This content was published in 2003. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Identify gaps in your knowledge

- What advice could you give to a pregnant woman suffering from morning sickness?

- What product could you recommend to a pregnant woman for constipation?

- When should cases of pruritus in a pregnant woman be referred?

This article relates to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s core competency of “appropriate advice, referral or selection of treatment” (see “Medicines, ethics and practice — a guide for pharmacists”, number 26, July 2002, pp105–6). You should consider how it will be of value to your practice.

Although pregnancy is a normal, healthy state, changes that occur in an expectant mother’s body can produce a range of relatively minor but troublesome ailments. Many symptoms are a result of high levels of placental hormones in the mother’s circulation (mainly oestrogen and progesterone), but as pregnancy progresses the increasing size of the fetus produces physical stresses on the body that can also give rise to uncomfortable symptoms.

The role of pharmacists in responding to symptoms in pregnant women may be restricted compared with responding to symptoms in other people, because expectant mothers are more likely to speak to the health professional at their regular antenatal appointment about ailments. In addition, many of the over-the-counter (OTC) medicines usually appropriate for treating minor conditions are not licensed to be sold for use by pregnant women, although they are prescribable by a GP or obstetrician. Pregnant women are also generally anxious to avoid taking medicines.

However, pharmacists are the most easily accessible of health care professionals and may be asked for advice when symptoms develop between antenatal visits. Pharmacists are also likely to be asked by pregnant women and other health care professionals to advise on OTC medicines that are suitable for use in pregnancy. Even when there is no suitable OTC treatment, pharmacists can recommend other strategies for alleviating symptoms, and can help pregnant women make informed choices about their health. Pharmacists who respond to symptoms in pregnant women should remind them to let the GP or midwife know about these symptoms at their next antenatal appointment.

“Morning sickness”

Nausea in pregnancy is common; about 80 per cent of pregnant women suffer with it and around half of these also vomit. The condition frequently starts from about week five of gestation and in most women subsides after week 13, but it can sometimes return in the last three months. Symptoms are often more severe in women pregnant for the first time, those expecting more than one baby and those who have experienced nausea with oral contraceptives.

The term “morning sickness” is a misnomer because the nausea and vomiting can occur at any time of day, although it is commonly experienced on rising in the morning. The condition can be aggravated by certain foods or even the smell of cooking. The causes of morning sickness are unknown, but two main theories have been advanced:

- High levels of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) stimulate the ovaries to produce oestrogen and progesterone in early pregnancy, but levels decrease once the placenta is sufficiently developed to produce these hormones itself

- Low blood sugar on rising in the morning

There are no OTC medicines licensed for the treatment of morning sickness. Antihistamines considered effective and safe (eg, promethazine) and the antiemetics prochlorperazine and domperidone, although available OTC for other indications, cannot be sold for morning sickness. Doctors are able to prescribe these drugs but generally do so only as a last resort.

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is a non-prescription drug that has been used to treat morning sickness. It was widely prescribed in combination with the antihistamine dicyclomine, as Debendox, but this product was withdrawn in 1983 due to anecdotal reports (that were never proven) that dicyclomine was teratogenic. The little research that has looked at the efficacy of pyridoxine for morning sickness is inconclusive. In addition, high doses of pyridoxine have been associated with peripheral neuropathies and, in 1997, the United Kingdom government suggested that preparations providing doses of at least 50mg daily should be classified as prescription-only medicines, and those providing between 11 and 49mg daily as pharmacy medicines. However, no action has been taken and pyridoxine is still classified as a general sale list medicine. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has left it to the discretion of pharmacists to decide whether they treat the various strengths and dosages as POM, P or GSL. Dosages used for morning sickness range from 30 to 75mg daily. In the United States the maximum daily dose of pyridoxine without prescription has been set at 100mg.

There is some evidence of the efficacy of powdered ginger root, but the safety of ginger in pregnancy has not been established,1 and it is recommended that ginger should not be taken during pregnancy in amounts that greatly exceed those in food. Acupressure is another non-drug treatment with some evidence of efficacy.2 Bands (eg, Sea-Band) that apply continuous pressure to the P6 (Nei- Kuan) pressure point on each wrist are available and are unlikely to be harmful. (A later article in this series will discuss alternative therapies used in pregnancy.)

