Source: Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- How to initiate low molecular weight heparins for venous thromboembolism

- Safety points to consider when using low molecular weight heparins

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) are used widely for the prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE comprises deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), a complication of DVT where some or all of the thrombus breaks away and lodges in the pulmonary arteries.

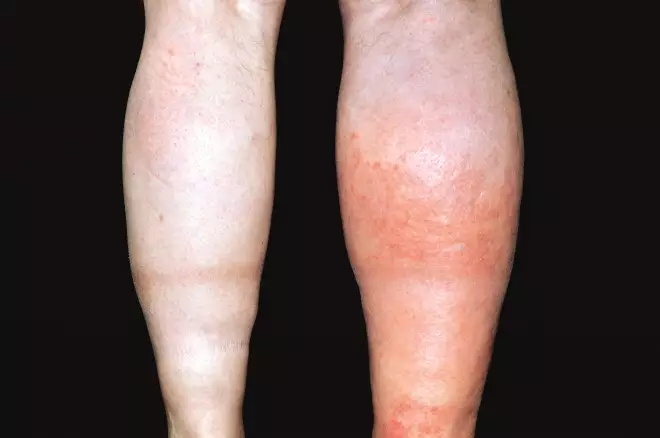

Source: Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) affecting the patient’s right leg, presenting as redness, pain and swelling

It is difficult to get a true picture of incidence of VTE. Currently, it is estimated that one person per 1,000 will be affected by a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) each year in the UK. The VTE impact assessment group in Europe (VITAE) performed epidemiological modelling of VTE in six European countries (including the UK), and estimated there were 465,715 cases of DVT, 295,982 cases of PE and 370,012 VTE-related deaths over the six countries each year[1]

. However, this study was before VTE risk assessment on admission for adult patients who are hospitalised became mandatory in the UK, and therefore these numbers are now likely to be considerably lower in the UK.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant. Medicinal heparin is usually derived from an animal source, usually mucosal tissue from pigs. LMWHs are manufactured by the enzymatic or chemical depolymerisation of unfractionated heparin (UFH)[2]

.

UFH binds to anti-thrombin, activating it and leading to inhibition of thrombin and factor Xa. Due to their shorter chain lengths, LMWHs exert their effect on factor Xa rather than inhibiting thrombin. Heparins and other anticoagulants do not dissolve blood clots; they prevent clots forming and prevent clots getting larger if already formed but it is the body itself that destroys the thrombus.

There are three LMWHs predominantly used in the UK: dalteparin, enoxaparin and tinzaparin. They all differ slightly in chain length, method of manufacture, renal excretion and licensed use, so they are not interchangeable on a unit for unit basis.

This article focuses on the initiation and monitoring of LMWH in the treatment of VTE. All the LMWHs are licensed in the UK for the treatment of VTE presenting as DVT, PE or both. The current treatment options for VTE are a LMWH used as monotherapy; a LMWH with warfarin until the international normalised ratio (INR) is in target range and then warfarin alone; or a LMWH for five days then dabigatran; rivaroxaban and apixaban are also licensed in the UK as monotherapy for the treatment of VTE. Specific patient groups presenting with VTE, such as those with active cancer or pregnant women, are usually managed solely on LMWH for VTE.

In pregnancy, LMWHs are recommended as the most appropriate treatment by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG)[3]

as there is evidence that they do not cross the placenta.

Heparins are porcine-derived products, and therefore some patients may not wish to be treated with them on religious or personal grounds. It is important to let patients know this so they can make an informed decision about their treatment.

Fondaparinux or one of the novel oral agents can be used as alternative treatments for patients who refuse to use heparin-based products, but this is dependent on indication, licence, renal function and concomitant illnesses and medications.

Starting treatment

Patients who start LMWH for the treatment of VTE should have baseline full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&Es), liver function tests (LFTs), and a clotting screen.

