DR P. MARAZZI / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Learning objectives

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand when biologics are used;

- Know the process for initiating a biologic for any condition;

- Know how to support patients before, during and after starting a biologic.

Biologic medicines are prescribed for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis[1–5]. More recent indications include severe migraines, age-related macular degeneration and coronavirus infection[6].

A biologic is a protein molecule that attaches to and deactivates inflammatory cells. Biological medicines (e.g. monoclonal antibodies, growth hormone and insulin) are produced in or derived from living systems and are referred to as originator or reference products[7]. The size and complexity of biological medicines, as well as the way in which they are produced, may result in a degree of natural variability in molecules of the same active substance, particularly in different batches of the medicines[7].

The active substance of a biosimilar and its reference medicine is essentially the same biological substance; however, just like the reference medicine, the biosimilar has a degree of natural variability. When approved, biosimilars are shown to have comparable quality, safety and efficacy profile to the originator product. Biosimilar medicines introduced to the UK market are authorised by the European Medicines Agency (EMA)[8]. Biologic and biosimilar medicines are currently prescribed and monitored in a secondary care setting and are often high cost[9,10].

Biologics are now commissioned to treat both severe and moderate disease. Since the expiry of some patents, such as infliximab, etanercept, rituximab, and adalimumab, the manufacture of biosimilar medicines has reduced the cost of procurement of these medicines[11]. This has led to better access to biologics for patients and is part of an ongoing focus for the pharmacy medicines optimisation strategic objectives on a local, regional and system-wide level[2]. The Medicines Value Programme — set up by NHS England to optimise health outcomes from medicines and reduce medicines spending — has allowed the realisation of these savings. The use of biosimilars allows optimisation of choice of medicine through balancing various factors; for example, efficacy, cost, waste reduction, patient acceptability and availability[11].

Current NHS practice follows National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, where evidence is appraised and guidance provided in the form of a technology appraisal or NHS England commissioning policy on the use of biologics. This is aligned with commissioning agreements, which informs clinicians and patients of biologic funding and indications. Within the hospital setting, best practice for prescribing these medicines is agreed in a multidisciplinary setting with support from a pharmacist.

This article will outline the process of initiating a biologic or biosimilar medicine, with consideration for the mechanism of action and indication, the clinical pathway and how to support and communicate with the patient during a consultation before, during and after commencing on a biologic or biosimilar medicine in an outpatient setting.

