Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

Summary box

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is the leading risk factor associated with death in the world. It is affected by a wide variety of factors, including increasing age, black African or Carribean ethnicity, being overweight and having a lack of physical activity. Primary hypertension, in which no specific cause is found, affects 95% of patients.

Hypertension is typically asymptomatic and only detected through opportunisitic screening. Symptoms only manifest when blood pressure reaches very high levels (usually >200 mmHg systolic), and can include headaches, dizziness and nosebleeds.

It is usually diagnosed when a patient’s blood pressure is repeatedly found to be 140/90 mmHg or higher in a clinical setting and average readings taken using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or monitoring at home are higher than 135/85 mmHg.

Once hypertension has been diagnosed, further tests should be conducted, including urine testing, blood tests, an eye examination and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).

Hypertension is one of the most prevalent cardiovascular risk factors in the world. According to the World Health Organization, high blood pressure was the leading risk factor associated with death worldwide in 2004, accounting for 7.5 million deaths (12.8% of all deaths). It was the risk factor most commonly associated with death in middle-income countries (17.2% of all deaths), the second most common in high-income countries after tobacco use (16.8% of deaths), and the second most common in low-income countries after children being underweight (7.5% of deaths)[1]

.

In England, 32% of men and 29% of women have, or are being treated for, high blood pressure[2]

. Data from general practice indicate that much of the hypertension present in the population is currently undetected, with only 13.8% of those with the condition identified as hypertensive on GP registers.

| Prevalence of hypertension in the UK [3] | ||

|---|---|---|

Number of patients on hypertension register | Detected prevalence (%) | |

England | 7,698,296 | 13.7% |

Scotland | 689,650 | 14% |

Wales | 507,750 | 15.5% |

Northern Ireland | 501,436 | 13.1% |

Total | 9,397,132 | 13.8% |

| Hypertension by age group in the UK [3] | ||

|---|---|---|

Percentage of population with hypertension | ||

Age range | Men | Women |

16–24 years | 5 | 3 |

25–34 years | 6 | 4 |

35–44 years | 25 | 10 |

45–54 years | 37 | 26 |

55–64 years | 51 | 47 |

65–74 years | 65 | 63 |

>75 years | 79 | 79 |

Hypertension is one of the most important preventable causes of premature morbidity and mortality, and lowering blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in people with established hypertension. Each 2 mmHg rise in systolic blood pressure is associated with a 7% increased risk of death from coronary heart disease and a 10% increased risk of death from stroke[1]

.

Pathophysiology

Blood pressure is expressed in terms of systolic blood pressure (higher reading), which reflects the blood pressure when the heart is contracted (systole), and diastolic blood pressure (lower reading), which reflects the blood pressure during relaxation (diastole). Hypertension can be diagnosed when either systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, or both are raised.

Blood pressure is determined by the cardiac output balanced against systemic vascular resistance. The process of maintaining blood pressure is complex, and involves numerous physiological mechanisms, including arterial baroreceptors, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, atrial natriuretic peptide, endothelins, and mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid steroids. Together, these complex systems manage the degree of vasodilatation or vasoconstriction within the systemic circulation, and the retention or excretion of sodium and water, to maintain an adequate circulating blood volume.

Dysfunction in any of these processes can lead to the development of hypertension. This may be through increased cardiac output, increased systemic vascular resistance, or both.

Blood vessels become less elastic and more rigid as patients age, which reduces vasodilatation and increases systemic vascular resistance, leading to a higher systolic blood pressure (often with a normal diastolic pressure). In contrast, hypertension in younger patients tends to be associated with increased cardiac output, which can be caused by environmental or genetic factors.

Risk factors for developing hypertension include:

- increasing age (50% of the population aged over 60 years have hypertension)

- ethnicity — hypertension is more prevalent in patients of Black African or Caribbean descent

- being overweight or obese

- physical inactivity

- excess salt consumption

- excess alcohol intake

- stress

- other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnoea).

