Tabletalkmedia

Cancer learning ‘hub’

Pharmacists are playing an increasingly important role in supporting patients with cancer, working within multidisciplinary teams and improving outcomes. However, in a rapidly evolving field with numbers of new cancer medicines is increasing and the potential for adverse effects, it is now more important than ever for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of the principles of cancer biology, its diagnosis and approaches to treatment and prevention. This new collection of cancer content, brought to you in partnership with BeOne Medicines, provides access to educational resources that support professional development for improved patientRaising awareness

Pharmacy teams can raise public awareness of cancers and their causes, and play a part in improving prevention and early detection of cancers[7] . The practicalities of training pharmacy teams to provide this and examples of five such schemes are described in the ‘Accelerate, coordinate and evaluate’ programme report[8] . Several national initiatives can be used as a basis to help pharmacy teams engage with and inspire their patients to initiate conversations (see Box 1)[9],[10] ,[11] . The WWHAM pharmacy patient questioning process is a good starting point because it can provide relevant answers[12],[13] :- Who is the medicine for?

- What are the symptoms?

- How long has the patient had the symptoms?

- What action has been taken already?

- Are they taking any other medication?

Box 1: Initiatives to help pharmacy teams to engage with patients

- ‘Making every contact count’ by Public Health England[9]

- ‘The whites of your eyes’ by the National Pharmacy Association [10]

- Healthy Living Pharmacies[11]

Red flag identification

Red flags can be described as an alarm or warning signs and symptoms that suggest a potentially serious underlying disease, such as cancer[3] . A practical guide to red flag symptoms necessitating referral can be found in Table 1[16] and non-specific symptoms in Box 2. Several factors should be considered when examining the clinical features that help to identify a symptom as a red flag. These include:- Duration — when do harmless symptoms become red flags?

- Demographics — age is an important determinant of cancer risk.

- Clinical features — anything presenting as ‘not normal’ for the patient should be considered.

| Table 1: Red flag symptoms necessitating referral | |

| Source: suspected cancer guidelines based on the Quick Reference Guide for Pharmacists 2017[16] | |

| Lung | Age 40 years and over with:

|

| Oral [14] |

|

| Upper gastrointestinal |

|

| Lower gastrointestinal |

|

| Skin moles | Any age:

|

| Renal tract | Age 45 years and over with:

|

| Head and neck |

|

| Breast |

|

Box 2: Non-specific symptoms

- Unexplained bleeding (rectal, vaginal, bruising);

- An unusual lump or swelling anywhere on the body;

- A sore that does not heal — skin or surface symptoms;

- Unexplained weight loss;

- Very heavy night sweats;

- An unexplained pain or ache;

- Appetite loss;

- Fatigue;

- Pruritis.

