In 2022, The Pharmaceutical Journal investigated the promotion of diet pills to a fictional 16-year-old girl on the social media platform TikTok.

Results of the investigation revealed that, as of August 2022, almost one-third (31%) of the 100 most popular TikTok videos appearing under the hashtag ‘#dietpills’ were actively promoting the use of diet pills for weight loss to the account.

In addition, 26% of these posts promoted a specific named prescription-only medication (POM), such as the appetite suppressant phentermine, anti-epileptic topiramate, and the alcohol and opioid addiction treatment naltrexone.

TikTok has a policy that restricts the advertising of weight-loss products, particularly to those aged under 18 years, first published in 2020.

In its community guidelines, most recently updated in August 2025, TikTok says that it does not allow “content that promotes disordered eating, risky weight loss or muscle gain methods, or harmful body comparisons”.

It also states that it removes any content that falls under the “not allowed” rules in its community guidelines.

With this in mind — and the explosion in the use of weight-loss drugs over the past few years (data suggest that up to 2.5 million people in the UK are taking the drugs) — The Pharmaceutical Journal wanted to find out if things have improved since the original investigation.

Taking the same approach as 2022, we set up an account registered as a female, this time born in August 2009, making them 16 years old at the time of the investigation in October 2025.

With a clean search history, we then searched the hashtag ‘#dietpills’ and viewed the 100 most popular videos under the hashtag.

This time, 15% of the top videos were actively promoting the use of diet pills — half of that in 2022.

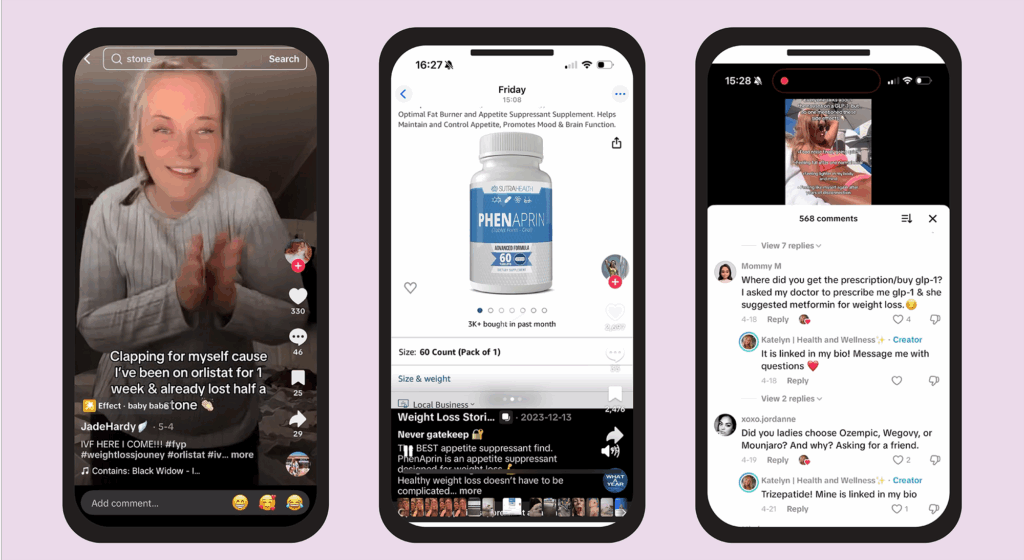

Drugs and products mentioned included over-the-counter (OTC) weight-loss medicine orlistat, which was mentioned five times, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RAs) Mounjaro (tirzepatide; Eli Lilly), which was mentioned four times. Wegovy (semaglutide; Novo Nordisk), tirzepatide, OTC laxative Dulcolax (bisacodyl; Sanofi) and supplement Phenaprin were all mentioned once (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Drugs and products shown in TikTok videos promoting use of weight-loss drugs

The Pharmaceutical Journal

This time, none of the most popular posts mentioned anti-epileptic or addiction treatments, and most videos under the hashtag were discussing people’s experiences of taking the drugs, including their side effects, such as headaches, anxiety and loss of appetite.

Nabil Boulos, specialist pharmacist in paediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Southampton Children’s Hospital, says the data show a “welcome drop” in the quantity of videos promoting weight-loss products.

However, he notes that videos sharing people’s experiences of using the drugs can still be problematic.

