GARO / PHANIE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Discuss the different symptoms associated with the different stages of perimenopause;

- Recognise the age of onset and duration of perimenopause;

- Identify the most appropriate therapy for symptom management;

- Explain the benefits and risks associated with therapy, including hormone replacement therapy.

Perimenopause is a transitional state describing the period preceding menopause, with accompanying endocrinological, biological and clinical features[1–3]. The terms ‘perimenopause’ and ‘menopausal transition’ can be used interchangeably[2]. Menopause, although commonly used to describe perimenopause, is characterised by 12 consecutive months of amenorrhoea, marking reproductive senescence[4–6].

In England and Wales, 51% of the population are women[7]. A recent call for evidence for the first-ever government-led Women’s Health Strategy for England identified a need for education and training of healthcare professionals in women’s health, in particular menopause and hormone replacement therapy (HRT)[8]. The research report found that symptoms associated with menopause were not always recognised or taken seriously, with some GPs reluctant to prescribe HRT.

In the UK, the average age of menopause is 51 years[9]. Although the median duration of perimenopause is four years, it can occur for more than a decade preceding menopause[6]. Perimenopause can be more symptomatic and more difficult to treat than post-menopause, significantly impacting affected women’s quality of life[2,10]. As many as 85% of women experience physical and/or psychological symptoms during perimenopause[11]. Symptoms and severity can vary, and almost 90% of these women will seek advice on symptom management from healthcare professionals[3,12,13].

Pharmacists must adopt an evidence-based approach to managing symptoms of perimenopause: recognising and managing symptoms, explaining the benefits and risks of therapy, and referring as and when required.

The menstrual cycle

There are two phases of the menstrual cycle: the follicular (proliferative) phase and the luteal (secretory) phase. The median duration of a menstrual cycle is 28 days, with most cycles ranging from 25 days to 30 days. This variability in cycle length is predominantly owing to varying lengths of the follicular phase (i.e. 10–16 days); the luteal phase tends to be relatively stable[14].

Hormones produced in the pituitary gland — luteinising hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone — regulate the menstrual cycle. Together, luteinising hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone promote ovarian follicle growth, ovulation and ovarian production of oestrogen and progesterone. Oestrogen and progesterone prime the uterus for possible endometrial blastocyst implantation[15,16].

Physiology of perimenopause

Perimenopause is conventionally divided into early and late phases (see ‘Diagnosis’ below)[17]. Endocrine changes during perimenopause are primarily responsible for the associated physiological changes[17,18]. A decline in the number of ovarian follicles results in a decrease in the levels of inhibin B, anti-Mullerian hormone and ovarian oestradiol[17,19]. Declining oestrogen levels are probably responsible for the vasomotor symptoms (e.g. hot flushes) associated with late perimenopause and the subsequent failure of endometrial development results in irregular menstrual cycles[19]. Importantly, the decline in oestrogen during perimenopause is not steady: oestrogen levels fluctuate widely, almost on a daily basis[20–22].

Menopause and associated amenorrhoea result from a reduction in the number of ovarian follicles and the subsequent loss of ovarian follicular activity[17]. Because oestrogen and inhibin B have an inhibitory effect on gonadotrophins, the production of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone increases, ovulation does not occur, oestrogen production is decreased and menstruation ceases[17,19].

After menopause, follicle-stimulating hormone levels are raised, oestradiol levels are decreased and inhibin B and anti-Mullerian hormone levels are undetectable[17].

Diagnosis

Perimenopause is diagnosed clinically. A thorough history, including menstrual cycle and symptoms (e.g. vasomotor symptoms, irregular periods), rather than laboratory results, in healthy women aged over 45 years is required[9]. Measurement of reproductive hormone levels is of little clinical benefit. During perimenopause, two-fold higher than normal levels of oestradiol, extremely low levels of oestradiol and abnormally frequent ovulatory episodes have all been associated with irregular cycles[2,9,23]. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has explicitly stated that laboratory tests, including the following, are not required to diagnose perimenopause in women aged over 45 years[9]:

- Anti-Mullerian hormone;

- Inhibin A;

- Inhibin B;

- Oestradiol;

- Antral follicle count;

- Ovarian volume;

- Follicle-stimulating hormone.

STRAW+10 staging system

The STRAW+10 staging system, a revision and update of the ‘Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop’ (STRAW) staging system, characterises the reproductive aging of women through to post-menopause (stage –5 through to stage +2)[24]. According to STRAW+10, perimenopause covers early menopausal transition (stage –2), late menopausal transition (stage –1) and the first (stage +1a) of the 3 stages (+1a, +1b, +1c) of early post-menopause.

In STRAW+10, the duration of ‘early’ menopausal transition (stage –2) is variable, with the principal criteria of ‘variable’ menstrual cycle length and a ≥7-day difference in length of ‘consecutive’ menstrual cycles. No symptoms (e.g. vasomotor symptoms) are listed for descriptive characteristics in early perimenopause. Listed supportive criteria are: variable and elevated follicle-stimulating hormone, low anti-Mullerian hormone and low inhibin B levels.

The duration of late menopausal transition (stage –1) is 1–3 years, with the primary criterion of ≥60 days of amenorrhoea during the menstrual cycle. Vasomotor symptoms are listed as descriptive characteristics with the following supportive criteria: elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (>25 IU/L), low anti-Mullerian hormone, and low inhibin B.

