Shutterstock.com / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Around 237 million medication errors occur in England per year and nearly 28% of these have the potential to cause harm[1]

. Since the publication of ‘An organisation with a memory’[2]

and ‘Building a safer NHS for patients’[3]

, much progress has been made with regards to the detection, reporting and learning from patient safety incidents. However, the 2014 Patient Safety Alert ‘Improving medication error incident reporting and learning’[4]

described poor data quality for medication incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning Service (NRLS), with 49% of incident reports missing records of actions taken to prevent recurrence and 69% of reports missing details of any apparent causes of the incident[5]

.

This article outlines the steps to be taken immediately following identification of a medicines safety incident. Details of the investigation, reporting and shared learnings are included, along with information about how to support the healthcare professionals involved.

Why all incidents must be investigated

In its ‘Professional standards for the reporting, learning, sharing, taking action and review of incidents’, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society recommends that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians investigate and learn from all incidents, including those that cause harm and those that cause “no harm” or are deemed a “near miss”[6]

.

Investigating patient safety incidents enables healthcare professionals to understand what led to the incident or near miss, and provides an opportunity to introduce changes in practice and reduce the likelihood of recurrence. The investigation also facilitates learning — locally for the team involved, and more widely through national reporting and learning systems[7]

.

The process

Patient safety is reliant on a culture that is open and honest and is supported by reporting, sharing, learning and taking action on patient safety incidents and reviews. The following sections outline the processes that pharmacists and other healthcare professionals should undertake in this situation.

Immediately or shortly after a patient safety incident is identified

Establish whether the patient has received any medicine as a result of this incident

If the patient has received medicine, they will require assessment as immediate clinical action may be necessary (e.g. administration of naloxone if an incorrectly high dose of an opiate has been administered). Administration of other unintended medicines or doses may not have such immediate effects; however, patients may still require a clinical examination or additional monitoring for a period of time.

Pharmacists can advise patients and other healthcare professionals on the effects of unintentional medicine, as well as any other medication the patient may be taking and any related medical conditions.

Patients may need to make an appointment with their GP or specialist consultant

This may be appropriate for patients who were dispensed an incorrect medicine some time previously and have taken it for several days or months.

Pharmacists working in primary care should consider contacting the patient’s GP or specialist consultant to provide relevant information, including:

- The medication that was dispensed;

- The amount of medication the patient has taken, and for how long.

In secondary care, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should ensure that the patient’s named nurse, ward manager and medical team are communicated with, in order to make them aware that the patient received an unintended dose (or doses) of medication.

Where a patient is unaware that they have experienced a medicine incident, pharmacy professionals must be open and honest about what has happened

All pharmacy professionals, as well as other healthcare professionals, have a professional duty of candour to notify patients when something goes wrong with their treatment or care, and causes, or has the potential to cause, harm or distress[8]

.

The patient safety incident or near miss should be reported and the healthcare professionals involved should be informed as soon as possible

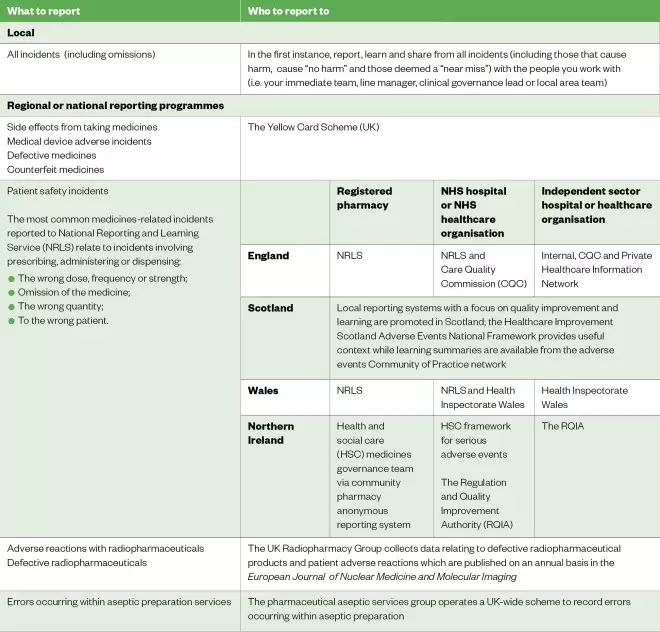

Different types of incidents are reported to different reporting programmes. Guidance on what to report and who to report it to is provided in Table.