When to refer

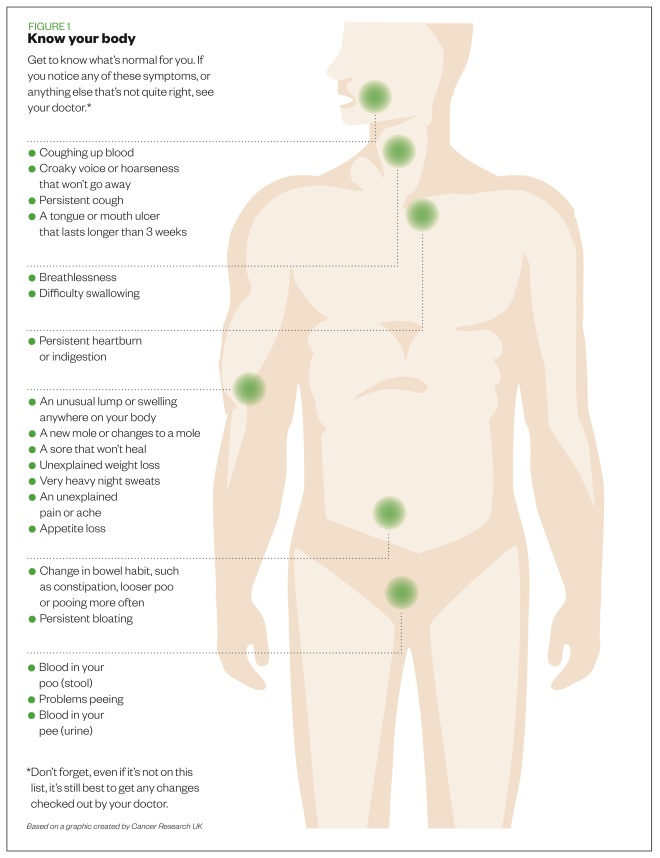

A useful tool to have in the pharmacy for patients is the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) guide ‘Spotting cancer early saves lives’, which has a section on ‘Know your body’ (see Figure 1)[18] . Pharmacy teams must also be aware of and educate patients to recognise the general red flag symptoms shown in Table 1, some of which include unexplained weight loss and excessive tiredness.

Figure 1: Early warning signs of cancer

Source: Cancer Research UK

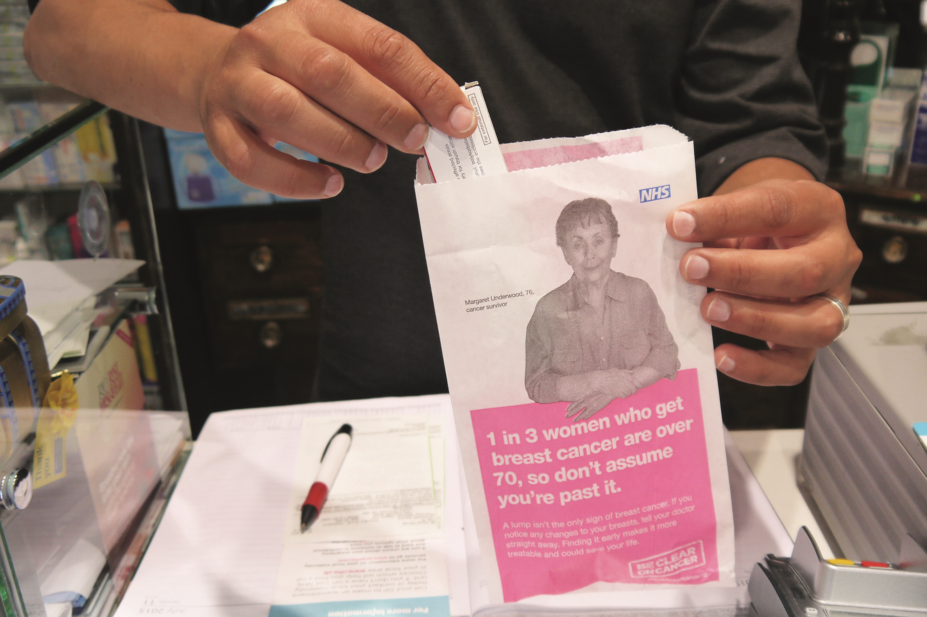

Ensuring referral happens

It is important to minimise patient fears but provide support to achieve referral. Support can be offered by addressing appointment barriers, asking patients to let you know how they got on, and helping them to have a meaningful conversation with their GP by writing down worrying symptoms and what may aggravate or relieve those symptoms. Analysis of the ‘Be clear on cancer’ campaigns showed that public awareness of symptoms and reporting appears to be increasing[20] . It is important to overcome potential rejection of referral advice leading to lack of attendance by patients at any stage in the diagnostic process. A different approach may be needed to change public perception of GP approachability (see Box 3). Work has been carried out to assess and quantify these barriers[21] . Pharmacy professionals should reinforce the message by ensuring the patient does not delay going to see their GP about their ‘worrying symptoms’. Conversational tips to engage the patients and attempt to overcome barriers are outlined in Box 4. Talking through these barriers is helped with using the questioning processes previously described (e.g. WWHAM). Awareness of the behaviour change cycle and patient beliefs about their health is important to any discussion. For example, your patient may believe their health is under the control of outside influences rather than being caused by their own actions. These patients are said to have an external locus of control[22] . They may feel they are immune to cancer (e.g. “it couldn’t happen to me” belief) or that their health is the responsibility of healthcare professionals (e.g. “I will wait until my next mammogram and ask them about this lump”). They may have progressed from this to the start of the change cycle and feel they should do something about their symptom but have not done so yet.Box 3: Barriers to seeing the GP about worrying symptoms

