Science Photo Library

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of paracetamol in infants;

- Identify hepatotoxicity concerns and serious illness in infants;

- Describe the use of paracetamol for pain and as an antipyretic;

- Provide advice on the use and administration of paracetamol in infants and children.

Paracetamol is one of the most commonly administered medicines in children[1,2]. In a similar way to ibuprofen, its benefits as an analgesic and antipyretic, as well as its short-term safety profile, are widely known by both parents and healthcare professionals[3]. It is available for purchase as a general sales list medicine across the UK and is recommended alongside other over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics as a first-line treatment for fever and discomfort in young children[4,5].

Febrile illness is very common in preschool children, with 20–40% of parents presenting to healthcare professionals, including community pharmacies, with children experiencing symptoms of cough, cold, earache and fever each year[6].

Paracetamol is a safe medicine, when used at the right time and dose; however, safety concerns have been raised owing to its overuse by anxious parents attempting to reduce fever, reports of acute hepatotoxicity caused by accidental overdose or ingestion, and the possible link between paracetamol use in infancy and the development of asthma[2,7,8].

It is therefore essential that pharmacists educate parents and carers on the appropriate evidence-based use of all OTC analgesics, including information on their mechanism of action and administration, which are important in reducing errors and any risk of adverse effects.

Mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics

Despite the prevalent use of paracetamol for many decades, its full mechanism of action is still unknown[9]. There is evidence that it works via several central mechanisms, including effects on prostaglandin production, and across serotonergic, opioid, nitric oxide and cannabinoid pathways[9]. Its analgesic and antipyretic effects occur through the inhibition of prostaglandin production centrally; however, unlike non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs it has little anti-inflammatory effect[9].

Absorption

Oral formulations have a high bioavailability, with 70–90% of the dose absorbed[10]. The time for peak serum levels post-oral administration is similar for both children and adults, and is dependent on the speed of gastric emptying[1]. Food delays absorption; therefore, it can be given on an empty stomach to achieve a quicker onset of action[1]. It is well absorbed by the rectal route; however, this has a lower bioavailability than oral absorption[1].

Distribution

Paracetamol is widely and quickly distributed in the body, and rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier to exert its central analgesic effect[1]. Distribution is greatest in preterm infants, before reducing with maturity until reaching the same levels as adults at around one year of age[1].

Metabolism

Paracetamol is metabolised in the liver, predominantly by glucuronidation and sulfation to non-toxic conjugates that are renally excreted[9]. The glucuronidation pathway is not fully developed at birth and may take up to two years to mature; therefore, the majority of paracetamol is metabolised in infants by the sulfation pathway and a small amount is oxidised via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system to form the highly toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI)[9,11]. NAPQI is then conjugated with glutathione and renally excreted. CYP enzymes are less developed in neonates and young children, resulting in smaller amounts of NAPQI formation[1]. However, where glutathione levels may be lower (e.g. in malnutrition), or insufficient, a paracetamol overdose could cause higher levels of NAPQI, resulting in acute hepatotoxicity[1,9].

