Shutterstock.com

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) comprises a spectrum of liver disease ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to end-stage cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is strongly related to type 2 diabetes, obesity and insulin resistance, and this association has resulted in it traditionally being referred to as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome[1]

. However, there is now a growing body of evidence suggesting a more complex, bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and components of the metabolic syndrome, such as abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and abnormal glucose metabolism[2]

. NAFLD is now the commonest cause of chronic liver disease in developed countries[3],[4]

and worldwide prevalence is estimated to be in the region of 20%[4]

. Prevalence is much higher in those with type 2 diabetes where it is estimated to be around 70%[5]

, with prevalence figures in the UK very similar to those just mentioned, both for individuals with and without diabetes. NAFLD is also rapidly growing as an indication for liver transplantation and, in the United States, it is now the second commonest indication for this procedure[6]

.

Given such high prevalence, NAFLD represents a considerable challenge for healthcare services. This article will address diagnosis, assessment and management of people with NAFLD, including the management recommendations that formed part of the recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

What is NAFLD?

NAFLD can be defined as the presence of a hepatic triglyceride content of 5.5% or greater, a cut-off that corresponds to the 95th percentile in the Dallas Heart Study Cohort[7]

, and more recent studies have confirmed this figure[8]

. This simple hepatic steatosis may then progress to more serious forms of liver disease over time. Steatosis can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterised by steatosis existing alongside hepatocellular injury and inflammation, and may occur with or without fibrosis. It has been demonstrated that around 30% of individuals with hepatic steatosis will develop NASH over a 15–20-year period[9]

. NASH is indicative of more serious disease and in a Swedish cohort study has been demonstrated to be associated with a 14-fold increased risk of liver-related death when compared with a normal population, as well as a two-fold increased risk of death from a cardiovascular cause[10]

. Hepatic fibrosis, not other histological features, has been shown to predict liver-related mortality[11]

. Around a third of patients with NASH will then progress to liver cirrhosis over the following decade, with all the greatly increased morbidity and mortality that this brings, and of those individuals, 25% will develop serious complications related to portal hypertension within the next 3 years[12]

. Worsening liver disease also brings with it a markedly increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[13]

. One recent study looked at 195 individuals with NASH cirrhosis and found a yearly cumulative incidence of HCC of 2.6%, as compared with 4% in a cohort with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis over the same period[14]

. Additionally, it is known that HCC can occur secondary to NAFLD even in the absence of cirrhosis[15]

. There is evidence to suggest that type 2 diabetes is a significant risk factor for progressive worsening of liver disease in this context, as is the presence of adverse features of the metabolic syndrome[16],[17]

. There is also now a growing body of evidence that NAFLD is a multisystem disease, and it has a strong association with cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease[18]

.

What are the symptoms of NAFLD?

One of the key challenges with the management of NAFLD is that not only are the vast majority of patients with early disease asymptomatic, but a substantial proportion of those with serious liver disease also display either no symptoms or only vague, non-specific ones. Such symptoms, if present, may include fatigue and general lassitude, and a small minority may report abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant. If an individual has progressed to cirrhosis, then the characteristic signs of this may be present: spider naevi, palmar erythema, prominent abdominal veins and gynaecomastia (see Figure 1: Clinical signs of cirrhosis)[19]

. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for the first indication of a liver problem to be an episode of decompensated cirrhosis, at which point the diagnosis is much clearer. At this stage, clinical features can include jaundice, ascites, splenomegaly, nail changes and asterixis (see Figure 2: Clinical signs of decompensated cirrhosis). As the underlying diagnosis often only becomes apparent at an advanced stage of disease, it is vitally important to identify those individuals who are at high risk of progressing to more advanced stages of disease.