For the first (stage +1a) of the three stages of post-menopause (stages +1a, +1b, +1c), which is also the last of the three stages of perimenopause, vasomotor symptoms are listed as ‘most’ likely.

Symptoms

There is no uniform experience of perimenopause. Symptoms, symptom severity, menstrual cycle and menstrual flow vary significantly between women. Ethnic, cultural, religious, personal, sociological and nutritional status can affect both the intensity and the incidence of symptoms[2,25,26].

A recent multinational study (UK, Europe, Australia) found that more UK women experienced symptoms than women in any other European country. Symptoms, in general, were found to potentially have substantial negative effects on quality of life[26].

Women generally experience more symptoms during perimenopause than post-menopause, possibly owing to erratic hormonal fluctuations[2,27]. Erratic increases in oestradiol and inconsistent levels of progesterone are probably responsible for symptoms of both oestrogen excess (e.g. headaches, migraines, breast tenderness, menstrual flooding) and oestrogen deficiency (e.g. vaginal dryness, vasomotor symptoms). Other symptoms include, but are not limited to, sleep and mood disorders, anxiety, fatigue, arthralgia and gastrointestinal symptoms[2,28].

Women who experience early-onset perimenopause (i.e. before the median age of 47 years) and cycle irregularity are more likely to be symptomatic, and experience a longer perimenopausal period, compared with women with later-onset perimenopause[29]. More variable hormone levels over time are also associated with more symptoms[30]. Further, body mass index (BMI) and race may have an impact on hormone levels. An association between obesity and lower levels of luteinising hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, oestradiol and progesterone, in addition to decreases in urinary hormone metabolite excretion, have been found[31]. And, in one study, African American and Hispanic women had higher levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and testosterone, compared with other ethnic groups[18]. Symptoms associated with perimenopause can be indicative of other pathologies, so management of perimenopausal symptoms should involve the exclusion of differential diagnoses.

Menstrual flow and cyclicity

During perimenopause, it can be difficult to distinguish normal menstrual bleeding from abnormal menstrual bleeding, because of variations in bleeding patterns between women[18]. There can be a wide variation in menstrual flow and cyclicity owing to ‘erratic’ peaks of oestradiol and inconsistent luteal phase levels of progesterone[23]. Menstrual cycles are not always longer: in early perimenopause, defined by STRAW criteria stage –2 (see section on ‘diagnosis’, above), short cycles of <21 days are more common[18,24]. Longer cycles of >36 days are more common in late perimenopause (STRAW criteria stage –1)[18,24]. Increased rather than decreased length of menstrual bleeding is also more likely: in the SWAN prospective cohort study, 77% of women reported at least 3 episodes of bleeding lasting for more that 10 days[32].

Headaches and migraines

The prevalence of migraine in childhood is the same for both biological sexes[33]. After puberty, the prevalence of migraine in women increases, with prevalence three to four times higher in women compared with men[34–36]. The effect of hormonal fluctuations on migraine is so pronounced that menstrual migraine is recognised, by international classification, as a distinct headache disorder[37].

Perimenopause is associated with an increased susceptibility to migraines[38,39]. Fluctuating oestrogen levels are probably responsible, and progesterone’s attenuation of pain responses may further compound this. Several studies have indicated that migraines during perimenopause are longer, more severe, have more associated symptoms and are less responsive to acute medication compared with non-menstrual migraines[40–43]. Although perimenopausal migraine is not recognised as an independent clinical condition; treatment options for menstrual migraine and perimenopausal migraine follow the same principles[33].

Mood disorders

Hormone fluctuations during perimenopause can cause psychiatric symptoms[44]. Perimenopause has been associated with mood disorders (e.g. depressive disorders, bipolar disorder) and, although first onset is multifactorial during perimenopause, it is influenced by hormonal fluctuations, especially oestrogen[44]. Oestrogen acts as a serotonergic agonist and modulator, increasing synthesis and uptake[45,46]. Fluctuating levels of both oestrogen and progesterone affect the serotonin and neuronal networks and therefore mood[44]. Depressed mood during perimenopause, including new-onset major depressive disorder and anxiety, has been demonstrated in three robust longitudinal studies[47–49]. Further, women are two to four times more likely to experience major depression during and immediately after perimenopause, even after controlling for prior history of major depression, medication use, vasomotor symptoms and very life upsetting events[47,50].

Insomnia

Sleep disorders, trouble falling asleep, interrupted sleep and early awakening are very common during perimenopause: 37% of women aged 40–55 years have reported difficulty sleeping[18,51]. Women with sleep disturbances prior to perimenopause tend to have worsening sleep symptoms throughout perimenopause, only stabilising post-menopause[52]. Although hormone levels do not seem to be associated with sleep disturbances, there is a strong association with stress, lifestyle factors, psychological and vasomotor symptoms[19]. Other conditions associated with perimenopause, such as depression and anxiety, can also cause early awakening. Fatigue, another common complaint during perimenopause, may be a result of sleep quality and variance of sleep[18].

Cognitive function

Oestrogen acts on the cholinergic system, promoting neuronal growth and neuronal survival. And, although the pre-frontal cortex supporting cognitive function may be particularly sensitive to oestrogen, cognitive changes and severity of these changes during perimenopause is not well understood, nor are the effects of fluctuating hormones on cognition[22]. Many women report forgetfulness and difficulties in concentration during perimenopause[53]. There is evidence to suggest that while pre- and post-menopausal women demonstrated improvements with repeated tests for verbal memory and processing speed, perimenopausal women did not[54]. However, other studies have not consistently shown significant differences in women at different menopausal stages[22].