Elimination

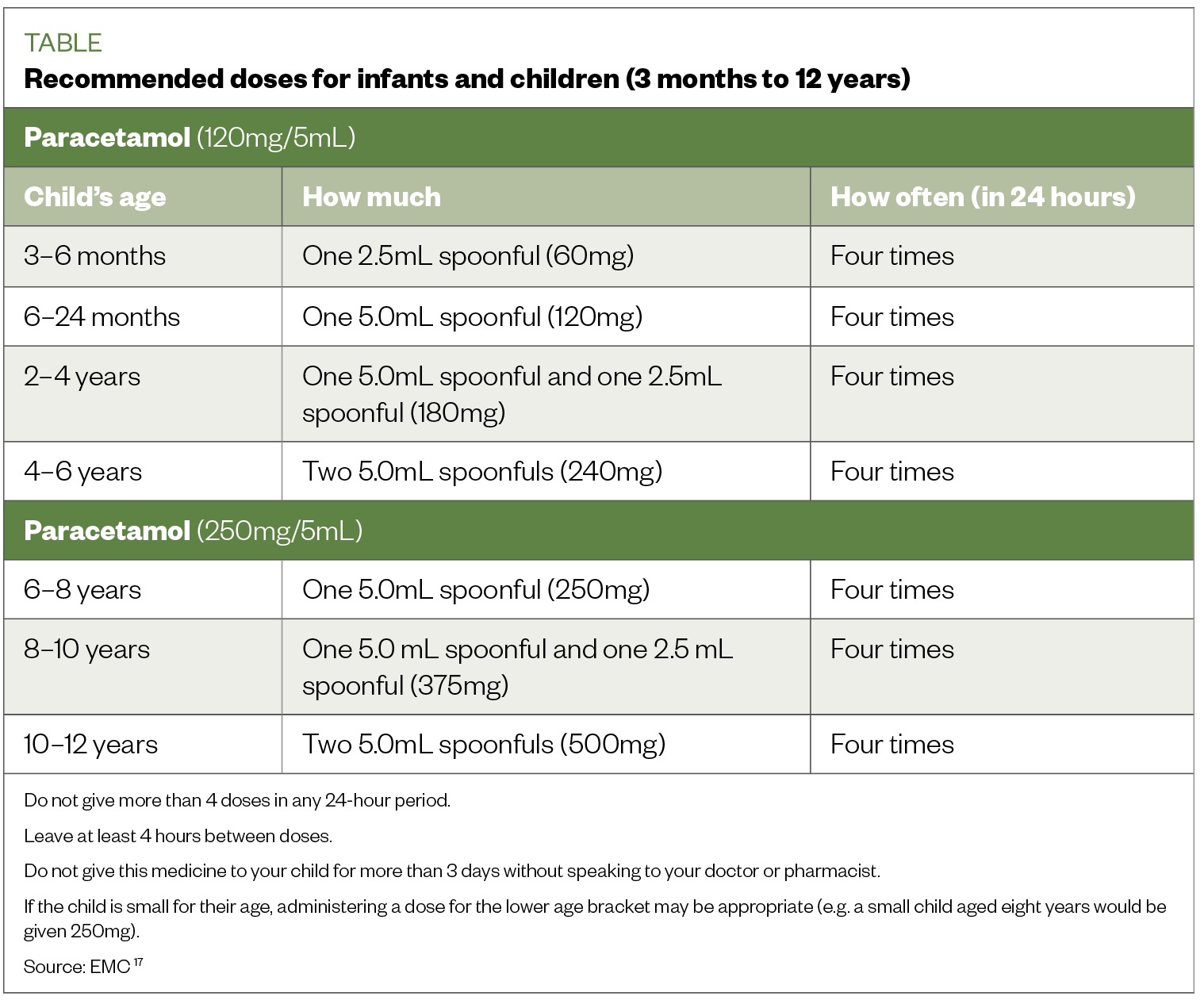

The elimination half-life of paracetamol is longer in neonates than older children and is reflected in the frequency of recommended dosing (see Table)[9,12]. Regardless of age, in all patients with a reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate, frequency of doses should be capped at every six hours, owing to delays in the elimination of glucuronidation and sulfation conjugates[12].

Hepatotoxicity concerns

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity is rare in infants and children when used at recommended doses[9]. It has been suggested that neonates have an unexpected, conferred protection from hepatotoxicity owing to paracetamol, even when given in large therapeutic excess, potentially explained by their increased ability to produce glutathione rapidly and slow oxidative metabolism[13]. Several studies have highlighted medication errors by carers, parents and healthcare professionals that have resulted in the development of acute liver failure in children after receiving an overdose of paracetamol[14–16].

A review of VigiBase reports (n=200) of suspected fatal adverse drug reactions to paracetamol in children aged under 5 years found that 30% were associated with medication errors (e.g. accidental overdose by a parent, carer or healthcare professional, accidental ingestion by the child and incorrect drug administration)[15]. Rajanayagam et al. retrospectively analysed 14 cases of paediatric acute liver failure that were associated with paracetamol overdose; 12 of the children were aged under 5 years[16]. The review highlighted common administration errors linked to parental accidental overdose, resulting in hepatotoxicity (see Box 1)[16].

Some medications may increase the risk of paracetamol hepatotoxicity, including those that induce liver enzymes (e.g. in children taking medicines for epilepsy or tuberculosis)[17]. Medicines that induce liver enzymes (e.g. phenobarbital, phenytoin) may also reduce the effectiveness of paracetamol[18].

