Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are rare but severe mucocutaneous conditions, which are often adverse effects of newly started pharmacotherapy. Incidence of SJS/TEN

in the UK is estimated at 1–2 cases per million person-years[1]

, although more recent data suggest that the true UK incidence may be as high as 5.76 cases per million person-years[2]

. SJS and TEN are described as phenotypes of the same condition (the set of observable characteristics of an individual resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the environment) and differentiated by the area of skin affected. SJS, the milder form, affects up to 10% of body surface area (BSA), overlap of SJS/TEN affects 10–30% of BSA, while TEN generally affects more than 30% of BSA.

Although these conditions are rare, they can be fatal in around 10% of cases for SJS and 30% of cases for TEN[3]

, which necessitates urgent management by a range of specialists in secondary care. SJS and TEN are also associated with long-term sequelae affecting quality of life[4]

. Therefore, pharmacists across all sectors should be aware of these conditions and be able to advise on pharmacotherapy, optimise medicines and provide patient-centred care.

This article aims to give an overview of SJS and TEN, and provide guidance and practical information for pharmacists who are involved in the care of patients with these conditions.

Aetiology

Current evidence suggests that around 85% of SJS/TEN cases are caused by medicine that is initiated in the preceding eight weeks of disease presentation, with the remaining cases being of unknown aetiology or, more uncommonly, Mycoplasma pneumoniae or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections[3],[5],[6]

.

Research has identified several drugs that carry a higher risk of precipitating SJS and TEN than other medicines (see Table 1). The ALDEN prediction score has been used to determine the relative risk of each medicine precipitating SJS/TEN and suggests that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and phenobarbital carry the greatest risk, followed by other anticonvulsants, other antimicrobials and allopurinol[3],[6],[7],[8]

. However, the growing evidence base also suggests anticonvulsants may carry an equal or greater risk of causing SJS/TEN compared with antimicrobials, with trimethoprim alone potentially posing the most significant risk across all antimicrobials[9],[10]

.

Some patient groups may be considered at increased risk of SJS/TEN owing to the medicines they are prescribed, including those with epilepsy who are newly started on treatment; those with gout who are newly started on allopurinol; and those with HIV, cancer or pneumonia who are more likely to receive antimicrobial therapy[2]

. HIV-positive individuals may also be at increased risk of SJS/TEN owing to the HIV disease process and the immunological changes this brings[11]

.

| Medicine group | Strongly associated | Less strongly associated | Weakly associated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobials |

|

|

|

| Anticonvulsants |

| — |

|

| Analgesia |

|

|

|

| Antidepressants | — |

|

|

| Others |

|

|

|

| This list is not exhaustive and individual cases for other medicines may exist. Sources: J Invest Dermatol | |||

Determining absolute risk from medicines is difficult owing to the infrequency of SJS/TEN and identification of the causative agent is often complicated by polypharmacy, acute medicines and self-medication. For example, paracetamol and ibuprofen are commonly taken during the prodromal phase for fever and malaise, while antibiotics may be prescribed during the early stages when SJS/TEN can be mistaken for an infection, all of which may be falsely identified as the cause[3],[5]

.

The initial signs of SJS/TEN generally manifest within 5–28 days of initiating the offending drug, but the risk may persist for three months after initiating therapy[2]

. Patients who have previously experienced a severe cutaneous adverse reaction to a medicine may develop SJS/TEN much more rapidly on rechallenge to the same drug or structurally related drugs[7],[12]

. Therefore, it is imperative that pharmacists assess these patients early and undertake a thorough medicines reconciliation to identify all potential causative agents within the past three months. Medication history should be recorded with a timeline, taking consideration of pharmacokinetics for the individual patient, to determine each drug’s likelihood of being a cause. This timeline must include prescription medicines, over-the-counter (OTC) products, herbal and complementary therapies, and exposure to recreational drugs and industrial chemicals (see Box 1)[12]

.