Arthralgia

The prevalence of arthralgia in women appears to increase during perimenopause[30,55]. And, although the incidence of rheumatological disease and joint discomfort increases with age, there is an association of joint pain with perimenopause[5]. Joint pain and stiffness have been reported as some of the more prevalent and bothersome symptoms and may be a result of decreasing oestrogen levels[30,55–61].

Gastrointestinal symptoms

During perimenopause, women experience gastrointestinal symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhoea, gastro-oesophageal reflux, abdominal pain and bloating[62,63]. Studies on gastrointestinal symptoms in women at various ages support an association with perimenopause[62,64–66]. Further, both intestinal function and transit speed can be affected by ovarian hormones[67].

Vasomotor symptoms

Approximately 80% of women experience hot flushes, or hot flashes, during perimenopause[68–70]. Hot flushes usually last for up to five minutes, but can last for up to an hour[71]. They have been described as sudden feelings of warmth or heat, especially in the upper body (e.g. face, neck, chest), that are accompanied by peripheral vasodilatation, profuse sweating and sometimes followed by a chill[18,71]. Hot flushes are partially mediated by oestrogen depletion during late perimenopause[71]. Experience of hot flushes seems to be influenced by race and ethnicity, with the highest reported prevalence in white women and the lowest in Japanese and Chinese women. Obesity also appears to be a factor: a higher BMI has been associated with worse symptoms[18,71,72].

Genitourinary symptoms

Deceasing oestrogen levels are associated with a decrease in vaginal collagen, hyaluronic acid and elastin content, thinned epithelium and increased vaginal pH[73]. Vaginal dryness, atrophy, dyspareunia and urinary symptoms, although more common post-menopause, also affect women during perimenopause[18]. Vaginal dryness can cause pain during sexual intercourse, affecting sexual function and quality of life[74]. In one study, 40% of women who reported vulvovaginal symptoms also reported sexual dysfunction[75].

Other symptoms

Other symptoms during perimenopause that may be affected by fluctuating hormones include: melasma (hyperpigmentation of the skin), mastalgia (breast swelling and tenderness), alopecia (scalp hair loss), formication, myalgia, weight gain and central adiposity[9,76–80].

Management

A holistic, patient-centred approach should be adopted when managing symptoms of perimenopause. Before commencing therapy (including HRT), the benefits and risks of treatment should be explained with consideration to the individual woman’s literacy and health literacy. Women from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds can have lower literacy levels and are less likely to be treated for their perimenopausal symptoms[81,82]. To facilitate health equity, pharmacists should take care to adjust their language to suit the individual patient. Risks of HRT can be found in NICE guidelines and resources from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (see Table[9,83]).

Symptomatic management will depend on the stage of perimenopause and patient preference. Pharmacists, after a risk–benefit assessment and provision of appropriate education and counselling, should facilitate shared decision making. Higher oestrogen levels during early perimenopause are associated with menorrhagia, mastalgia, weight gain and headaches. Vasomotor symptoms and vaginal dryness more commonly accompany lower oestrogen levels during late perimenopause[2]. Symptoms should be regularly monitored and treatment adjusted as required[9].

Psychological symptoms

HRT and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) should be considered to alleviate low or depressed mood. Additionally, CBT should be considered to manage anxiety. In the absence of a diagnosis of depression, there is currently no evidence to support prescribing selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) to alleviate low mood[9]. Guidance is available from the British Menopause Society and NICE on alternatives to HRT, including SSRIs and SNRIs[9,84,85].

Vasomotor symptoms

For vasomotor symptoms, HRT with oestrogen and progesterone can be offered to women with a uterus; oestrogen-only HRT can only be offered to women who have had a hysterectomy (or is without a uterus)[9]. SSRIs, SNRIs and clonidine should not be offered first line. The British Menopause Society provides guidance on prescribing clonidine[84].

Urogenital atrophy

Vaginal oestrogen should be offered in combination with systemic HRT to relieve symptoms; treatment should be continued for as long as required. Where systemic HRT is contraindicated, a specialist should be consulted and vaginal oestrogen should be considered. Counselling should be provided; adverse effects from vaginal oestrogen are very rare, any unscheduled vaginal bleeding should be reported to the GP. Women should also be informed that symptoms will return on cessation of therapy. For vaginal dryness, moisturisers and lubricants can be used alone or in addition to vaginal oestrogen[9].

Decreased libido

HRT should be considered for altered sexual function. If HRT alone is not effective, testosterone supplementation can be considered[9].

Compounded bioidentical hormones

The efficacy and safety of unregulated and compounded bioidentical hormones are unknown. Additionally, the quality, purity and constituents of the products are not always known[9].

Complementary therapies

There is some evidence that isoflavones or black cohosh may relieve vasomotor symptoms, but these hold risks. As with all herbal medicines, different preparations are available and may vary. In addition, safety is uncertain and interactions with other medicines have been reported[9]. Herbal medicines are not as highly regulated as prescription-only medicines (POM); there is often insufficient evidence on efficacy and safety (e.g. interactions). While women may choose to use complementary medicines alone or in conjunction with conventional therapy (e.g. HRT), pharmacists should explain risks, benefits and available or lack of evidence to ensure patient-informed management choices are made.