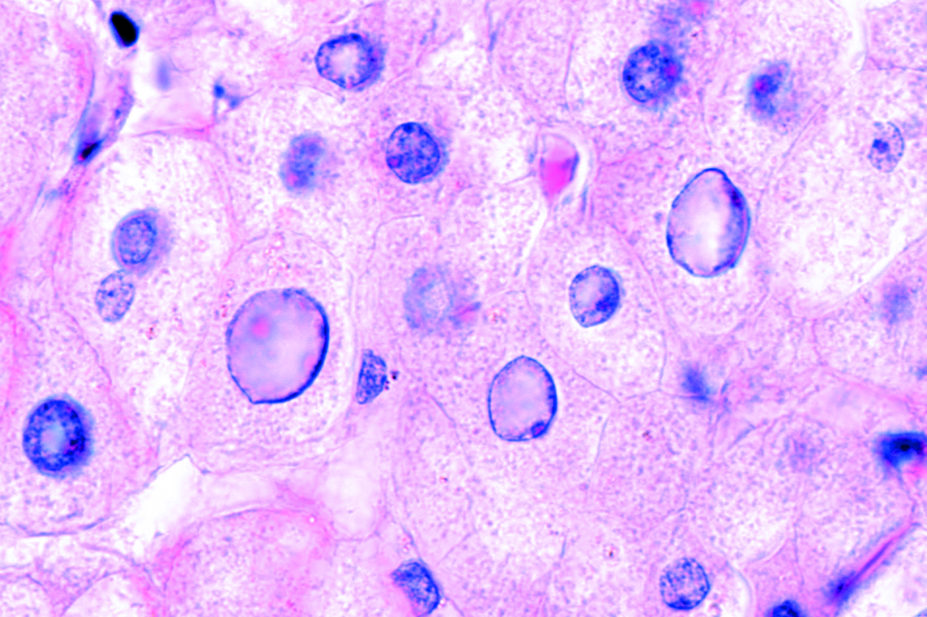

Figure 1: Clinical signs of cirrhosis

Source: Alamy Stock Photo, Science Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

1) Spider naevi (red spots with radiating extensions);

2) Palmar erythema (reddening of the palms);

3) Prominent abdominal veins;

4) Gynaecomastia (enlargement of male breast tissue).

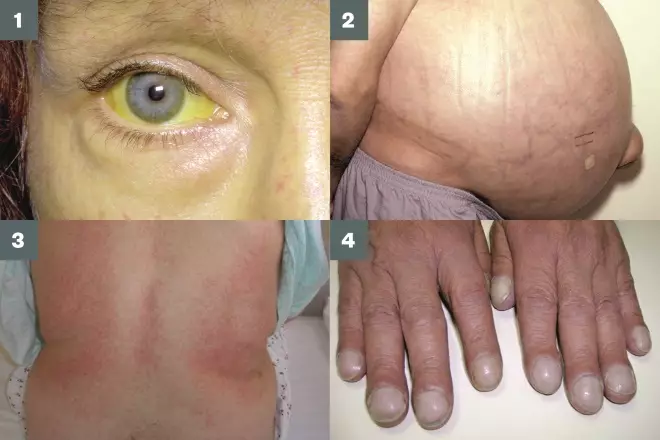

Figure 2: Clinical signs of decompensated cirrhosis

Source: Alamy Stock Photo, Wikimedia Commons

1) Jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin);

2) Ascites (fluid in the abdominal cavity);

3) Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen);

4) Nail changes (e.g. clubbing).

How is NAFLD diagnosed?

Diagnosing NAFLD remains problematic as there is no single, easily accessible diagnostic test with high sensitivity and specificity (see Table 1). The gold standard for diagnosis remains the liver biopsy; however, given the high patient numbers involved, this is not practical in health economics terms, and significant safety and acceptability issues remain with this procedure.

The most important aspect of diagnosis is an awareness of those individuals who are more likely to have NAFLD, namely those with type 2 diabetes or the metabolic syndrome. All individuals should be screened for alcohol consumption to exclude alcohol-related liver disease. It is important to be aware that standard biochemical liver tests, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase, are neither sensitive nor specific for a diagnosis of NAFLD. They cannot be used to exclude the diagnosis and, indeed, will be entirely normal in many individuals with NAFLD. However, it is worth considering that NAFLD is the commonest cause of elevated liver enzymes in those with type 2 diabetes, and 70% of people with NAFLD and type 2 diabetes will have abnormal liver enzymes[5]

.