Box 1: Considerations when performing a medication history for patients with suspected Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Pharmacists should follow the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Medication History Quick Reference Guide to perform a thorough medication history. In addition, the following points are particularly important to identify causative agents in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis:

- Obtain a history over the past three months as a minimum;

- Record history as a timeline in relation to onset of symptoms;

- Identify or exclude the following:

- Over-the-counter medicines, medicines bought online and medicines obtained from friends/family;

- Herbal and complementary therapies;

- Recreational and ‘party’ drugs;

- Chemical exposure (industrial or occupational);

- Supplements (health or sport);

- Contraception;

- Changes in brand/manufacturer;

- Understand how the patient uses these products:

- Are they still taking the medicine? If not, when and why did they stop?;

- Did they start taking the medicine later than intended/prescribed?;

- Were any doses changed? If so, when?;

- Are they taking a different dose than prescribed/labelled?;

- How and when did they take acute medicine courses?;

- Explore previous allergies and intolerances — particularly cutaneous drug reactions.

Pathophysiology

An in-depth review of the pathophysiology and diagnosis of SJS and TEN is outside the scope of this article but readers who wish to extend their knowledge are encouraged to read the articles by Creamer et al.

[12]

, and Hoetzenecker et al.[13]

.

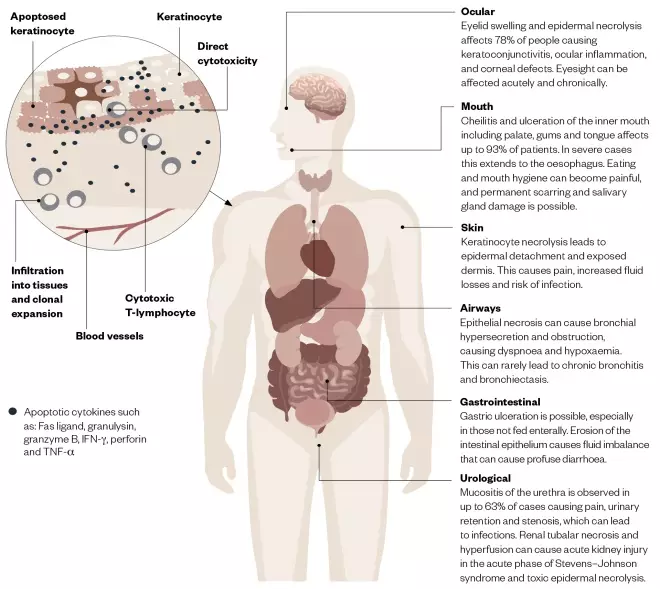

The pathophysiology of SJS and TEN involves cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-driven keratinocyte apoptosis, which affects many mucocutaneous regions of the body[14],[15]

. Figure 1 gives a brief overview of the complex biological processes and systems implicated in SJS/TEN.

Figure 1: Overview of the pathophysiology and clinical signs and symptoms of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Source: JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

An initial prodrome of fever, malaise and respiratory tract symptoms occurs around one to three days before visible skin lesions appear[1],[16]

. Given these non-specific, influenza-like symptoms, patients are unlikely to seek healthcare advice until epidermal involvement occurs. Ocular signs and symptoms (e.g. eyelid swelling) may also manifest before epidermal involvement becomes noticeable.

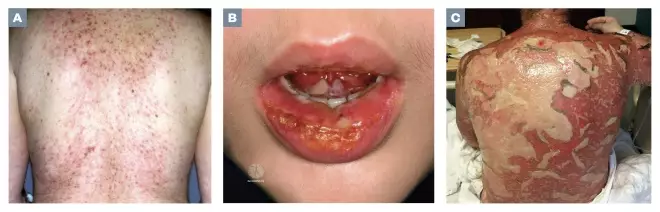

The first notable symptom may be skin becoming tender to touch, which should act as a red flag for all healthcare professionals. Dark-red flat lesions may initially appear on the upper torso, upper limbs and face, which spread across the trunk and lower limbs including the palms and soles (see Figure 2; A and B). Rarely, the initial lesions may present as diffuse erythema.

The lesions are often painful[17]

, with minimal lateral force causing detachment of the epidermis that slides across the dermis (Nikolsky’s sign)[1]

. Lesions spread and coalesce; this is followed by detachment of the epidermis two to six days after onset (see Figure 2; C). Exposed dermis exudes serous fluid, which increases insensible losses and can affect drug pharmacokinetics.

