LEWIS HOUGHTON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Pharmacy teams struggle each day with the growing challenges that medicine shortages present to the NHS. Various European shortages surveys indicate that medicines shortages are significantly impacting patient care[1–3]. In May 2023, survey results published by The Pharmaceutical Journal revealed 57% of UK pharmacists (1,578) believed medicines shortages had put patients at risk in the past six months[4].

Shortages put strain on pharmacy teams, place economic burden on the healthcare system and compromise patient care, leading to dissatisfaction from both patients and healthcare professionals[5,6]. A roundtable hosted by The Pharmaceutical Journal in April 2023 sought to identify how the impact and management of shortages for pharmacy teams could be improved, highlighting the ongoing need for sustained development efforts in this area[7].

Causes of medicine shortages are diverse and range from supply-related (e.g. manufacturing, regulatory and logistics issues), to demand-related factors (e.g. fluctuating demand, price and reimbursement policies)[8–10]. Emerging trends, such as artificial demand driven by the off-label use of semaglutide for weight loss or for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) caused by the ‘Davina [McCall] effect’, covered in an episode of The PJ Pod in April 2023, can further compound the issue[11–13].

Despite global measures to address shortages and UK government initiatives — including regulations mandating companies to report supply disruptions, the introduction of serious shortage protocols (SSPs), export restrictions and the launch of digital tools, such as the Discontinuations and Shortages Portal (DaSH) — the issue persists[9,14–17].

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams are familiar with the challenges of trying to manage a patient affected by a medicine shortage and behaviours, such as panic-buying and stockpiling, demonstrate the need for a well-informed public.

This article draws on national and global research, professional experience and patient interviews to outline principles on gathering information to inform communications, information sharing and communication with patients, and working and communicating across boundaries to better support affected patients during medicines shortages.

Management of medicines shortages at a national level

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) oversees UK policy, implementing strategic management and mitigation of medicines supply disruptions, collaborating with manufacturers, industry bodies, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), NHS England, regional procurement pharmacy specialists and other stakeholders to prevent shortages and minimise patient risk when they do occur[9,16].

The DHSC medicines supply team (MST) works closely with the NHS England medicines procurement and supply chain (MPSC) team and employs various tools to prevent and manage supply disruptions, often averting potential shortages, including:

- Supporting the expedition of regulatory procedures for products deemed critical;

- Working with companies to manage supply of existing stocks;

- Identifying and liaising with other manufacturers to increase production of the product concerned and/or clinical alternatives;

- Commissioning clinical advice from national experts regarding potential management options;

- Identifying sources of product from abroad, and supporting with expediting import for individual patient use;

- Advising and facilitating communication within the NHS.

This means that while it may look like the UK has many shortages to deal with, there are many more that are managed and prevented that never affect the NHS. Shortages are classified using a tiering system, with the most critical being Tier 4[9]. For shortages designated Tier 2 and above, the DHSC MST may escalate them to the national Medicines Shortages Response Group (MSRG); a multidisciplinary advisory body that provides oversight and support with management and communication planning[9,16]. The group includes clinicians with members across the DHSC, NHS England, Specialist Pharmacy Services (SPS), as well as the devolved administrations and wider NHS.

Communications, drafted by the DHSC MST or NHS England’s medicine procurement and supply chain team, with relevant input from clinical specialists, are aimed at healthcare professionals. These communications, delivered as Medicine Supply Notifications or National Patient Safety Alerts, are accessible on the SPS website[18]. Only in very specific circumstances will patient-facing communications — such as letters to patients, NHS 111 scripts or extracts of information published on the NHS website — be issued.

How to gather information to inform communications

While understanding the broader, growing challenges of medicine shortages is crucial, it is equally important for pharmacy teams to focus on actionable steps they can take to effectively manage and support patients. Practical advice and links to resources available to equip teams in navigating these situations with confidence and efficiency are outlined below.

1. Equip yourself with the correct, consistent information

Before communicating with patients, it is essential to assess the situation to ascertain whether the shortage is genuine, such as a national supply issue, or if it stems from other factors (e.g. a temporary wholesaler delivery delay or misinformation in the media). A step-wise process to gather information should be made (see below).

Access to timely, accurate and concise information on medicines shortages is crucial and was highlighted by pharmacists at The Pharmaceutical Journal‘s roundtable in April 2023, echoing themes that were highlighted at a symposium held at University of Bradford School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences in 2019[7,19].

Information on medicine shortages is issued via controlled dissemination from DHSC and NHS England. This is a closed system and is not accessible to the public. A public-facing information platform containing a full list of shortages does not exist in the UK.