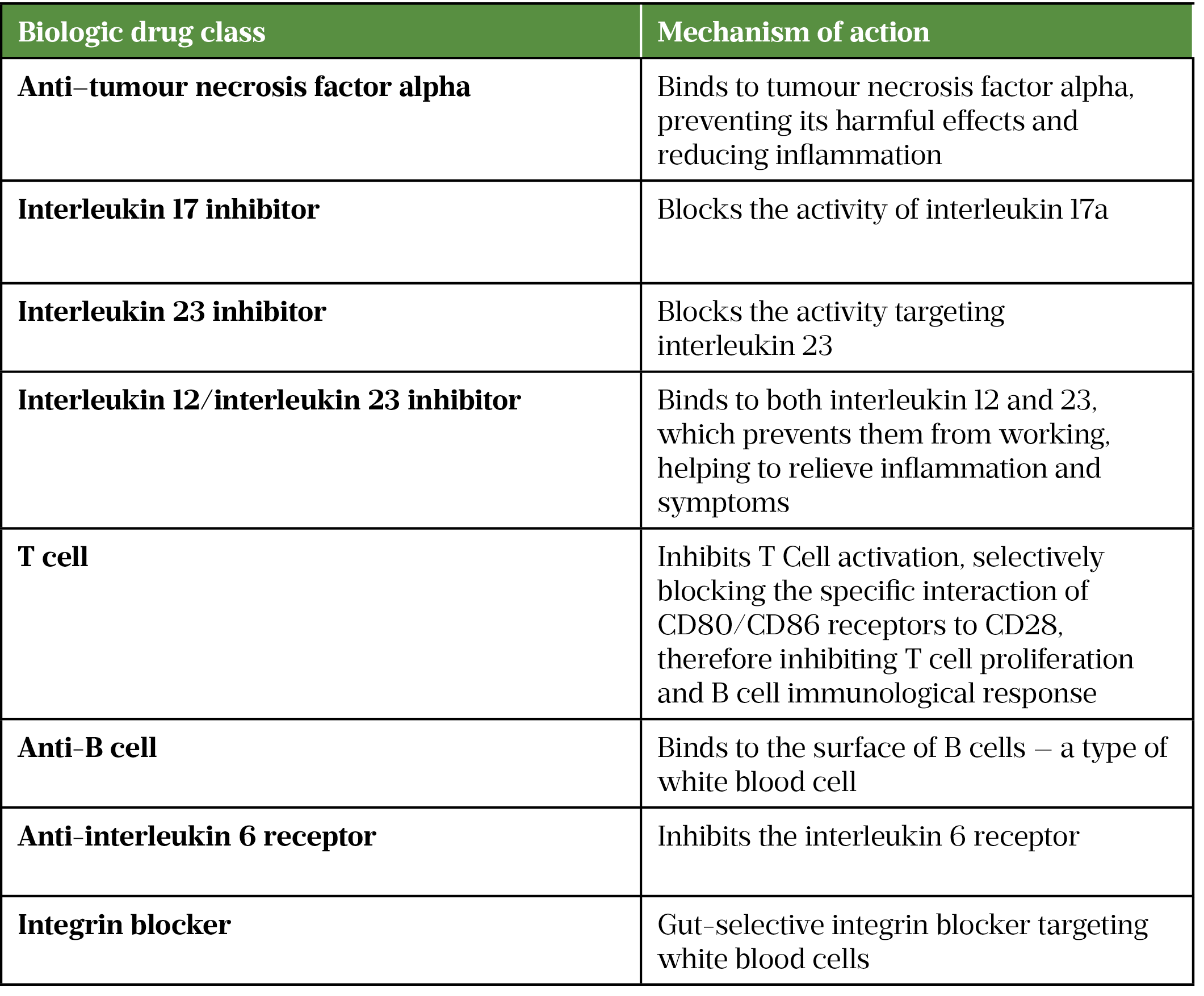

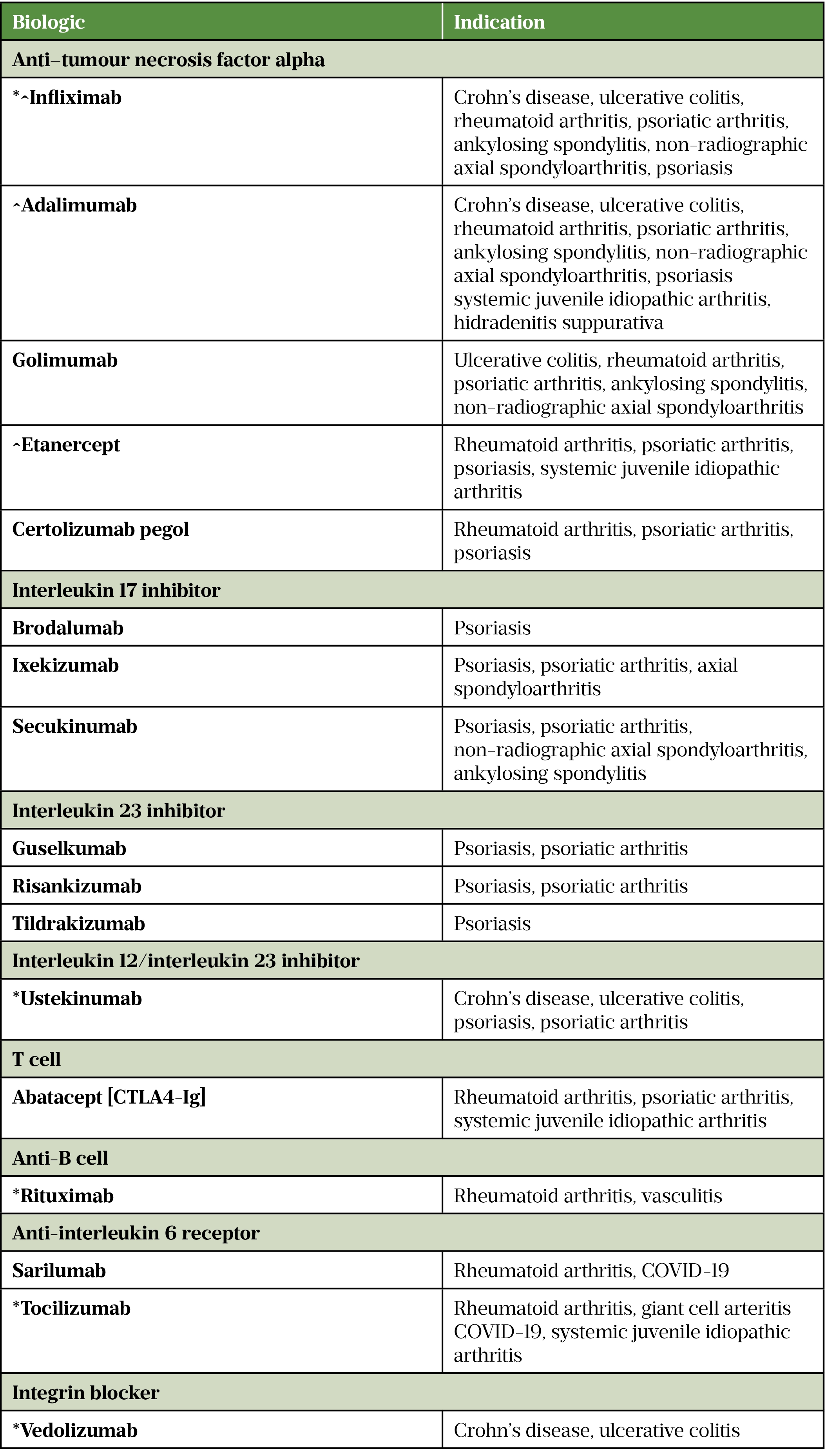

The tables below include examples of biologics used in autoimmune diseases[12–28].

* Intravenous and subcutaneous formulations

^ Biosimilar medicine available

Process for initiating a biologic for any condition

Relevant clinical policy and guidelines should be consulted for each disease and indication when considering the initiation of a biologic. It is important to understand which indications are funded and the licensed medicines available.

The following steps should be followed when initiating a biologic:

- Confirm that the considered biologic medication is on the local formulary and commissioning pathway;

- Ensure a route of supply has been established (e.g. outpatient pharmacy or homecare);

- Each hospital will have a process to ensure the medication can be prescribed (e.g. paper prescriptions or via electronic prescribing systems);

- Every intravenous and subcutaneous biologic/biosimilar must be prescribed by brand and brand of choice is guided by trust policy;

- Ensure that the batch numbers and expiry dates can be recorded either on paper prescription or electronically on the medication administration record when administering biologics and biosimilars on site;

- Ensure all adverse drug reactions are reported to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency via the yellow card scheme;

- If homecare is the selected route, purchase orders need to be raised and invoices processed by a multidisciplinary pharmacy team (e.g. pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and pharmacy assistants);

- Invite patient to a biologics consultation clinic with a specialist nurse or pharmacist;

- Demonstrate administration of medication as each device differs;

- Obtain consent verbally or written from patient to proceed with the consultation, prescribing of the medication and to pass on personal details to the homecare company via a signature on a consent or registration form if this is the chosen route of supply. This should be asked for clearly and documented in the patient’s medical notes;

- Arrange pre-screening of the necessary blood tests and investigations, which include full blood count, liver function tests, creatinine, C-reactive protein, urea and electrolytes, varicella zoster virus, HIV, hepatitis B and C, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and chest X-ray. Results should be confirmed as satisfactory before medication is prescribed;

- At present, the completion of Blueteq (commissioning software/paperwork) is required to ensure the patient has received funding for their agreed medication to enable reimbursement. From July 2022, the budgets of the clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and primary care, as well as many of the specialised commissioning budgets, will come under a ‘single-pot’ led by integrated care systems, which may change the way CCGs account for use of high-cost drugs[29,30].