No specific cause of hypertension is found for most (>95%) patients with high blood pressure, and this is often referred to as primary or essential hypertension. Secondary causes are identified in the remaining 5% of cases. The list of possible causes is extensive, and includes:

- medicines (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives, corticosteroids, sympathomimetics)

- renovascular disease

- pheochromocytoma

- primary hyperaldosteronism (e.g. Conn’s syndrome)

- coarctation (narrowing) of the aorta

- Cushing’s syndrome.

Patients with suspected secondary hypertension should be referred to a specialist team.

Clinical features

Hypertension is not a disease in its own right, but if left untreated it is a risk factor for acute events (such as myocardial infarction and stroke) and for the development of organ damage.

Chronically raised blood pressure can lead to several conditions related to pressure overload:

- left ventricular hypertrophy, which is the result of chronic pressure overload in the myocardium, resulting in thickening of the muscle; this slows ventricular relaxation and delays filling during diastole, reducing the efficiency of the heart as a pump.

- exacerbation of the development of coronary heart disease, which results in myocardial ischaemia or infarction

- heart failure, as the ability of the heart to meet the demands of the body falls

- thromboembolic or haemorrhagic strokes or transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs)

- chronic kidney disease with proteinuria or albuminuria, as renal perfusion is affected

- retinopathy and haemorrhages of the fundus (the inner surface of the eye).

Hypertension is asymptomatic in most cases, only being detected through opportunistic screening. Symptoms only manifest when the blood pressure reaches very high levels (usually >200 mmHg systolic), and can include headaches, dizziness and nosebleeds. Many patients tolerate high blood pressures (even in excess of 180 mmHg systolic) for significant periods without symptoms or any adverse effects, although these patients are at significant risk of experiencing an acute event or damage to organs including the brain, eyes, heart and kidneys.

Malignant, sometime referred to as accelerated, hypertension is very high blood pressure that occurs suddenly without warning, and can involve systolic blood pressures in excess of 200 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure above 130 mmHg. Malignant hypertension is a medical emergency and requires urgent treatment to limit the acute damage to the brain, eyes, blood vessels, heart and kidneys.

Key signs of accelerated hypertension include blood pressure of >180/110 mmHg associated with signs of papilloedema, retinal haemorrhage, or suspected phaeochromocytoma (which include labile or postural hypotension, headache, palpitations, pallor and diaphoresis). Patients with suspected accelerated hypertension should be referred urgently for review by a specialist on the same day.

Diagnosis

Traditionally, hypertension has been identified by checking a patient’s blood pressure in a clinic repeatedly over a period of 2–3 months. Hypertension was confirmed if the systolic blood pressure was persistently greater than 140 mmHg, or the diastolic blood pressure was persistently greater than 90 mmHg.

This method of diagnosis has significant limitations because the blood pressure measured in the clinic setting may not reflect the blood pressure in day-to-day life. In particular, there are concerns that blood pressure may be artificially raised in the clinic setting in some patients, often referred to as ‘white coat hypertension’, which could result in people receiving unnecessary drug treatment[4]

.

However, in August 2011 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance that brought significant changes to diagnosis in England[5]

. This included the recommendation that hypertension should be diagnosed using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM)[5]

. One of these methods should be used to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension following the recording of a high blood pressure reading in the clinic setting.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is a non-invasive method of obtaining blood pressure readings over a 24-hour period while the patient goes about their normal activities of daily life. Blood pressure measurements are taken every half hour during the day and every hour at night. A patient is diagnosed with hypertension if the average of the daytime blood pressure readings is greater than 135/85 mmHg. Although the night-time pressures are not used, they provide additional information, including whether the patient is a ‘night-time dipper’ (the blood pressure goes down overnight while asleep); if this does not occur, the patient is at a higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

The success of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is reliant on the machine being correctly fitted, and a proportion of readings can fail (for example, if the tubing becomes kinked at the time of cuff inflation). It is therefore important to ensure that the daytime average blood pressure used to diagnose hypertension is based at least 14 successful daytime blood pressure readings. ABPM is the method of choice for diagnosing hypertension in the NICE guidance, as it is the most cost-effective strategy when compared with clinic or HPBM, and there is substantial evidence that it is better than blood pressure measurements in the clinic for predicting future cardiovascular events and target organ damage[4]

.