2. Gather further information in a step-wise manner to guide your approach

Current shortages data can be accessed via the SPS Medicines Supply Tool; pharmacy teams should register using an NHS email address[18]. This tool is updated as soon as information changes, so the data are as ‘live’ as possible.

In a study exploring patient preferences regarding communication during medicine shortages, healthcare professionals emphasised the importance of a single version of truth; therefore, it is crucial for all healthcare professionals to refer to the same information source[20].

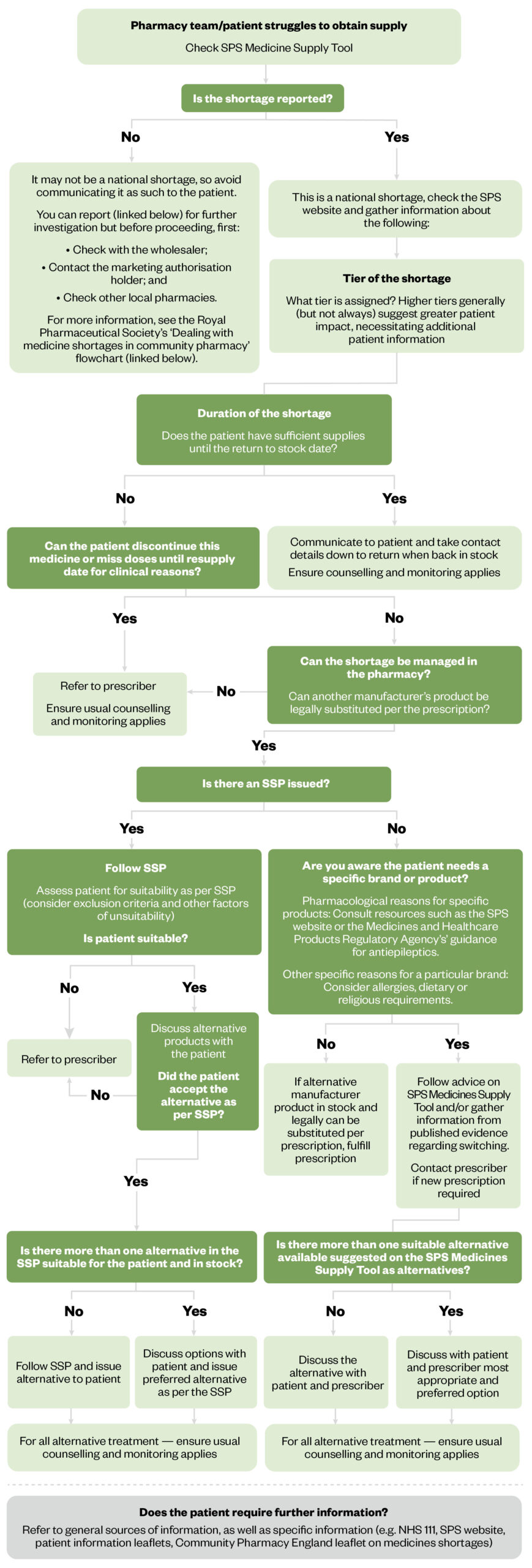

The flowchart in Figure 1 can be used to gather further information to inform next steps and can be used alongside the guidance outlined in the ‘RPS Pharmacy guide: Medicine shortages in community pharmacy‘[21].

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Report a medicine shortage here, and view the Royal Pharmaceutical Society guide here

3. Be aware of resources you can direct patients to

Given the pressurised environment that many pharmacy teams are working in, there may only be a short amount of time to explain the shortage to patients and it is important to understand what patient resources are available and how these can support conversations. Examples include:

- The Medicines Factsheet: Created by Community Pharmacy England[22];

- Patient advocacy groups: DHSC and NHS England work closely with these groups to tailor important messaging to patients for the more critical supply issues. Patient advocacy groups are particularly inclusive as they will have several routes adapted to support their specific population. These include but are not limited to support groups, telephone helplines, online forums and easy-to-read webpages. For example, Diabetes UK has developed an FAQ document to cover everything a patient needs to know about the GLP-1 RA shortages[23];

- National letters and leaflets: During the EpiPen shortage in 2018, several resources were issued[24].

A medicine shortage will often lead to an alternative product being prescribed or dispensed. This may involve utilising SSPs in the pharmacy or consulting the prescriber for an alternative prescription. Standard patient counselling guidance applies in these situations (see ‘RPS Pharmacy Guide: Counselling people on the use of medicines’)[25]. Depending on the medication change; patients may need a change of dose, directions or may just need to know that their medication may look different. SSPs typically include specific patient information and additional guidance may be available on the SPS Medicine Supply Tool. In addition to counselling and a patient information leaflet, patients can be directed to the ‘Medicines A-Z‘ on the NHS website for further information about the alternative medicine prescribed[26].