Some women find that making changes to their dietary or other daily habits can relieve morning sickness, and the measures set out in Panel 1 can be suggested. Pregnant women who experience severe and protracted vomiting (hyperemesis) may require admission to hospital for administration of antiemetics and to be rehydrated.

Panel 1: Advice for relieving nausea in pregnancy

- Eat small and frequent meals (four to six daily) to maintain blood sugar levels — do not wait until your stomach feels empty

- For nausea in the mornings, keep sweet biscuits by your bedside to eat when you first wake and after eating one or two, rest for about 20 minutes before getting up

- Eat a diet high in carbohydrates and proteins and low in fat

- Avoid spicy foods

- Drink plenty of water and fruit juices, but avoid alcohol and large quantities of tea, coffee or milk

- Suck barley sugar, boiled sweets or peppermints when travelling

- If nausea is worse late in the day, prepare the main meal in the morning

- Ask someone to take over chores that heighten nausea, such as cooking or feeding the dog or cat

- Some women find that drinking ginger or peppermint tea helps

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Gastro-oesophageal reflux or “heartburn” is suffered by around two-thirds of pregnant women in the later stages of pregnancy. Symptoms can be described as burning discomfort or pain in the epigastrium or retrosternal region and are caused by the reflux of gastric juice into the lower oesophagus. This is due partly to upward pressure on the stomach from the growing foetus and partly to incompetence of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), caused by raised progesterone levels reducing smooth muscle tone. Symptoms are worse when lying down.

Antacid preparations are licensed for OTC use in pregnancy. Calcium carbonate, which has the greatest neutralising capacity, or a combination of aluminium and magnesium salts, which are relatively insoluble and therefore persist for longer in the stomach, are probably the compounds of choice. Aluminium salts tend to cause constipation and magnesium salts tend to cause diarrhoea so combining the two can balance these effects. Products with a high sodium content should be avoided, because they can increase blood pressure (the British National Formulary indicates preparations with a low sodium content), as should products containing bismuth (bismuth is potentially neurotoxic). Antacid preparations containing alginates are often recommended for treatment of reflux because they precipitate out in the acid medium of the stomach to form a sponge-like “raft”. This is given buoyancy by carbon dioxide gas bubbles trapped in its matrix, generated from the reaction between stomach acid and sodium or potassium carbonate in the preparation. The theory is that the raft floats on top of the stomach contents and is pushed towards the LOS by peristaltic contractions, forming a plug that prevents regurgitation. Opinion as to any advantage over simple antacid preparations appears to be divided. Histamine H2-antagonists (eg, ranitidine, famotidine) are not licensed for use in pregnant women.

For non-drug management strategies, see Panel 2. Giving advice on heartburn is also an opportunity to check a woman’s smoking status.

Panel 2: Advice for minimising heartburn

- Eat frequent, small meals to avoid distending the stomach

- Do not eat late in the day — give yourself at least three hours after a meal before going to bed

- Use extra pillows in bed to sleep in a raised position.

- Avoid alcohol, coffee and chocolate — all act to relax the lower oesophageal sphincter

Headache and backache

Headaches are common in pregnant women, due to intracranial vascular changes mediated by progesterone and oestrogen. Conversely, migraine attacks often improve during pregnancy. Headaches tend to be worst during the second trimester but can persist throughout pregnancy.

Backache is another common complaint, caused by strain on the muscles of the back as the uterus enlarges and grows forward. In the last three months, the hormone relaxin softens the muscles and ligaments in readiness for labour, making them more able to stretch, but this can make them ache. Weight gain can also put stress on joints.

Treatment for pain is more or less restricted to paracetamol, which is generally regarded as safe to use throughout pregnancy. There is insufficient evidence of the safety of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in the early stages of pregnancy to justify their use. Both aspirin and ibuprofen should be avoided, because they can delay the onset of labour and can adversely effect late-stage developments in the fetus. Aspirin also increases the risk of haemorrhage in labour. Codeine and dihydrocodeine are co-formulated with paracetamol in several OTC analgesics. There is no evidence of teratogenic risk with these preparations, but they may depress respiration in newborn babies if taken near term. A massage can help alleviate headache. Advice that can be offered for minimising back pain is shown in Panel 3.

