Shutterstock.com

A 2017 survey conducted by The

Pharmaceutical Journal found that 30% of pharmacists encounter a foot condition more than once per week[1]

. Pain on the under (plantar) surface of the heel is common in the adult and paediatric population; however, there could be up to 50 causes for this[2]

.

This article outlines the most common cause of plantar heel pain (PHP) in adults, plantar fasciopathy (PF), how to differentiate PF from other causes of PHP, the advice that pharmacists and healthcare professionals can give to patients and when to refer.

Prevalence of plantar fasciopathy

Around 10% of the adult population will experience PHP and in 80% of these cases, the cause is PF[3]

. People aged 40–60 years are most commonly affected, with some evidence suggesting that women experience pain for longer when the condition becomes chronic (i.e. continues beyond three months)[4]

. PF is more commonly known as plantar fasciitis, but fasciopathy reflects the degenerative rather than inflammatory nature of the condition[5]

.

Diagnosis

The pain experienced by people with PF is associated with a thickening of the plantar fascia where it originates from the calcaneum ([heel bone]; see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Plantar fasciopathy

Source: Andreas Ehrhard / Alamy Stock Photo. Blower N. Innovations in the management of heel pain. 2018[2]

Arrow on x-ray shows area of plantar fascial thickening. Thickening of >4mm correlates with heel pain in plantar fasciopathy.

This area is a fibrocartilagenous enthesis. Although the reason for the thickening is debated, risk factors include mechanical tissue stress, load being transferred from the achilles tendon via fascial ‘tightness’, obesity (as opposed to increased body mass index [BMI], e.g. in the athletic population), ageing and occupational standing[6]

. The relationship between PF and the mechanics of the arches of the feet is, however, equivocal. Therefore, the use of foot orthoses, such as arch supports, is debated in this condition[7],[8]

.

Signs and symptoms

There are signs and symptoms that can be established during basic history taking that will help to differentiate between PF and the other causes of PHP (see Table 1 and Table 2). Careful questioning by pharmacists alongside examination of a patient presenting with foot pain can help to elucidate the cause.

In the community pharmacy setting, the person undertaking this assessment should be confident in their knowledge of how to palpate the foot (see Figure 2) to establish the area of pain and how to take a patient history. Local policies and training will need to determine who undertakes this assessment.

Assessing the patient

When a patient presents with PHP (see Box 1), pharmacists should ensure an appropriate history is taken and relevant observations and examinations are made. Pertinent questions include:

- Where is the pain (ask the patient to point to it with a bare foot)?

- When did the pain start and how?

- How old is the patient?

- Are they overweight?

- When is the pain at its worst?

- Is there pain at night?

- What is the pain like?

- Is it sharp? Is it achy? Is it burning?

- Is there any other significant medical history (e.g. infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, or inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis)?

- Is the area where the pain is located swollen or bruised?

Box 1: Typical plantar fasciopathy patient profile

- Pain on the plantar/plantar-medial surface of the heel;

- Adult (heel pain in children is not ordinarily plantar fasciopathy);

- Non-traumatic cause, gradual onset of pain;

- May be overweight or experience occupational standing;

- Symptoms are worse on getting out of bed or standing after sitting for a long period;

- Pain will be described as sharp, achy or burning, but not usually numb;

- Not experiencing nocturnal pain and pain improves when not weight-bearing;

- Walking a few steps will improve the pain and then the pain will return or be irritated by increased load-bearing;

- No associated history of rheumatological conditions (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis);

- No current spinally referred pain (e.g. sciatica).

Identifying the location of the pain

It is important to be sure about the location of the pain. Not all pain under the foot is caused by the plantar fascia and not all PHP is caused by PF. The pain in PF is located at the point shown in Figure 2 or slightly further back (more proximal) on the plantar surface of the heel.