Principles to support information sharing and communication with patients

Understanding patient expectations is crucial to tailor communication strategies. Patients expect personalised, timely and trustworthy information, with the option to receive it digitally[20].

Choosing a communications method to share this information should not promote digital exclusion — not all patients have access to digital devices or have the capacity to engage with digital resources. Suboptimal communication threatens patient empowerment, satisfaction and may lead to patients taking counterproductive actions. Professional judgement should be used to identify the right communication strategy for each patient, ensuring they receive valuable, reassuring information during consultations.

Try to understand what your patient wants and needs and provide the right sort of information

Striking a balance between providing sufficient information and avoiding overwhelming the patient is crucial yet challenging. Healthcare professionals generally understand the types of information patients want, but there can be a gap in their perception of the appropriate level of detail[20]. There is a diverse range of health literacy levels among patients, so it is important that the information presented and explanation of the information is tailored accordingly.

Important considerations include:

- That the information supplied to each patient is easy to understand and it tailored to vary in response to their individual needs;

- Listening to your patient to understand their preferences regarding the amount of information they desire. Some patients may only wish to be informed about changes in their medication, while others may expect a detailed explanation or wish to participate in shared-decision making, although this may not always be feasible during shortages;

- Being transparent about the shortage and providing accurate information to patients;

- Clearly communicating the reasons behind the shortage but be mindful not to worry patients;

- Demonstrating empathy and understanding towards patients’ concerns and frustrations;

- Active listening will enable you to grasp the individual impact of the shortage on each patient’s wellbeing;

- Contextualising the information you give to patients. For instance, if the medicine is expected to be back in stock before the patient exhausts their current supply, it may not be necessary to discuss alternative options yet. If an alternative is required, maintain a high-level explanation, focusing on why it is necessary and what steps need to be taken. Agree a way forward and encourage patients to reach out for updates or if they encounter any difficulties;

- Educating patients about the prescribed alternatives available during the shortage including information on dosage and side effects. Explain why these alternatives are considered appropriate and provide or direct patients to relevant educational materials from trusted sources to learn more about any alternatives.

Make sure to present the facts that have been shared on the SPS Medicine Supply Tool or if there is no new information available, then be clear that this is the case.

Interactions should be documented where possible (e.g. alternative options discussed and any follow-ups required) within your patient record system. This serves as a valuable reference for future interactions and ensures continuity of care.

If you are a community pharmacist, you should discuss the following with the patient:

- If they currently take the medicine, how many days supply they have and if this is for short- or long-term use;

- If they want to wait for their medicine to come in and wish to be contacted with an update by a certain date;

- If they would like you to contact the prescriber around whether there would be a suitable alternative;

- Whether they would like to try another pharmacy themselves[21].

Typically, patients who seek more information will ask more questions.

Box 1: Useful communication skills articles from The Pharmaceutical Journal

- ‘How to approach challenging scenarios in primary care pharmacy‘;

- ‘Approaching difficult situations: how to have challenging conversations‘;

- ‘How to use clinical reasoning in pharmacy‘;

- ‘How to provide patients with the right information to make informed decisions‘;

- ‘How pharmacists can encourage patient adherence to medicines‘.

Seek to build trust and maintain relationships

Building and maintaining trust is a significant aspect of any communication. Patients trust healthcare professionals to direct them to and share honest information. It is important you trust the source of the information you are sharing with them so they can trust the message communicated.

Set realistic expectations by outlining the expected duration of the shortage and any anticipated changes to the availability of the patient’s medication. You should also discuss potential delays in obtaining specific medicines and propose viable solutions. Where switching is necessary, information will be included in communication issued on the SPS Medicine Supply Tool and you should check for published evidence regarding switching[27]. Patients who have been on a specific medicine for a long time may feel anxious about switching. Engage positively with these patients by building rapport and seek to understand their concerns and preferences. Explain the benefits of the alternative medication in supporting their clinical condition and share information leaflets — see example for imatinib preparations[27].

In some cases, as agreed with the prescriber, the patient may be able to safely discontinue the medication if it is no longer necessary for clinical reasons. If applicable, communicate this option with the patient.