Other considerations for the initiation of a biologic are the resources for clinical screening, as well as clinical review of the patient post initiation of treatment.

Clinical pathway: how to choose any biological medicine

- Patient case is discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting, present are specialist consultant(s), nurses, pharmacist, psychologist, dietician for nutritional support and advice (e.g. for patients with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]) and physiotherapists (e.g. for rheumatology patients);

- A detailed review of drug history, including past medications tried or failed, allergy status and any over-the-counter or herbal medicines and vitamins, medical history for specific conditions and an updated disease activity score for disease severity as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence or local guidance. For example, the DAS28 activity score is used to assess rheumatoid arthritis disease severity. Any trends or changes in a patient’s symptoms, home life, lifestyle and mental health should also be explored. Any potential polypharmacy issues should be addressed;

- Refer to local agreed pathway, if in place, to select biologic therapy and consider if the patient has any other comorbidities that would be covered by a selection of medication (see Table)

- Consider potential disease–drug interactions, as well as drug–drug interactions (e.g. avoid secukinumab in IBD patients);

- All biologics by nature of their composition require fridge storage between 2–8°C;

- All biologics will require administration via subcutaneous injection via a pre-filled pen, pre-filled syringe or vial;

- Biologics have varied frequencies of administration (e.g. every 2 weeks, every month, every 8 weeks and every 12 weeks);

- Biologics are available as intravenous infusions and via subcutaneous route for self-administration;

- Consideration if patient is complex and requirement to access drug levels to support clinical review, dose titration and decision making (e.g. infliximab and adalimumab);

- Choice of biologic should continue to be guided by patient need, patient characteristics, clinician recommendation and local service delivery;

- In the absence of a specific clinical need, the ‘most cost-effective drug first’ principle will apply, but cost alone should not be the only principle to guide prescribing of biologic therapies. Other considerations include:

- When intravenous and subcutaneous versions of medication are available, consider the capacity in infusion units and whether the intravenous version is most appropriate for patient (e.g. compliance reasons, inability to self-administer and if clinician and patient jointly feel it is appropriate);

- Consider patient factors, such as latex-containing medicines, suitability of devices and level of manual dexterity, frequency of administration, route and adherence to the drug;

- Selected homecare schemes include enhanced nursing support, which may or may not be appropriate for the patient population; liaise with the homecare pharmacy team for more information locally[31–36].

Schedule patients in for review appointments three months after initiating biologic treatment in line with NICE guidelines (or following local hospital guidance), then every six months, and annual review is required[1–5].

Patient-centred care

The process and clinical pathway are critical to successful treatment but will only be effective if patients are engaged in discussions about all aspects of treatment. Patient’s values, beliefs and preferences will determine the effectiveness of individualised treatment plans, supported by clinician judgement and expertise. There are unique challenges to initiation and maintenance of biologics and biosimilars, and concordant conversations to support optimal adherence are a critical step in the biologics journey. Examples of areas that concern patients, in relation to change, include fear of the implication of change on disease control (especially if person is stable on current medicines), fear of potential side effects of a new medication and concern about how well a new medicine has been tested (i.e. feeling like a “guinea pig”). In addition, some patients may believe that biosimilars being cheaper than the originator medicine may be less effective. Even when a patient agrees to moving to a biosimilar or alternative treatment, support may be required to manage different dose, route, timing, storage, formulation and how the medication will fit in to the patient’s life. Effective shared decision-making conversations are central to the Medicines Value Programme, balancing risks and benefits of medicines for the patient as well as from the clinician’s perspective[37].

Specific counselling points to consider when consulting with patients who are being switched to a biosimilar medicine include:

- Determining how much information the patient already knows and wants to know;

- If required, explaining the reasoning for switching to a biosimilar medicine and reassuring the patient that the clinical trials that are required for licensing must show that the medicine has been used in practice since 2006;

- Exploring any concerns if the patient has any;

- Reassuring the patient that they will be monitored after switching to the new medication in the same way as their current treatment, and encouraging any feedback in change in symptoms or side effects as you would when initiating any new therapy;

- Explaining any changes in the route of supply, if any, and ensuring they are comfortable about how to obtain the new treatment.