Figure 2: Palpating the area of pain caused by plantar fasciopathy

Pain associated with plantar fasciopathy is located at the point indicated (by the forefinger in the image) or slightly further back (more proximal) on the plantar surface of the heel

To be precise about the location of pain, pharmacy professionals should follow these steps:

- Ask the patient to remove their shoes and socks in order to see the features of the foot;

- Observe the foot for bruising or obvious injury (this will not be present in PF);

- Ask the patient to take one finger and point exactly to where the most intense pain is;

- If the pain is in the location in Figure 2 and their symptoms fit PF (as in Box 1 and Table 1), then it is likely to be PF;

- If the patient is uncertain as to the location of the pain in the heel, there is the option to palpate (physically press) the area in Figure 2, which should reproduce their symptoms;

- If the pain is elsewhere in the foot it may be another cause of PHP or foot pain, as explained in Table 2.

Physical examination should only be undertaken by trained pharmacists who should be appropriately insured to do so. If it is not possible for a pharmacist to palpate the foot, the patient should be asked to press the foot to identify the area of pain instead.

Differential diagnosis

If the pain is not in the area of the heel shown in Figure 2 and the patient does not fit the profile (see Box 1), they may have another cause of PHP. Table 1 describes the signs or symptoms that can help determine the cause of the patient’s heel pain. As an example, PF is never traumatic and is not usually seen in children. ×, ×

| Sign or symptom | Plantar fasciopathy | Other causes of plantar heel pain |

|---|---|---|

| Adult | ✔ | ✔ |

| Paediatric | × | ✔ |

| Pain at rest, nocturnal | × | ✔ |

| Pain on initiation of activity (start-up pain) | ✔ | × |

| Traumatic cause | × | ✔ |

| Non-traumatic cause | ✔ | ✔ |

| Obvious inflammation, bruising | × | ✔ |

| Sharp, achy pain | ✔ | ✔ |

| Numbness, tingling, burning pain | ✔ | ✔ |

However, there are numerous other potential causes of heel pain (see Table 2).

| Structure/system | Condition/presentation |

|---|---|

| *Please note that this table is not exhaustive | |

| Skeletal | Calcaneal fracture, calcaneal apophysitis (Sever’s disease) — this is the main cause of heel pain in children |

| Soft tissue | Heel pad bruising, plantar fascial rupture (traumatic or post-steroid injection), pain in the arch from tendons (e.g. tibialis posterior tendinopathy) |

| Infection/foreign bodies | Calcaneal, soft tissue, foreign body |

| Systemic disease | Rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, gout, psoriatic arthritis |

| Metabolic | Osteoporosis (also in high level athletes), Paget’s disease, hyperparathyroidism |

| Benign neoplasms | Lipoma, bone cysts, osteoid osteoma, giant cell tumour |

| Malignant neoplasms | Metastases, sarcoma (e.g. Ewing’s sarcoma in paediatrics) |

| Neurological | Local nerve affectation (e.g. first branch of lateral plantar nerve), tarsal tunnel syndrome, spinal referral (lumbo-sacral), chronic regional pain syndrome |

Treatment

If, after taking a history, the pharmacist is confident the patient has PF, staged treatment is recommended. Table 3 outlines these stages, as well as the related advice and responsible clinician[9]

.

The role of the pharmacy team focuses mainly on providing the initial advice outlined in Table 3. Any healthcare professional seeing a patient with PF who has not been advised or treated previously should start with these measures.

| Duration of pain | Treatment advice | Responsible clinician |

|---|---|---|

| Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: plantar fasciitis[9] . | ||

| 0–6 weeks (or no previous advice or treatment) | Initial advice for all patients: stretching exercises (see Figure 3); rest from irritating activities such as long periods of standing; supportive, cushioned shoes (avoid barefoot); weight loss; cushioned/gel insoles (see Box 2); analgesia | Any |

| 6 weeks–3 months (if above advice fails or symptoms severe) | Guided corticosteroid injection; podiatry treatment; physiotherapy treatment | GP, consultant, extended scope allied healthcare professional, Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC)-registered podiatrist or physiotherapist |

| 3–6 months | Extra-corporeal shockwave therapy | Consultant or HCPC-registered podiatrist or physiotherapist |

| 6–12 months | Platelet-rich plasma infiltration, surgery | Consultant |

The evidence base does not support the use of foot orthoses for the treatment of PF. However, it is recognised that anecdotally they can be of benefit and that this is not reflected in the research, possibly owing to inappropriate study design. As such, advising patients that arch supports will improve the condition may be misleading[8]

; however, general cushioning from shoes and insoles will help (see Box 2).