If the patient has an increased risk of bleeding, such as a raised prothrombin time, international normalised ratio (INR) or activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), then the risk of anticoagulation compared with the benefit needs to be assessed. A consultant haematologist may need to be involved and, if it is decided that anticoagulation should not be withheld, it may be safer to commence with a more quickly reversible agent such as unfractionated heparin while investigating the cause of the clotting disorder.

In January 2015 NHS England issued a safety alert highlighting when low molecular weight heparins may be contraindicated. Examples included patients with: active bleeding (in whom all anticoagulants are contraindicated); acquired bleeding disorder (such as acute liver failure); concurrent use of anticoagulants known to increase risk of bleeding; concurrent use of antiplatelets and other interacting medicines; or patients who had received a lumbar puncture, epidural or spinal anaesthesia within the previous four hours, or one was expected within the next 12 hours[4]

.

The dose of LMWH given is based on the patient’s body weight and renal function (see ‘Doses of commonly-used low molecular weight heparins’). For obese patients individual summary of product characteristics (SPCs) and local guidance should be consulted.

Doses of commonly-used low molecular weight heparins for VTE

Dalteparin[5]

| DALTEPARIN | |

|---|---|

| Patient weight | Dose |

46–56kg | 10,000 IU |

57–68kg | 12,500 IU |

69–82kg | 15,000 IU |

83kg and over | 18,000 IU |

Enoxaparin[6]

| ENOXAPARIN | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dosage chart for 1.5mg/kg subcutaneous treatment of DVT, PE or both | ||

| 100mg/ml solution for injection Clexane syringes | ||

| Patient weight | Syringe label | Dose |

| 40kg | 60mg / 0.6ml | 60mg once daily (0.6ml) |

| 45kg | 80mg / 0.8ml | 67.5mg once daily (0.675ml) |

| 50kg | 80mg / 0.8ml | 75mg once daily (0.75ml) |

| 55kg | 100mg / 1ml | 82.5mg once daily (0.825ml) |

| 60kg | 100mg / 1ml | 90mg once daily (0.9ml) |

| 65kg | 100mg / 1ml | 97.5mg once daily (0.975ml) |

| 150mg/ml solution for injection Clexane Forte syringes | ||

| Patient weight | Syringe label | Dose (mg) |

| 70kg | 120mg / 0.8ml | 105mg once daily (0.7ml) |

| 75kg | 120mg / 0.8ml | 112.5mg once daily (0.76ml) |

| 80kg | 120mg / 0.8ml | 120mg once daily (0.8ml) |

| 85kg | 150mg / 1ml | 127.5mg once daily (0.86ml) |

| 90kg | 150mg / 1ml | 135mg once daily (0.9ml) |

| 95kg | 150mg / 1ml | 142.5mg once daily (0.96ml) |

| 100kg | 150mg / 1ml | 150mg once daily (1ml) |

Tinzaparin[7]

| TINZAPARIN |

|---|

| 175 units/kg |

It is therefore extremely important that the patient is weighed before starting treatment. If the patient is too unwell to be weighed, it is reasonable to estimate for the first dose but an accurate weight should be obtained as soon as possible.

Many hospital laboratories will report estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as a measure of renal function. However, the main clinical trials for LMWHs used creatinine clearance (determined by the Cockcroft-Gault equation) as the measure of renal function, and therefore this should be calculated, especially for patients with raised creatinine or low body weight. If anticoagulation is urgent and renal function cannot be calculated accurately, then the first dose should be given and subsequent doses adjusted as required.

Cockcroft-Gault equation

Estimated creatinine clearance = (140 – age) x mass (kg) x 1.23 (men) or 1.04 (women)

serum creatinine (µmol/l)

All LMWHs are given by subcutaneous injection, usually into the subcutaneous layer on the abdomen. Other sites, such as the arms, legs and back, can be used if the abdomen cannot be used or starts to get bruised with long-term use[8]

. Patients or their carers should be taught to self-inject whenever possible. LMWHs are only given once a day in the majority of cases and the dose should be given as near as possible to the same time each day.