Panel 3: Advice for minimising back pain

- Do not stand or sit in the same position for too long

- Rest when pain is severe, sitting or lying with the legs raised

- Support the back with a pillow when sitting

- Wear flat shoes

- When picking up anything heavy (eg, children) take the strain on the legs, not the back

- Try gentle stretching to relax tight muscles

- Soak in a warm bath

Constipation

Constipation is most common in the later stages of pregnancy. Intestinal motility is reduced by raised progesterone levels, and the effect may be exacerbated by dietary changes and reduced physical activity. Iron therapy (discussed in the next article in this series) may also be a contributory factor.

The first treatment option should be to increase fluid intake and the amount of fibre in the diet. If this approach is unsuccessful, bulkforming laxatives (eg, ispaghula husk) or lactulose could be tried. Bulk-forming laxatives are not absorbed, but may cause abdominal distension and therefore discomfort. Lactulose is a non-absorbed disaccharide that increases intestinal bulk by attracting water into the colon by osmosis. Both have a relatively slow action, taking up to 48 hours to work, but are generally thought to be safe to use in pregnancy. The surfactant stool softening agent, docusate, is also considered safe. The stimulant laxative, senna, is not teratogenic and one or two doses can be tried if “gentler” laxatives fail. Senna probably should not be used in the later stages of pregnancy because theoretically, it can cause uterine contractions. However, evidence of this is scarce.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids, from straining at stool, are a possible complication of constipation. Treatment and prevention of recurrence of constipation is the best strategy. In mild cases a bland haemorrhoidal cream or ointment, such as Anusol or Preparation H, can be tried.

The former contains bismuth oxide which, although potentially neurotoxic, is unlikely to be absorbed through the rectal mucosa and cause harm. Also, the manufacturer states that there is no epidemiological evidence of adverse effects to the mother or fetus caused by Anusol. Alternatively, an ice pack can be applied.

Candidiasis (thrush)

Vaginal candidiasis occurs between two and 10 times more frequently in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women. During pregnancy, candidal growth is promoted because the vagina is rich in glycogen. Imidazole antifungals available without prescription are effective, but are not licensed to be sold for use by pregnant women. Pharmacists therefore have no alternative but to refer patients to a doctor. However, pharmacists can reassure an expectant mother that thrush will not harm her baby’s development (although it can be passed to the baby as it passes through the birth canal).

Varicose veins, oedema and muscle cramps

Varicose veins affect between 10 and 20 per cent of pregnant women. Up to 80 per cent can suffer with leg oedema, and about one third experience cramps in calf muscles in late pregnancy. Support hosiery is usually recommended for treatment of varicose veins. To relieve oedema, sufferers should spend as much time as possible resting, with their legs elevated. Wearing tight clothes should be avoided.

An increased intake of calcium and potassium has been recommended to reduce the incidence of leg cramps, although there is no evidence of effectiveness. Avoiding high heeled shoes, and putting a pillow at the foot of the bed to prevent stretching the foot forward from the ankle while lying on the back, which often triggers cramp, are probably more effective measures. Massage and stretching of the affected muscles during an attack are the only form of relief that can be recommended.

Pruritis

Pregnant women can suffer from a variety of itching conditions, including those unrelated to pregnancy, but the main itching condition specifically associated with pregnancy is pruritus gravidarum, a generalised mild itching without rash that affects up to 20 per cent of pregnant women. It can occur from the third month onwards and is thought to be due to oestrogen-induced cholestasis. The itch may respond to a soothing preparation such as oily calamine lotion. Prolonged and severe itching, particularly if associated with jaundice, are indications of more severe cholestasis that must be investigated.

There is a variety of itching conditions characterised by papular (small, well-defined elevated spots) rashes, but any woman presenting with one should be referred because some conditions are potentially serious, and it is not easy to distinguish between a serious and non-serious condition. All would, in any case, need to be treated with prescription medicines or OTC medicines which are not licensed for use in pregnant women.