Current NICE guidance on NAFLD, published in 2016, does not advocate routine screening using liver enzymes because there is no evidence to suggest that this is a useful approach[20]

. In general terms, NAFLD tends to result in a greater increase in ALT in relation to AST. This may be useful diagnostically in some cases because alcohol-related liver disease tends to result in a greater increase in AST in relation to ALT[21]

. Alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin tend to only become deranged in the presence of significant intrahepatic cholestasis, which may indicate more serious underlying liver pathology. Albumin and international normalised ratio (INR) are useful markers of synthetic liver function but are likely to remain normal unless an individual has progressed to cirrhosis[22]

.

Imaging studies may be used to look for hepatic steatosis, necessary for a diagnosis of NAFLD. Ultrasound scanning can identify steatosis and is a relatively low cost, safe and accessible investigation. It has a sensitivity of 84.8% and a specificity of 93.6% for the detection of moderate-to-severe fatty liver, although it is not as effective at detecting milder levels of steatosis[23]

. However, it should be noted that the level of hepatic steatosis correlates poorly with the risk of progression to more serious forms of liver disease such as NASH. Currently, the only way to reliably assess levels of inflammation and fibrosis in the liver is with histology of a biopsy sample, although this is rarely practical in routine clinical practice. In secondary care, techniques such as sonoelastography may be used as a way to non-invasively assess the extent of liver fibrosis[24]

.

Liver fibrosis markers are available to help determine which patients may be at higher risk for advanced fibrosis. Algorithms exist to assist primary care practitioners in determining which patients to refer for specialist advice[25]

. NICE recommends use of the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test as a non-invasive way to help to identify high-risk patients[20]

. This test generates a score based on concentrations of three biomarkers: amino terminal propeptide of type 3 procollagen (P3NP), hyaluronic acid (HA) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1). NICE advises using a cut-off of 10.51 at which level advanced fibrosis may be diagnosed, and such patients should be referred to specialist services.

| Table 1: Advantages and disadvantages of diagnostic tests for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Liver biopsy |

|

|

| Standard liver blood tests (e.g. alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) |

| |

| Ultrasound |

|

|

How should NAFLD be managed in the absence of significant fibrosis?

Most individuals with NAFLD will fall into the low-risk category, which includes those with no evidence of advanced fibrosis as indicated by their liver fibrosis marker score. These patients will overall be at low risk of progressing to more advanced liver disease[26]

. For these patients, the cornerstone of management is lifestyle change with an appreciation of the fact that they have increased cardiovascular risk (NAFLD has been identified as a strong independent cardiovascular risk factor)[4]

.

Patients should be advised to follow a hypocaloric diet, with a 600–800 daily reduction in calorie intake or a calorie restriction set to 25–30kcal/kg daily, calculated using ideal body weight[27]

. There is evidence to suggest that diets low in carbohydrate have additional benefits in reducing hepatic steatosis above and beyond simple caloric restriction[28],[29]

.

Weight loss of 5–10% is generally required to yield a measurable, clinically meaningful benefit. Such benefits might include improved insulin sensitivity, improvements in liver enzyme abnormalities and decreased histological evidence of inflammation. In addition, physical activity should be recommended to all people with NAFLD. Exercise has been shown to modify hepatic fat accumulation and improve insulin resistance[30]

. As a general rule, all people with NAFLD should be advised to aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate aerobic physical activity 3–5 times weekly, although caution is required for those with established cardiovascular disease, the elderly and those with mobility problems.

A large, observational study of more than 70,000 adults in South Korea recently showed that such a level of exercise is associated with a significantly reduced risk of developing NAFLD, as well as a reduction in liver enzyme concentration in patients who already had a diagnosis of NAFLD[31]

. As part of a general assessment of lifestyle, it is also important to enquire about quality of sleep, and patients with metabolic disease should be investigated for the possibility of obstructive sleep apnoea, where appropriate, because this can have a significant impact on outcomes[32]

.

Patients with NAFLD are generally advised to avoid alcohol; however, there is conflicting evidence regarding the validity of this advice[33]

. Certainly, patients should be advised regarding the potential harms of alcohol misuse. Due to increased cardiovascular risk and the higher prevalence of hypertension, patients’ blood pressure should be monitored and treated as with other high-risk populations, such as those with type 2 diabetes. Targets should be a systolic blood pressure of <130mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure of <80mmHg. Additionally, patients should be assessed for the presence of dyslipidaemia and treated in accordance with NICE guidelines on lipid modification[34]

. Many patients with NAFLD will require statin treatment on the basis of these guidelines, and healthcare professionals should be reassured that statins can safely be prescribed in this context providing the ALT is less than three times the upper limit of normality.

