Science Photo Library

Oral health has an important role in the general health and wellbeing of individuals, however, significant inequalities in oral health exist across England[1]

. Many patients are poor at attending dental appointments, yet frequently visit their community pharmacy and are open to a pharmacy-based oral health intervention[2]

. Guidelines on the delivery of oral health messages, such as Public Health England’s (PHE’s) ‘Delivering better oral health’ toolkit, are widely accessible and community pharmacies are encouraged to adopt these into regular practice[1]

.

This article will discuss how preventative care messages can be delivered in community pharmacy for three oral health problems: dental caries, periodontal disease and oral cancer. These conditions are usually associated with some modifiable risk factors and can have significant long-term implications for patients. However, it should be noted that the recommendations made here are designed to act as preventative and supportive management in conjunction with the patient seeking a professional opinion from a dentist.

Dental caries

Dental caries, also known as tooth decay, is the most widespread non-communicable disease according to the World Health Organization[3]

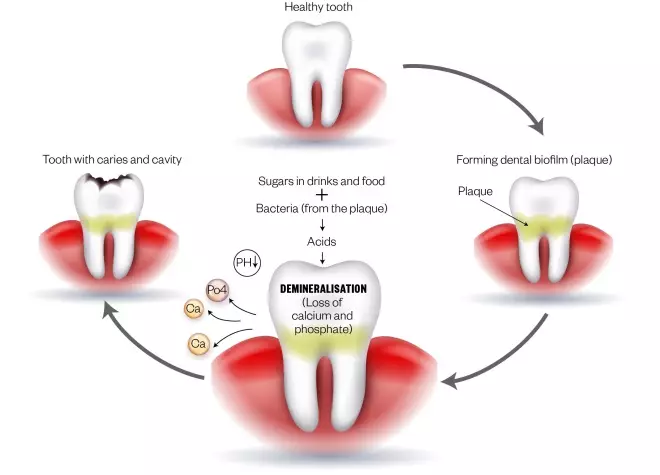

. Dental caries develops when bacteria in the mouth metabolise sugars to produce acid that demineralises the hard tissues of the teeth (i.e. the enamel and dentine; see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tooth with caries

Source: Mclean / Shutterstock.com

Bacteria in the plaque metabolise sugars to produce acid, which can break down the surface of the tooth, causing holes known as caries

Early stages of dental caries often present without any symptoms, however, as the disease progresses, it may result in toothache or tooth sensitivity, or brown/black spots on any surface of a tooth[4]

. Severe cases result in infection and tooth loss.

Risk factors

The following factors increase the risk of dental caries development and progression:

Diet

The term “free sugars” excludes sugars naturally present in milk products, whole fruits, vegetables and grains. Patients who eat foods that contain free sugars (e.g. cakes, biscuits, sweetened cereals, honey, syrups and preserves) and drink sugary drinks (e.g. fizzy drinks) are at an increased risk of dental caries. Fruit juices and smoothies also contain free sugars and often have a high acidic content, which raises the risk of dental caries and erosive toothwear, respectively[1]

. Dried fruit especially increases the risk of dental caries, as this can stick readily to the tooth surface. The overall consumption of these foods and drinks should be reduced; ideally, no more than 5% of the energy an individual consumes should come from free sugars.

Medically compromised patients

Some patients may find it challenging or unsuitable to maintain a dietary intake as recommended in PHE’s ‘Eatwell Guide’[1]

. Patients requiring nutritional supplements may need specialised drinks to maintain their calorie input which can have a high free sugar content, putting them at risk of dental caries. Furthermore, certain liquid medicines can also have a high sugar content and sugar-free alternatives may not be available.

Patients with reduced or diminished salivary flow (e.g. following radiotherapy to the head and neck) are also at increased risk of developing dental caries. Certain salivary replacement products may contain sugar, therefore, these products should only be offered to patients without natural teeth.

Developmental conditions

Developmental defects of the teeth (e.g. an enamel defect such as molar incisor hypomineralisation) may render the tooth surface more susceptible to breakdown and dental caries.