Although St John’s wort has some evidence of benefit for the relief of vasomotor symptoms, there are potentially serious drug interactions (e.g. tamoxifen, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants) and uncertainty regarding appropriate doses and the persistence of effects[9].

Cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT is a short-term, non-pharmacological strategy that can be used to manage anxiety, stress, depressed mood, hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbances and insomnia during perimenopause. CBT can be provided by general practitioners, counsellors, psychological wellbeing practitioners and trained nurses[83,86].

Contraception

Holistic management of perimenopause includes contraception — which will need to be continued for 2 years after menopause in women under 50 years and for 1 year in women over 50 years — owing to unpredictable ovulation[2,87].

The combined oral contraceptive pill can also be used to suppress the menstrual cycle in early perimenopause to manage hormonal fluctuations and/or the symptoms associated with higher oestrogen levels[2,84]. Combined oral contraceptive pills that contain oestradiol or oestradiol valerate (e.g. Zoely [Theramex]; Qlaira [Bayer]), when taken continuously (i.e. without medicine-free days), will address menorrhagia and mastalgia[2]. A levonorgestrel intrauterine device or progestogen-only contraceptive pill will provide contraceptive cover but will not address mastalgia; it does not sufficiently suppress the menstrual cycle[2]. During late perimenopause, women on a levonorgestrel intrauterine device with symptoms of oestrogen deficiency can be treated with additional oestrogen (e.g. patches)[2].

Hormone replacement therapy

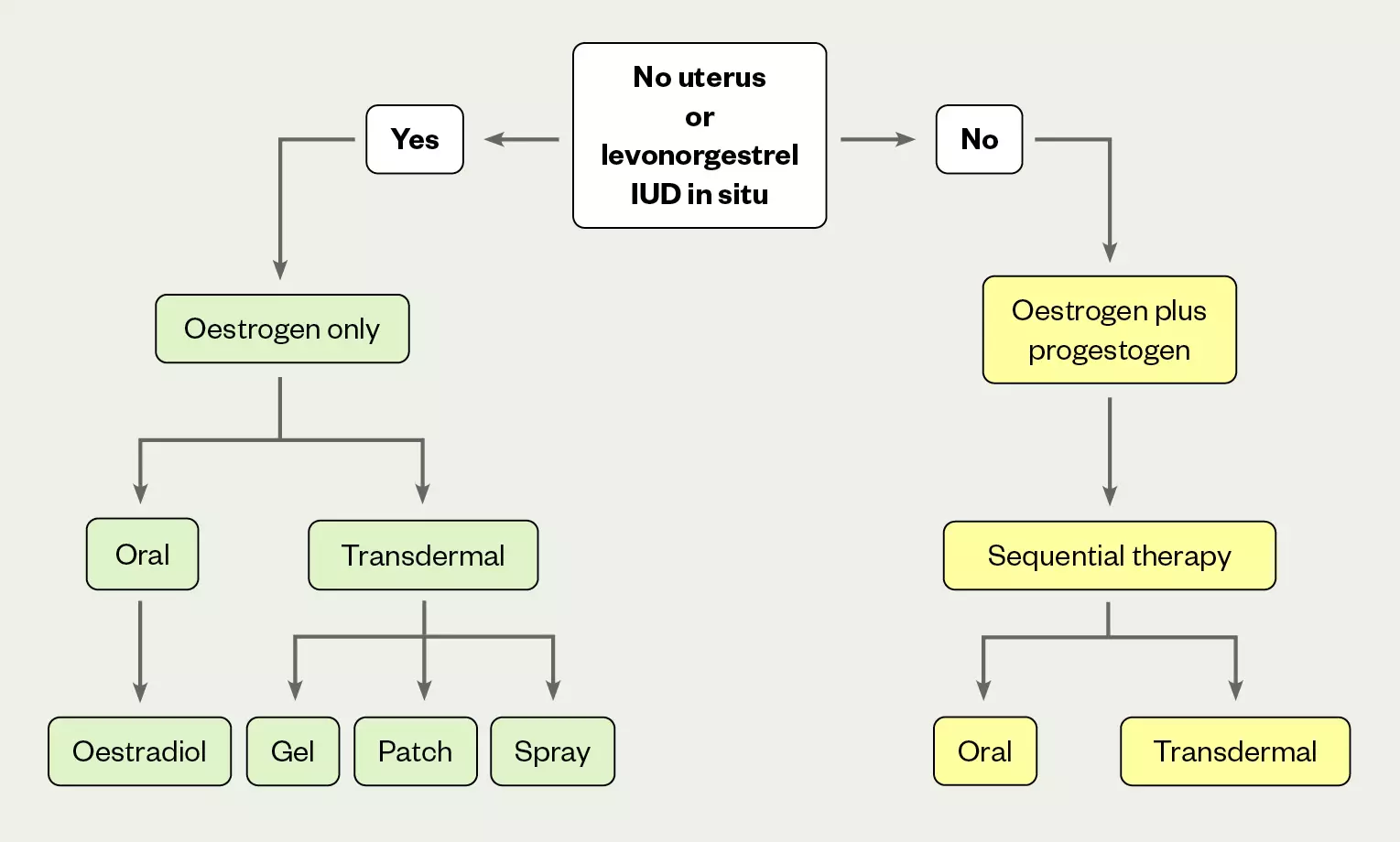

The most appropriate HRT will depend on the woman’s preference, the symptoms and stage of perimenopause (symptoms in early perimenopause are probably associated with oestrogen excess and in late perimenopause, symptoms are associated with oestrogen deficit), her contraception preferences, benefit and risk assessment, and whether she has a uterus (see Figure 1[1,2]).