Table: What to report and who to report to

Reproduced with permission from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society[6]

All relevant healthcare professionals should be alerted to the occurrence of any incident that occurs and notified that they may be called on during the generation of an incident report.

Investigating the incident

This is based on root cause analysis — a method of problem solving used to identify the cause of faults or problems that is promoted by the National Patient Safety Agency[9]

. Although the effectiveness of root cause analysis in healthcare is a topic of debate[10],[11]

, the basic process is relatively standardised[12]

:

- Identify the incident and decide to investigate;

- Select people for the investigation team;

- Organise and gather data;

- Determine the incident chronology;

- Identify the care delivery problems;

- Identify any contributory factors;

- Make recommendations and develop an action plan.

An investigation should be started as soon as possible after the patient safety incident is identified. In the case of serious incidents (e.g. when a patient has come to harm), a formal process will need to be followed. Information supporting this process can be found in the NHS Improvement serious incident framework[13]

. It may be necessary to select appropriate experts for investigation of serious incidents. Ideally, an investigation team should consist of three or four people facilitated by the investigation leader.

Collect data related to the incident, including facts, knowledge and physical items

To determine the chronology and identify the care delivery problems and contributory factors, data should be gathered as thoroughly as possible. Records, documentation, forms and physical items related to the incident should be collected (e.g. the prescription or incorrectly dispensed item). If a patient safety incident occurred in the past, guideline and procedure implementation dates should be confirmed because it may be necessary to retrieve the version that was in use at the time of the incident.

Request that all healthcare professionals involved in the incident make a record of their actions

This should not wait until the start of a formal process. Support should also be offered to healthcare professionals throughout the investigation process (see Box 1).

Interviews with healthcare professionals and other people involved in the incident are a valuable source of information. The information sources used and knowledge sought during an event could highlight gaps in training and additional learning needs. For more complex incidents, consider having two interviewers present to assist with recording details of the interview. Useful guidance on conducting interviews is provided by Taylor-Adams & Vincent in their ‘London Protocol’[12]

.

Where possible, visit the location of the incident with the healthcare professionals involved

Investigators should ask themselves why the actions made sense to the person who was there at the time[14]

. Although the investigators may be familiar with the environment (e.g. when investigating an incident that occurred in their own dispensary), walking through the incident can aid recall and identification of contributory factors, including colocation of similar products, poor layout of physical environment, distractions and physical demands[15]

.

In 2012, Lawton et al. undertook a systematic review of 83 research studies focusing on the causes of hospital patient safety incidents, which resulted in an evidence-based framework of accident causation in hospitals[16],[17]

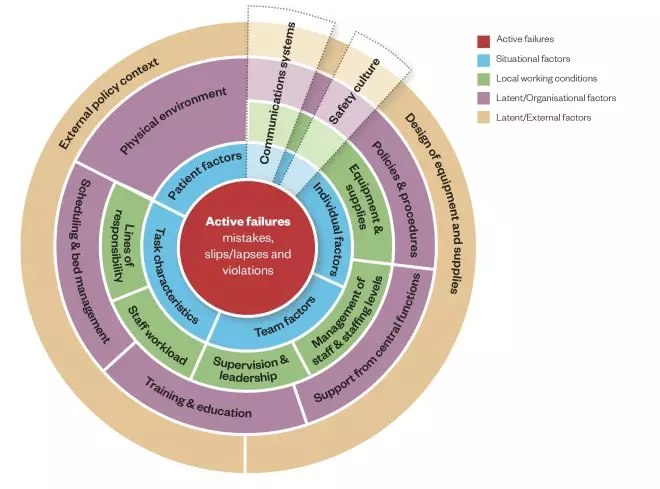

. The Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework is a useful tool to help identify contributory factors (see Figure)[16]

. In the centre of the framework are active failures, around which are a series of circles representing situational factors, local working conditions and two layers of latent factors (those relating to the organisation itself and those relating to wider external policies).