Specific pharmacological treatment for low-risk patients without evidence of fibrosis is generally not indicated owing to the paucity of evidence available and the relatively low likelihood that this population of patients will progress to more serious forms of liver disease. There is some evidence that bariatric surgery may be effective for the treatment of NAFLD[35]

; however, NAFLD does not currently feature in any criteria for assessing those who might benefit from such surgery. At the present time, possible improvement in parameters related to NAFLD could be considered a helpful secondary gain rather than a reason to recommend surgery in the first instance.

What treatment options exist for patients with NAFLD and significant fibrosis?

As described above, patients with NAFLD can have non-invasive testing in the form of liver fibrosis markers to assess their likelihood of having significant underlying fibrosis and, if present, patients are at increased risk of progressing to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. It is important to identify such patients because they may warrant referral into specialist secondary care services for further assessment and management. Recent NICE guidance has suggested consideration of pharmacological treatment with either vitamin E or pioglitazone for such patients within a secondary care setting[20]

, and other international guidelines are available to help guide clinicians[36]

. However, the evidence of long-term benefit for clinically meaningful outcomes associated with the use of these agents is not conclusive, and both have significant associated safety concerns.

There is evidence from two clinical trials to show that treating NASH patients with high-dose vitamin E can lead to improvements in both histology and liver biochemistry[37],[38]

. Treatment was noted to reduce histological steatosis, cellular ballooning and inflammation, all of which are hallmarks of NASH. Neither study, however, was able to demonstrate an improvement in fibrosis.

It is important to note that there are no data available to suggest that vitamin E prevents people with NASH from developing clinical liver cirrhosis or indeed that it is beneficial from a cardiovascular risk perspective. Additionally, there are significant concerns surrounding its long-term use, and a meta-analysis from 2005 concluded that high-dose vitamin E treatment may be associated with increased all-cause mortality[39]

. There are also data to suggest an association with the development of prostate cancer[40]

, although this has not been replicated in subsequent studies.

Thiazolidinediones are known to result in increased insulin sensitivity and these agents, in particular pioglitazone, have been suggested as treatments for NAFLD. There is evidence to suggest that thiazolidinediones can result in improvements to the whole spectrum of histological findings associated with NASH [41],[42],[43]

. However, as with vitamin E, there are no data to suggest that pioglitazone treatment reduces the risk of developing cirrhosis. Additionally, particular caution is advised when considering using pioglitazone because it is associated with weight gain, heart failure, osteopenia and possibly an increased risk of bladder cancer[44]

.

There are various other pharmacological agents currently in clinical trials that may be of use in the future — for example, obeticholic acid, a synthetic modified bile acid, which is a potent activator of the farnesoid X nuclear receptor. A recent randomised, placebo-controlled trial showed that it had a modest effect on liver histology in patients with non-cirrhotic NASH, but no data were available regarding clinically meaningful endpoints, such as liver-related morbidity and mortality[45]

. Another agent is cenicriviroc, which is a dual-selective inhibitor of C-C chemokine receptor (CCR) type 2 and 5. It is currently undergoing a Phase IIb clinical trial, and early data have suggested the possibility of anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic action due to an inhibition of monocyte effects and decreasing Kupffer cell activation, respectively[46]

.

How does NAFLD affect common anti-diabetic medication?

Chronic liver disease, particularly in cases of established cirrhosis, can have an impact on drug metabolism; this is of particular importance to anti-diabetic medications given the close association between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes. A multidisciplinary approach can be very useful in managing patients with NAFLD owing to their often multiple comorbidities, and pharmacists can play a very important role in helping decide which anti-diabetic medications may need particular attention.