Prevention

Dental caries are largely preventable. General advice for both children and adults is as follows:

- As soon as the first tooth erupts, brushing should be commenced at least twice daily — last thing at night and at least on one other occasion;

- Where medicines are given frequently or long term, sugar free medicines should be used where available[1]

.

The following general advice will help to prevent dental caries in children:

- Parents/carers should supervise teeth brushing until the age of seven years old;

- Sugar should not be added to weaning foods or drinks[1]

.

Promote fluoride therapy

It is important to promote remineralisation of the enamel surface of the tooth through fluoride therapy. Fluoride is a naturally occuring mineral that can be found in the UK public water supply, but is also added to top up levels in the supply in some areas. It is also in toothpaste to help strengthen tooth enamel, making teeth more resistant to acids. There are a range of toothpastes available and the recommended level of fluoride varies for different age groups (see Table 1). Dentists can also apply fluoride varnish or gel to the teeth at regular intervals during the year[1]

.

| Table 1: Recommended levels of fluoride per age group | |||

| Less than three years old | Three to six years old | Seven years and older | |

| Frequency | Brush twice daily | Brush twice daily | Brush twice daily |

| Toothpaste | Smear of toothpaste containing at least 1,000ppm fluoride | Pea-sized amount of toothpaste containing >1,000ppm fluoride | Toothpaste containing 1,350–1,500ppm fluoride |

| Patients identified as ‘high risk’ of dental caries by their dentist or those with existing dental caries | N/A | Toothpaste containing 1,350—1,500ppm fluoride |

|

| Other advice |

| N/A | N/A |

Source: NHS | |||

All patients should be advised to spit out toothpaste and to not rinse with water or mouthwashes (including fluoride rinses) immediately after toothbrushing, as these can wash away the concentrated fluoride in the remaining toothpaste, reducing its preventive effects[1]

.

Provide dietary advice

Advise patients that dental caries are the result of lifelong exposure to free sugars, therefore, even a small reduction in free sugar intake in childhood is of significance in later life[1]

. To also reduce risk, advise patients that it is better to consume foods that contain free sugars as part of a main meal, and to avoid snacking on them, since it is the frequency of consumption of free sugars that renders the teeth vulnerable to damage (see Figure 1)[1]

.

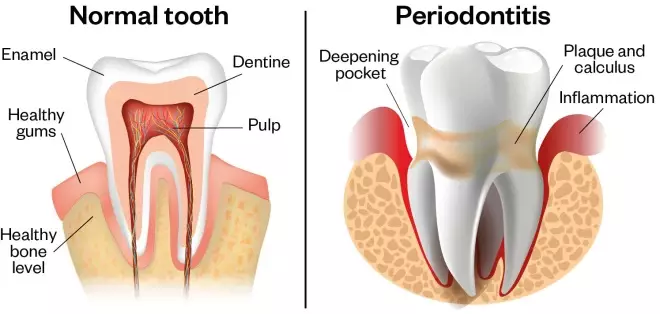

Periodontal disease

Also known as gum disease, periodontal disease is caused by bacteria in dental plaque. To eliminate the bacteria, the immune system releases substances that cause inflammation, resulting in swollen and bleeding gums (see Figure 2). If left untreated, periodontal disease can lead to bad breath, wobbly teeth and, ultimately, loss of teeth[5]

.

An association between periodontal disease and Alzheimer’s disease has been suggested, although no causal link has yet been proven[6]

.

Figure 2: A normal tooth compared with one with periodontitis

Source: Shutterstock.com

Periodontal disease is caused by bacteria in dental plaque, the sticky substance that forms on the teeth a couple of hours after they have been brushed. The build up of plaque can lead to the inflammation of the gums

Risk factors

Risk management and prevention are essential in slowing the progression of the disease.

Poor oral hygiene

The presence of plaque on teeth is considered a significant risk factor. If adequate plaque control is not achieved, periodontal disease will progress. Calculus (also known as tartar) is a form of hardened dental plaque that may act as a physical obstruction to oral hygiene measures and can create an environment for further plaque accumulation[7]

.