The problem is that social media tends to magnify the extremes, focusing on either the most successful weight-loss stories or the most intense side effects

Nabil Boulos, specialist pharmacist in paediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Southampton Children’s Hospital

“The problem is that social media tends to magnify the extremes, focusing on either the most successful weight-loss stories or the most intense side effects or complications of treatment. Without context, these extreme views are problematic and do not represent the weight management journey most young people experience.

“Many young people are already receiving these therapies, and we know they continue to use social media to learn more about their treatments, or to make decisions around them,” Boulos adds.

“Misinformation or skewed views about the benefits or side effects can be damaging to this group for decision-making.”

GLP-1 RAs are not currently licensed in the UK for patients aged under 18 years but they can be prescribed off-licence to children aged 12–17 years who are severely obese with other comorbidities through specialist weight-loss clinics.

As such, it is hard to obtain data on how many children are on weight-loss drugs, but analysis published by NHS England in May 2025 revealed that 4,784 children and young people aged 2–18 years had received care through these clinics.

The rise of retatrutide

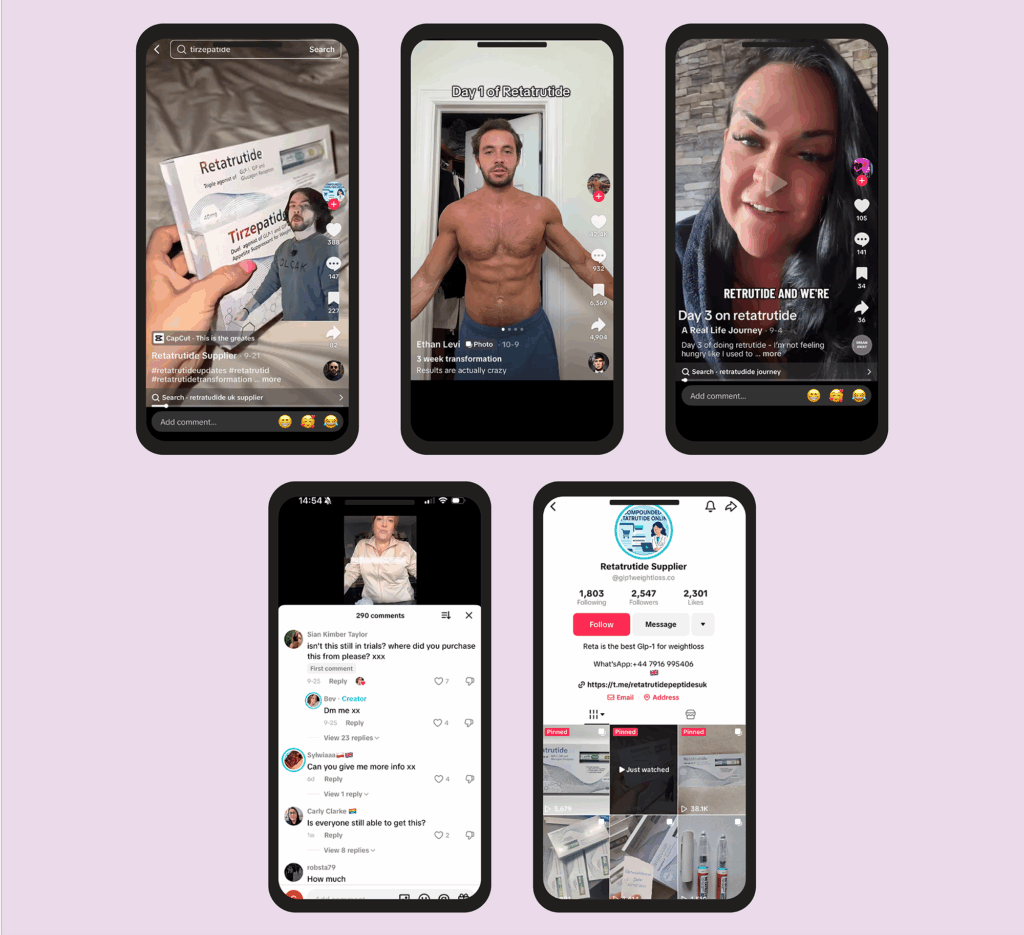

We went on to search each of the drugs/products mentioned and viewed the top ten videos under each one. These videos mainly focused on people’s experiences of taking the drugs, but one video advertising the drug retatrutide appeared under the search for ‘tirzepatide’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Posts showing or referring to retatrutide

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Retatrutide is a once-weekly injection for weight loss under development by Eli Lilly and, at the time of publication, was going through phase III clinical trials. It is not yet approved or available on the market.