Metformin should be used with caution in patients with cirrhosis, as there may be an increased risk of lactic acidosis[47]

. For this reason, UK recommendations are to avoid metformin in cirrhotic patients if they are at increased risk of tissue hypoxia, which would further increase the risk of lactic acidosis[48]

. It has also been suggested that the maximum daily dose in those with chronic liver disease should be reduced to 1,500mg[49]

. Insulin secretagogues undergo hepatic metabolism and, therefore, may have an increased duration of action when used in patients with cirrhosis. This can put the individual at significantly increased risk of hypoglycaemia; therefore, these agents should either be used at a reduced dose or avoided altogether[48]

. Despite its possible indication for use in NAFLD with fibrosis, there are also concerns around the use of pioglitazone in cases of established cirrhosis and currently, the British National Formulary advises avoiding it in such cases. Safety data for the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors in chronic liver disease are inconclusive, but most resources advise against the use of these classes of drugs in people with cirrhosis.

What is the role of liver transplantation?

Given that NAFLD is rapidly becoming the leading cause of cirrhosis worldwide, it is not surprising that it is now one of the leading indications for liver transplantation. Additionally, NAFLD is a strong risk factor for developing HCC, which may then be an indication for liver transplantation[13]

. Over the course of the last decade in the United States, the prevalence of NAFLD as an indication for liver transplantation has increased by 170%, and NAFLD is predicted to become the commonest indication for this procedure in the near future[50]

. Short-term outcomes are generally favourable with 1-, 3- and 6-month survival of 94%, 91% and 88%, respectively, when performed for NAFLD[51]

. Longer-term outcomes for liver transplantation in NAFLD are generally in line with that performed for other indications, such as viral or autoimmune hepatitis[50]

. It is likely that, going forward, liver transplantation will continue to have an important role in the management of NAFLD for patients who have progressed to end-stage liver disease or HCC.

Conclusion

NAFLD is a serious and growing public health concern that is closely linked to the ongoing epidemic of type 2 diabetes. It represents a spectrum of disease from simple hepatic fat infiltration, to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. Patients with multiple or severe features of the metabolic syndrome are at increased risk of progressive liver disease, and individuals who are at risk can be investigated non-invasively for the presence of significant fibrosis through the use of liver fibrosis markers. Patients with NAFLD in the absence of significant fibrosis should be managed with lifestyle optimisation and consideration of cardiovascular risk modification. Patients with significant fibrosis should be referred to specialist services for assessment and consideration of pharmacological treatment.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Kotronen A & Yki-Jarvinen H. Fatty liver: a novel component of the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:27–38. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147538

[2] Wainwright P & Byrne CD. Bidirectional relationships and disconnects between NAFLD and features of the metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:367. doi: 10.3390%2Fijms17030367

[3] Anstee QM, McPherson S & Day CP. How big a problem is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? BMJ 2011;343:d3897. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3897

[4] Targher G & Byrne CD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a novel cardiometabolic risk factor for type 2 diabetes and its complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:483–495. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3093

[5] Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762

[6] Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;148:547–555. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039

[7] Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R et al. Prevalence of steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 2004;40:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466

[8] Petäjä EM & Yki-Järvinen H. Definitions of normal liver fat and the association of insulin sensitivity with acquired and genetic NAFLD – a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17. doi: 10.3390%2Fijms17050633

[9] Musso G, Gambino R & Cassader M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver from pathogenesis to management disease: an update. Obes Rev 2010;11:430–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00657.x

[10] Ekstedt M, Franzen LE, Mathiesen UL et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology 2006;44:865–873. doi: 10.1002/hep.21327

[11] Angulo P. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015;149:389-397.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043

[12] Caldwell S & Argo C. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis 2010;28:162–168. doi: 10.1159/000282081

[13] Wainwright P, Scorletti E & Byrne CD. Type 2 diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors and pathogenesis. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17:20. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0851-x

[14] Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R et al. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:1972–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527

[15] Reeves HL, Zaki MY & Day CP. Hepatocellular carcinoma in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and NAFLD. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:1234–1245. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4085-6

[16] Adams LA, Sanderson S, Lindor KD et al. The histological course of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a longitudinal study of 103 patients with sequential liver biopsies. J Hepatol 2005;42:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.012

[17] Loria P, Londardo A & Anania F. Liver and diabetes. A vicious circle. Hepatol Res 2013;43:51–64. doi: 10.1111%2Fj.1872-034X.2012.01031.x