Figure: The Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework

Source: BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:369–380

This model is based on a framework of factors contributing to patient safety incidents in hospital settings. Active failures are included in the centre of the framework, around which are a series of circles representing situational factors, local working conditions and two layers of latent factors: those relating to the organisation itself and those relating to wider external policies.

Using Lawton et al.’s research, a team of practising clinicians and human factors experts created a two-page checklist that is free to access and can be used when asking questions during investigation interviews[17]

.

Following data gathering and completion of interviews, it is important to establish a chronology of the patient safety incident

Developing a timeline leading up to and immediately following a patient safety incident will highlight information gaps, care delivery problems, contributory factors and areas of good practice[9],[12]

. It is important at this stage not to make assumptions and to explore unanswered questions, which may require further interviews with people involved in the incident.

Use the information gathered to make recommendations and develop an action plan

Listing the care delivery problems and contributory factors — and assigning at least one action to each — can help to build an action plan.

Recommending complex, resource-intensive actions — or actions outside the remit of investigators, or the remit of their organisation (e.g. ‘implement an electronic prescribing and administration system across the organisation with immediate effect’ or ‘change the packaging to prevent future selection errors’) — should be avoided where possible.

Actions should be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely) and responsibility for each one should be allocated to appropriate individuals, along with a time frame for implementation. It would be useful to appoint an individual to monitor progress against the action plan to reduce the likelihood of non-completion. It may also be useful to involve frontline staff in any agreement on actions and timescales.

Communicate the action plan to all named individuals to confirm their agreement

This may be vital for success in implementing the action plan, especially in large organisations.

Review the actions set out in the action plan

Delivery of actions should be measured (e.g. through audit, key performance indicators or observational assessment). Organisations should have a process for ensuring action plans are completed, such as through a governance or safety committee, or via an action log. If actions have not been completed, the reasons for this should be explored and every effort should be made to implement the necessary changes.

Sometimes it may be necessary to adapt an action plan. A record of the decision to do so should be made and deadlines should be amended accordingly.

Box 1: Supporting healthcare professionals involved in a patient safety incident

Throughout the incident investigation process, the outcome and concern for the patient will take priority. However, the healthcare professionals involved in medicine incidents often experience emotional distress following the event[18]

.

Investigators and managers should recognise the potential impact that being involved in a medicine incident may have; therefore, they should ask the healthcare professional questions such as ‘How do you feel?’. Venus et al. measured the professional and personal impact of medical errors on French GP trainees: 64% of participants said they were at least strongly affected by their error and the most frequently reported feeling was guilt[19]

.

Whether to withdraw a member of the team from practice is not always a straightforward decision and each situation will have different variables. Managers will need to take into account current staffing levels, as removing one individual or role from a team may put additional pressure on others. Managers will also need to ensure that the individual retains, or regains, their competence and confidence.

The ‘Just culture guide’ published by NHS Improvement can be used to help support conversations between managers about whether a healthcare professional involved in a patient safety incident requires specific individual support or intervention to work safely[20]

. The questions aim to clarify whether an individual needs support or management versus whether the factors and issues involved have a wider scope. The questions also help reduce unconscious bias and ensure consistent, constructive and fair treatment. Scenarios to support training people in using the guide are also available[21]

.

If it is appropriate for the individual to withdraw from practice for a period of time, it is good practice to confirm the purpose for withdrawal, set a review date and agree the action to be taken during this time.

In the longer-term, managers should follow up the incident and find out how the healthcare professional is feeling. Asking questions, such as ‘What troubles you now?’, may help.

Sharing what has been learnt

Following identification, reporting and investigation of a patient safety incident, it is good practice to share local learning more widely[6]

, potentially through the organisation’s medication safety group (or equivalent), the local pharmaceutical committee or the medication safety officer (MSO) network (see Box 2).

The MSO network provides an environment for sharing learning from local patient safety incidents, and for highlighting locally identified risks nationally. Alongside the national network, MSOs in primary and secondary care also network at a regional level, and the Community Pharmacy Patient Safety Group comprises MSOs working in community pharmacy[22]

.

Box 2: Medication safety officers

The medication safety officer (MSO) role was established in England in 2014[4]

in order to improve reporting of and learning from medication error incidents.

