This content was published in 2007. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Raynaud’s phenomenon was first described in 1862 by Maurice Raynaud. It is characterised by episodic spasming of the small blood vessels of the extremities. The fingers are most commonly affected, but vasospasm can also occur in the toes, nose, ears and, occasionally, the tongue and lips.

The vasospasm cuts off the blood supply in the affected fingers, resulting in whitening and pain. This is sometimes followed by cyanosis (the affected fingers turn blue) due to pooling of deoxygenated blood. An episode ends with vasodilation and reperfusion and the finger(s) turns red. This white-blue-red colour change is characteristic of the reversible local ischaemia but is not observed in all patients.

The ischaemic pain during an attack can be considerable and has been compared to plunging your hands into a bucket of icy water and holding them there. As blood flow returns, in the final stage, there is often tingling, throbbing, numbness and further pain. During an attack, hand function is limited. The vasospasm is thought to be an exaggerated response to cold or some other form of stress. Attacks are usually mild and last for a few minutes, but some people experience multiple and prolonged episodes, lasting hours.

When Raynaud’s symptoms first present, one or two fingers may be affected but, with time, all fingers tend to become involved. Episodes tend to be symmetrical, affecting each hand equally. Complications of the phenomenon include ulceration, scarring and pitting, and gangrene, but these are rare.

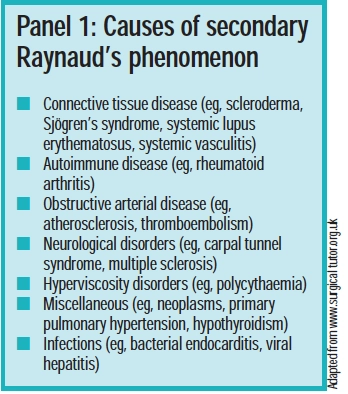

In over 90 per cent of cases there is no identifiable cause for the condition and this is termed primary Raynaud’s phenomenon (also sometimes referred to as Raynaud’s disease). If, however, the condition is due to an underlying disease (see Panel 1 for examples), it is described as secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.

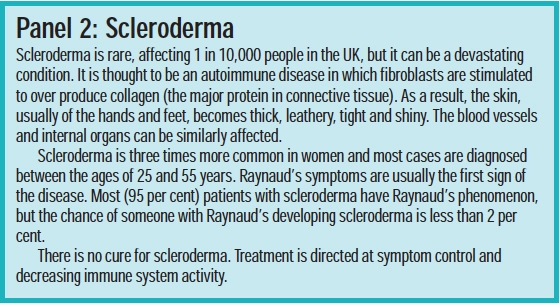

It has been estimated that scleroderma accounts for 65 per cent of secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon (see Panel 2).

Raynaud’s symptoms can also be caused by exposure to vibration, known as “vibration white finger” (eg, in occupations that involve using pneumatic drills or chainsaws), prolonged cold (eg, in meat packers), or chemicals (eg, in the polyvinylchloride industry).

Identify knowledge gaps

- What can cause Raynaud’s symptoms?

- What practical advice can be offered someone with Raynaud’s phenomenon?

- What drugs are used to manage Raynaud’s phenomenon?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “common disease states” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Raynaud’s phenomenon has been linked to some autoimmune diseases. Up to 5 per cent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have Raynaud’s symptoms as do up to 30 per cent of people with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Drugs that can cause (or exacerbate) Raynaud’s phenomenon include some angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, enalapril and lisinopril) beta-blockers, some cytotoxics (eg, bleomycin, cisplatin), bromocriptine, clonidine, ergotamines, lisuride, methysergide, pergolide and sumatriptan. Other drugs that have been linked with Raynaud’s phenomenon include amphetamines, interferon-alpha, lithium and combined oral contraceptives.

The overall incidence of Raynaud’s phenomenon is 3–20 per cent of the adult population worldwide, with more women (over 90 per cent) affected than men. In the UK, around 10 per cent of women experience Raynaud’s phenomenon to some degree. Surveys of Scandinavian women aged 18 to 60 years suggest that higher numbers are affected — up to 22 per cent.

Typical age of onset is usually quoted as being in the teenage years or early twenties. However, a recent Bandolier look at 10 studies including 639 patients found the average age of onset of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon was 34 years.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon in women under the age of 30 years, following a detailed medical history, is usually straightforward. However, if symptoms present in someone over the age of 30 (secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon tends to present later in life), especially in the presence of other factors, further investigations may be warranted to distinguish between primary and secondary disease. Other factors are:2

- Abrupt onset with rapid progression

- Unilateral or asymmetrical vasospasm

- Symptoms of arthralgia or arthritis

- Skin rashes or photosensitivity

- Dry eyes or mouth

- Muscle weakness or pain

- Swallowing difficulties

- Breathlessness

- Mouth ulcers

Investigations that can be undertaken to screen for underlying disease include:

- Nailfold capillary microscopy to look for any capillary abnormalities

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) tomeasure the degree of inflammation

- Antinuclear antibody test (ANA) to screen for the presence of antibodies found in connective tissue or other autoimmune disorders

Patients with primary Raynaud’s experience periodic vasospastic attacks precipitated by cold or stress. Their nailfold capillaries are normal, as are their ESR and ANA results. Complications (eg, tissue death) are less likely in people with primary disease.