It differs from other weight-loss drugs, such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, because it is a first-in-class ‘triple agonist’ that targets three hormones: GLP-1, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon.

When trying to view the creator’s profile as our fictional 16-year-old, it had been restricted, as had the search term ‘retatrutide’. However, when attempting the same search using an adult account, the profile was fully visible and shown to be selling supposed retatrutide pens, but ‘retatrutide’ was still restricted as a search term.

However, misspelling the drug name — for example, ‘retutrutide’ — gave way to hundreds of videos discussing use of the drug.

In September 2025, an investigation published by the BMJ revealed that patients were being pushed towards the black market to purchase weight-loss drugs, which it suggested may be because of poor access to drugs on the NHS and the Mounjaro price hike.

An investigation by Channel 4 News, published in October 2025, uncovered a black market of potentially fake weight-loss jabs being sold on TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube, with the most popular being retatrutide.

In the same month, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) seized more than 2,000 unlicensed tirzepatide and retatrutide weight-loss pens, along with raw chemical ingredients and “tens of thousands” of weight-loss pens ready to be filled, from a warehouse in Northampton.

Links to the wider web

Four of the TikTok videos we viewed under the ‘#dietpills’ hashtag were from accounts that asked viewers to click a link in their ‘bio’ or send a direct message to them to order weight-loss drugs.

When trying to view links in creator’s bios, we were unable to see these as our fictional 16-year-old, but we were able to view all of these on an account registered to an adult, demonstrating that TikTok is moderating content for users aged under 18 years.

However, there was also promotion of external websites to access weight-loss drugs and supplements in screenshots or the comment sections of videos.

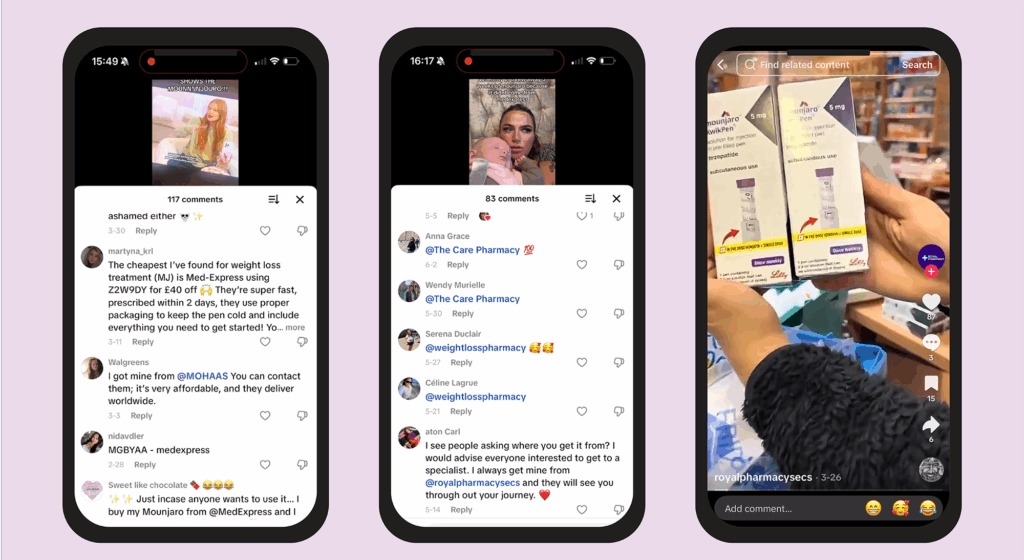

Multiple comment sections on videos included the mention of ‘MedExpress’, along with a discount code for weight-loss drugs, while others tagged supposed online pharmacies (see Figure 3).

These accounts had been blocked when we tried to look at them, aside from @royalpharmacysecs.

Figure 3: Comment sections mentioning MedExpress and pharmacy accounts

The Pharmaceutical Journal

MedExpress is an online pharmacy that has been operating since 2013. Through its website, patients can be prescribed treatments for a range of conditions, including for weight loss.

When questioned about accounts on TikTok promoting its website, as well as a discount code in comment sections, a spokesperson for MedExpress said: “We have a referral scheme that applies to the entire MedExpress service, not to specific products.

“Our terms and conditions clearly state that referral codes must not be shared publicly, including on social media or online forums. Where codes are shared inappropriately, we may take appropriate action, including cancelling credit.