Figure 2: Photoguide

Source: ISM / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY / DermNet NZ / Wikimedia

Photo (A) is early target lesions; (B) shows lesions affecting the lips and oral mucosa; and (c) shows denuded skin with exposed dermis and gradual re-epithelialisation

Involvement of other mucocutaneous membranes — such as the oral and gastrointestinal mucosa, respiratory tract, genitalia, urinary tract (including kidneys), eyes and ocular structures — is common. Ocular involvement can initially present as swelling of the eyelids or conjunctiva (chemosis). Keratoconjunctivitis can rapidly progress to corneal and conjunctival epithelial defects, secondary corneal ulcers and eyelid skin eruptions. Severe cases develop subconjunctival fibrosis with cicatricial sequelae, including symblepharon, fornix shortening, corneal scarring and loss of vision. Common long-term sequelae involve dry eyes, trichiasis and lid malposition, leading to corneal ulceration and scarring, which results in altered vision and, on occasion, significant loss of vision. Necrosis of the renal tubules, along with altered fluid balance, can precipitate acute kidney injury and thus impact on pharmacotherapy. While liver enzymes can become deranged, liver failure is rare and generally does not impact on the management of these patients[18],[19]

.

Management

There is no recommended active treatment for SJS/TEN and management involves intense supportive measures, determined on a patient-by-patient basis (see Box 2), to promote tissue regeneration and prevent sequelae[19]

. The management options given here align with the 2016 UK guidelines for the management of SJS/TEN in adults[12]

. Readers are encouraged to read these and any local guidelines that may be available.

Box 2: Example of pharmacotherapy for patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

This is a summary of the initial pharmaceutical care, which will differ for each individual patient and will change as the patient’s condition progresses.

Skin care

- Irrigate eroded and intact skin with warmed sterile water, 0.9% sodium chloride or chlorhexidine;

- Apply a 50:50 mixture of liquid paraffin and white soft paraffin frequently to the whole epidermis. A spray formulation (e.g. Emollin®; CD Medical) can minimise handling of the vulnerable skin;

- Apply primary non-adherent dressings, with secondary foam or burn dressing to absorb exudate.

Eye care

Eye drops and ointments must be preservative-free and applied throughout the day and night.

- Lubricant eye drops (e.g. hyaluronate 0.2%) every 1–2 hours;

- Antibiotic eye drops (e.g. chloramphenicol 0.5% or levofloxacin 5mg/mL) every 6 hours;

- Steroid eye drops (e.g. dexamethasone 0.1%) every 2 hours.

Mouth care

- White soft paraffin applied to lips every 2 hours;

- Protective mouthwash (e.g. Gelclair; Alliance Pharmaceuticals) every 6–8 hours;

- Analgesic mouthwash or spray, such as benzydamine 0.15% every 2–3 hours;

- Antiseptic mouthwash (e.g. 0.2% chlorhexidine) twice daily.

Urological care

- Non-adherent dressing (e.g. Mepitel®; Mölnlycke) used on eroded areas of the vulva and vagina;

- White soft paraffin ointment applied to urogenital skin and mucosae every 4 hours;

- Potent topical corticosteroid ointment (e.g. betamethasone valerate 0.1%) applied once daily to involved, non-eroded, urological surfaces.

Fluid and electrolyte management

- Crystalloid fluid equivalent to 2mL/kg/% body surface area (BSA) epidermal detachment per day for the first 48 hours. Then fluid management to achieve urine output greater than 1mL/kg/hour;

- 5% human albumin solution at 1mL/kg/% BSA epidermal detachment;

- All electrolytes should be monitored and replaced frequently.

Nutritional support

Ideally given orally, otherwise enteral feeding tubes or parenteral feeding should be considered.

- Energy intake of 20–25kcal/kg during early catabolic stage;

- Energy intake of 25–30kcal/kg during the anabolic recovery stage;

- Protein intake of at least 1.5–2g/kg/day;

- Micronutrient supplementation (e.g. Forceval®; Alliance Pharmaceuticals) may aid wound healing.

Analgesia

- Simple analgesia (e.g. paracetamol and a weak opioid) to control pain at rest;

- Strong opioids for moderate-to-severe pain;

- Additional analgesia may be required for procedures and interventions;

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided.

Other supportive therapies

- Anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated;

- Proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed for those given parenteral nutrition.

Management of infection

- Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis is not required;

- Regular swabs of the skin, lips and oropharynx should be taken to monitor colonisation;

- Acute infections should be managed in line with microbiology results or empirically as per the source and swab results.

Immunomodulation

- There are no recommended immunomodulatory therapies, but the following may be used on a patient-by-patient basis:

- Ciclosporin;

- Corticosteroids;

- Intravenous immunoglobulins;

- Thalidomide should not be used.

