This content was published in 2011. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

The “Outcomes strategy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma” was launched in July 2011 by the Department of Health, with the overall aim to drive improvements in outcomes for patients.1 Once implemented, it is expected to help people to avoid lung disease and lead longer and healthier lives. The strategy recognises the role of community pharmacy in supporting the management of people with respiratory disease through medicines use reviews and new pharmacy services.

In addition, the introduction of national target groups for MURs in England, under amendments to the NHS Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework, aims to ensure the service is provided to those who will benefit most. One of the target groups is patients with asthma or COPD.2 Both diseases have a major impact in the UK in terms of mortality and morbidity3 and the aim of MURs with these patients is to support them to take their medicines as intended, increase their engagement with their condition and medicines, and promote healthy lifestyles, in particular stopping smoking.

Potential and scope

Asthma and COPD are the commonest respiratory diseases seen in the UK.1 In England, figures for asthma range between three million and 5.4 million and it is estimated that around 835,000 people are registered with the NHS as having COPD (ie, mostly severe disease — many are undiagnosed).1 It is reported that on average every community pharmacy has over 500 patients with either a diagnosis of asthma or COPD.4

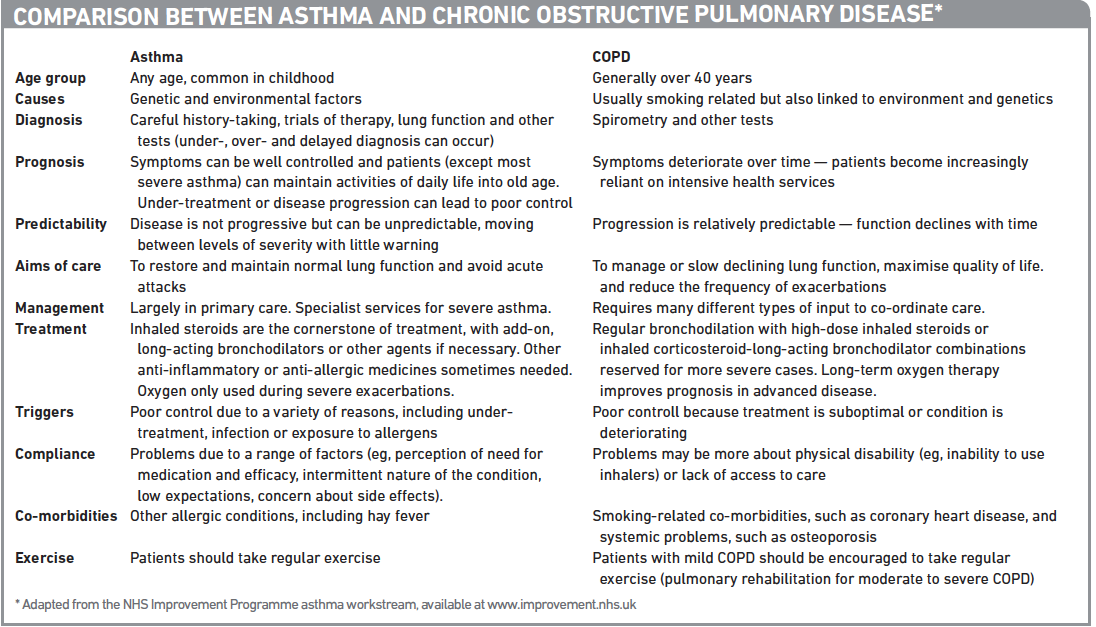

There are both similarities and differences between asthma and COPD. It is not always easy to differentiate between them (see later), but the wrong diagnosis and inappropriate treatment will result in patients not getting the care they need. Understanding the key differences and similarities is critical for reviewing related medicines, giving correct advice and having an effective discussion.

Both conditions are characterised by various degrees of airflow limitation, mucus and inflammation, and patients often have symptoms of coughing and wheezing. However, they differ in their pathophysiology, clinical presentation, lung function measurements and drug management.

Key points

- First-line maintenance therapy in asthma is inhaled corticosteroids. In COPD, bronchodilators are first-line.

- In asthma, compliance problems include perceived lack of efficacy and the intermittent nature of the condition. In COPD compliance problems may be more about physical disability.

- A distinction between the two diseases can be difficult in practice but asking patients for their diagnosis and being clear on the differences will help improve outcomes.

Different pathophysiology

Although asthma and COPD are both chronic inflammatory lung disorders, perhaps the most important difference between them is the nature of the inflammation that occurs. In asthma, inflammation is mainly caused by eosinophils, whereas in COPD neutrophils are involved.5 This is an important distinction because the nature of the inflammation affects the response to pharmacological agents: corticosteroids are effective against eosinophilic inflammation but largely ineffective against neutrophilic inflammation.

