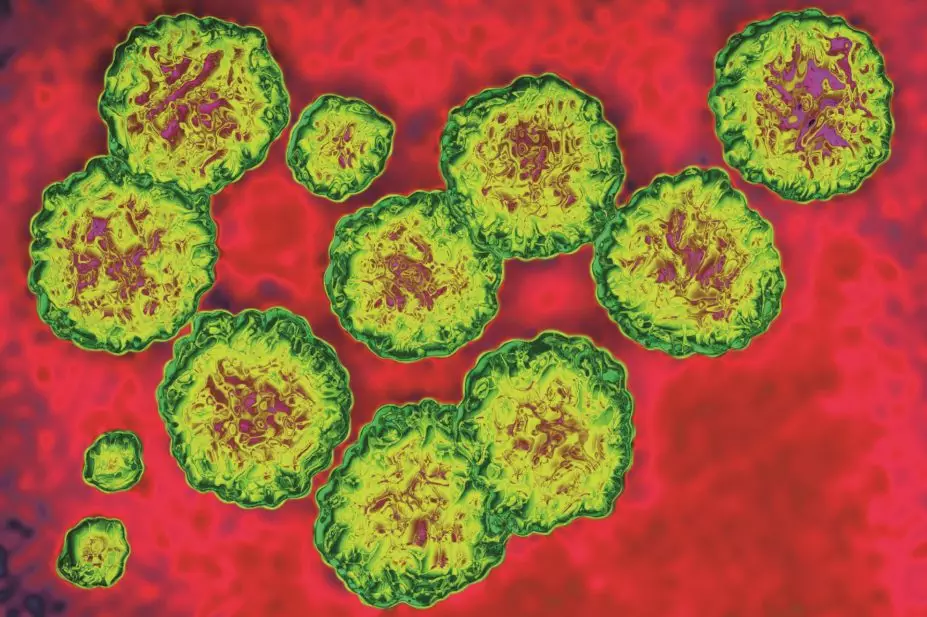

BSIP SA / Alamy

In this article you will learn:

- The lifecycle of hepatitis C virus and common routes of transmission

- The latest evidence on the new and developing hepatitis C treatments

- The mechanism of action of hepatitis C treatments

Hepatitis C is a global health problem, with an estimated 185 million people infected with the virus worldwide, with three to four million new infections each year. This is an estimated figure based on available prevalence data and supported by the World Health Organization.

There are six major genotypes of the virus, known as hepatitis C genotypes 1 to 6. Genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide, comprising more than 46% of all cases, of which one-third are in east Asia. Genotype 3 comprises 30% of all cases, while genotypes 2, 4 and 6 account for around 23% of cases. Genotype 5 accounts for the remaining 1%[1]

.

Recent years have seen an evolution in the treatment of hepatitis C infection, with new antivirals emerging at remarkable speed that promise cure rates never previously thought possible. This led to the licensing of several new hepatitis C treatments by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in late 2014, with further treatments in development and expected to be licensed in 2015 or 2016.

Lifecycle

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a blood-borne single-stranded RNA flavivirus. RNA viruses mutate to a greater extent than DNA viruses, resulting in difficulty for the body’s immune system to locate and destroy them. Steps in the life cycle of HCV include entry into the host cell (hepatocyte); uncoating of the viral genome; translation of viral proteins; and viral genome replication followed by assembly and release.

Non-structural proteins are essential for the viral life cycle processes and are the primary targets for the new antiviral medicines (see ‘Sites of action of new hepatitis C medicines’). In particular, the viral enzyme NS3/4 protease (important in viral protein production) and non-structural proteins NS5A and NS5B (which play a role in HCV replication) are targets.

Figure 1. Sites of action of new hepatitis C medicines[2]

| NS3/4 Protease Inhibitors | NS5A Inhibitors | NS5B Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Telaprevir | Daclatasvir | Sofosbuvir |

| Boceprevir | Ledipasvir | Dasabuvir |

| Simeprevir | Ombitasvir | |

| Asunaprevir | MK-8742 | |

| Paritaprevir | ||

| MK 5172 |

Transmission and prognosis

There are several routes for hepatitis C virus transmission.

People who inject drugs (PWID) are at risk, largely due to sharing unsterilized injecting paraphernalia. Around 50% of PWID in the UK are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus[3]

.

Vertical transmission from mother to child occurs in around 2% of mothers living with hepatitis C, although it can be as high as 20% in mothers co-infected with HIV. This risk increases in mothers who are viraemic (the infection is in the bloodstream) and are also infected with HIV[4]

.

