This content was published in 2013. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s principles for medicines optimisation1 provide a new way of framing pharmaceutical care.

They challenge healthcare professionals to think differently about ways in which to help people make the best possible use of their medicines.

We propose that the wider use of simple risk-assessment tools to help identify patients at greater risk of medicines-related morbidity (MRM) will enable the principles of medicines optimisation to be put into everyday practice in a range of care settings.

The scale of the problem

In 2007, the National Patient Safety Agency estimated that medication errors cost the NHS approximately £750m per year.2 This is likely to be an underestimate of the true impact of MRM since data are derived from incidents that are reported, not those that actually occur. Estimates of the proportion of hospital admissions that are related to medicines vary considerably because data on MRM are not routinely collected. A UK study conducted in a hospital admissions unit reported that 6.5% of admissions were medicine-related and 67% of these were judged to be preventable.3 In their study, Pirmohamed et alsimilarly estimated that around 6% of admissions to two large English teaching hospitals were as a consequence of adverse drug reactions.4

While the resource implications for the NHS of managing the consequences of medicines- related morbidity are clearly considerable and the clinical consequences well recognised, the human cost is not so easily quantifiable.

Factors known to contribute to MRM

The causes of MRM are multifaceted and complex. A wide range of interdependent factors have been identified in the literature which we have classified broadly as:

Patient factors

Patient factors include: poor adherence to medicines prescribed; polypharmacy; discharge from hospital within the past three months; dependent living situation; older age; physical or mental disability; four or more co-morbidities; history of adverse drug reactions; and medicines allergy.

Medicines management systems and processes

Systems and processes include: inefficient management of repeat medicines; inadequate communication between healthcare professionals and patients; infrequent and inconsistent review of medicines; dispensing errors; inadequate monitoring of high risk drugs; and poor communication of medicines-related information at transfer of care.

Specific medicines

Four groups of drugs account for over 50% of hospital admissions related to medicines5 (non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin; anticoagulants, including warfarin; diuretics; and antidiabetic drugs, including insulin). A number of other medicines have also linked to MRM. The omission of essential medicines, such as those used in the management of severe infection, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy etc, should also be considered.

Interventions to reduce MRM

The multifactorial nature of MRM makes it unsurprising that evidence to support a single intervention to reduce MRM is lacking.6 However, there is good evidence that pharmacist-led interventions can identify those people at higher risk of MRM and allow targeting of effort.7 There is further difficulty in quantifying and evaluating the impact of interventions where the adverse outcome is an event avoided. In addition, risk assessment for MRM is undertaken neither consistently nor routinely at present. A recent paper by Kongkaew et al8 has called for better ways of identifying patients at high risk of preventable hospital admissions from adverse drug events.

Identifying patients at risk of MRM

Over the past five years, we have independently developed simple tools (available on PJ Online) that we have shown can be used for identifying patients at risk of MRM. Each tool is based on simple checklists, an approach commended in Atul Gawande’s book ‘The checklist manifesto — how to get things right’.9 Whereas the use of checklists is not unique, previous examples10,11 have tended to focus only on the medicines themselves. Our tools consider a variety of factors that are supported by both published literature and local experience. The tools involve a more holistic, patient-centred approach that allows those people at highest risk to be identified, which supports appropriate interventions being made and resources being deployed according to need. Local evaluation of data following the use of the tools in London and the West Midlands suggests that this approach can reduce MRM.

The risk factors in both tools were identified following a search of published literature and review by groups of clinical professionals as well as being informed by local practice. The tools were developed independently and their congruence supports their validity. We have successfully used them in a number of different ways depending on the care setting and the availability of services for medicines optimisation.

Supporting medicines optimisation

We have attempted to show how the use of our simple tools can support medicines optimisation by considering their use in the context of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s four principles of medicines optimisation as follows:

Principle 1 — Aim to understand the patient’s experience

We are able to identify people who are at risk of MRM and hence can focus the most appropriate support towards this cohort. For example, patients in whom adherence issues are identified as a specific risk can be supported through the use of techniques such as health coaching, to help them consider practical solutions and to address their beliefs and preferences about medicines. These patient-led conversations about medicines encourage shared decision making, inform treatment choices, promote appropriate self-care and provide a better patient experience.

Principle 2 — Evidence based choice of medicines

Medicines optimisation involves balancing the safe and evidence-based use of medicines with an overview of the patient’s needs and their preferences. The risk of MRM is increased through overuse, underuse or inappropriate use of medicines and through the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medicines or those of low therapeutic value, and our tools can help identify people at risk. For example, the tools highlight polypharmacy issues, which can increase MRM, particularly when there are incremental additions to a patient’s existing medicines following a succession of healthcare interventions as well as the purchase of over-the counter medicines.