Effective consultations with patients before, during and after starting a biologic

Before initiation

Establish how the patient feels about having a conversation regarding changes to their medications or new medicines. If it is not a suitable time, then reschedule and decide which format is most convenient (e.g. phone, video, face to face).

Understand if the patient is ‘biologic naïve’ or if they have been prescribed a biologic in the past, to identify the correct level of information that the patient requires. Ask them how much they know and how much they would like to know about this medication.

Suggested questions to elucidate patient biologic experience and desired level of knowledge:

- To give you the information that is relevant to you, can you tell me what you already know about this medicine, and what it is that you are asking about?

- What, if anything, worries you?

- What are you hoping this medicine will do for you?

- What do you already know about making this change?

- What do you understand about why we are making this change?

Ensure to answer patient questions and not just impart the information that you feel is relevant. Ask permission to share important information with them verbally and be ready with alternative methods that are preferable to them (e.g. website, email, post, YouTube). They may prefer a link or written information because they feel they want to show their relatives or revisit information at a later date.

During initiation

Examples of clinical information to cover during consultation:

- The dosing of the medication to the patient and the duration of treatment;

- Any condition or drug-specific counselling points (e.g. ensure that the patient knows to give the brand name of the medication when asked for a drug history and preoperatively);

- Obtain consent to take infection-screening blood tests (e.g. HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis B and C) and any other required tests before starting biologic (e.g. bloods and x-rays);

- Vaccinations, if required, prior to commencing treatment. Address any vaccine concerns as well as the contraindication of live vaccines;

- Information related to family planning (e.g. pregnancy, breastfeeding and sperm health) where applicable and offer signposting (see ‘Useful resources‘);

- Adherence-focused counselling (e.g. discussing frequency of administration, potential barriers, such as self-administration, pain in joints and design of the device, which might inform the medication choice, difficulties travelling to the infusion unit or getting time off work to attend infusion appointments);

- Condition-specific and drug-specific monitoring requirements while on treatment, as well as annual review;

- Common side effects — especially depression in anti-tumour necrosis factors — and how to manage this.

Risks and benefits should also be discussed — for example, the potential impact on the patient life (including side effects and understanding of cancer risk, etc.). Some patients will need the opportunity to go away and think, and it is important to offer this.

Supporting patients with medicine supply — questions to ask

- How will you get the supply of medication?

- Will this be supported by a homecare company?

- What do you know about homecare?

- Would it be helpful for you to have a leaflet, or should I explain?

This conversation enables and maintains choice and control with the patient, which supports people in taking responsibility for their own care[38].

Best practice points

- Work closely and keep an open dialogue within the multidisciplinary team to ensure collaboration and joined up working;

- Work collaboratively and keep an open dialogue with the clinical commissioning group colleagues (soon to be integrated care systems);

- Horizon scan and plan for budget setting, resource and pathways for new medications coming to market;

- Ensure planning with operations and finance colleagues within pharmacy and the clinical teams to ensure the resource to deliver an expanding service is commissioned;

- Remember that each patient is different and brings with them various concerns, past experience and level of knowledge, so each consultation cannot be approached in the same way;

- Ensure joined up working between hospital, community pharmacy and primary care colleagues (i.e. provision of information if patient consents).

Useful resources

Crohn’s and Colitis UK website: crohnsandcolitis.org.uk

Psoriasis association leaflets and information sheets: psoriasis-association.org.uk

Versus arthritis: versusarthritis.org

National Rheumatoid arthritis society: nras.org.uk

- The tables in this article were updated on 11 July 2022 to clarify the information included in them

- 1Crohn’s disease: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng129 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 2Ulcerative colitis: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng130 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 3Smith CH, Yiu ZZN, Bale T, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2020: a rapid update. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:628–37. doi:10.1111/bjd.19039

- 4Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 5Tucker L, Allen A, Chandler D, et al. The 2022 British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis with biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs. Rheumatology. 2022. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keac295

- 6Biologics: A new road into the future of medicine. Optometry Times. 2021.https://www.optometrytimes.com/view/biologics-a-new-road-into-the-future-of-medicine (accessed Jul 2022).