“Weight-loss medication is a serious medical treatment designed to support people who meet strict eligibility requirements set by our medical team. Completing a consultation with MedExpress does not guarantee access to medication.”

We strongly encourage people to seek accurate, reputable medical information rather than relying on personal experiences shared online

Spokesperson for MedExpress

“While conversations about weight-loss medication are increasing on social platforms, we strongly encourage people to seek accurate, reputable medical information rather than relying on personal experiences shared online, as individual circumstances can differ greatly.”

The Pharmaceutical Journal attempted to order weight-loss injections through the MedExpress website as the fictional 16-year-old. The website takes you through a questionnaire when attempting to order the drugs.

This includes asking you to confirm that you are aged 18–74 years. While it is possible to lie at this point in the questionnaire, on the final order summary page, the website states that you must supply details of your GP surgery.

MedExpress, among other online pharmacies, was featured in the MHRA’s advertising investigations for medicinal treatment services for weight loss in September 2025.

MedExpress Enterprises Ltd has amended their advertising to ensure that POMs for weight loss … are not promoted to the public

Spokesperson for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

A spokesperson for the MHRA told The Pharmaceutical Journal: “MedExpress Enterprises Ltd (trading as MedExpress) has amended their advertising to ensure that POMs for weight loss (including reference to GLP-1s, or to ‘weight-loss injections’ or similar) are not promoted to the public. This follows MHRA action on complaints we received.

“Advertising regulations prohibit the publishing of an advertisement to the public that is likely to lead to the use of a POM,” they added.

A spokesperson for MedExpress said: “Following the MHRA’s review, we made clarifications to ensure our advertising aligns with regulatory guidance. We will continue to revisit and monitor our processes, including carrying out internal training to ensure that our content adheres to regulations.

“We remain committed to maintaining compliance with all relevant regulations and ensuring clear, accurate information is shared with patients.”

After viewing a TikTok video of an account advertising ‘Phenaprin’ and showing it to be available on Amazon (see Figure 1), we searched for the product on the UK Amazon website but were unable to find it. The product is, however, available on the US Amazon site.

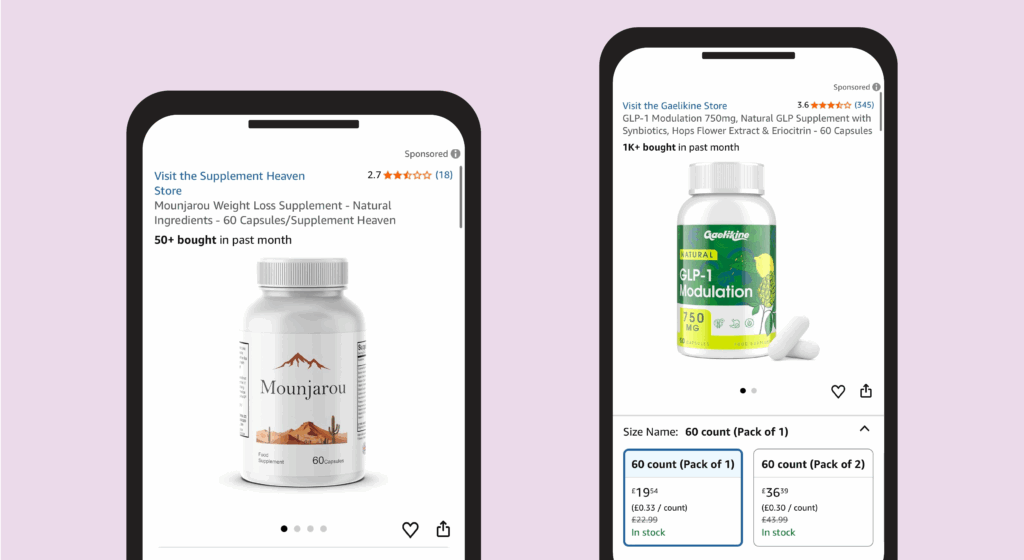

We also discovered products on the UK Amazon site advertised to contain only natural ingredients, but with names containing ‘GLP-1’ or using a similar spelling to ‘Mounjaro’ (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Products being sold on Amazon

The Pharmaceutical Journal

In response to a question on whether Amazon has any processes in place to prevent young people buying what they may deem to be weight-loss drugs, a spokesperson for the online retailer said: “We require all products offered in our store to comply with applicable local laws, regulations and Amazon policies.