Patients value honesty in communication, regardless of the message’s nature. In contrast, healthcare professionals can be more reserved in their approach; fearing excessive information could inadvertently prompt undesirable patient behaviours, such as hoarding supplies in anticipation of future shortages, non-concordance to preserve their limited supplies, or diminished confidence in their medications, particularly in cases where shortages result from recalls or quality issues[20]. Pharmacy teams should be encouraged to address these behaviours frankly, as this can foster better communication and improved outcomes. Acknowledge that hoarding medications is a natural response for many patients during times of uncertainty but emphasise that it is important to seek professional advice before taking such actions. Discussing the risks associated with rationing medications and highlighting the potential consequences can also empower patients to make informed decisions. By openly discussing these behaviours and providing guidance on appropriate actions, pharmacists can build trust, mitigate potential risks and ensure that patients receive adequate support and care.

Reassure the patient that their wellbeing is your priority and that the team can support them throughout the transition. Offer empathy, encouragement and practical advice to help alleviate their worries, while empowering them to make informed decisions about their health. In some circumstances, you may find the five-step approach to structuring challenging conversations, known as the ‘5 A’s’ useful; see ‘Approaching difficult situations: how to have challenging conversations’[28].

Remember that reporting of medicines unavailability and delays regarding re-supply does not automatically undermine confidence in you as the communicator or the source.

Provide effective patient information services

Several excellent examples of healthcare professional-designed and led information services for patients and communities exist, including those for the ongoing ADHD medicines shortages[29,30]. These offer current insight into product shortages, prescribing pattern changes, alternative products and provide supporting notes to help empower patients to act as needed.

Digital communications to patients are very effective at capturing the attention of a mass audience, especially if placed in spots such as GP surgeries or pharmacy sites[31]. Depending on the nature of the medicines shortage, it may be appropriate to use this communication route and encourage patients to consult their healthcare professional if they have any concerns; however, it is essential to prioritise digital literacy among both patients and healthcare professionals to drive successful adoption and outcomes[31].

Principles for working and communicating across boundaries

The positive impact of sharing medication information between clinical settings (for example, hospital to community pharmacies via the Discharge Medicines Service) demonstrates the importance of continued information sharing[32].

Medicine shortages affect healthcare professionals across all sectors, and a unified and supportive message to patients is essential. While it can be frustrating to request alternative prescriptions from GP practices and await responses, it is equally challenging for GPs to receive requests with limited view of stock availability. Many GP practices have established communication protocols for addressing such issues and may seek details on alternative options, perhaps using information shared on the SPS Medicine Supply Tool.

It is important that you have the information required — prescribers will want to know:

- What the problem is;

- How long the shortage is expected to last for;

- What to prescribe as an alternative;

- Which patient groups are most likely to be affected[21].

Unless there is an exceptional reason, it important to only recommend alternatives listed on the SPS Medicine Supply Tool. These are the options confirmed by the national teams to adequately support any increased demand.

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams should seek to establish communication processes with local GP practices to facilitate prompt resolution of issues and reduce further delays when alternatives are prescribed but unavailable[21].

Practical steps include:

- Identifying designated points of contact who are responsible for communicating issues across the organisation;

- Agree preferred communication channels, frequency of communication and associated documentation and record-keeping;

- Developing a protocol for handling urgent medication shortage issues and any necessary escalation procedures;

- Providing training to colleagues involved in managing and communicating medicine shortages;

- Implementing feedback mechanisms to evaluate the effectiveness of the communication processes and identify areas for improvement.

If these processes are not in place locally, consider working together with the practice pharmacist to set one up, or with your local pharmaceutical committee to create a network of providers, utilising national data from the SPS Medicine Supply Tool to ensure consistency and accuracy across the system. For tips and advice on developing skills to support effective MDT working, see ‘How to work effectively as part of a multidisciplinary team’.

Establishing a process for sharing information can also help facilitate shared learning to enhance coordination and provide comprehensive patient support.

Box 2: Royal Pharmaceutical Society launches project to investigate medicines shortages

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) is leading a project to examine the causes of the growing challenge of medicines shortages and help tackle their impact on patients and pharmacy practice.

A new advisory group, convened by RPS and chaired by Bruce Warner, Deputy Chief Pharmaceutical Officer for England, will bring together experts from primary and secondary care, patients, the pharmaceutical industry, suppliers, regulators, government and the NHS.

The group will develop a report to provide expert thought leadership and support for the wider debate on UK policy. It will provide recommendations to address the factors behind medicine shortages and steps to take to reduce their impact on patient care.

