, closed questions;

- Explore the presenting complaint or reason for the consultation in detail;

- Search for hidden red flags on examination and when questioning the patient;

- Be aware of red flags that, when present in combination, increase the probability of serious pathology (e.g. cough lasting more than three weeks combined with fatigue and unexplained weight loss)[5].

Red flags should be considered within the individual context of the patient. Consider the duration of the symptom, associated features, life course considerations and clinical signs on examination[5]. Some examples of contextual factors include:

- Duration: seemingly harmless symptoms can be red flags if they are of prolonged duration (e.g. cough, fatigue).

- Associated features: consider the context of the red-flag symptom (e.g. chest pain). Where is it located? Is it related to an injury? Chest pain in a young patient localised to the right side after a tae kwon do tournament (likely to be musculoskeletal in nature) is very different to a central, crushing chest tightness radiating to the back and jaw in a male in their 60s (more likely to a myocardial infarction);

- Age: Older adults have a higher incidence of multimorbidity, frailty and problematic polypharmacy. Multimorbidity and frailty are complex syndromes, which can make recognition of red flags and the formulation of a diagnosis more challenging. Frailty syndromes (e.g. immobility, falls, impaired cognition) can mask serious underlying pathology. A change in bowel habit is more likely to indicate severe pathology in a patient in their 60s than in a teenager;

- Clinical examination: consider the presence or absence of positive findings on examination to contextualise the symptoms. For example, a red, swollen bite on the leg of a patient with normal vital signs makes serious underlying infection unlikely[5].

Categorising red-flag symptoms

There are a variety of potential red-flag symptoms. A structured approach to history taking and clinical examination can help clinicians to identify, categorise and differentiate between signs and symptoms that are benign or suggestive of underlying pathology. The categorisation of red flags by body systems or common conditions can support clinicians in their approach (see Figure)[1–4,6].

Why red-flag symptoms are often missed

Red flags can sometimes go unrecognised in clinical practice. Understanding the reasons why they may go undetected can raise awareness for your practice.

Reasons why red flags may go undetected include:

- Not listening to the patient’s presentation of their symptoms;

- Rushing/time constraints;

- A lack of knowledge of the presenting condition;

- A lack of knowledge of red-flag symptoms;

- Failing to refer or reassess the patient if the examination findings and history from the patient do not fit your suspected diagnosis;

- Being influenced by previous similar cases;

- Bias and pattern recognition[7].

There are many types of cognitive bias or errors, and being aware of common errors can help clinicians recognise and avoid them. For example, diagnostic momentum bias: the tendency for a diagnosis to be accepted and passed on without question. This could happen if a patient seems to be presenting with worsening symptoms of a known diagnosis, such as a woman with a history of migraines presenting with a severe headache, mistakenly assumed to be another migraine. The headache was, however, a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Another example is confirmation bias: when a clinician selectively accepts clinical data to support a desired diagnosis and ignores results that do not support this — for example, an older, confused female patient had a positive urine dipstick test for nitrates with new incontinence, and the clinician assumed a urinary tract infection and prescribed antibiotics. However, the patient was apyrexial, showed no signs of sepsis, white cell count and C-reactive protein results were in normal range and the urine culture showed no growth. The correct diagnosis was urinary retention secondary to constipation. No infection was present and the patient should not have been prescribed antibiotics.

Minimising cognitive errors

To reduce the risk of cognitive errors, clinicians should develop their clinical reasoning skills and, following completion of a patient history and clinical examination, reflect on their findings. Ask the following questions:

- If it is NOT the working diagnosis, what else could this be?

- Are there any red flags? What is the most sinister possibility?

- Is there any evidence that does not support the working diagnosis?

Asking these questions may help you to identify where further information needs to be gathered or discussed. Learning from incidents and understanding internal and external factors that can influence your individual biases (clinical knowledge, experience, fatigue, workload, team pressures) may help to reduce them.

Process of escalation

Once a red flag has been identified during a patient assessment, it is important to follow appropriate escalation procedures to ensure prompt referral. Referral pathways will vary depending upon the sector of practice in which you are working.

In community pharmacy, referral is most commonly to general practice. However, refer to A&E (or call 999) for patients who are at risk of a serious illness or rapid deterioration. The NHS England Pharmacy First clinical pathways state clear referral criteria for seven common conditions (acute otitis media, impetigo, infected insect bites, shingles, sinusitis, sore throat and uncomplicated urinary tract infection)[5]. Each pathway initially asks you to consider the risk of deterioration and serious illness, and a flow diagram lists the signs and symptoms of more serious conditions. In most instances, it recommends a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) is calculated before signposting the patient to A&E or calling 999. If the patient is assessed as not being at risk of deterioration or serious illness, the next step in the flowchart can be considered. Within the pathways, there are also specific criteria for when an onward referral should be made.