Sexual exposure is a rare cause of transmission, and is estimated to account for less than 1% of cases. However, the risk increases in those who engage in sexual practices in which the risk of blood contact is increased[5]

.

Transfusion is now a rare cause of transmission following improved donor screening and viral inactivation of plasma products. Before these developments, patients who received infected blood products (e.g. haemophiliacs) were at the highest risk of contracting hepatitis C infection.

Occupational exposure is a possible risk (e.g. needle stick injuries), which can be minimised by safe working practices.

Other possible causes include tattooing, acupuncture, dental work and piercing. These risks can be minimised if good infection control practices are followed.

Hepatitis C is termed a silent killer as it causes slow but progressive liver damage. After initial infection with hepatitis C virus, around 75–85% of patients will fail to clear the virus and will become chronically infected[6]

. These patients will often be asymptomatic until they present with signs of end-stage liver disease (e.g. ascites, hepatic encephalopathy).

The remaining 15–25% of individuals go on to clear the infection and develop antibodies. It is important that patients are informed that spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C does not mean they are immune, and re-infection can occur. There is no vaccine to protect against hepatitis C infection.

It is estimated that around 30% of chronically infected patients will develop cirrhosis within 20 years of their original infection and 5% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Deaths in the UK as a result of end stage liver disease or HCC secondary to hepatitis C have quadrupled since 1996.

In England, only 3% of chronically infected hepatitis C patients are treated in England each year. Risk factors for accelerated progression of the disease include male gender, older age, obesity, infection with HIV, diabetes, and a significant alcohol history.

Anti-hepatitis C antibodies are usually present three to six months after infection. Diagnosis is made through a hepatitis C antibody test and a confirmatory hepatitis C RNA test to assess for active infection. Oral fluid testing is possible in some clinics but it is of lower sensitivity and specificity.

Treatment

The primary aim of hepatitis C antiviral treatment is for a patient to achieve viral eradication, or sustained viral response (SVR). The traditional time point for assessing if an SVR had been achieved was at 24 weeks post-treatment (SVR24), although 12-weeks post-treatment (SVR12) is now widely recognised as an appropriate assessment point.

Secondary aims of treatment include preventing transmission of the virus, preventing progression of liver damage, and improving patients’ quality of life.

Response rates to treatment are dictated by genotype, treatment history and patient specifics such as age, gender and other infections present. The stage of liver disease is also an important predictor of viral response. Traditionally, those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis achieve lower treatment response rates.

Peginterferon and ribavirin combination therapy is an established treatment for hepatitis C infection. Peginterferon is available as two forms: pegyalted interferon alfa-2a and alfa-2b. Both are administered once weekly by subcutaneous injection. The recommended starting dose of alfa-2a for the treatment of hepatitis C is 180mcg once weekly. The recommended dose for alfa-2b is 1.5mcg per kg per week. The dose of either peginterferon may be adjusted (lowered) depending on clinical factors, such as presence of thrombocytopenia or low mood.

Ribavirin is an oral tablet administered twice daily with food. The dose is dependent on the patient’s weight, but a range of 800–1200mg a day is common. The dose of ribavirin is often adjusted to account for the presence or absence of anaemia.

Treatment duration ranges from 24 to 72 weeks, with SVR24 rates of around 40–50% in patients with hepatitis C genotype 1, and 40–80% in patients with genotypes 2–6[7]

.

The peginterferon/ribavirin regimen has an extensive side effect profile, including cytopenia and mood disturbances. This limits its use in some patients, and it is estimated around 27% of patients prescribed a peginterferon stop treatment due to adverse effects[8]

. Side effects of ribavirin include dermatological effects (e.g. dermatitis, pruritis, urticaria and photosensitivity) and haematological abnormalities (e.g. anaemia).

Boceprevir and telaprevir were licensed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011. These medicines directly inhibit the replication stages of hepatitis C, and are licensed in Europe for use in genotype 1 patients in conjunction with peginterferon and ribavirin; telaprevir was discontinued in the United States in October 2014. The SVR24 rates in patients who have not previously been treated for hepatitis C are around 75% with telaprevir and 68% with boceprevir; SVR rates are lower in patients who have already been treated for hepatitis C or those with cirrhosis[9]

.