The most important aspects of initial management is to stop the causative drug (or drugs) and withhold any non-essential medicines[1],[12]

. Epidermal loss and exposed dermis can increase risk of infections, and results in thermoregulatory dysfunction and increased energy expenditure. Therefore, patients should be barrier-nursed in a single room where the temperature can be increased to around 30–32o C to reduce energy expenditure and support recovery[12],[20]

.

SJS/TEN is a complex medical emergency and patients should receive urgent and regular input from a range of specialists, including dermatologists, ophthalmologists, intensivists, dietitians and pharmacists. The SCORTEN prediction score (a severity of illness scale; see Box 3; Table 2) should be calculated within 24 hours of admission to guide the level of care and predict mortality.

Box 3: The SCORTEN prediction score

The patient should be assessed within 24 hours of admission to see whether they have any of the following SCORTEN parameters, and their score should be calculated. The total number of paramets met will inform their predicted mortality score (see Table 2).

- Age over 40 years;

- Presence of malignancy;

- Heart rate over 120 beats per minute;

- Epidermal detachment greater than 10% body surface area at admission;

- Serum urea greater than 10mmol/L;

- Serum glucose greater than 14mmol/L;

- Serum bicarbonate less than 20mmol/L.

| Parameters met | Predicted mortality |

|---|---|

| Source: J Invest Dermatol [74] | |

| 0 | 1% |

| 1 | 4% |

| 2 | 12% |

| 3 | 32% |

| 4 | 62% |

| 5 | 85% |

| 6 | 95% |

| 7 | 99% |

Dermatological management

Healing of the skin occurs gradually over a period of weeks, with complete re-epithelialisation observed within 16–30 days[21]

. Careful handling of the skin is essential as the necrotic epidermis is prone to detachment[22]

. Eroded and intact skin should be regularly cleansed by irrigating gently with warmed sterile water, 0.9% sodium chloride or an antimicrobial such as chlorhexidine. A conservative wound management approach should be initiated with detached epidermis left in situ to act as a biological dressing[12]

.

In some cases of TEN, factors such as local sepsis or delayed healing may require surgical intervention[12]

. This involves the removal of necrotic epidermis and wound cleansing using a topical antimicrobial agent (e.g. betadine or chlorhexidine) under general anaesthetic, and may involve debridement then closure with Biobrane® (Mylan), allograft or xenograft skin[23],[24]

.

To reduce fluid, protein and temperature loss, and restore a barrier against infection, a greasy emollient such as 50% white soft paraffin with 50% liquid paraffin should be frequently applied to the whole epidermis, including denuded areas[25]

. A spray formulation such as Emollin® (CD Medical) may help minimise handling of the vulnerable skin[26]

. Large volumes of emollients are required during the acute phase and pharmacists should ensure adequate supplies are made available.

The use of an appropriate dressing can reduce losses and limit microbial colonisation of denuded skin. Suitable non-adherent dressings include Mepitel® (Molnlycke) or Telfa™ (H&R Healthcare), with secondary foam or burn dressing such as Exu-Dry® (Smith & Nephew) used to absorb exudate[12]

.

Exposed dermis with necrotic debris provides a substrate for microbial colonisation, which may lead to infection and sepsis; the most common cause of death in SJS/TEN[4]

. It is suggested that the exposed dermis can be swabbed every two to three days to monitor which organisms are present and predominating[12]

. Topical antimicrobial agents, guided by local microbiological advice, are recommended for sloughy areas of skin (dead tissue, usually creal or yellow in colour) and can be supplemented with silver-containing products or dressings[12]

. Indiscriminate use of systemic antibiotics can increase skin colonisation, particularly with Candida, so should only be used where there is a clinical suspicion of infection[4]

. Antimicrobial choice should be guided by swab results or treated empirically under microbiologist advice because broad-spectrum agents may be required to cover Gram-positive organisms commonly found within the skin microbiota, as well as Gram-negative organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, at a later stage of the condition[4]

.

Ophthalmological management

Prompt and intensive treatment with daily follow-up by an ophthalmologist is essential to reduce the risk of acute and chronic complications[12],[27]

. Topical treatment involves intensive one- to two-hourly preservative-free lubricant eye drops (e.g. hyaluronate 0.2%) throughout the day and night, prophylactic topical antibiotic eye drops (e.g. chloramphenicol 0.5% or a quinolone such as levofloxacin 5mg/mL) four times daily, and steroid eye drops (e.g. dexamethasone 0.1%) every two hours. Topical medication must be preservative-free as preservatives can cause damage to the already fragile ocular surface[28],[29]

. Ocular ointments are generally preservative-free, provide good long-term lubrication and can provide sustained drug delivery[30]

, which is useful for reducing the frequency of administration, particularly during sleeping hours.