Box 1: Reported paracetamol administration errors by caregivers

- Children receiving double doses;

- Co-administration of other paracetamol containing preparations;

- Exceeding recommended daily dosage;

- Increased dose frequency.

Reported reasons given by caregivers for these errors were:

- Failure to read and understand labelled instructions;

- Use of incorrect measuring devices;

- Wrong strength of paracetamol syrup given or use of adult tablets;

- Lack of recognition of paracetamol in other common ‘cold remedies’[15,16].

Confirming appropriateness

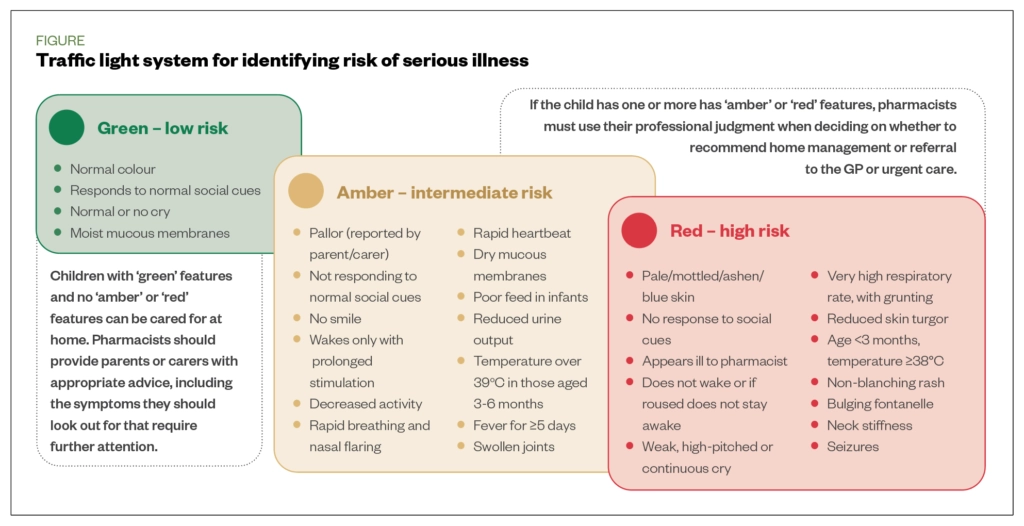

Before recommending any OTC medicine for any indication, it is essential that pharmacists and their teams assess the child for risk of life-threatening and serious illnesses, including meningitis and sepsis. This assessment may not include a physical examination, owing to scope of practice, and is therefore based on an interpretation of symptoms rather than physical signs[6]. As physical signs of serious illness in infants and young children are difficult to assess and recognise, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence traffic light system can help when triaging patients, but should be used with professional judgment when deciding an appropriate course of action (see Figure)[6].

Paracetamol may mask a fever owing to other underlying causes, such as systemic bacterial or viral infection; therefore, parents/carers should not delay in seeking medical advice[19]. Online or telephone appointments for unwell children with amber or red features, and infants aged under three months, should only be offered to triage referral for medical review and physical assessment[20]. For infants aged under three months, there should be a low threshold for referral for medical review, especially where there is parental anxiety[6].

Use of paracetamol

Paracetamol is safe to give to most children; lower doses may be required for those who are small for their age, or who have liver or kidney disease[12]. It can be used in children from two months of age for fever related to immunisations, and from the age of three months for fever and pain[6,12]. In addition, ibuprofen may be used in children aged over three months for the management of fever[6]. In an otherwise well child, if one antipyretic is not effective it can be switched to another. Alternating agents can be recommended if distress persists or occurs before the next dose is due. Both agents should not be given for fever simultaneously[5].

Paracetamol is available orally in two strengths of liquid: 120mg/5ml for children aged <6 years and 250mg/5ml for children >6 years[12]. It is also available as melt-tab and rectal formulations; therefore, it is important to ensure the correct strength has been selected[12]. The Table shows the recommended doses for paracetamol oral suspension for children[18].

Intravenous paracetamol is available for hospital use for the management of severe pain and may also be used in some neonatal units ‘off label’ to close a patent ductus arteriosis in premature babies[12,21].