Home blood pressure monitoring involves the patient taking blood pressure readings in the morning and evening for 7 days at home and recording the results. Each reading involves two consecutive measurements taken at least one minute apart while the patient is seated.

The first day’s results are discarded, and an average of the results of all other readings is calculated. A patient is diagnosed with hypertension if this average is at least 135/85 mmHg[5]

.

It is essential that the patient is supplied with a validated and calibrated blood pressure machine to ensure the accuracy of the readings taken. A list of validated blood pressure machines can be found on the British Hypertension Society website (http://www.bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors).

Staging

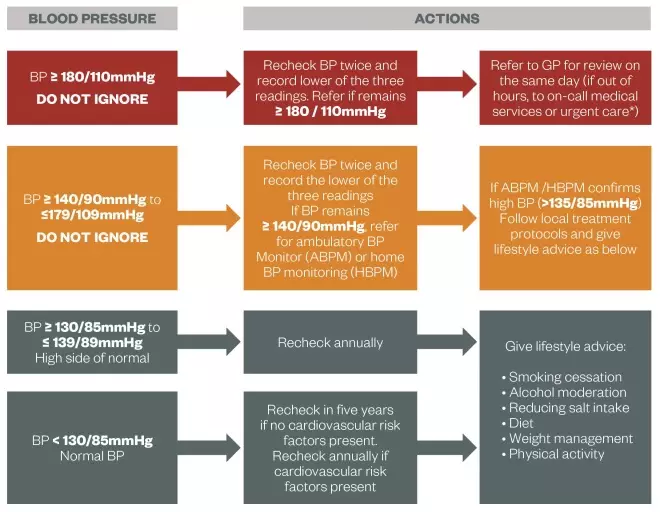

Staging is used to guide management options and the urgency with which the raised blood pressure should be addressed. For example, in severe hypertension, the diagnosis should be made using blood pressure readings from the clinic, and treatment should be started without delay (see ‘Traffic-light guide to blood pressure management’).

Traffic-light guide to blood pressure (BP) management

How to assess patients and the actions you would need to take.

Source: South East London Area Prescribing Committee and South West London Medicines Commissioning Group

*Especially if accelerated hypertension (blood pressure usually higher than 180/110 mmHg with signs of papilloedema and/or retinal haemorrhage) or suspected phaeochromocytoma (labile or postural hypotension, headache, palpitations, pallor and diaphoresis).

High-risk patients

Once diagnosed, all patients with hypertension should have a series of further tests and investigations:

- urine testing for the presence of protein by checking the albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) and testing for haematuria using a reagent strip

- blood tests to measure plasma glucose, electrolytes, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

- eye examination to check for hypertensive retinopathy

- a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) to check for signs of left ventricular hypertrophy or ischaemia.

People younger than 40 years of age with hypertension should also be considered for specialist referral to establish if there is any underlying causes of hypertension and to identify any early target organ damage.

A full cardiovascular risk assessment should be undertaken for all patients (except in the presence of pre-existing cardiovascular disease; in England and Wales, NICE recommends the using the QRisk2 calculator (www.qrisk.org), although others are available. This takes into account the patient’s age, gender, ethnicity, blood pressure and total cholesterol:HDL ratio as a minimum to calculate the percentage risk of developing cardiovascular disease over the next 10 years. Patients with a cardiovascular-disease risk of ≥ 20% require more intensive treatment for their hypertension.

Other patients with a higher risk of future cardiovascular events also require more intensive treatment (see ‘Hypertension: management’). This includes patients with established cardiovascular disease (prior coronary heart disease, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, or peripheral arterial disease), diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

Helen Williams is a consultant pharmacist for cardiovascular disease at Southwark Clinical Commissioning Group.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva: WHO 2009.

[2] Joint Health Surveys Unit. Health Survey for England 2010. Leeds: The Information Centre, 2011.

[3] British Heart Foundation. Coronary Heart Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation, 2012

[4] Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P et al. Cost-effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study. Lancet 2011, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61184-7.

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension: Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults. London: NICE, 2011.