Stretch marks and hyperpigmentation

Hormonal changes in pregnancy cause changes in skin coloration. Hyperpigmentation occurs due to increased levels of melanocytestimulating hormone, while oestrogen makes veins more noticeable. Changes that can occur include melasma (brown, clearly defined patches) on the face, darkening of the nipples, areola and external genitalia, and linea nigra, a dark line extending down the abdomen from the navel. All of these normally fade within in few weeks following delivery.

Stretch marks are caused by the overstretching of elastic tissue in the skin as the abdomen and breasts enlarge and the replacement of collagen by scar tissue. They appear as red bands or lines during pregnancy, which usually fade afterwards to a white or silvery colour but may never disappear completely. Exercise during pregnancy is said to help prevent stretch marks. Several proprietary products for massaging on to affected sites are available (constituents include vitamin E, cocoa butter, collagen and elastin) but there is little published research on the efficacy of anti-stretch mark products, and none on any currently marketed in the UK. After pregnancy, tretinoin has been used by some dermatologists to reduce scarring in severe cases.

Coughs and colds

Most ingredients of OTC remedies for coughs and colds are not contraindicated in pregnancy. However, most pregnant women prefer to avoid medication if at all possible and it is best to recommend products that are known not to pose any risk.

For dry coughs and sore throats, sucking non-medicated pastilles or even boiled sweets may be as effective as local anaesthetic lozenges and cough suppressants by keeping the inflamed tissue of the pharynx moistened with saliva, thereby reducing the soreness that causes reflex coughing. Simple linctus can also be recommended for its short-term soothing effect. In chesty coughs, steam inhalations can help to liquefy and expectorate pharyngeal mucus. Products containing systemic sympathomimetic decongestants should be avoided because of the risk of raising blood pressure. Inhaled volatile oils-based decongestants also provide relief and are generally considered to be safe in pregnancy.

Action: practice points

- Find out what information is available to support the safety or otherwise of using prochlorperazine in pregnancy.

- Next time you respond to symptoms in a pregnant woman, take time afterwards to reflect on the advice you gave and how it could be improved. Remind yourself of the information related to use in pregnancy printed in the patient information leaflet of the product you recommended.

- Discuss with a colleague whether or not you think pregnant women could be advised to use certain products. (eg, although manufacturers advise against use of sympathomimetic nasal drops, because they cause vasoconstriction, what is the real risk of systemic absorption?)

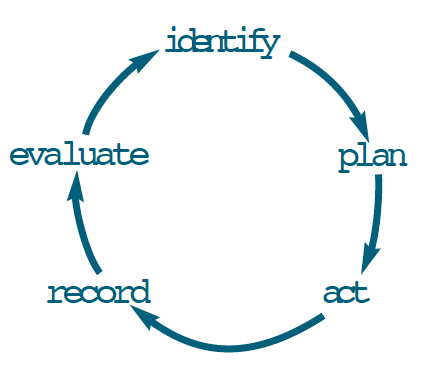

Evaluate

How could your learning have been more effective? What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

References

- Backon J. Ginger in preventing nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a caveat due to its thromboxane synthetase activity and effect on testosterone binding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Rep Bio 1991;42:163.

- Steele NM, French J, Gatherer-Boyles J, Newman S, Leclaire S. Effect of acupressure by Sea-Bands on nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2001;30:61–70.

Further reading

- Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Sumner JY. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation (6th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002.

- Enkin M, Keirse M, Neilson J, Crowther C, Hodnett E, Hofmeyr J. A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth (3rd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp95–107.

- Lee A. Common problems in pregnancy. In: Lee A, Inch S, Finnigan D, editors. Therapeutics in pregnancy and lactation. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2000.

- Avery AJ, Carr S. Treatment of common minor and self-limiting conditions. In: Rubin P, editor. Prescribing in pregnancy (3rd ed). London: BMJ Books; 2000. pp15–28.

- Nathan A. Non-prescription medicines (2nd ed). London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2002.