Treatment (see Box 1 and Table 2[88]) should be reviewed for efficacy and tolerability at three months after commencement and yearly thereafter, unless earlier review is indicated and referral to a specialist is required. Indications for earlier review include inadequate treatment response and unacceptable or unexpected side effects. For example, unscheduled vaginal bleeding is a common side effect in the first three months of HRT, but should be investigated if it continues or occurs beyond the first three months. Further, referral to a specialist should be considered where HRT is contraindicated or there is uncertainty regarding the most appropriate treatment. Women with breast cancer or at high risk of breast cancer should be referred. Gradually ceasing HRT may limit rebound symptoms in the short term but does not appear to have any long-term benefits[9].

The above treatment options can include local oestrogen therapy

IUD: intrauterine device

For women in early perimenopause, oestrogen excess and fluctuation may be better managed by suppressing the cycle with continuous combined oral contraceptive; additional oestrogen only HRT can be used to manage symptoms as required

Box 1: Oestrogen-only hormone replacement therapy

Oral oestrogen only

Oestradiol 1mg or 2mg tablets (Elleste Solo [Mylan]; Zumenon [Mylan]; Progynova [Bayer])

OR

Transdermal oestrogen only

Oestradiol patches (micrograms per hour) twice weekly:

- Evorel (Theramex, 25, 50, 75 or 100);

- Estradot (Novartis, 25, 50, 75 or 100);

- Estraderm (Mera Labs Luxco II, 25, 50, 75 or 100);

- Femseven mono (Theramex, 50, 75 or 100);

- Progynova TS (Bayer, 50 or 100).

OR

Oestradiol gel (0.75mg per pump actuation)

- Oestrogel 1 pump actuation once daily = Evorel 25 twice weekly;

- Oestrogel 2 pump actuations once daily = Evorel 50 twice weekly.

OR

Oestradiol gel (0.5mg or 1.0mg per sachet)

- Sandrena (Orion Pharma) 0.5 mg gel 1 sachet once daily = Evorel 25 twice weekly;

- Sandrena 1 sachet once daily = Evorel 50 twice weekly.

OR

Oestradiol spray (1.53mg per spray)

- Lenzetto (Gedeon Richter) 3 sprays once daily = Evorel 50 twice weekly

See the BNF, SmPCs and BMS for further information on dosing, adverse effects, interactions, contraindications and dose titration

Box 2: Oestrogen plus sequential progestogen hormone replacement therapy

Oestradiol (1mg or 2mg) plus dydrogesterone 10mg oral tablets

- Femoston (Mylan, 1/10 or 2/10) = oestradiol (1mg or 2mg) daily on days 1 to 14, dydrogesterone 10 mg daily on days 15 to 28

OR

Oestradiol (1mg or 2mg) plus norethisterone 1mg oral tablets

- Novofem (Novo Nordisk) = oestradiol 1mg daily on days 1 to 16, norethisterone 1mg daily on days 17 to 28;

- Elleste Duet (Mylan, 1mg or 2mg) = oestradiol (1mg or 2mg) daily on days 1 to 16, norethisterone 1mg daily on days 17 to 28.

OR

Oestradiol (1mg or 2mg) tablets (Elleste Solo, Zumenon, Progynova)

PLUS

Progestogen (oral or intrauterine)

- Micronised progesterone 100mg oral capsules (Utrogestan [Besins Healthcare]) — 200mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Medroxyprogesterone 10mg oral tablets (Provera [Pfizer]) — 10mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Norethisterone 5mg oral tablets — 5mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Levonorgestrel 20 micrograms per 24 hours intrauterine device — effective for 5 years

OR

Transdermal oestrogen with sequential progestogen (norethisterone)

Oestradiol with norethisterone patches

- Evorel Sequi = Evorel 50 on days 1 to 14 of menstrual cycle plus Evorel Conti on days 15 to 28 of menstrual cycle

OR

Transdermal oestrogen plus progestogen (oral or intrauterine)

- Transdermal oestrogen only, equivalent to Evorel 50

PLUS

Oral or intrauterine progestogen

- Micronised progesterone 100mg oral capsules (Utrogestan) — 200mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Medroxyprogesterone 10mg oral tablets (Provera) — 10mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Norethisterone 5mg oral tablets — 5mg once daily for 12 days a month

OR

- Levonorgestrel 20 micrograms per 24 hours intrauterine device — effective for 5 years.

See the BNF, SmPCs and BMS for further information on dosing, adverse effects, interactions, contraindications and dose titration

Practice points

- Menopause is diagnosed 12 months after a woman’s last menstrual period, marking the end of that woman’s reproductive ability. The average age of menopause is 51 years.

- Perimenopause can affect women for more than a decade preceding menopause;

- Laboratory tests are not usually required to diagnose perimenopause;

- HRT does not provide contraceptive cover;

- Pharmacists need to know when to refer patients to other healthcare professionals;

- Women with a uterus on higher doses of oestrogen may require higher doses of progestogen for uterine protection;

- Estradiol 10 microgram vaginal tablets (GINA) was made available over the counter from September 2022 for vaginal atrophy in post-menopausal women aged 50 years and above. Pharmacists must be aware of vaginal-atrophy symptoms and treatment, and when to refer.