- 7Standards for biological medicines — understanding them and how they make a difference. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2017.https://www.gov.uk/government/news/standards-for-biological-medicines-understanding-them-and-how-they-make-a-difference (accessed Jul 2022).

- 8What is a biosimilar medicine? NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2019.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/what-is-a-biosimilar-medicine-guide-v2.pdf (accessed Jul 2022).

- 9Medicines Optimisation Clinical Reference Group. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/medicines-optimisation/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 10Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 11Medicines Value Programme. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/medicines-2/value-programme/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 12Infliximab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/infliximab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 13Adalimumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/adalimumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 14Golimumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/golimumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 15Etanercept. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/etanercept/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 16Certolizumab pegol. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/certolizumab-pegol/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 17Brodalumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/brodalumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 18Ixekizumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/ixekizumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 19Secukinumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/secukinumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 20Guselkumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/guselkumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 21Risankizumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/risankizumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 22Tildrakizumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/tildrakizumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 23Ustekinumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/ustekinumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 24Abatacept. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/abatacept/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 25Rituximab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/rituximab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 26Sarilumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/sarilumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 27Tocilizumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/tocilizumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 28Vedolizumab. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/vedolizumab/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 29Holroyd CR, Seth R, Bukhari M, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology biologic DMARD safety guidelines in inflammatory arthritis—Executive summary. Rheumatology. 2018;58:220–6. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key207

- 30Integrated NHS finances: what do they mean for High Cost Drugs? Wilmington Healthcare. 2021.https://wilmingtonhealthcare.com/integrated-nhs-finances-what-do-they-mean-for-high-cost-drugs/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 31Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and abatacept for treating moderate rheumatoid arthritis after conventional DMARDs have failed. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta715/chapter/1-Recommendations (accessed Jul 2022).

- 32Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 33Cosentyx 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic medicines compendium. 2022.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3669/smpc (accessed Jul 2022).

- 34Davies K. Risk Management of Medicines Stored in Clinical Areas: Temperature Control (Yellow Cover). Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2015.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/risk-management-of-medicines-stored-in-clinical-areas-temperature-control/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 35Treatment Options and Individualized Care. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. 2019.https://e-learning.ecco-ibd.eu/mod/data/view.php?id=523 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 36Biologics and JAK inhibitor pathway for moderate and severe rheumatoid arthritis. Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Clinical Commissioning Group. 2022.https://www.cambridgeshireandpeterboroughccg.nhs.uk/easysiteweb/getresource.axd?assetid=12841&type=0&servicetype=1 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 37Barnett NL, Flora K. Patient-centred consultations in a dispensary setting: a learning journey. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016;24:107–9. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000929

- 38Assessing, managing and monitoring biologic therapies for inflammatory arthritis. Royal College of Nursing. 2015.https://www.rcn.org.uk/-/media/royal-college-of-nursing/documents/publications/2015/february/pub-004744.pdf (accessed Jul 2022).

3 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thank you for your comprehensive article on a complex subject. May I point out however that abatacept, adalimumab and etanercept while good options for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA) are neither useful nor licenced for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) as erroneously stated in table 2. Tocilizumab is correctly identified as useful to treat sJIA ( as well as being useful for pJIA) . Please see SPC of these meds for further information.

Kind Regards

Clare Nash ( Specialist Pharmacist, Paediatric Rheumatology, Sheffield Children's Hospital)

Thank you for this very comprehensive account of a complex subject. May I just point out that the drugs abatacept, adalimumab and etanercept while useful drugs for polyarthritic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA) are unsuitable for (and not licensed to treat) systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis(sJIA) as claimed in table 2. Tocilizumab is however useful for sJIA Please see the relevant SPCs for further information.

Kind Regards

Clare Nash ( Specialist Pharmacist Paediatric Rheumatology Sheffield Children's Hospital)

Hi Clare. I am the Senior Editor at the PJ working on our learning and CPD provision. Thank you very much for highlighting this. I am looking into this with the authors of the piece and will make sure any necessary corrections are made.