Tobacco use

Smoking increases the risk of periodontal disease, reduces the benefits of treatment and increases the chance of tooth loss

[7]. E-cigarettes and/or inhaled nicotine may contribute to the pathogenesis of periodontal disease, however, limited studies into the use of these products mean that the long-term health implications are unclear[5],[8]

Poorly controlled diabetes increases the risk of periodontal disease development. Furthermore, wound healing is adversely affected by diabetes, therefore, treating patients with diabetes and periodontal disease is more difficult[5]

.

Hormonal changes during pregnancy can make gums more susceptible to plaque (pregnancy gingivitis)[9]

, although this normally reverts after parturition[5]

.

Side effects of medicines

There are several types of medicines known to affect periodontal health[5]

. Many medicines are reported to cause dry mouth, but it is most commonly seen with antidepressants and antihistamines. Gingival enlargement is a side effect of calcium channel blockers for cardiovascular disease (e.g. nifedipine[10]

).

Prevention

Provide oral hygiene advice

Toothbrushing should be commenced as soon as the first primary tooth erupts in children[1]

. No brushing technique has been shown to be superior to another, but patients may find plaque disclosing tablets will help to identify areas of plaque accumulation[1]

. Patients should be made aware that dental implants require the same level of oral hygiene as natural teeth because the supporting structures (e.g. the gums) are still susceptible to disease[5]

.

Effective twice-daily brushing is considered more important than the type of toothbrush used. There is limited evidence that powered oscillating rotating toothbrushes are more effective for plaque control compared with manual toothbrushes[1]

. However, electric toothbrushes can be an incentive for brushing in patients with poor compliance and in children, and may be beneficial for patients with reduced manual dexterity[1]

.

The toothbrush head should be replaced every three months or earlier if the bristles are frayed, otherwise plaque removal will be ineffective[1]

.

There is limited evidence that fluoride toothpaste containing triclosan and a copolymer reduces plaque and gingival inflammation more than toothpastes that contain fluoride only[1],[5]

Interdental cleaning aids

In addition to toothbrushing, interdental cleaning aids (e.g. floss or interdental brushes) should be used daily between the teeth and below the gum line to achieve effective plaque control. Interdental brushes are more effective for larger spaces between teeth than dental floss or tape. The brush should be a ‘snug’ fit in the interdental space, therefore, most patients will require more than one size of brush to adequately access all the interdental spaces around their mouth. Patients with dental bridges or orthodontic appliances may require specialised products (e.g. super floss)[1]

.

Provide smoking cessation advice

Explain that non- and ex-smokers are less likely to get periodontal disease and prematurely lose their teeth than smokers. Patients who would like to stop smoking should be signposted to smoking cessation services.

Provide other healthcare advice

Patients with diabetes are advised to maintain levels of HbA1c of 6.5% (48mmol/mol) or lower[1]

and should be referred to their GP if their diabetes is uncontrolled.

If the patient’s periodontal disease is linked to medicine they are taking, refer them to their GP to see if they can be switched to an alternative drug.

Oral cancer

According to the NHS, oral cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world, but it is less common in the UK, with around 6,800 people diagnosed each year (around 2% of all cancer diagnoses)[11]

.

Mouth cancer is usually painless in its early stages; therefore, most tumours are not detected until the cancer is advanced as this is when a patient usually seeks help with increasing discomfort.

The following signs are considered significant and patients presenting with the following should be advised to seek an urgent assessment from their GP or dentist:

- Unexplained ulceration in the oral cavity lasting for more than three weeks;

- A persistent and unexplained lump in the neck;

- A lump on the lip or in the oral cavity;

- A red and white patch (erythroleukoplakia) or red patch (erythroplakia) in the oral cavity[12]

.

If the patient is acutely unwell, urgent advice should be sought from the local hospital.

Risk factors

Just under half of oral cancers are associated with potentially modifiable risk factors, which include:

- Smoking;

- Alcohol consumption;

- Chewing tobacco or betel quid (areca nut);

- Human papillomavirus infection;

- Genetics.