All NHS trusts, large independent sector companies, large home healthcare companies and community pharmacy companies with more than 50 community pharmacies registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council are required to have a named MSO registered with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

The National Pharmacy Association has a named MSO for all independent community pharmacy contractors with fewer than 50 branches. Although not mandatory, many clinical commissioning groups have a named MSO.

Further information about the role of MSOs can be found here.

Pharmacists and pharmacy professionals should understand the circumstances that led to a patient safety incident or a near miss. Knowing how to undertake effective and thorough investigations is essential to optimise learning and take appropriate actions to prevent incidents from occurring in the future.

References

[1] Elliott R, Camacho E, Campbell F et al. Prevalence and economic burden of medication errors in the NHS in England. Policy Research Unit in Economic Evaluation of Health and Care Interventions. Universities of Sheffield and York. 2018. Available at: http://www.eepru.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/eepru-report-medication-error-feb-2018.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[2] Department of Health. An organisation with a memory: Report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS. 2000. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105144251/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4065086.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[3] Department of Health. Building a safer NHS for patients: Implementing an organisation with a memory. 2007. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/DH_4097460 (accessed February 2019)

[4] NHS England and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Patient Safety Alert; Stage 3 Directive. Improving medication error incident reporting and learning. 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/psa-med-error.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[5] NHS England and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Patient Safety Alert; Supporting information. Improving medication error incident reporting and learning. 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/psa-sup-info-med-error.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[6] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professional standards for the reporting, learning, sharing, taking action and review of incidents. 2016. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Professional%20standards/Error%20Reporting/rslar-standards-nov-2016.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[7] NHS Improvement. Learning from patient safety incidents. 2018. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/learning-from-patient-safety-incidents/ (accessed February 2019)

[8] Joint statement from the Chief Executives of statutory regulators of healthcare professionals. Openness and honesty: the professional duty of candour. 2015. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/joint_statement_on_the_professional_duty_of_candour.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[9] National Patient Safety Agency. Seven steps to patient safety. 2004. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150505145833/http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/seven-steps-to-patient-safety/?entryid45=59787 (accessed February 2019)

[10] Peerally MF, Carr S, Waring J & Dixon-Woods M. The problem with root cause analysis. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:417–422. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005511

[11] Trbovich P & Shojania KG. Root-cause analysis: swatting at mosquitoes versus draining the swamp. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:350–353. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006229

[12] Taylor-Adams S & Vincent C. Systems analysis of clinical incidents: the London protocol. 2004. Available at: https://www1.imperial.ac.uk/resources/C85B6574-7E28-4BE6-BE61-E94C3F6243CE/londonprotocol_e.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[13] NHS Improvement. Serious incident framework. 2015. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/serious-incident-framework/ (accessed February 2019)

[14] Reason J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000;320:768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

[15] Patient Safety First. ‘How to’ guide for implementing human factors in healthcare. 2009. Available at: https://chfg.org/how-to-guide-to-human-factors-volume-1/ (accessed February 2019)

[16] Lawton R, McEachan RR, Giles SJ et al. Development of an evidence-based framework of factors contributing to patient safety incidents in hospital settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:369–380. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000443

[17] Improvement Academy. An evidence based framework for investigating safety incidents. Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework. 2014. Available at: https://improvementacademy.org/resources/an-evidence-based-framework-for-investigating-safety-incidents/ (accessed February 2019)

[18] Wu AW & Steckelberg RC. Medical error, incident investigation and the second victim: doing better but feeling worse? BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:267–270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000605

[19] Venus E, Galam E, Aubert Jet al. Medical errors reported by French general practitioners in training: results of a survey and individual interviews. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:279–286. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000359

[20] NHS Improvement. Just culture guide. 2018. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2490/NHS_0690_IC_A5_web_version.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[21] NHS Improvement. Scenarios to support training in using a just culture guide. 2018. Available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2491/Scenarios_to_support_training_in_using_a_just_culture_guide_6nJQ8A9.pdf (accessed February 2019)

[22] Community Pharmacy Patient Safety Group. 2017. Available at: https://pharmacysafety.org/ (accessed February 2019)