In primary care, red flags will often lead to an urgent or immediate referral to secondary care for further investigations or treatment. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has produced guideline referral timelines for certain suspected cancers[8]. These guidelines make recommendations on the symptoms and signs, classified according to site, symptoms and investigation results, and the referrals are classified as immediate (within a few hours), very urgent (within 24 hours), urgent (within 2 weeks) and non urgent[8].

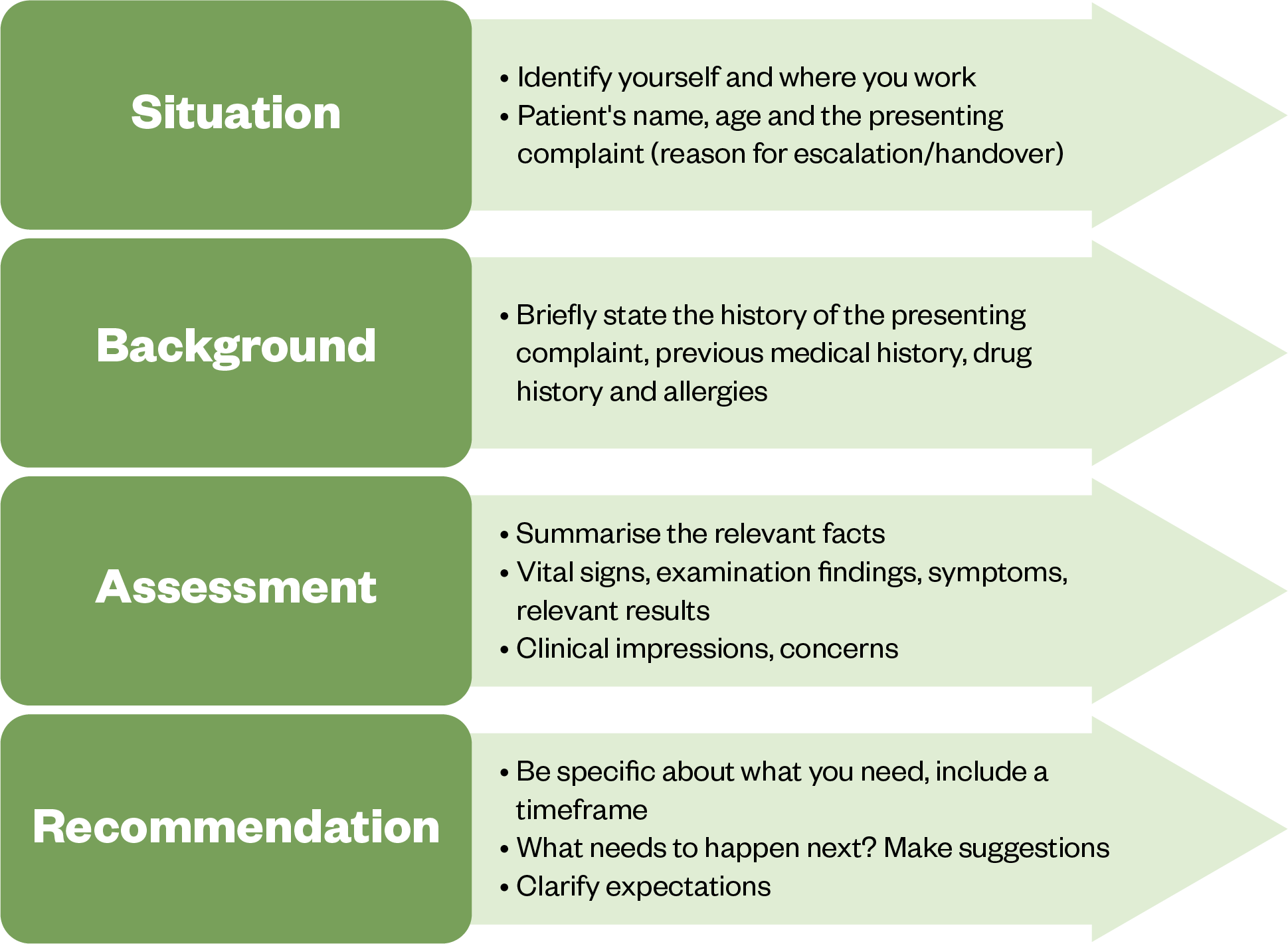

In secondary care, referral is often to another team within the hospital or to a more senior clinician (i.e. specialist registrar). Regardless of sector, the referral process always requires handing over patient care to another healthcare professional. When handing over the responsibility of patient care, full and effective communication is essential. The SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) communication tool can help this process, as it helps structure handovers so that all vital information is captured (see Figure 2). SBAR can also be used to escalate a clinical issue that requires urgent attention[9].