For more information, see: https://www.rpharms.com/medicinesshortages#advisorygroup

- 1Press release: PGEU Medicine Shortages Survey 2019 results. Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union . 2020. https://www.pgeu.eu/publications/press-release-pgeu-medicine-shortages-survey-2019-results (accessed May 2024)

- 2Shortages Survey Report. European Association of Hospital Pharmacists. 2019. https://www.eahp.eu/sites/default/files/shortages_survey_report_final.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 3EAHP Position Paper on Medicines Shortages. European Association of Hospital Pharmacists. 2019. https://www.eahp.eu/sites/default/files/eahp_position_paper_on_medicines_shortages_june_2019.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 4Rise in pharmacists reporting patient safety risks from medicines shortages, shows survey. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.187430

- 5AlRuthia YS, AlKofide H, AlAjmi R, et al. Drug shortages in large hospitals in Riyadh: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2017;37:375–85. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2017.375

- 6McLaughlin M, Kotis D, Thomson K, et al. Effects on Patient Care Caused by Drug Shortages: A Survey. JMCP. 2013;19:783–8. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.783

- 7Designing a more resilient system for medicines supply in the UK. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.184772

- 8Special report: the UK’s medicines shortage crisis. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.189330

- 9A Guide to Managing Medicines Supply and Shortages. NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/a-guide-to-managing-medicines-supply-and-shortages-2.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 10Musazzi UM, Di Giorgio D, Minghetti P. New regulatory strategies to manage medicines shortages in Europe. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2020;579:119171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119171

- 11GLP-1 receptor agonist shortage expected to continue for all of 2024. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2024.1.206500

- 12Breen L, Silcock J, Edwards Z. Ozempic shortages in the UK may last until 2024 – here’s why. The Conversation. 2023. https://theconversation.com/ozempic-shortages-in-the-uk-may-last-until-2024-heres-why-208819 (accessed May 2024)

- 13Coping with the ‘Davina effect’ on HRT. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.182128

- 14Q&A: Addressing critical shortages of medicines in the EU. European Commission. 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_23_5191 (accessed May 2024)

- 15EMA takes further steps to address critical shortages of medicines in EU. European Medicines Agency. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-takes-further-steps-address-critical-shortages-medicines-eu (accessed May 2024)

- 16Reporting requirements for medicine shortages and discontinuations. Department of Health and Social Care. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reporting-requirements-for-medicine-shortages-and-discontinuations (accessed May 2024)

- 17Critical Imports and Supply Chains Strategy. UK government. 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65a6a1c1867cd800135ae971/critical-imports-and-supply-chains-strategy.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 18Medicines Supply Tool. Specialist Pharmacy Service. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/home/tools/ (accessed May 2024)

- 19Breen L. Medicines Availability in the UK Pharmaceutical Supply Chain. University of Bradford. https://www.bradford.ac.uk/pharmacy-medical-sciences/research-innovation/medicines-availability/ (accessed May 2024)

- 2051st ESCP symposium on clinical pharmacy 31 October–02 November 2023, Aberdeen, Scotland. Int J Clin Pharm. 2024;46:214–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01685-8

- 21Medicine shortages in community pharmacy. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/medicine-shortages-in-community-pharmacy (accessed May 2024)

- 22Medicines Factsheet — Information on medicines supply for patients. Community Pharmacy England. https://cpe.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/PSNC-Medicines-Supply-Information-Leaflet-July-2022.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 23FAQs — GLP-1 RA shortages. Diabetes UK. 2024. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/treating-your-diabetes/tablets-and-medication/incretin-mimetics/shortage-FAQs#:~:text=The%20NHS%20is%20currently%20facing,loss%20which%20is%20outstripping%20supply (accessed May 2024)

- 24Fowler A. SDA 2018-001U Letter. NHS England. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SDA-2018-001U-Letter.pdf (accessed May 2024)

- 25Counselling people on the use of medicines. Royal Pharmaceutical Society . 2016. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/counselling-people-on-the-use-of-medicines (accessed May 2024)

- 26Medicines information. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines (accessed May 2024)

- 27Switching between imatinib preparations. Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2022. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/switching-between-imatinib-preparations/ (accessed May 2024)

- 28Approaching difficult situations: how to have challenging conversations. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2021.1.113408

- 29ADHD Medication Shortage 13th October 2023. NHS Grampian. 2023. https://www.nhsgrampian.org/service-hub/child-and-adolescent-mental-health-services-camhs/news/adhd-medication-shortage-13th-october-2023/ (accessed May 2024)

- 30Shortages of some ADHD medications. Alder Hey Children’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. 2023. https://www.alderhey.nhs.uk/shortages-of-some-adhd-medications/ (accessed May 2024)

- 31Berkhout C, Zgorska-Meynard-Moussa S, Willefert-Bouche A, et al. Audiovisual aids in primary healthcare settings’ waiting rooms. A systematic review. European Journal of General Practice. 2018;24:202–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2018.1491964

- 32Discharge medicines service has prevented almost 22,000 hospital readmissions, government says. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.189430