Since it is unlikely for symptoms to be evident at the point of consultation, it can be useful for patients to ask someone to photograph their hands (or other affected area) during an attack.

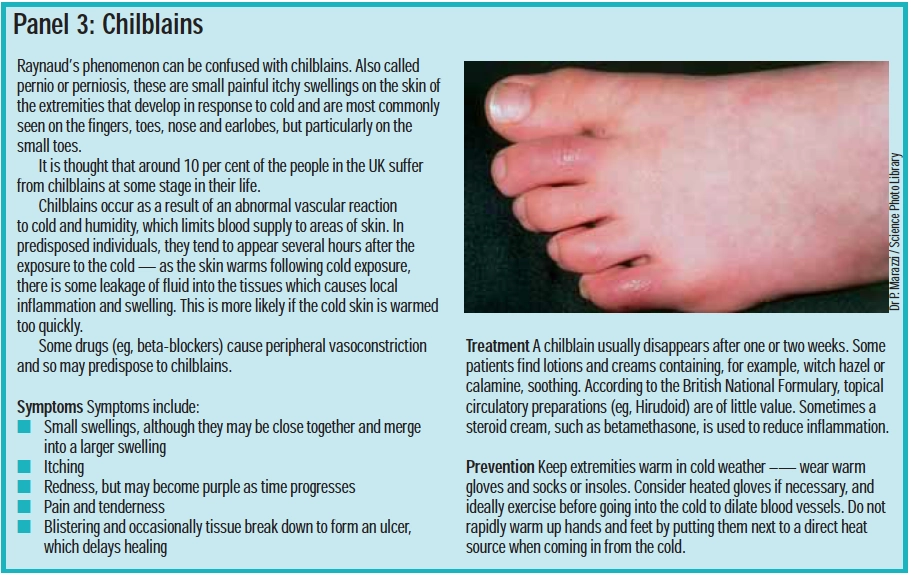

Other conditions, such as chilblains (see Panel 3) can be confused with Raynaud’s phenomenon. People with continued episodes of suspected chilblains should be referred to their GP.

Management

Disease severity is assessed by enquiring about the frequency of episodes, the severity of ischaemia, the sites affected and impact on daily life. For most patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, symptoms are mild and do not interfere with day-to-day living. And for two thirds of patients, symptoms are likely to resolve spontaneously.

A study following 1,358 patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon over seven years found that in 64 per cent of people, symptoms had remitted by the end of the study.3 However, 10 per cent of patients will develop some form of connective tissue disease within about 10 years of the onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon.

For all patients with Raynaud’s, non-pharmacological measures should be recommended and are sufficient to manage most cases. These are listed in Panel 4.

Drug treatment

When non-pharmacological strategies are insufficient and symptoms interfere with daily life, drug treatment should be considered. Treatment is usually more successful in people with primary disease. Several drugs have been investigated for use in Raynaud’s phenomenon, but interpretation of studies is difficult because of the different criteria used.

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers are commonly the first choice in Raynaud’s when drug treatment is indicated, although there is limited evidence of their efficacy.1 One meta-analysis found that calcium channel blockers reduced the frequency of ischaemic attacks by an average of 2.8–5.0 per week and reduced severity by 33 per cent.4

Nifedipine is the most commonly used and has the most evidence of benefit. It is the only calcium channel blocker licensed to treat Raynaud’s phenomenon. It relaxes vascular smooth muscle, causing peripheral vasodilation. A starting dose of 5mg tds is recommended, which is adjusted, according to response to up to 20mg tds. Common side effects are flushing and headache (these are most significant in the early days of dosing and often decrease with continued treatment) and ankle oedema. The antihypertensive properties of nifedipine can mean that it is not suitable for patients with low blood pressure. Nifidipine should also not be used within a month of a heart attack, or in people with heart failure. Since sufferers are commonly young women, nifedipine’s contraindication in pregnancy and breast-feeding should be borne in mind.

Patients with severe symptoms take nifedipine regularly but others only take it during the winter months when their symptoms are at their worst. The modified release nifedipine preparations are not licensed for Raynaud’s phenomenon, but they may be better tolerated.

Other dihydropyridine calcium-channelblockers (amlodipine, felodipine, israpidine) have shown some benefits in small studies. Verapamil and diltiazem are not recommended because their main site of action is on myocardial tissue and they have a lesser effect on the peripheral vasculature.