In cases of corneal ulceration, topical antibiotic treatment should be altered according to clinical findings and microbiological results, which may be intensified up to hourly throughout the day and night. A combination of preservative-free quinolone and second-generation cephalosporin (e.g. cefuroxime 5%) may be required and the frequency of topical steroids may need to be adjusted.

In severe SJS/TEN cases, the use of amniotic membrane transplants (AMT) is beneficial owing to its anti-inflammatory and ocular surface-enhancing properties[31]

. AMT helps re-epithelialise the corneal and conjunctival surface and its use, along with fornix spacers, can help prevent symblepharon formation[32]

. However, patients’ vision will be severely impaired with AMT in situ, which impacts on engagement with daily activities, care and quality of life. The AMT usually disintegrates after one week, so repeated procedures might be required. Regardless of repeated AMT, long-term quality of life and independence may still be compromised.

Oral and respiratory management

All patients must have daily oral examinations. Oral lesions are intensely painful and limit oral intake, so patients may need supplemental intravenous fluids and nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding. White soft paraffin should be applied to lips every two hours alongside mucoprotectant mouthwash every eight hours. Benzydamine 0.15% as a spray or mouth rinse every two to three hours can provide analgesia. Systemic analgesia should also be offered to reduce pain from oral lesions. Secondary infection is common; regular surveillance swabs should be taken from the lips and oropharynx, and the use of antiseptic mouthwash (e.g. 0.2% chlorhexidine, diluted to 50% if necessary owing to pain) to reduce bacterial colonisation should be considered. Candidal infection should be treated with nystatin suspension[12]

.

Patients with SJS/TEN presenting with hypoxia, respiratory distress or haemoptysis need urgent assessment by critical care as many will require mechanical ventilation. Risk for mechanical ventilation increases as affected BSA increases and it is highest in patients with BSA detachment greater than 30%. Mortality rates of up to 70% are reported in those requiring ventilation and transfer to a specialist burns critical care unit should be strongly considered as bronchial epithelial sloughing can block airways and emergency therapeutic bronchoscopy may be needed[33]

. Bronchial lesions and mechanical ventilation also increases the risk of pneumonia, so antimicrobial therapy with broad-spectrum agents is often necessary[34],[35]

.

Urological management

Urogenital erosions may persist for several weeks and any resultant scarring can lead to permanent urinary or sexual dysfunction[36],[37]

. Daily urogenital review is recommended during the acute phase with the aim to reduce pain and prevent scarring[12]

.

All patients should be catheterised to prevent strictures in the urethra, which also allows accurate monitoring of fluid balance. A non-adherent dressing, such as Mepitel, should be used on eroded areas of the vulva and vagina to reduce pain and prevent adhesions. Apply white soft paraffin ointment to the urogenital skin and mucosae every four hours during the acute phase[12]

.

Topical corticosteroids used during the acute phase may also prevent long-term scarring[38],[39]

. A potent topical corticosteroid ointment (e.g. betamethasone valerate 0.1%) should be applied once daily to the involved, but non-eroded, urological surfaces[12]

.

Fluid and nutritional management

Large insensible fluid losses must be anticipated and aggressively managed to prevent hypovolemia and end-organ hypoperfusion. The Parkland formula, used in burns[40]

, may risk hypervolemia and the worsening of lung and intestinal injuries owing to oedema[12]

. The suggested regimen is crystalloid fluids equivalent to 2mL/kg/%BSA epidermal detachment per day for the first 48 hours[41]

with subsequent fluid management achieving urine output greater than 1mL/kg/hour and normalisation of base excess (risk of alkalosis) and lactate. SJS/TEN can precipitate hypoalbuminaemia, which has been associated with increased mortality[42]

, and, therefore, albumin replacement with 5% human albumin solution should be considered at a dose of 1mL/kg/%BSA epidermal detachment[20]

. A blood transfusion may also be necessary to counteract bleeding tendencies and restore lost haemoglobin.