Immunisation

Fever is a common side effect associated with vaccination, particularly the meningitis B vaccine, peaking at 6 hours post-vaccination[22]. It is usually gone after 48 hours. Paracetamol is currently recommended for post-immunisation fever following the meningitis B vaccination; dosing advice differs when used following other routine vaccinations — parents can be advised to administer up to three doses, which may differ from the advice provided on the product information. Further important counselling points can be found in Box 2[23].

Box 2: Advice for parents after baby’s meningitis B vaccination

- Some babies may develop fever after vaccination, which may still be present after having three doses of paracetamol. In the 48 hours after vaccination, if a child still has a fever but is otherwise well, the same 2.5 mL dose (60mg) of infant paracetamol (120mg/5ml) suspension can be continued;

- Doses should be given at least 4 hours apart and no more than 4 should be given in any 24-hour period;

- Keep babies cool by removing unnecessary layers of clothes or blankets, and ensure they have plenty of fluids. If they are breast-fed, the best fluid to give is breast milk;

- If a baby still has a fever or is unwell more than 48 hours after vaccination, advise the parent to speak to their GP or call 111 in England and Scotland, and 0845 4647 in Wales for advice[23].

General advice

By understanding the evidence-base underpinning guideline recommendations and the quality of clinical data, pharmacists and their teams can provide appropriate, practical advice and support to parents and carers regarding paracetamol administration and appropriate dosing (see Box 3).

Box 3: Advice to support parents and carers with paracetamol administration and appropriate dosing

Practical advice on the use of paracetamol in young children:

- The systems in a child’s body are immature compared to an adult’s; however, paracetamol has a proven safety profile when given at recommended doses for short durations;

- Antipyretics should not be given with the sole aim of reducing fever. Fever does not need to be treated if a child is content; it is the body’s natural response to an infection. Only give paracetamol if the fever is making the child uncomfortable or distressed[7];

- There are different types of paracetamol, including two strengths of oral syrup. The strength and dosage depend on the child’s age (and sometimes weight), so always read the instructions carefully;

- If the child has a low weight for their age, the correct dose should always be confirmed;

- Keeping a written record of what doses are given, and when, can reduce the likelihood of repeating a dose earlier than intended.

Administering liquid paracetamol to infants using an oral syringe:

- Check the strength of the medicine you have and the dose for the child, as paracetamol is available in more than one strength;

- Measure the correct dose using an oral syringe. Do not use a kitchen teaspoon as it will not give the right amount;

- The medicine should be administered when the parent and baby are calm. The syringe should be placed in the side of the baby’s mouth and gum, with the tip pointed towards the cheek and the plunger pressed slowly, making it harder for them to spit the medicine out;

- If the child does not like the taste, a drink of milk can be given straight after the dose;

- Further advice, including demonstration videos can be found on the Medicines for Children website.

Best practice

To ensure risks to children are minimised, pharmacists must follow best practice to ensure paracetamol is only given when needed, promote clear dosing recommendations and ensure parents are given clear instructions on administration and supplementary information to safety net as follows:

- Virtual consultations are not appropriate to assess an unwell child. If you believe a child has red or amber symptoms (see Figure), refer promptly for a face-to-face medical consultation[20];

- Children aged under three months with a temperature of 38°C or higher are in a high-risk group for serious illness and should be referred for urgent medical attention (note that some vaccinations have been found to induce fever in children aged under three months, however owing to the high-risk nature of this age group, these children should still be urgently referred);

- Antipyretics should not be given with the sole aim of reducing fever. Treatment should only be considered if the child is distressed or in discomfort;

- Explain to parents in clear terms the dose of paracetamol to administer and how often, and recommend recording the times and doses given to prevent unintentional overdoses;

- If there is any possibility that a child may have had more than a double dose of paracetamol, or you are not sure, contact NHS services (111 in England and Scotland; 0845 4647 in Wales) or refer the child to hospital immediately;

- Parents should be given appropriate advice and support, and provided with safety netting advice on warning symptoms and signs of severe illness, including when medical review is needed.

Useful resources:

- The Pharmaceutical Journal has partnered with health and hygiene company RB to provide free and open resources for pharmacy teams to better serve patients seeking advice for acute pain. These include:

- Other resources:

This article has been reviewed by the expert author to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in February 2021.