Principle 3 — Ensure medicines use is as safe as possible

Through identification of patients at higher risk of MRM, these tools offer a method of optimising medicines to maximise safety and reduce avoidable harm. For example, medicines reconciliation can be prioritised in patients at higher risk of MRM. Similarly, patients for whom adherence is identified as a concern can be supported towards safe and confident medicines use and encouraged to discuss their queries and concerns about medicines.

Principle 4 — Make medicines optimisation part of routine practice

We have tried to develop practical tools that can be completed as part of everyday work. To date, they have been used by a range of healthcare professionals working in GP practices, hospitals, care homes and community pharmacies to optimise medicines. Identification, management and referral of higher risk patients facilitates better inter- professional communication and helps to maximise the NHS investment in medicines while reducing wastage.

Putting the approach into practice

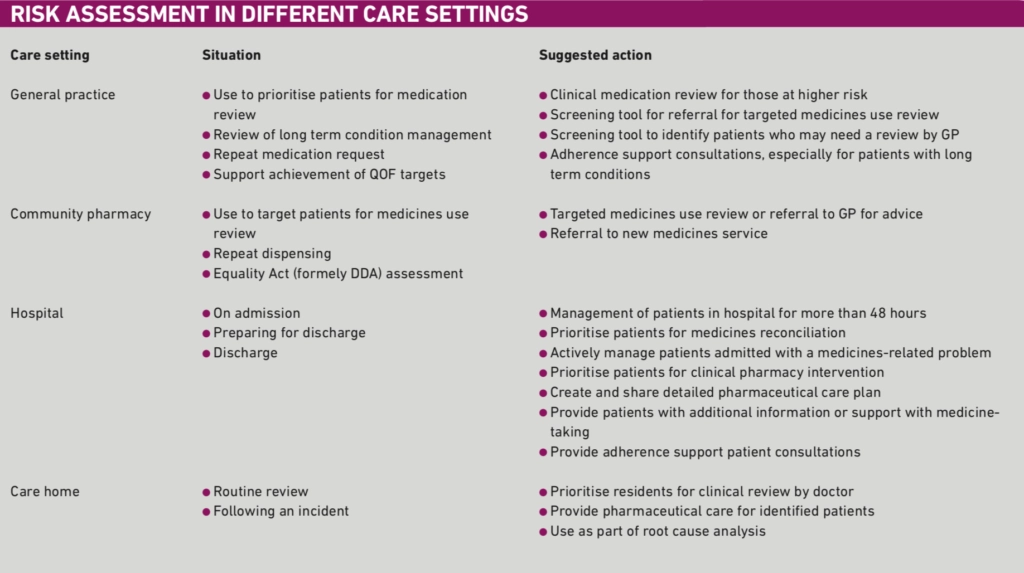

Table 1 provides some ideas about how the tools can be used in different care settings and, perhaps more importantly, suggests what actions might be taken as a result. These suggested actions can be adapted to suit local circumstances.

How these tools might be used in future

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has led the way in publishing the principles for medicines optimisation. We have described an approach that can be used to support the implementation of medicines optimisation in everyday practice. We believe that our respective tools will help pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in all sectors put the principles into practice.

References

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines optimisation. Helping patients to make the most of medicines. Good practice guidance for healthcare professionals in England. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013.

- National Patient Safety Agency. Safety in doses: medication safety in the NHS. The fourth report from the patient safety observatory. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2007.

- Howard RL, Avery AJ, Howard PD et al. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2003;12:280–85.

- Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–19.

- Howard RL, Avery AJ, Slavenburg S et al.Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2006;63:136–47.

- Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery AJ et al. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Qualityand Safety in Heatlh Care 2006;15:23–31.

- Avery A, Rogers S, Cantrill J. A pharmacist- led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost- effectiveness analysis. Lancet 2012;379:1310–9.

- Kongkaew C, Hann M, Mandal J et al. Risk factors for hospital admissions associated with adverse drug events. Pharmacotherapy 17 May 2013. doi: 10.1002/phar.1287 [epub agead of print].

- Gawande A. The checklist manifesto — how to get things right. London: Profile Books, 2010.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003;163:2716–24.

- Gallagher P, O’Mahoney D.STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age and Aging 2008;37:673–9.