SJS/TEN is accompanied by a hypermetabolic response with exudate losses; thus nutritional requirements are raised[43]

. Nutritional needs are similar to patients with partial-thickness burns, taking into account the extent of inflammation, the surface area affected and additional complications, such as surgery or sepsis. Early initiation of nutrition support is important to minimise weight loss and to promote wound healing[44]

.

Proposed energy requirements are 20–25kcal/kg during the early catabolic stage and 25–30kcal/kg during the anabolic recovery stage[12]

. Protein intake of at least 1.5–2g/kg/day (the same intake as patients with extensive burns) has been suggested[45]

. Micronutrient loss (especially copper and zinc) via exudate should also be considered, and supplementation (e.g. with Forceval®; Alliance Pharmaceuticals) may aid wound healing[44],[46]

. Electrolyte levels, including magnesium and phosphate, should be monitored early on in the condition and throughout admission to identify derangements owing to excessive fluid loss.

An oral diet should be initiated as soon as the patient’s condition allows it, with soft, moist and low-acidity foods, especially if oral lesions are painful[12]

. High-protein nutritional supplements may also be beneficial in meeting raised protein requirements. Nasogastric feeding should be considered if patients cannot meet nutritional requirements orally. However, in a small number of patients, nasogastric tube placement will not be possible owing to mucosal inflammation and erosion. In these patients, parenteral nutrition (known as PN) and gastrostomy feeding, such as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and radiologically inserted gastrostomy feeding (known as PEG and RIG, respectively), can be useful[12],[43]

. However, parenteral and gastrostomy feeding may not be appropriate owing to extensive epidermal detachment[46]

. In patients where enteral feeding cannot be established, there is a risk of stress-related gastric and duodenal ulceration, and so a proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed to protect against gastrointestinal bleeding[47]

.

Immunomodulation

Although the pathophysiology of SJS/TEN is driven via cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and immunocytokine pathways (see Figure 1), the role of immunomodulation remains unclear.

Ciclosporin, a calcineurin inhibitor that inhibits T-lymphocytes, given intravenously or orally, has been shown to hasten re-epithelialisation, reduce mortality and shorten length of stay as an inpatient. It is typically initiated at a dose of 3mg/kg/day in two divided doses for 7–10 days, then weaned over the course of a month (e.g. 3mg/kg/day for 10 days, 2mg/kg/day for 10 days and then 1mg/kg/day for 10 days). However, clinical studies have been small and there is no consensus on duration and place alongside other immunomodulatory agents[48],[49],[50],[51],[52]

.

Individuals taking corticosteroids appear to have a delay in the presentation of SJS/TEN[53]

and studies of high-dose corticosteroids given early to patients with SJS/TEN suggest a reduction in morbidity and mortality[12],[54]

. However, these studies were generally retrospective and do not show statistical benefit over supportive therapy alone[55]

. There is also concern that corticosteroids may increase patients’ risk of developing gastric bleeding, infections and sepsis; therefore, systemic corticosteroids are not recommended in the updated UK guidelines for the management of SJS/TEN[12]

. Although a recent meta-analysis by Zimmerman et al. suggests ciclosporin and corticosteroids show the most promise, the decision to initiate these agents should be decided under multidisciplinary review on a patient-by-patient basis[12],[51]

.

Small studies and case reports suggest tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors, such as etanercept and infliximab, may reduce mortality, but more robust research is warranted before they are used more widely[56],[57],[58],[59]

. Thalidomide, which also has TNF-α suppressive properties, should not be used because a clinical trial was stopped early owing to increased mortality[57]

. The use of cyclophosphamide in SJS/TEN has been reported so infrequently that no conclusions regarding its role can be made[51],[60],[61]

.

Human normal immunoglobulin (IVIg) has been shown to reduce keratinocyte apoptosis by inhibiting Fas–Fas ligand interactions[62]

. UK guidance identifies TEN as a high-priority indication and recommends IVIg 2g/kg as a single dose, or given over three days, when more than 10% BSA is affected and the presentation is life-threatening or other treatment is contraindicated[63]

. Although it is one of the most commonly deployed immunomodulatory agents for this condition, evidence for IVIg to reduce disease progression or mortality is contradictory and its use is generally not recommended[12],[20],[51]

.