NHS: The Handbook of Quality and Service Improvement Tools

There is moderate evidence for improved patient safety with the use of the SBAR tool, especially when used to structure a handover taking place over the phone[9]. The SBAR tool is predominantly used in secondary care, but it is a useful tool to shape communication at any stage of the patient’s journey, such as when making GP referrals from community pharmacy, referring to secondary care or communicating discharge information from secondary care to primary care[9].

Safety netting and documentation

Safety netting involves providing patients with information about what to expect after the consultation, including what to do should their symptoms not improve within a specific timeframe, or if they get worse. Red flags should be discussed with patients, with instructions on when and how to seek further medical attention should they occur. The NHS England Pharmacy First clinical pathways offer safety-netting advice for the seven clinical conditions mentioned earlier[5]. Guidance on providing safety netting during patient consultations can be found in the Box.

Box: Recommendations on safety-netting advice

- Integrate safety netting throughout the entire consultation — it should not be hurried at the end;

- Use simple terms and avoid jargon and abbreviations — customise advice and alleviate potential sources of anxiety;

- Organise information into manageable chunks to aid the patient’s retention of advice;

- Encourage patients to express their expectations and concerns and address these in the safety-netting plan.

The safety-netting plan

- Clarify and discuss any uncertainties regarding the patient’s condition and the follow-up plan;

- Provide an initial diagnosis, explain the expected duration of symptoms (or how they might change), offer practical advice for self-care and symptom management to empower patients and provide clear instructions for when they should seek further medical attention;

- Personalise someone’s risk based on their characteristics and not on population data. The plan should be personalised and address factors that could impact the individual’s adherence to advice;

- Allow the patient to ask questions and to participate in decision making regarding their care;

- Actively check the patient’s understanding. Recognise the patient’s ability to assess their own health and acknowledge their autonomy to modify the plan if needed[11].

It is a professional and legal requirement to make appropriate, detailed, contemporaneous patient notes [12,13]. However, it has been reported that safety-netting advice is inconsistently documented in medical records[11]. Documentation should include the patient details, history, results of investigations and examinations, consent obtained, diagnosis and decisions made, including rationale and any advice given, which includes safety-netting advice. Appropriate documentation informs other healthcare professionals of what care was given to the patient and its rationale, and is therefore essential for continuity of care. The maxim ‘if it’s not written down; it didn’t happen’ serves as a useful reminder that medical records are legal documents and the evidential starting point in any medical negligence claim[14].

The following case studies provide an opportunity to apply some of the principles introduced in this article to practice.

Case study 1: A young child with ear pain

A girl, aged three years, attends the community pharmacy with her mother. Her mother reports that she has had severe left-sided ear pain for the past 24 hours. She said she has noticed her tugging at her left ear, and she has been crying throughout the day with pain. She was unable to sleep last night. Her mother has given her paracetamol, which has provided some relief. She is tired and irritable. Her mother took her temperature this morning, which was 38oC.

Upon questioning, you find that the child has a history of recurrent ear infections (when she was aged one year), which were treated with antibiotics. She has had two ear infections in the past year and her last infection was three months ago. She is up to date with her childhood immunisations and there is no family history of ear disorders or chronic illnesses.

The mother reported that her daughter has had no headaches, photophobia, muscle weakness, rashes or recent upper respiratory tract infections.

The child lives with both parents and her brother, who is aged six years. She attends the local nursery when her parents are both at work.

On examination, inspection of the left ear reveals erythema and mild oedema of the external auditory canal. The tympanic membrane appears red and bulging. There is tenderness upon manipulation of the tragus and behind the ear. There is also erythema behind the ear. No otorrhoea or tympanic perforation is seen. The right ear appears normal.

What should the pharmacist do?

This patient has red-flag symptoms that could indicate mastoiditis: fever, redness and tenderness behind the ear. She should be referred to A&E.

The pharmacist provides a letter for the patient to take to A&E to summarise their findings. What should be included in this letter?

Situation:

The pharmacist’s name and profession. The patient’s name, age and that they were assessed in the community pharmacy after presenting with earache in her right ear.

Background

The child has a history of recurrent ear infections when she was aged one year. Her last ear infection was 3 months ago, and she has had two in the past 12 months. She has a temperature of 38oC and is tired and irritable.

Assessment

On examination, the tympanic membrane was red and bulging and there was erythema and mild oedema seen in the external auditory canal. There was also tenderness and erythema behind the left ear. The pharmacist is concerned that she is showing signs of mastoiditis.

Recommendation

The child needs to be assessed immediately.