- 1Moriarty C, Carroll W. Paracetamol: pharmacology, prescribing and controversies. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2016;:331–4. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-307287

- 2Star K, Choonara I. How safe is paracetamol? Arch Dis Child 2014;:73–4. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-307431

- 3Kanabar DJ. A clinical and safety review of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children. Inflammopharmacol 2017;:1–9. doi:10.1007/s10787-016-0302-3

- 4Fever in under 5s. Quality standard [QS64]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs64 (accessed Feb 2021).

- 5Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. NICE Guideline [NG143]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng143 (accessed Feb 2021).

- 6Feverish children – management. Prevalence. Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/feverish-children-management/ (accessed Feb 2021).

- 7Templeton S-K. Children put at risk as parents misuse Calpol. The Times. 2015.https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/children-put-at-risk-as-parents-misuse-calpol-kdrlgtn0v8t (accessed Feb 2021).

- 8Magnus MC, Karlstad Ø, Håberg SE, et al. Prenatal and infant paracetamol exposure and development of asthma: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2016;:512–22. doi:10.1093/ije/dyv366

- 9Sharma CV, Mehta V. Paracetamol: mechanisms and updates. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2014;:153–8. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkt049

- 10Forrest JAH, Clements JA, Prescott LF. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Paracetamol. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1982;:93–107. doi:10.2165/00003088-198207020-00001

- 11Cook SF, Stockmann C, Samiee-Zafarghandy S, et al. Neonatal Maturation of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Glucuronidation, Sulfation, and Oxidation Based on a Parent–Metabolite Population Pharmacokinetic Model. Clin Pharmacokinet 2016;:1395–411. doi:10.1007/s40262-016-0408-1

- 12Paracetamol. Paediatric Formulary Committee. BNF for children. London: BMJ Group, Pharmaceutical Press, and RCPCH Publications. 2020.https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drug/paracetamol.html (accessed Feb 2021).

- 13Isbister GK. Paracetamol overdose in a preterm neonate. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2001;85:70F – 72. doi:10.1136/fn.85.1.f70

- 14Sutcliffe K, Stokes G, O’Mara-Eves A et al. Paediatric medication error: A systematic review of the extent and nature of the problem in the UK and international interventions to address it. 13. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education. 2014.https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/Paediatric%20medication%20error%202014%20Sutcliffe%20report.pdf?ver=2014-11-20-161504-377 (accessed Feb 2021).

- 15Lindquist M. VigiBase, the WHO Global ICSR Database System: Basic Facts. Drug Information J 2008;:409–19. doi:10.1177/009286150804200501

- 16Rajanayagam J, Bishop JR, Lewindon PJ, et al. Paracetamol-associated acute liver failure in Australian and New Zealand children: high rate of medication errors. Arch Dis Child 2014;:77–80. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304902

- 17Shi Q, Yang X, Greenhaw JJ, et al. Drug-Induced Liver Injury in Children: Clinical Observations, Animal Models, and Regulatory Status. Int J Toxicol 2017;:365–79. doi:10.1177/1091581817721675

- 18Paracetamol 120mg/5ml Oral Suspension. . Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2019.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9274/smpc#gre (accessed Feb 2021).

- 19Russell F, Shann F, Curtis N, et al. Evidence on the use of paracetamol in febrile children. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:367–72.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12856055

- 20Using Online Consultations in Primary Care Implementation Kit. NHS England. 2020.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/online-consultations-implementation-toolkit-v1.1-updated.pdf (accessed Feb 2021).

- 21Ohlsson A, Shah PS. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Published Online First: 27 January 2020. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010061.pub4

- 22Meningococcal: the green book, chapter 22. Public Health England. 2016.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/554011/Green_Book_Chapter_22.pdf (accessed Feb 2021).

- 23Using Paracetamol to prevent and treat fever after MenB vaccination. Public Health England. 2018.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/717281/PHE_paracetamol-menB-A4-2018_01.pdf (accessed Feb 2021).

You might also be interested in…

GPhC writes to pharmacy teams after methotrexate dispensed with instruction to take once daily

Medicines commission calls for greater clarity on risk of suicidal behaviour from antidepressants