Box 2: Pharmacy insoles versus podiatrist-prescribed foot orthoses

- Insoles in plantar fasciopathy (PF) should be cushioned at the heel (e.g. gel heel pads);

- Any insoles should be correctly fitted (to shoe size and foot) and pharmacists should advise patients that their shoe choice may have to change to accommodate the insole (e.g. lace-up shoes instead of flat slip-on shoes);

- If cushioning does not help relieve some of the pain experienced, pharmacists should advise patients to consult a podiatrist, who, if appropriate, may advise a prescribed foot orthotic based on the patient’s mechanics and pain location;

- There is a lack of evidence to support the use of foot orthoses in PF, so care must be taken not to make any false claims about their efficacy and action[8]

.

Pharmacological management

Analgesia should be advised on the basis of the severity of the pain being experienced by the patient, in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance[10]

. Some symptoms may be helped by over-the-counter analgesics[10]

. However, analgesia alone will not be enough to treat the condition effectively and should not be considered without the additional advice in Table 3.

Lifestyle management

Rest alone will not be enough to alleviate all the pain in PF but avoiding deliberately aggravating activities (e.g. high-impact activities such as running, standing for long periods and walking barefoot) will help to reduce the aggravating factors[9]

. Wearing good footwear (see Box 3) is likely to improve PF symptoms but, again, there are no controlled trials to support this. However, as the pain from PF emanates from the thickening of the plantar fascia under the heel, cushioning and protecting this area can help relieve symptoms.

Box 3: Advice on footwear

Shoes can be a cause of foot pain. They can be too high or too low at the heel, have little or no support (e.g. slip-ons such as ballet shoes) and can be the wrong length, width fitting or shape for the patient’s foot. The internal stitching or tacks may also rub against the foot.

In general, shoes should have an upper made from a natural material that will stretch and allow evaporation of moisture, have an adequate width, depth and shape to the toe box to prevent rubbing, and have a heel height of less than 4cm to prevent forefoot pressure and aid normal walking mechanics.

Patients should be advised to wear the right shoe for the activity they are doing. Women do not have to avoid wearing high heels or ballet shoes to prevent foot pain, but it is best not to wear these if walking for longer distances or standing for sustained periods. Some occupations, however, make this more difficult to achieve.

A good pair of shoes to walk longer distances in should have a synthetic sole to help support and cushion the foot (especially on harder surfaces) and a fastening so that the shoe moves with the foot, rather than the foot moving around in the shoe.

In plantar fasciopathy, one of the most important features of a shoe that will help relieve symptoms is cushioning inside the shoe and a thicker sole, ideally with a fastening so the foot can work more efficiently.

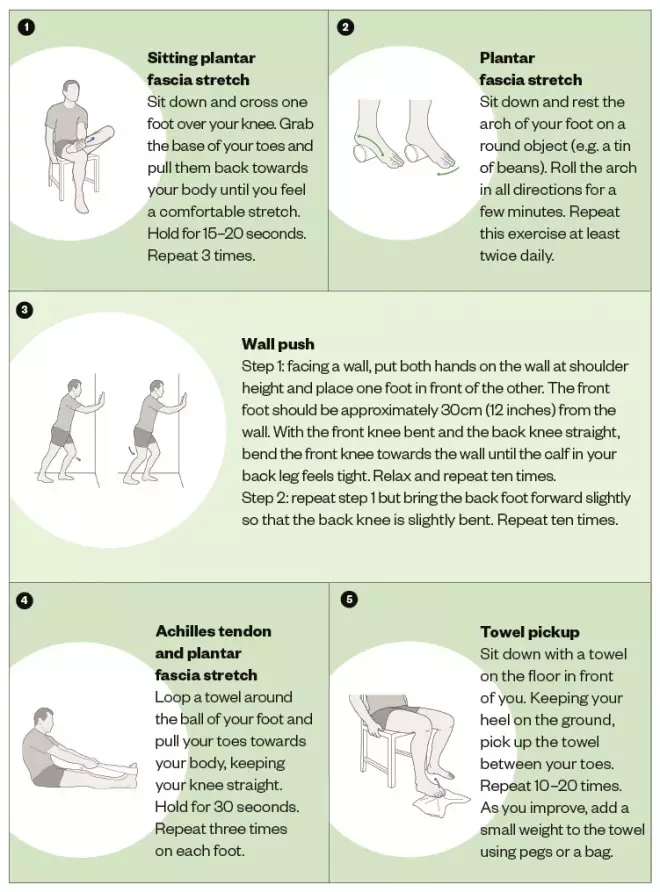

Stretching

It is known that stretching is effective at relieving pain in PF but the method of stretching is poorly described. There is some consensus that stretching the plantar fascia is more effective than stretching the calves alone; therefore, the stretches described in Figure 3 are recommended[11]

.