Counselling points

Pharmacists should be aware of and provide education on the following information, ensuring the information is commensurate with women’s literacy and health literacy:

- An absence of vasomotor symptoms does not exclude a diagnosis of perimenopause;

- Vasomotor symptoms are likely during late perimenopause and most likely during early post-menopause;

- Experience of vasomotor symptoms can be influenced by race and ethnicity;

- Symptoms not always or traditionally associated with perimenopause include anxiety, mood disorders, shorter menstrual cycle, increased duration of menstrual bleeding, arthralgia, headaches and migraine;

- A patient-centred, collaborative and evidence-based approach to symptom management is required;

- Benefits and risks of treatment should be assessed and explained to women with consideration to their literacy and health literacy;

- Pharmacists should always facilitate shared decision-making to allow for best treatment options.

Conclusion

Perimenopause can have a significant negative impact on a woman’s quality of life. A need for education and training of healthcare professionals in women’s health has been identified by the recent call for evidence in the first-ever government-led ‘Women’s Health Strategy for England’. Evidence-based medicine must be incorporated into a patient-centred, collaborative approach to management. Women must be supported to make informed decisions about their own treatment; self-determination is a fundamental human right. As one of the most accessible healthcare professionals in the UK, pharmacists must be able to recognise and help women manage symptoms of perimenopause, referring when required.

Useful resources

Declaration

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the position of Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia or Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

- 1HRT – Guide. British Menopause Society. 2020.https://thebms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/04-BMS-TfC-HRT-Guide-01-AUGUST2022-A.pdf (accessed Jan 2023).

- 2Perimenopause or Menopausal Transition. Australasian Menopause Society. 2017.https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/perimenopause (accessed Jan 2023).

- 3Santoro N. Perimenopause: From Research to Practice. Journal of Women’s Health. 2016;25:332–9. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5556

- 4What is Menopause? . National Institute of Aging. 2021.https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-menopause (accessed Jan 2023).

- 5Bacon JL. The Menopausal Transition. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2017;44:285–96. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.008

- 6Santoro N, Roeca C, Peters BA, et al. The Menopause Transition: Signs, Symptoms, and Management Options. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020;106:1–15. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa764

- 7Population and household estimates, England and Wales: Census 2021. Office for National Statistics. 2022.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/populationandhouseholdestimatesenglandandwales/census2021 (accessed Jan 2023).

- 8Our Vision for the Women’s Health Strategy for England. Department of Health and Social Care. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-vision-for-the-womens-health-strategy-for-england/our-vision-for-the-womens-health-strategy-for-england#ministerial-foreword (accessed Jan 2023).

- 9Menopause: Diagnosis and Management [NG23]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23/chapter/Context (accessed Jan 2023).

- 10Fuh J ‐L., Wang S ‐J., Lee S ‐J., et al. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12:53–61. doi:10.1023/a:1022074602928

- 11Talaulikar V. Menopause transition: Physiology and symptoms. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2022;81:3–7. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.03.003

- 12Hickey M, Hunter MS, Santoro N, et al. Normalising menopause. BMJ. 2022;:e069369. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069369

- 13Guthrie JR, Dennerstein L, Taffe JR, et al. Health care-seeking for menopausal problems. Climacteric. 2003;6:112–7. doi:10.1080/cmt.6.2.112.117

- 14Feingold K, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al. endotext. Published Online First: 5 August 2018.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/

- 15McLaughlin JE. Menstrual cycle. MSD Manual. 2022.https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-au/home/women-s-health-issues/biology-of-the-female-reproductive-system/menstrual-cycle (accessed Jan 2023).

- 16Kim S-M, Kim J-S. A Review of Mechanisms of Implantation. Dev Reprod. 2017;21:351–9. doi:10.12717/dr.2017.21.4.351

- 17Burger HG, Hale GE, Robertson DM, et al. A review of hormonal changes during the menopausal transition: focus on findings from the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project. Human Reproduction Update. 2007;13:559–65. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmm020

- 18DELAMATER L, SANTORO N. Management of the Perimenopause. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;61:419–32. doi:10.1097/grf.0000000000000389

- 19Peacock K, Ketvertis K. statpearls. Published Online First: 11 August 2022.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507826/

- 20Santoro N, Brown JR, Adel T, et al. Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1996;81:1495–501. doi:10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636357

- 21Shideler SE, DeVane GW, Kalra PS, et al. Ovarian-pituitary hormone interactions during the perimenopause. Maturitas. 1989;11:331–9. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(89)90029-7

- 22Weber MT, Maki PM, McDermott MP. Cognition and mood in perimenopause: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2014;142:90–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.06.001

- 23Hale GE, Hughes CL, Burger HG, et al. Atypical estradiol secretion and ovulation patterns caused by luteal out-of-phase (LOOP) events underlying irregular ovulatory menstrual cycles in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2009;16:50–9. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31817ee0c2

- 24Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10. Menopause. 2012;19:387–95. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40

- 25Menopause Transition: Effects on Women’s Economic Participation. Government Equalities Office. 2017.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/menopause-transition-effects-on-womens-economic-participation (accessed Jan 2023).