Boceprevir and telaprevir require a strict dose regimen, and are typically used in combination with a peginterferon. The licensed treatment duration is linked to a strict response guided protocol, where specific viral responses for both agents need to have been achieved for the regimen to continue. They require patients to take a large number of tablets (four 200mg tablets three times a day for boceprevir; three 375mg tablets every 12 hours, or two 375mg tablets every eight hours, for telaprevir), and have a treatment duration of 24–48 weeks.

Both boceprevir and telaprevir are substrates and inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 and, as a result, they interact heavily with a number of medicines, including tacrolimus and ciclopsporin, methadone, buprenorphine, statins, phenytoin and carbamazepine.

Boceprevir and telaprevir also have numerous side effects, including anaemia, pruritis, rashes, loss of appetite, thrombocytopenia, nausea and diarrhoea.

With the emergence of more effective and better tolerated antiviral agents, it is likely the use of boceprevir and telaprevir for genotype 1 hepatitis C will decrease significantly, as they are less clinically effective than newer agents.

Sofosbuvir is an NS5B nucleotide inhibitor approved by FDA in December 2013 and the EMA in January 2014. The NS5B RNA-dependent polymerase is responsible for replication of hepatitis C RNA.

Sofosbuvir is effective across all hepatitis genotypes, and is taken once daily as a 400mg single tablet. It has limited drug-drug interactions as it is not metabolised by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4. For patients with hepatitis C genotype 2, sofosbuvir is used with ribavirin for 12 weeks. Patients with other genotypes require a combination of sofosbuvir, peginterferon and ribavirin to enable a 12-week treatment duration; if a patient is intolerant to interferon and only sofosbuvir and ribavirin can be prescribed, then the treatment duration is extended to 24 weeks.

The clinical efficacy of sofosbuvir has been examined in a number of phase III trials, which included a proportion of difficult to treat populations, such as patients with cirrhosis. One single-group open-label study, which looked at patients prescribed sofosbuvir with interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks in 327 previously untreated patients with hepatitis C genotypes 1,4,5 and 6, found the sofosbuvir group had an overall SVR12 of 90% (80% in patients with cirrhosis)[10]

.

For genotype 2 and 3, the Phase III Fission study highlighted that genotype 2 did very well with sofosbuvir and ribavirin alone for 12 weeks, with an SVR of 97%, but genotype 3 did far less well, with an SVR of only 56%, which was less than the comparators of interferon and ribavirin[11]

. Further analysis for genotype 2 and 3 was completed in the Valence study, which extended treatment of sofosbvir and ribavirin to 24 weeks for genotype 3 patients. SVR12 rates increased to 85%.

Simeprevir, a NS3/4A protease inhibitor, was approved for use by the FDA in November 2013 and the EMA in March 2014. The licence allows use in combination with a peginterferon and ribavirin in genotype 1 and 4 patients. It is also licensed for use alongside sofosbuvir for those patients who are deemed unsuitable for interferon and require urgent treatment.

Treatment with simeprevir follows a response-guided protocol, similar to that used for boceprevir and telaprevir. Treatment durations range from 24–48 weeks depending on the patient’s genotype, disease stage and treatment history. The recommended dose of simeprevir is 150mg once daily for 12 weeks, followed by peginterferon and ribavirin for the remainder of treatment. Simeprevir is also licensed to be used in hepatitis C genotype 1 and 4 alongside sofosbuvir (with or without ribavirin); if this regimen is followed then the total duration of treatment is 12 weeks.

Simeprevir is better tolerated than the first generation protease inhibitors, with general malaise, fatigue, photosensitivity and rash as the most commonly reported side effects. It also requires patients to take fewer tablets and has a more simplified dosing regimen.

The Quest I and II studies examined the efficacy of simeprevir 150mg daily with peginterferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by peginterferon and ribavirin alone for the remainder of the course (24 or 48 weeks as guided by the viral response) in hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. The average SVR12 rate was 80%, with the lowest success rate in patients with genotype 1a who possessed the Q80K polymorphism (a naturally occurring polymorphism that occurs in certain strains of HCV)[12]

.

The estimated prevalence of hepatitis C genotype 1a with Q80K polymorphism in Europe is 19%[13]

. The EU license for simeprevir recommends testing for the Q80K polymorphism in patients with hepatitis C genotype 1a before starting treatment; if Q80K is detected, an alternative treatment should be considered.

The use of simeprevir and sofosbuvir as a combination therapy was evaluated in the COSMOS study, a randomised phase lla study conducted in two cohorts of patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Patients in both cohorts were randomly assigned to receive simeprevir 150mg once daily with sofosbuvir 400mg once daily (with or without ribavirin) for either 12 or 24 weeks. The cohorts included patients who had not previously received treatment or had not responded to treatment, and patients with and without cirrhosis.