- The patient can stretch the foot and ankle themselves or someone can help them;

- This can also be done with a bare foot, sitting in a chair, with the knee straight and using a belt or a dressing gown cord to pull the toes and ankle up;

- Using a tennis ball or a small foam roller, the plantar fascia can be stretched by rolling into the arch of the foot. The number of repetitions for these exercises is not agreed on in the literature, but it is advised that they are done daily for at least five minutes each in order for them to be effective.

Figure 3: Exercises to manage foot pain

Source: Courtesy of Versus Arthritis

The foot can be affected by many different conditions. Two causes of foot pain are plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinitis. Try the exercises suggested here to help ease pain and prevent future injuries. Your pain should ease within 2 weeks and you should recover over approximately a 4–6-week period.

Weight loss

Symptoms may be improved by weight loss, achieved through diet and low-impact physical activity. There is a specific correlation between increased BMI in the non-athletic population and PF. Patients should be advised of the link and signposted accordingly[12]

.

Referral

Patients seeking NHS treatment should be referred to their GP for onward referral. However, patients who are seeking private treatment should ensure the clinician recommended is appropriately qualified. Podiatrists working in private practice will usually take self-referrals from patients. However, a referral from a healthcare professional can be useful in identifying medical history and medicines (which patients sometimes forget and often do not realise are important in diagnosing their condition). Podiatrists/chiropodists and physiotherapists should be registered with the Health and Care Professions Council[13]

, which regulates 16 health and care professions.

Referrals to NHS podiatrists vary. Some NHS community trusts accept self-referral, while others have tight restrictions on who can be referred.

Supported by RB

RB provided financial support in the production of this content.

The author was not paid to write this article and The Pharmaceutical Journal retained full editorial control at all times.

References

[1] Robinson J. The Pharmaceutical Journal launches foot health partnership with RB. Pharm J 2017;299(7904):S2–S3. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20203112

[2] Blower N. Innovations in the management of heel pain. [Presentation] Primary Care and Public Health Conference. 17 May 2018.

[3] Neufeld SK & Cerrato R. Plantar fasciitis: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2008;16(6):338–346. PMID: 18524985

[4] Hansen L, Krogh TP, Ellingsen T et al. Long-term prognosis of plantar fasciitis. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6(3):2325967118757983. doi: 10.1177/2325967118757983

[5] Radwan YA, Mansour AMR & Badawy WS. Resistant plantar fasciopathy: shock wave versus endoscopic plantar fascial release. Int Orthop 2012;36(10):2147–2156. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1608-4

[6] Johal KS & Milner SA. Plantar fasciitis and the calcaneal spur: fact or fiction? Foot Ankle Surg 2012;18(1):39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2011.03.003

[7] Wearing SC, Smeathers JE, Urry SR et al. The pathomechanics of plantar fasciitis. Sports Med 2006;36(7):585–611. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636070-00004

[8] Whittaker GA, Munteanu SE, Menz HB et al. Foot orthoses for plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2018;52(5):322–328. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097355

[9] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: plantar fasciitis. June 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/plantar-fasciitis#!scenario (accessed November 2018)

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia-mild-to-moderate-pain (accessed November 2018)

[11] Arthritis Research UK. Information and exercise sheet (H02): plantar fasciitis. 2004. Available at: https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/health-professionals-and-students/information-for-your-patients/exercise-sheets-and-videos.aspx (accessed November 2018)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: obesity. January 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/obesity#!scenario (accessed November 2018)

[13] Health and Care Professions Council. Check the register. Available at: http://www.hcpc-uk.org/check-the-register/ (accessed November 2018)