Case study 2: An older man with abdominal and back pain

A man, aged 67 years, presented to ambulatory emergency care (AEC) with abdominal pain and lower back pain. The patient was asked about associated gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, change in bowel habit, haematemesis, melaena, location of the pain, severity, weight loss and fever. The patient denied any associated GI symptoms except pain across the abdomen and lower back, rating the severity of the pain as 7/10. The patient had a history of hypertension and was taking losartan, and had been commenced on a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug by his GP for his lower back pain two days ago.

A NEWS2 assessment revealed that the patient was hypotensive (106/59mmHg) and had a significant postural drop and tachycardia (heart rate: 110bpm), which was thought to be secondary to pain and low blood pressure. When asked if he felt dizzy, the patient reported feeling faint on standing and was advised to stop his losartan because of the hypotension. The pharmacist discussed the patient with the GP in AEC and they agreed a plan to test urine, urea, electrolyte panel, full blood count and C-reactive protein to explore the differential diagnoses of a urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis or kidney stones.

What should the pharmacist do?

The patient was admitted to the acute medical unit and examined by an advanced clinical practice pharmacist. They noted that the patient was in significant pain and, on examination, had a tense abdomen, and his full blood count showed a significant drop in haemoglobin to 52g/L (normal range is 135–180g/L). The pharmacist immediately referred the patient to the on-call registrar for suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm based on the observed factors (age >65 years, abdominal pain, lower back pain, dizziness, hypotension and drop in haemoglobin). The patient was reviewed immediately, sent for an urgent CT scan of their abdomen and rushed to vascular surgery for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The importance of heeding red-flag symptoms

In this case, the combination of red-flag symptoms (sudden severe abdominal pain radiating to back, dizziness and hypotension) should have alerted the AEC clinician to the possibility of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, the hypotension was linked to medication and the abdominal and back pain to possible infection. This case highlights the importance of considering the context of red flags and the importance of red-flag symptoms in combination.

Conclusion

Red-flag symptoms serve as crucial warning signs that can indicate potentially severe underlying medical conditions across bodily systems. Pharmacists, often the first point of contact for patients, play a vital role in identifying these red flags, ensuring appropriate patient escalation and referral. Effective identification involves thorough patient history taking and examination, considering factors such as duration, associated features and clinical signs. Escalation requires clear communication and referral to appropriate healthcare professionals. Safety netting, integral to patient consultations, involves providing guidance on symptom progression and when to seek further medical attention. Consistent documentation of safety-netting advice and other pertinent details in medical records is essential for legal and professional accountability, ensuring continuity of care and mitigating potential medical negligence claims. Recognising and addressing red-flag symptoms is vital for timely intervention and optimal patient outcomes.

- 1Welch E. Red flags in medical practice. Clin Med. 2011;11:251–3. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-251

- 2C. Ramanayake RPJ, K. Basnayake BMT. Evaluation of red flags minimizes missing serious diseases in primary care. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:315. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_510_15

- 3Red flags. Healthcare Improvement Scotland. 2023. https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/ggc-msk-index-in-development/red-flags (accessed March 2024)

- 4NHS Long Term Plan. NHS. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed March 2024)

- 5Schroeder K, Chan W-S, Fahey T. Recognizing Red Flags in General Practice. InnovAiT. 2011;4:171–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/innovait/inq143

- 6Launch of NHS Pharmacy First advanced service. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/launch-of-nhs-pharmacy-first-advanced-service/ (accessed March 2024)

- 7Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1860–b1860. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b1860

- 8Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12 (accessed March 2024)

- 9Müller M, Jürgens J, Redaèlli M, et al. Impact of the communication and patient hand-off tool SBAR on patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022202. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022202

- 10The Handbook of Quality and Service Improvement Tools. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2010. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/the_handbook_of_quality_and_service_improvement_tools_2010-2.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 11Friedemann Smith C, Lunn H, Wong G, et al. Optimising GPs’ communication of advice to facilitate patients’ self-care and prompt follow-up when the diagnosis is uncertain: a realist review of ‘safety-netting’ in primary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:541–54. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014529

- 12Standards for pharmacy professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2017. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/standards/standards-for-pharmacy-professionals (accessed March 2024)

- 13Records Management Code of Practice: A Guide to the Management of Health and Care Records. NHS England. 2023. https://transform.england.nhs.uk/documents/165/NHSE_Records_Management_CoP_2023_V5.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 14Andrews A, St. Aubyn B. ‘If it’s not written down; it didn’t happen…’ Journal of Community Nursing. 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297922054_’If_it’s_not_written_down_It_didn’t_happen’ (accessed March 2024)

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

excellent article on red-flag identifier which is

clear and precise

given me confidence after reading and what to be aware of.

thank you