Prevention

Stop smoking

At least 50 different diseases are caused by tobacco use, including various cancers, ischaemic heart disease, strokes and chronic lung disease. The most significant effects of tobacco use on the oral cavity are oral cancers and pre-cancers, increased severity and extent of periodontal diseases, tooth loss and poor wound-healing post-operatively[5]

. Patients should be referred to smoking cessation services and informed that they may experience a transient increase in bleeding from the gingivae on smoking cessation as the oral vascular supply returns to normal and the masking effects of smoking are removed[5]

.

Reduce alcohol intake

Research shows that around 30% of mouth and oropharyngeal cancers are caused by drinking alcohol. Smoking and drinking together further increases the risk of cancer[13]

.

Alcohol consumption can be categorised as follows:

- Lower risk – This implies that no level of alcohol consumption is completely safe. The context can determine the level of risk (e.g. drinking and driving). The Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines advise that lower risk is not regularly exceeding 14 units per week[14]

; - Increasing risk – For both men and women, increasing risk is regularly drinking more than 14 units per week[14]

; - Higher risk – Higher risk drinking means regularly drinking more than 35 units per week for women and more than 50 units per week for men[14]

; - Binge drinking – drinking too much or too quickly[1],[5],[14],[15]

.

All patients should be advised that reducing alcohol intake will reduce their risk of cancer. High-risk drinkers should be signposted to alcohol support services.

Safeguarding

The British Society of Paediatric Dentistry define dental neglect in children as “…the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic oral health needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of a child’s oral or general health or development.” Dental neglect can occur in isolation or may indicate a wider picture of maltreatment[16]

. If there are safeguarding concerns about a child, seek advice from local children’s services[17]

.

Useful resources

- Department of Health. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf

- The Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines. 2016. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf

- Public Health England. Smokefree and smiling: Helping dental patients to quit tobacco. 2014. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/288835/SmokeFree__Smiling_110314_FINALjw.pdf

References

[1] Department of Health. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[2] Sturrock A, Cussons H, Jones C et al. Oral health promotion in the community pharmacy: an evaluation of a pilot oral health promotion intervention. Br Dent J 2017;223(7):521–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.784

[3] The World Health Organization. Sugars and dental caries. 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/oral_health/publications/sugars-dental-caries-keyfacts/en/ (accessed February 2020)

[4] NHS Choices. Tooth decay. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/tooth-decay/ (accessed February 2020)

[5] British Society of Periodontology. The Good Practitioner’s Guide to Periodontology. 2016. Available at: https://www.bsperio.org.uk/publications/good_practitioners_guide_2016.pdf?v=3 (accessed February 2020)

[6] Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Science Advance 2019;5(1):eaau333. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3333

[7] NHS Choices. Gum disease. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gum-disease/causes/ (accessed February 2020)

[8] Javed F, Kellesarian SV, Sundar IK et al. Recent updates on electronic cigarette aerosol and inhaled nicotine effects on periodontal and pulmonary tissues. Oral Diseases 2017;23(8):1052–1057. doi: 10.1111/odi.12652

[9] NHS Choices. Teeth and gums in pregnancy. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/teeth-and-gums-pregnant/ (accessed February 2020)

[10] BNF. Nifedipine. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/nifedipine.html (accessed February 2020)

[11] NHS Choices. Mouth cancer. 2016. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/mouth-cancer/ (accessed February 2020)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Head and neck cancers - recognition and referral. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/head-and-neck-cancers-recognition-and-referral (accessed February 2020)

[13] Cancer Research UK. Mouth and oropharyngeal cancer - Risks and causes. 2018. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/mouth-cancer/risks-causes (accessed February 2020)

[14] The Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines. 2016. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[15] Public Health England. Smokefree and smiling: Helping dental patients to quit tobacco. 2014. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/288835/SmokeFree__Smiling_110314_FINALjw.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[16] Harris JC, Balmer RC & Sidebotham PD. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on dental neglect in children. Int J Paed Dent 2018;28:e14-e21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.00996.x

[17] British Dental Association. Child protection and the dental team: an introduction to safeguarding children in dental practice. 2016. Available at: https://bda.org/childprotection/Resources/Documents/Childprotectionandthedentalteam_v1_4_Nov09.pdf (accessed February 2020)