- 26Panay N, Palacios S, Davison S, et al. Women’s perception of the menopause transition: a multinational, prospective, community-based survey. GREM 2021;2:178–83. doi:10.53260/grem.212037

- 27Dennerstein L, Smith AMA, Morse C, et al. Menopausal symptoms in Australian women. Medical Journal of Australia. 1993;159:232–6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137821.x

- 28The British Menopause Society response to the Department of Health and Social Care’s call for evidence to help inform the development of the government’s Women’s Health Strategy. British Menopause Society. 2021.https://thebms.org.uk/2021/08/the-british-menopause-society-response-to-the-department-of-health-and-social-cares-call-for-evidence-to-help-inform-the-development-of-the-governments-womens-health-strateg (accessed Jan 2023).

- 29Paramsothy P, Harlow SD, Nan B, et al. Duration of the menopausal transition is longer in women with young age at onset: the multiethnic Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2017;24:142–9. doi:10.1097/gme.0000000000000736

- 30Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Symptoms Associated With Menopausal Transition and Reproductive Hormones in Midlife Women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;110:230–40. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000270153.59102.40

- 31Santoro N, Lasley B, McConnell D, et al. Body Size and Ethnicity Are Associated with Menstrual Cycle Alterations in Women in the Early Menopausal Transition: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) Daily Hormone Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89:2622–31. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031578

- 32Paramsothy P, Harlow S, Greendale G, et al. Bleeding patterns during the menopausal transition in the multi-ethnic Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN): a prospective cohort study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy. 2014;121:1564–73. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12768

- 33Ornello R, De Matteis E, Di Felice C, et al. Acute and Preventive Management of Migraine during Menstruation and Menopause. JCM. 2021;10:2263. doi:10.3390/jcm10112263

- 34Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17:954–76. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3

- 35Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine. Neurologic Clinics. 2019;37:631–49. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

- 36Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, et al. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21. doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0

- 37Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- 38Martin VT, Pavlovic J, Fanning KM, et al. Perimenopause and Menopause Are Associated With High Frequency Headache in Women With Migraine: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2016;56:292–305. doi:10.1111/head.12763

- 39Wang S-J, Fuh J-L, Lu S-R, et al. Migraine Prevalence During Menopausal Transition. Headache. 2003;43:470–8. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03092.x

- 40Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, et al. Characteristics of Menstrual and Nonmenstrual Attacks in Women with Menstrually Related Migraine Referred to Headache Centres. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:707–16. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00741.x

- 41MacGregor EA, Victor TW, Hu X, et al. Characteristics of Menstrual vs Nonmenstrual Migraine: A Post Hoc, Within-Woman Analysis of the Usual-Care Phase of a Nonrandomized Menstrual Migraine Clinical Trial. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2010;50:528–38. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01625.x

- 42Vetvik KG, Benth JŠ, MacGregor EA, et al. Menstrual versus non-menstrual attacks of migraine without aura in women with and without menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:1261–8. doi:10.1177/0333102415575723

- 43Güven B, Güven H, Çomoğlu S. Clinical characteristics of menstrually related and non-menstrual migraine. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117:671–6. doi:10.1007/s13760-017-0802-y

- 44Musial N, Ali Z, Grbevski J, et al. Perimenopause and First-Onset Mood Disorders: A Closer Look. FOC. 2021;19:330–7. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20200041

- 45Biegon A, McEwen B. Modulation by estradiol of serotonin receptors in brain. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:199–205. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.02-02-00199.1982

- 46Kugaya A, Epperson CN, Zoghbi S, et al. Increase in Prefrontal Cortex Serotonin2AReceptors Following Estrogen Treatment in Postmenopausal Women. AJP. 2003;160:1522–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1522

- 47Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM. Mood and Menopause: Findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) over 10 Years. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2011;38:609–25. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.011

- 48Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, et al. Risk for New Onset of Depression During the Menopausal Transition. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:385. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385

- 49Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Associations of Hormones and Menopausal Status With Depressed Mood in Women With No History of Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:375. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375

- 50Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y-F, et al. Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol. Med. 2011;41:1879–88. doi:10.1017/s003329171100016x

- 51Kravitz HM, Joffe H. Sleep During the Perimenopause: A SWAN Story. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2011;38:567–86. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2011.06.002

- 52Kravitz HM, Janssen I, Bromberger JT, et al. Sleep Trajectories Before and After the Final Menstrual Period in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Curr Sleep Medicine Rep. 2017;3:235–50. doi:10.1007/s40675-017-0084-1

- 53Woods N, Mitchell E, Adams C. Memory functioning among midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2000;7:257–65.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10914619

- 54Greendale GA, Huang M-H, Wight RG, et al. Effects of the menopause transition and hormone use on cognitive performance in midlife women. Neurology. 2009;72:1850–7. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3181a71193

- 55Magliano M. Menopausal arthralgia: Fact or fiction. Maturitas. 2010;67:29–33. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.009

- 56Delavar MA, Hajiahmadi M. Age at menopause and measuring symptoms at midlife in a community in Babol, Iran. Menopause. 2011;18:1213–8. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31821a7a3a

- 57Chen R, Yu Q, Xu K, et al. [Survey on characteristics of menopause of Chinese women with the age of 40-60 years at gynecological clinic from 14 hospitals]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2013;48:723–7.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24406126

- 58Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Sleep Symptoms During the Menopausal Transition and Early Postmenopause: Observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Sleep. 2010;33:539–49. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.4.539

- 59Pansini F, Albertazzi P, Bonaccorsi G, et al. The menopausal transition: a dynamic approach to the pathogenesis of neurovegetative complaints. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1994;57:103–9. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(94)90051-5

- 60Fuh J-L, Wang S-J, Lu S-R, et al. The kinmen women-health investigation (KIWI): a menopausal study of a population aged 40–54. Maturitas. 2001;39:117–24. doi:10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00193-1