It is significant, however, to note that in exacerbations of COPD and asthma the patterns of inflammation become similar. In exacerbations of asthma triggered by viruses there can be increases in the number of neutrophils in addition to the proliferation of eosinophils. And in COPD exacerbations there may be an increase in eosinophil numbers.5 This helps to explain the prescribing of corticosteroids to COPD patients in order to manage an acute exacerbation or frequent exacerbations.6

In asthma, airway obstruction results from constriction of bronchial smooth muscle, airway hyper-reactivity to allergens, and inflammation accompanied by increased eosinophils and activated T-cells. In COPD, airway smooth muscle is not usually constricted and obstruction is associated mainly with mucus hypersecretion and mucosal infiltration by inflammatory cells, leading to cellular damage and the loss of alveolar structure. Furthermore, the cellular destruction and structural changes associated with COPD interfere with oxygenation and pulmonary circulation.

Different presentations

The classic initial clinical presentation of asthma is a young patient with recurrent, intermittent episodes of wheezing and coughing that may be accompanied by chest tightening or shortness of breath. Wheezing on breathing out is the classic symptom, but some patients present mainly with cough, especially at night.

Asthma is most often associated with onset during childhood and is common in those with a family history of atopy or asthma. Symptoms typically increase with exposure to allergens and triggers, such as pollen, dust mites and animal dander. In some cases, asthma symptoms disappear after childhood.7

In contrast, COPD is almost unknown in children and rare in adults under the age of 40 years.7 The classic presentation is an older current or ex-smoker with progressively worsening shortness of breath and possible cough and mucus production accompanied with decreasing physical activity (often assumed to be a sign of ageing). COPD is almost always associated with a long history of smoking, while asthma occurs in non-smokers as well as smokers.

Daily symptoms are present in only 27 per cent of people with asthma, whereas in COPD symptoms are more likely to be constant.8

Lung function measurements

Asthma and COPD are both suspected if a person reports characteristic symptoms. Diagnosis requires lung function tests.

Although both diseases are obstructive, in the classic patient with asthma, airway obstruction is reversible either spontaneously or with treatment, whereas in COPD obstruction is largely irreversible.

Asthma patients can often have symptoms when they have near-normal lung function. Most patients with COPD do not become symptomatic or aware of impairment until the FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) has fallen to about 50 per cent of the predicted value.

Patients with asthma do not normally experience lung function deterioration if they continue to use their inhaled corticosteroids, whereas patients with COPD continue to lose lung function despite medication.

Opposite prescribing approaches

The first-line maintenance therapy for most patients with asthma is an inhaled corticosteroid; to prevent symptoms by minimising inflammation. Therapy should be titrated up or down, based on assessment of control. Short-acting bronchodilators, such as salbutamol, are required to treat symptoms as required and patients with good asthma control should rarely need to use their short-acting bronchodilator. For patients whose asthma is not well controlled on inhaled steroid therapy alone, adding a long-acting beta2-agonist may be considered.

For COPD, the approach is opposite. Bronchodilators are the first-line maintenance treatment for COPD and are fundamental in managing the disease symptoms. Inhaled cortisteroids are not the first-line therapy and are reserved for use in combination with a long-acting beta2-agonist in patients with severe to very severe COPD and who have frequent exacerbations.

Furthermore, in COPD therapy, inhaled cortisteroids therapy is not titrated on the basis of control but rather on exacerbation rates — it may be discontinued if there is no reduction in exacerbation rates. It is important, therefore, for pharmacists to establish what patients have been diagnosed with.

Other strategies

The non-drug component of management of asthma or COPD is where similarities lie. They involve lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation, diet (ie, good nutrition and weight loss or gain depending on circumstances) and exercise.

Treatment of co-existing conditions is crucial with both disorders, to differentiate symptoms and to ensure that appropriate treatment is being provided.

Patient education also plays a key role in optimising compliance and adherence with lifestyle adjustment and pharmacological therapy.

Summary

Ensuring appropriate prescribing is an area in which pharmacists can use their expertise and skills, but they should bear in mind that, unfortunately in clinical practice, the distinction between the two diseases, especially in the elderly, can be difficult.

In addition, patients with long standing or severe asthma — especially those who have inadequately had their underlying inflammation controlled — can present with chronic irreversible airflow obstruction with reduced fixed lung function secondary to remodelling within the airway. This makes the diagnosis of asthma sometimes challenging and these patients may be mislabelled as COPD patients. Furthermore, in 10 per cent of patients with COPD obstruction can be reversed by a bronchodilator and their airways behave like those in asthma patients, responding to inhaled corticosteroids.

It should also be remembered that COPD and asthma can occur together — those with asthma who smoke are likely to develop COPD.

Although asthma and COPD have many similarities, the focus of treatment for these two diseases and the outcomes that can be expected are different. Greater clarity on these differences will contribute to improved outcomes for these patients. The Panel summarises the key similarities and differences between the two diseases.

References

- Department of Health. An outcomes strategy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma in England. July 2011.

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Changes to the MUR service in 2011/12. Available at http://www.psnc.org.uk/pages/mur.html.

- British Thoracic Society. The burden of lung disease 2007. available at: http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/Library/BTS%20Publications/burdeon_of_lung_disease2007.pdf

- Colin-Thome D. Long term conditions: integrating community pharmacy. Executive summary. London. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Webstar Health 2006.

- Barnes P. Similarities and differences in inflammatory mechanisms of asthma and COPD. Breathe 2011;7(3):229–38.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax 2004;59(Suppl 1):1–232.

- British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline. 2011.

- Global initiative for asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2010. www.ginasthma.org.