Haematological abnormalities, such as anaemia and neutropenia, are common in SJS/TEN, with neutropenia increasing the risk of sepsis[12]

. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor can be given to manage febrile neutropenia and may have a role in halting disease progression and promoting re-epithelialisation[64]

. The Chelsea and Westminster Hospital TEN management protocol recommends subcutaneous or intravenous filgrastim in severe cases of TEN, regardless of degree of neutropenia, to promote recovery and re-epithelialisation, at a dose of around 5 micrograms/kg (0.5million units[MU]/kg) once daily, which is dose-banded in adults for ease of administration[65]

.

Other supportive management

Pain is a characteristic feature of SJS/TEN and patients should be assessed at least once per day using a patient-appropriate pain score[66]

. Patients should receive adequate background simple analgesia, such as paracetamol, and a weak opioid, such as codeine or tramadol, if required to control pain at rest (if these medicines are not suspected to be the cause of the reaction). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided owing to the potential for renal and gastric injury[12]

. Moderate-to-severe pain should be managed with strong opioids (e.g. morphine or fentanyl) delivered enterally, or by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), or infusion; although cutaneous detachment on the hands may make PCA difficult.

Additional analgesia may be required in advance of procedures such as patient handling, dressing changes and physiotherapy[66]

. Short-acting analgesia, such as morphine sulfate oral liquid (e.g. Oramorph® Boehringer Ingelheim), intranasal diamorphine, sublingual fentanyl or Entonox® (50% nitrous oxide, 50% oxygen; BOC Limited), may be useful. For patients with extensive epidermal detachment, target-controlled remifentanil infusions, bolus ketamine-based analgosedation, or even general anaesthesia may be required for wound cleansing and dressing changes[12],[67],[68]

.

All patients should receive prophylactic anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated[12]

.

Discharge and follow-up

SJS/TEN must be reported to the pharmacovigilance authorities, through the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s Yellow Card scheme in the UK[69]

.

As the patient begins to recover from SJS/TEN, consideration should be given to facilitating their discharge. The patient should be informed of the causative agent(s), once determined, and the reason why they should not be given this in the future should be discussed with them[12]

. Accurate and detailed discharge documentation is imperative to inform other healthcare professionals, especially GPs and community pharmacists, of the reaction, causative medicine, complications and follow-up plans, in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for drug allergy diagnosis and management in the UK, for example[12],[70]

. A template discharge letter can be found on the British Association of Dermatologists’ management website to support clinicians[71]

. If the causative agent cannot be identified, the patient can be referred to a local allergy service; however, the value of this is limited given the low sensitivity of allergy tests in SJS/TEN survivors[13]

. Patients should be encouraged to wear a medical alert bracelet clearly stating the name of the medicine and the reaction experienced[12]

.

Pharmacists should take time to discuss discharge medicines with patients and which medicine, or group of medicines, to avoid in future. Patients should also be advised to speak to a pharmacist before purchasing any OTC or herbal products[12]

. SJS/TEN patients will be discharged with large quantities of emollients, eye drops and dressings; therefore, it is important to notify them of this so that plans for transport can be put in place. Patients will be offered multiple follow-up outpatient appointments with the various specialities that were involved during their inpatient management — particularly dermatology and ophthalmology. Before discharge, patients should be advised on which clinics they need to attend and they should be made aware of which medicines will be resupplied from outpatient appointments, or need to be requested from their GP. The patient’s vision may continue to be impaired so pharmacists should discuss the need for compliance aids and large-print labels before making supplies for discharge. Lethargy and fatigue are common for a few weeks after discharge and suitable arrangements to attend clinics and obtain medicines should be put in place.

Finally, patients should also be counselled on support groups (such as SJS Awareness UK)[72]

, who can provide advice and empowerment for those requiring healthcare, as well as emotional and psychological support, after surviving these conditions.

- This article was amended on 3 March 2020 to correct “Moderate-to-severe pain should be managed with strong opiates (e.g. morphine or fentanyl)…” to “Moderate-to-severe pain should be managed with strong opioids (e.g. morphine or fentanyl)…

References

[1] Chave TA, Mortimer NJ, Sladden MJ & Hutchinson PE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: current evidence, practical management and future directions. Br J Dermatol 2005;153(2):241–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06721.x

[2] Frey N, Jossi J, Bodmer M et al. The epidemiology of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in the UK. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137(6):1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.01.031

[3] Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A et al. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR-Study. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128(1):35–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701033

[4] Roujeau J-C, Chosidow O, Saiag P & Guillaume J-C. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome). J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23(6):1039–1058. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70333-D