Twice-daily injections may be recommended in some patients, for example during pregnancy or in patients with recurrent events occurring while on appropriate treatment[9]

.

Most patients do not require a long course of LMWH unless they cannot use another form of anticoagulation; they are pregnant, when they will be on treatment for the duration of pregnancy and at least six weeks after childbirth (but warfarin can be initiated from day four post-delivery so women may be able to stop LMWH once the INR is in range); or have active cancer, when the usual treatment duration is at least six months.

In short courses of LMWH, for example five to ten days (i.e. for patients being initiated on warfarin), most patients require no further monitoring of their LMWH after baseline tests. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is less common with LMWH than with unfractionated heparin but can still occur. The British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) guideline on the diagnosis and management of HIT states that all patients require a baseline platelet count[10]

.

No further monitoring is required unless the patient is post-operative and has received heparin in the past 100 days, when a platelet count should be performed 24 hours after starting treatment; if the patient has been on cardiopulmonary bypass, platelet counts should be monitored every two to three days from day 4 until day 14.

However, for patients with poor renal function (a creatinine clearance of less than 30ml/minute) or who are pregnant or very obese (for example patients on tinzaparin who weigh more than 165kg), or for children, it may be necessary to repeat weight and renal function and possibly monitor anti-factor Xa levels. Anti-factor Xa levels should be taken around four hours post-dose, with the usual range quoted for patients on a treatment dose being 0.5–1.0 international units/ml.

Sharps bins should always be issued when patients are discharged with LMWH syringes, and should be returned once full or no longer required.

The most common side effects tend to be haemorrhage and injection site reactions. Patients with signs or symptoms of bleeding need urgent review. Patients with mild injection site reactions can be advised to alter the site and have their injection technique checked.

All heparins can cause hyperkalaemia in at-risk patients, such as patients with diabetes or renal impairment, and these patients should have their potassium levels monitored regularly.

Other possible side effects include allergic reactions and increases in markers of liver function, especially transaminases.

Stopping treatment

LMWHs can be stopped abruptly if the patient reaches the end of their prescribed course and is not transferring to an oral anticoagulant.

If the patient is being initiated on warfarin, this can be started at the same time as the LMWH and the LMWH should be continued until the patient’s INR is more than 2 on two consecutive tests (usually a day apart). In these patients, the LMWH is usually continued for at least five days (six for tinzaparin).

If the patient is transferring to a different injectable anticoagulant, such as fondaparinux, or one of the novel oral agents (rivaroxaban, dabigatran or apixaban), the LMWH should be stopped abruptly, and the new treatment started at the time the next LMWH dose was due.

Katherine Stirling is a consultant pharmacist in anticoagulation and thrombosis for Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

References

[1] Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA et al . Venous thromboembolism in Europe. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:756–764.

[2] Garcia DA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI et al. Parenteral anticoagulants: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.Chest 2012;141(2_suppl):e24S–e43S.

[3] Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists. Thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium, the acute management of (Green-top Guideline No. 37b). London:RCOG 2009.

[4] NHS England. Patient Safety Alert - Harm from using low molecular weight heparins when contraindicated. Leeds:NHS England 2015.

[5] Fragmin (Dalteparin) SPC accessed 30/01/2015

[6] Clexane (Enoxaparin) SPC accessed 30/01/2015

[7] Innohep (Tinzaparin) SPC accessed 30/01/2015

[8] Dougherty L & Lister S. Royal Marsden Hospital Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. London: Wiley-Blackwell 2011.

[9] Radhakrishna G & Berridge D. Cancer-related venous thromboembolic disease: current management and areas of uncertainty. Phlebology 2012;272:53–60.

[10] Watson H, Davidson S & Keeling D. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of heparin induced thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol 2012;159:528–540.