- 61Matthews K, Wing R, Kuller L, et al. Influence of the perimenopause on cardiovascular risk factors and symptoms of middle-aged healthy women. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2349–55.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7944857

- 62Callan N, Mitchell E, Heitkemper M, et al. Constipation and diarrhea during the menopause transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2018;25:615–24. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001057

- 63Palomba S, Di C, Riccio E, et al. Ovarian function and gastrointestinal motor activity. Minerva Endocrinol 2011;36:295–310.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22322653

- 64Infantino M. The prevalence and pattern of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in perimenopausal and menopausal women. J Amer Acad Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20:266–72. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00316.x

- 65Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, et al. Prospectively Measured Levels of Serum Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, Estradiol, and the Dimeric Inhibins during the Menopausal Transition in a Population-Based Cohort of Women1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1999;84:4025–30. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.11.6158

- 66Kamm MA, Farthing MJ, Lennard-Jones JE, et al. Steroid hormone abnormalities in women with severe idiopathic constipation. Gut. 1991;32:80–4. doi:10.1136/gut.32.1.80

- 67Meleine M. Gender-related differences in irritable bowel syndrome: Potential mechanisms of sex hormones. WJG. 2014;20:6725. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6725

- 68Huang AJ, Grady D, Jacoby VL, et al. Persistent Hot Flushes in Older Postmenopausal Women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:840. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.8.840

- 69Bansal R, Aggarwal N. Menopausal hot flashes: A concise review. J Mid-life Health. 2019;10:6. doi:10.4103/jmh.jmh_7_19

- 70Sassarini J, Anderson RA. New pathways in the treatment for menopausal hot flushes. The Lancet. 2017;389:1775–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30886-3

- 71Freedman RR. Menopausal hot flashes: Mechanisms, endocrinology, treatment. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2014;142:115–20. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.08.010

- 72Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Sternfeld B, et al. Gains in Body Fat and Vasomotor Symptom Reporting Over the Menopausal Transition: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:766–74. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp203

- 73Kim H-K, Kang S-Y, Chung Y-J, et al. The Recent Review of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. J Menopausal Med. 2015;21:65. doi:10.6118/jmm.2015.21.2.65

- 74Avis NE, Colvin A, Karlamangla AS, et al. Change in sexual functioning over the menopausal transition: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2017;24:379–90. doi:10.1097/gme.0000000000000770

- 75Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause. Menopause. 2009;16:442–52. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0

- 76Hexsel D, Lacerda DA, Cavalcante AS, et al. Epidemiology of melasma in Brazilian patients: a multicenter study. International Journal of Dermatology. 2013;53:440–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05748.x

- 77MAEDA K, NAGANUMA M, FUKUDA M, et al. Effect of Pituitary and Ovarian Hormones on Human Melanocytes In Vitro. Pigment Cell Res. 1996;9:204–12. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.1996.tb00110.x

- 78Hale GE, Hitchcock CL, Williams LA, et al. Cyclicity of breast tenderness and night-time vasomotor symptoms in mid-life women: information collected using the Daily Perimenopause Diary. Climacteric. 2003;6:128–39. doi:10.1080/cmt.6.2.128.139

- 79Mishra GD, Kuh D. Health symptoms during midlife in relation to menopausal transition: British prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e402–e402. doi:10.1136/bmj.e402

- 80Mirmirani P. Hormones and clocks: do they disrupt the locks? Fluctuating estrogen levels during menopausal transition may influence clock genes and trigger chronic telogen effluvium. DOJ. 2016;22. doi:10.5070/d3225030937

- 81Borgonovi F, Pokropek A. The evolution of socio‐economic disparities in literacy skills from age 15 to age 27 in 20 countries. British Educational Res J. 2021;47:1560–86. doi:10.1002/berj.3738

- 82Hillman S, Shantikumar S, Ridha A, et al. Socioeconomic status and HRT prescribing: a study of practice-level data in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:e772–7. doi:10.3399/bjgp20x713045

- 83Table 1: Summary of HRT Risks and Benefits During Current Use and Current Use Plus Post-treatment from Age of Menopause up to Age 69 years, per 1000 Women with 5 Years or 10 Years Use of HRT. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. 2022.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d680409e5274a1711fbe65a/Table1.pdf (accessed Jan 2023).

- 84Prescribable alternatives to HRT. British Menopause Society. 2020.https://thebms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/02-BMS-TfC-Prescribable-alternatives-to-HRT-03A-JUNE2022.pdf (accessed Jan 2023).

- 85Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) for Menopausal Symptoms. British Menopause Society. 2019.https://thebms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/01-BMS-TfC-CBT-03-AUGUST2022.pdf (accessed Jan 2023).

- 86Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) for Menopausal Symptoms. Women’s Health Concern. 2020.https://www.womens-health-concern.org/2017/02/new-factsheet-cognitive-behaviour-therapy-cbt-menopausal-symptoms/ (accessed Jan 2023).

- 87Contraception for women aged over 40: What, When, and For How Long. Guidelines in practice. 2018.https://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/womens-health/contraception-for-women-aged-over-40-what-when-and-for-how-long/453901.article (accessed Jan 2023).

- 88HRT preparations and equivalent alternatives. British Menopause Society. 2022.https://thebms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/15-BMS-TfC-HRT-preparations-and-equivalent-alternatives-01D.pdf (accessed Jan 2023).