Licensed drugs

Other peripheral vasodilators such as naftidrofuryl and inositol nicotinate are sometimes used but are of uncertain value. They may have application in those who are intolerant to calcium antagonists. Pentoxifylline, prazosin and moxisylyte are also licensed for use in Raynaud’s, but are not established as being effective.

Unlicensed drugs

ACE inhibitors (despite the fact that some cause Raynaud’s symptoms) and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists may provide some small benefits in Raynaud’s phenomenon. There is no evidence to suggest that they are more effective than the calcium channel blockers. In trials investigating its short-term use, losartan has shown benefits in Raynaud’s symptoms in patients with scleroderma. Long-term use is yet to be investigated.

The effect of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine, has been investigated. Serotonin causes vasoconstriction so by reducing serotonin levels, some vasodilation is achieved. Results to date have been promising but more evidence is needed.

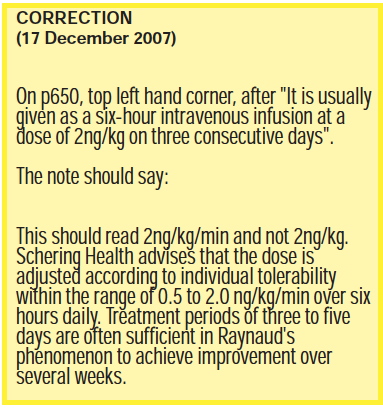

Prostaglandin E1 and prostacyclin are potent vasodilators and inhibit platelet aggregation. The prostacyclin analogue iloprost (with a half-life 10 times that of prostacyclin) has been used on a named-patient basis to manage severe Raynaud’s symptoms, particularly in patients with scleroderma. It has been shown to reduce both frequency and severity of attacks4 and been used in the treatment of fingertip ulcers associated with Raynaud’s symptoms. It is usually given as a six-hour intravenous infusion at a dose of 2ng/kg on three consecutive days. Benefits can last for six weeks or more.5

The micro- and macrovascular dilating properties of sildenafil have shown promising results in accelerating digital ulcer healing rates in scleroderma patients with Raynaud’s symptoms. In a trial, 50mg bd of sildenafil, given for four weeks, gave clear improvement of symptoms.6

Food supplements

A number of food supple-ments have been proposed as being beneficialin Raynaud’s phenomenon, including anti-oxidants and fish oils. The World Health Organization has recommended the use of Ginkgo biloba in the treatment of Raynaud’s. Ginkgo biloba, 120mg tds, was effective in reducing the number of attacks of Raynaud’s compared with placebo. The supplement was well tolerated by patients.7

Surgery

For patients with severe symptoms and who do not respond to other treatments, a sympathectomy — cutting the nerves that supply the affected part — may be performed.

Crises

In the event of an acute ischaemic crisis (ie, where there is danger of the loss of tissue), the person should be directed to hospital immediately. Treatment includes vasodilation (eg, intravenous infusion of iloprost, oral nifedipine), pain relief (eg, lidocaine orbupivicaine), surgery and anticoagulation (eg, low-dose aspirin or short-term heparin if there is persistent critical ischaemia or occlusive disease of large arteries). Ischaemic crises are rare and most likely in patients with scleroderma.

Conclusion

For most people, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon is more an annoyance than a serious illness. It can usually be managed with lifestyle changes although some people need pharmacological intervention. Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon can be more difficult to manage and has a poorer prognosis, but drug treatment may help reduce the frequency or severity of attacks. Pharmacists can play a role by:

- Recognising symptoms and referring where appropriate

- Reassuring people (serious circulatory problems are uncommon)

- Being aware of drugs that can cause or worsen symptoms

- Giving advice on non-pharmacological strategies

References

- Bandolier. Raynaud’s Phenomenon Update. Available atwww.jr2.ox.ac.uk (accessed on 12 November 2007).

- Raynaud’s phenomenon. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Available at http://cks.library.nhs.uk (accessed on 12 November 2007).

- Suter LG, Murabito JM, Felson DT, Fraenkel L. The incidence and natural history of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the community. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2005;52:1259–63.

- Thompson AE, Pope JE. Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2005;44:145–50.

- Lamont P. Raynaud’s syndrome. Available at http://onlinesurgicaldictionary.com (accessed on 12 November 2007).

- Fries R, Shariat K, von Wilmowsky H, Böhm M. Sildenafil in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon resistant to vasodilatory therapy. Circulation. 2005;112:2980–5.

- Muir AH, Robb R, McLaren M, Daly F, Belch. The use of Ginkgo biloba in Raynaud’s disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Vascular Medicine 2002;7:265–7.

Resources

- The Raynaud’s and Scleroderma Association (www.raynauds.org.uk) provides support for patients and publications for health professionals.

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Cascade the relevant parts of this article to your staff. Do you stock products to help patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon (eg, heat pads)?

- Review the drugs that can cause Raynaud’s symptoms. Look for these when performing medicines use reviews.

- Incorporate information about Raynaud’s symptoms and peripheral vasoconstriction in your smoking cessation consultations

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?