- Embarrassment;

- Perception of wasting the GP’s time;

- Fear;

- Worries about what the doctor might find;

- Difficulty in making an appointment;

- Apparent immunity (e.g. “it couldn’t happen to me” belief);

- Responsibility is that of the healthcare professional (e.g. “my doctor has not said anything”);

- Low perceived risk (around 2–3% of cancer is caused by inherited genes);

- Ignorance — one in five people remain unaware of mouth cancer[14] .

Box 4: Conversational tips

- Encourage conversation by displaying relevant materials, such as those explaining how lifestyle decisions (e.g. alcohol, smoking, obesity, diet and sun exposure) contribute to cancer [23] ;

- Think about how you would feel if your patient developed cancer from a lifestyle choice that you could have warned them about;

- Myth busting — there is no evidence to show that mobile phones, deodorants and stress increase the risk of cancer or that ‘superfoods’ prevent or cure cancer[24] ;

- You do not need to have answers; help is readily available from the voluntary sector. Ensure you use reliable sources of information, such as NHS Choices, Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support. Be aware of the variety of tumours patients can have; there is a range of reliable sources of information and support for patients with different cancers;

- Work with pharmacy colleagues to identify main points to raise when having conversations about cancer. Try questions that do not mention cancer[6] , such as:

- What does your doctor say about that?

- How long have you had it?

- What has changed?

- What is it you are worried about?

Screening processes

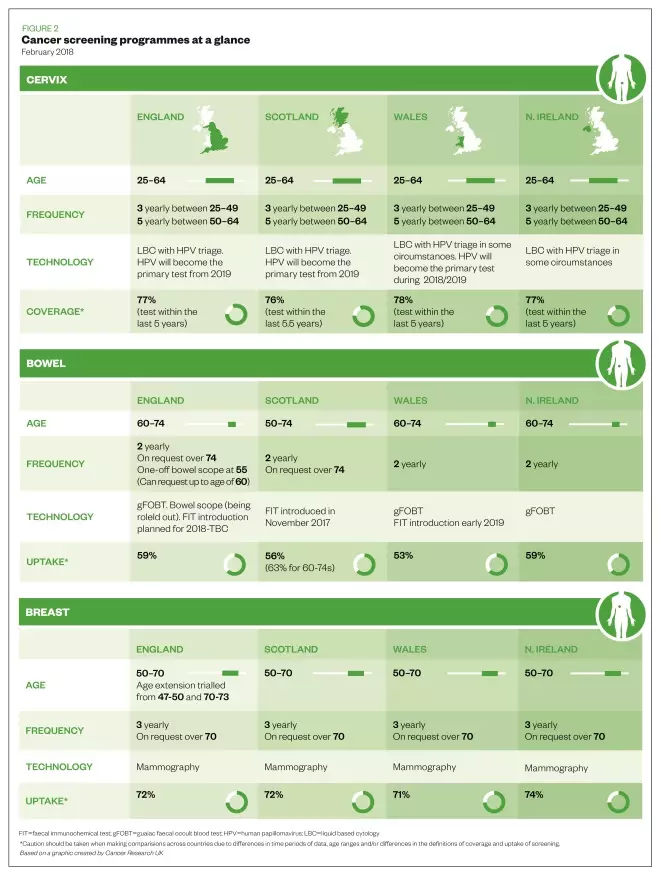

National screening programmes are offered to several age groups for breast, bowel and cervical cancer (see Figure 2)[25] . Patients should be encouraged to attend screening. The CRUK ‘Talk cancer’ team highlights that some screening processes prevent cancer by detecting abnormal cells before they develop into cancer, including cervical cancer screening and the new bowel scope screening process.