[18] Byrne CD & Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol 2015;62:s47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012

[19] Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2015; 313:2263–2273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5370

[20] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE Guideline [NG49]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): assessment and management. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng49 (accessed August 2017)

[21] Sattar N, Forrest E & Preiss D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ 2014;349:g4596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4596

[22] Perlemuter G, Bigorgne A, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Naveau S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathogenesis to patient care. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007;3:458–469. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0505

[23] Hernaez R, Lazo M, Bonekamp S et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 2011;54:1082–1090. doi: 10.1002/hep.24452

[24] Bota S, Herkner H, Sporea I et al. Meta-analysis: ARFI elastography versus transient elastography for the evaluation of liver fibrosis. Liver Int 2013;33:1138-1147. doi: 10.1111/liv.12240

[25] Sheron N, Moore M, Ansett S et al. Developing a ‘traffic light’ test with potential for rational early diagnosis of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in the community. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62: e616–624. doi: 10.3399%2Fbjgp12X654588

[26] Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z et al. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver versus nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13;643–654; e1–e9; quiz e39–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014

[27] Ueno T, Sugawara H, Sujaku K et al. Therapeutic effects of restricted diet and exercise in obese patients with fatty liver. J Hepatol 1997;27:103–107. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80287-5

[28] Browning JD, Baker JA, Rogers T et al. Short-term weight loss and hepatic triglyceride reduction: evidence of a metabolic advantage with dietary carbohydrate restriction. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:1048–1052. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007674

[29] Browning JD, Weis B, Davis J et al. Alterations in hepatic glucose and energy metabolism as a result of calorie and carbohydrate restriction. Hepatology 2008;48:1487–1496. doi: 10.1002/hep.22504

[30] Mager DR, Patterson C, So S et al. Dietary and physical activity patterns in children with fatty liver. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010;64:628–635. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.35

[31] Bae JC, Suh S, Park SE et al. Regular exercise is associated with a reduction in the risk of NAFLD and decreased liver enzymes in individuals with NAFLD independent of obesity in Korean adults. PLoS One 2012;7:e46819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046819

[32] Briancon-Marjollet A, Weiszenstein M, Henri M et al. The impact of sleep disorders on glucose metabolism: endocrine and molecular mechanisms. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2015;7:25. doi: 10.1186%2Fs13098-015-0018-3

[33] Liangpunsakul S & Chalasani N. What should we recommend to our patients with NAFLD regarding alcohol use? Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:976–978. doi: 10.1038%2Fajg.2012.20

[34] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guideline [CG181]. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 (accessed August 2017)

[35] Taitano AA, Markow M, Finan JE et al. Bariatric surgery improves histological features of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:429–437. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2678-y

[36] European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402: doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004

[37] Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N & Kowdley KV. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1675–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907929

[38] Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:1659–1668.doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.520

[39] Miller ER, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D et al. Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:37–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00110

[40] Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2009:301:39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864

[41] Promrat K, Lutchman G, Uwaifo GI et al. A pilot study of pioglitazone treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2004;39:188–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.20012

[42] Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Wehmeier KR et al. Improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazone. Hepatology 2003;38:1008–1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50420

[43] Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K et al. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2297–2307. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060326

[44] Taylor C & Hobbs FD. Type 2 diabetes, thiazolidinediones, and cardiovascular risk. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:520–524. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453440

[45] Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:956–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61933-4

[46] Marra F & Tacke F. Roles for chemokines in liver disease. Gastroenterology 2014;147:577–594.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.043

[47] Brackett C. Clarifying metformin’s role and risks in liver dysfunction. J Am Pharm Assoc 2010;50:407–410. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.08090

[48] Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, London. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnf/current/ (accessed August 2017)

[49] Khan R, Foster GR & Chowdhury TA. Managing diabetes in patients with chronic liver disease. Postgrad Med 2012;124:130–137. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2574

[50] Pais R, Barritt AS, Calmus Y et al. NAFLD and liver transplantation: current burden and expected challenges. J Hepatol 2016;65:1245–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.033

[51] Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V et al. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantations in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J Hepatol 2012;57:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.015