“We do not sell Phenaprin, nor do we sell products for purchase by children.

“We also have proactive measures in place to prevent suspicious, non-compliant and prohibited products from being listed, and we continuously monitor our store.”

Social media as a tool for good

It is possible that people, including children and adolescents, can use social media as a tool for genuine, safe advice on the use of weight-loss drugs.

Interspersed among the top videos under the ‘#dietpills’ hashtag were videos featuring a verified healthcare professional discussing eligibility for GLP-1 RAs and how to safely take them, such as TV doctor Sara Kayat on This Morning.

In 2025, Kat Bicknell, a professor of cardiovascular and regenerative medicine at the University of Reading’s School of Pharmacy, conducted a research project with her students looking at discussions of weight-loss drugs on the online forum Mumsnet to see what sort of advice was being given.

She says they began the project assuming the worst. “Before starting the research, we assumed that advice being given without professional guidance on online discussion boards might be unsafe or, if not, misguided.”

However, the research revealed the opposite. “In contrast, we found very little evidence that the well-intentioned advice being given was unsafe, and it was not uncommon for recommendations for people to see a healthcare professional to be made.

Our research did identify reports of side effects by online discussion board users that are not currently associated with these medications or reported in the clinical trials

Kat Bicknell, a professor of cardiovascular and regenerative medicine at the University of Reading’s School of Pharmacy

“Descriptions of rare but serious side effects or unusual side effects often prompted discussion from users to recommend that medical advice should be sought.

“We found that online discussion forums were frequently used to exchange detailed advice that ranged from managing side effects and adjusting dosages to sharing personal motivations and navigating everyday challenges,” Bicknell explains.

However, she notes that occasional posts on obtaining weight-loss prescriptions through online pharmacies reported that supply of the medications had been refused.

“This prompted users who had had similar experiences sharing advice on how to successfully obtain weight-loss medications.

“It was not uncommon for people to ask for information about how to obtain their particular weight-loss medication cheaply, swapping to another online pharmacy or weight-loss service if it was more affordable,” she adds.

“A common theme that we found in our research that we were not expecting was impact that stigma and fear of judgement had on the decisions that people make about their treatment, with many preferring to keep their treatment private, not disclosing their use of weight-loss medications to family, friends or even their GP. This desire for privacy and fear of judgement forced many to rely on online discussion forums for support.

“It was reassuring that the majority of the advice given was not unsafe, but many people are using weight-loss medications without clinical oversight. Our research did identify reports of side effects by online discussion board users that are not currently associated with these medications or reported in the clinical trials.”

Education via social media

In October 2025, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) announced that social media would be employed as a means of educating people on the use of weight-loss drugs in Europe through its plans to partner with online content creators to promote the safe use of GLP-1 medicines as part of its #HealthNotHype campaign.

“The selected creators are mostly healthcare professionals or experts in nutrition. The main channel for this first campaign is Instagram, due to the high volume of conversations and information on GLP-1 receptor agonists circulating on this platform,” the EMA said.

The UK does not currently have a similar campaign, but the Department of Health and Social Care announced in August 2025 that it was partnering with TikTok creators in a campaign to give safe advice to people using social media to plan cosmetic procedures.

Boulos suggests this is something that could be applied to weight-loss medicines. “There is no escaping the access to social media for information in the digital age, nor is it possible to hide all mention of GLP-1 agonists and weight-loss therapies in popular media.

“What is needed is more initiatives by NHS professionals and centres experienced with obesity management to develop reliable online content, designed for and accessible to young people, with an aim to inform and separate fact from fiction.”

The Pharmaceutical Journal shared the accounts promoting weight-loss drugs to our fictional 16-year-old with TikTok.

A spokesperson for the company said it had banned the accounts for violating its community guidelines on the trade of regulated goods and services.

They added that TikTok continues to invest in its trust and safety organisations to strengthen its enforcement strategies.

In its ‘Community guidelines enforcement report’, published on 10 October 2025, data for April–June 2025 showed that 97% of videos that violated its policies on the trade of regulated good and services were removed within 24 hours.

While this is good news, it is evident that videos promoting weight-loss drugs, and in some cases, unapproved drugs, are still managing to reach children and adolescents. With the use of weight-loss products only growing, it is clear that TikTok, along with other social media platforms, will need to do more to protect young people.