Figure 2: Cancer screening programmes at a glance

Source: Cancer Research UK

- Bowel cancer and the ‘Blood in pee’ campaign

- ‘Suspected cancer guidelines for pharmacists’

- ‘Talk cancer’ (a free online course) run by Cancer Research UK

- Macmillan Cancer Support primary care resource pack

- ‘Accelerate, coordinate, evaluate programme: Pharmacy training for early diagnosis of cancer’

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s quick reference guides:

References

[1] Lewis J. How to support cancer patients in community pharmacies. Pharm J 2017. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20202377

[2] Cancer Research UK. Spot cancer early. 2016. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-symptoms/spot-cancer-early (accessed October 2018)

[3] NHS England. Cancer strategy implementation plan. 2016. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/strategy/ (accessed October 2018)

[4] Jones D & Macleod U. Recognition and referral of cancer symptoms in primary care. Practice Nursing 2015;26(9):426–431. doi: 10.12968/pnur.2015.26.9.426

[5] Public Health England. Be clear on cancer. 2017. Available at: https://campaignresources.phe.gov.uk/resources/campaigns/16-be-clear-on-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[6] Badenhorst J, Husband A, Ling J et al. Do patients with cancer alarm symptoms present at the community pharmacy? Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22(Suppl 2):23–106. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12146

[7] Gill J, Sullivan R & Taylor D. Overcoming cancer in the 21st century [lecture/presentation]. UCL School of Pharmacy. January 2015.

[8] Cancer Research UK, NHS England & Macmillan. Pharmacy training for early diagnosis of cancer. Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate (ACE) Programme. 2015. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/ace_pharmacy_training_report_june_2017_update.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[9] NHS England. Making every contact count. 2016. Available at: http://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/ (accessed October 2018)

[10] National Pharmacy Association. The whites of your eyes. 2017. Available at: https://www.npa.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Whites-of-your-eyes-article-June-2017.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[11] Royal Society for Public Health. Healthy Living Pharmacy. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-services/registration-healthy-living-pharmacies-level1.html (accessed October 2018)

[12] Randall M & Neil K. The patient: Signs and symptoms. Disease Management 2016. Pharmaceutical Press. London. P4.

[13] Training Matters. Getting the most out of WWHAM. 2015. Available at: https://www.tmmagazine.co.uk/getting-the-most-out-of-wwham (accessed October 2018)

[14] Pharmacy Magazine. Oral health: could it be cancer? 2018. Available at: https://www.pharmacymagazine.co.uk/could-it-be-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[15] Schroeder K, Chan W & Fahey T. Recognizing red flags in general practice. InnovAiT 2011;4(3):171–176. doi: 10.1093/innovait/inq143

[16] Devon Local Pharmaceutical Committee. Suspected cancer guidelines — quick reference guide for pharmacists. 2017. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/devon-lpc/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/07/Suspected-Cancer-Guidelines-for-pharmacists-docx.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[17] National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. Routes to diagnosis: exploring emergency presentations. 2013. Available at: http://www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/routes_to_diagnosis_exploring_emergency_presentations (accessed October 2018)

[18] Cancer Research UK. Spotting cancer early saves lives. 2017. Available at: https://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/publication-files/Early%20Diagnosis%20Female%20WEB.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[19] Macmillan Cancer Support. Rapid referral guidelines. 2015. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/aboutus/health_professionals/pccl/rapidreferralguidelines.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[20] Power E & Wardle J. Change in public awareness of symptoms and perceived barriers to seeing a doctor following Be Clear on Cancer campaigns in England. Br J Cancer 2015;112(1):S22–S26. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.32

[21] Cancer Research UK. Delay kills. 2012. Available at: www.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/…/cr_085096.pdf (accessed October 2018)

[22] Rotter JB. Social learning and clinical psychology. NY: Prentice-Hall. 1954.

[23] Cancer Research UK. Causes of cancer. 2012. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer (accessed October 2018)

[24] Cancer Research UK. Cancer controversies. 2015. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/cancer-controversies (accessed October 2018)

[25] Cancer Research UK. Screening for cancer. 2018. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/screening (accessed October 2018)