SVR12 was achieved in 93–96% of patients treated for 12 weeks. The addition of ribavirin to the combination did not appear to contribute to higher SVR rates[14]

.

Daclatasvir, an NS5A inhibitor, was approved by the EMA in August 2014 for use in combination with other medicines for the treatment of hepatitis C genotypes 1, 2, 3 and 4. The recommended dose is 60mg once daily for 12 to 24 weeks. The dose should be reduced to 30mg when used with potent CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein inhibitors, and increased to 90mg once daily when used with CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein inducers.

One phase IIa study looked at treatment with daclatasvir 60mg once daily in combination with sofosbuvir 400mg once daily (with or without ribavirin) for 12 or 24 weeks in patients with hepatitis C genotypes 1, 2 and 3. The patients did not have cirrhosis, although some had previously received treatment for hepatitis C. SVR12 was achieved in 99% of patients with hepatitis C genotype 1, 96% with genotype 2, and 89% with genotype 3[15]

.

The evidence base available suggests that daclatasvir is well tolerated, with fatigue, headache and nausea reported as common side effects.

Harvoni, a fixed dose oral combination treatment combining sofosbuvir 400mg and ledipasvir 90mg, was authorised by the EMA in November 2014 for the treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1, 3 and 4, including those co-infected with HIV.

The recommended dose is one tablet once daily for 8, 12 or 24 weeks, depending on whether the patient has cirrhosis and if they have previously received treatment. Peginterferon is not used with this treatment, and ribavirin is only used in patients with cirrhosis.

Overall, the studies for Harvoni show a well tolerated regimen, with headache and fatigue being the most commonly reported side effects.

Viekirax, an oral combination of paritaprevir, an NS3/4A inhibitor, boosted with ritonavir co-formulated with ombitasvir, an NS5A inhibitor, was approved for use by the EMA in January 2015 for the treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1. This combination is co-administered with dasabuvir, an NS5B inhibitor, which was also approved by the EMA in January 2015.

Future treatments are likely to focus on new combinations of antivirals which use more potent protease inhibitors and do not require treatment with peginterferon.

Merck Sharpe and Dohme is currently developing a fixed dose, interferon-free combination for hepatitis C genotype 1, 4, 5 and 6. This combination, which is in phase II trials, includes MK5172, a NS3/4a protease inhibitor, and MK8743, an NS5A protease inhibitor.

References

[1] Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2014.

[2] Schinazi R, Halfon P, Marcellin P et al. HCV direct-acting antiviral agents: the best interferon-free combinations. Liver Int. 2014;34(Suppl1):69–78.

[3] London Joint Working Group on Substance Misuse and Hepatitis C. Practical Steps to Eliminating Hepatitis C: A Consensus for London. London:2014.

[4] Yeung LT, King SM & Roberts EA. Mother to infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2001;34(2):223.

[5] Terrault NA, Dodge JL, Murphy EL et al. Sexual Transmission of HCV among Monogamous Heterosexual Couples: the HCV Partners Study. Hepatology 2012.

[6] Zaltron S, Spinetti S, Biasi SL et al. Chronic HCV Infection: epidemiological and clinical relevance. BMC Infectious Dis 2012;12(Suppl 2).

[7] Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Rajender R et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus Ribavirin for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. N Engl J Med 2002:347(13):975–982.

[8] Gaeta GB, Precone DF, Felaco FM et al. Premature discontinuation of interferon plus ribavirin for adverse effects; a multicentre survey in “real world” patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1633–1639.

[9] Jacobson I, McHutchinson JG, Dushieko G et al. Telaprevir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. N Engl J Med 2011;354(25):2405–2416.

[10] Lawitz, E, Mangia A, Wyles D et al. Sofosbuvir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1878–1887.

[11] Zeuzem S, Dusheiko GM, Salupere R et al. Sofosbuvir and Ribavirin in HCV Genotypes 2 and 3. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1993–2001.

[12] Jacobson I, Dore GJ, Foster GR et al. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 2014;384(9941):403–413.

[13] Ghany, M, Gara N. QUEST for a cure for hepatitis C virus: the end is in sight. The Lancet 2014;384(9941):381–383.

[14] Lawitz E, Sulkowski MS, Ghalib R et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-naive patients: the COSMOS randomised study. The Lancet 2014;384(9956):1756–1765.

[15] Sulkowski MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370(3):211–221.