[5] Lim VM, Do A, Berger TG et al. A decade of burn unit experience with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical pathological diagnosis and risk factor awareness. Burns 2016;4(4)2:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.01.014

[6] Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M et al. ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: comparison with case-control analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;88(1):60–68. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.252

[7] Miliszewski MA, Kirchhof MG, Sikora S et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an analysis of triggers and implications for improving prevention. Am J Med 2016;129(11):1221–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.022

[8] Ferrandiz-Pulido C & Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child 2013;98(12):998–1003. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303718

[9] Frey N, Bodmer M, Bircher A et al. The risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in new users of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2017;58(12):2178–2185. doi: 10.1111/epi.13925

[10] Frey N, Bircher A, Bodmer M et al. Antibiotic drug use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: a population-based case-control study. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138(5):1207–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.12.015

[11] Sousa-Pinto B, Araújo L, Freitas A et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and erythema multiforme drug-related hospitalisations in a national administrative database. Clin Transl Allergy 2018;8(2). doi: 10.1186/s13601-017-0188-1

[12] Creamer D, Walsh SA, Dziewulski P et al. UK guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. Br J Dermatol 2016;69(6):736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.04.018

[13] Hoetzenecker W, Mehra T, Saulite I et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. F1000 Research 2016;5(951). doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7574.1

[14] Harr T & French LE. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5(39):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-39

[15] Fromowitz JS, Ramos-Caro FA & Flowers FP. Practical guidelines for the management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Int J Dermatol 2007;46(10):1092–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03277.x

[16] Roujeau JC & Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med 1994;331(19):1272–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311906

[17] Valeyrie-Allanore L & Roujeau J-C. Epidermal necrolysis (Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis). In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA & Paller A, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

[18] Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005;94(4):419–436. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61112-X

[19] Endorf FW, Cancio LC & Gibran NS. Toxic epidermal necrolysis clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res 2008;29(5):706–712. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181848bb1

[20] Schneider JA & Cohen PR. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a concise review with a comprehensive summary of therapeutic interventions emphasizing supportive measures. Adv Ther 2017;34(6):1235–1244. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0530-y

[21] Kim KJ, Lee DP, Suh HS et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: analysis of clinical course and SCORTEN-based comparison of mortality rate and treatment modalities in Korean patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2005;85(6):497–502. PMID: 16396796

[22] Dorafshar AH, Dickie SR, Cohn AB et al. Antishear therapy for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: an alternative treatment approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122(1):154–160. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181773d5d

[23] Mahar PD, Wasiak J, Hii B et al. A systematic review of the management and outcome of toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in burns centres. Burns 2014;40(7):1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.02.006

[24] Dillon CK, Lloyd MS & Dzeiwulski P. Accurate debridement of toxic epidermal necrolysis using Versajet®. Burns 2010;36(4):581–584. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.12.011

[25] Abela C, Hartmann CEA, De Leo A et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital wound management algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 2014;67(8):1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.003

[26] Dyble T & Ashton J. Case studies: emollin in practice. Br J Community Nurs 2011;16(5):222. PMID: 21650067

[27] Gueudry J, Roujeau J-C, Binaghi M et al. Risk factors for the development of ocular complications of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Arch Dermatol 2009;145(2):157–162. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.540

[28] Baudouin C, Labbé A, Liang H et al. Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly. Prog Retin Eye Res 2010;29(4):312–334. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.001

[29] Coroi MC, Bungau S & Mirela T. Preservatives from the eye drops and the ocular surface. Rom J Ophth 2015;59(1):2–5. PMID: 27373107

[30] Patel A, Cholkar K, Agrahari V & Mitra AK. Ocular drug delivery systems: an overview. World J Pharmacol 2013;2(2):47–64. doi: 10.5497/wjp.v2.i2.47

[31] Gregory DG. New grading system and treatment guidelines for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology 2016;123(8):1653–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.041

[32] Sharma N, Thenarasun SA, Kaur M et al. Adjuvant role of amniotic membrane transplantation in acute ocular Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology 2016;123(3):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.027

[33] de Prost N, Mekontso-Dessap A, Valeyrie-Allanore L et al. Acute respiratory failure in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Crit Care Med 2014;42(1):118–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829eb94f

[34] Lebargy F, Wolkenstein P, Gisselbrecht M et al. Pulmonary complications in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a prospective clinical study. Int Care Med 1997;23(12):1237. doi: 10.1007/s001340050492

[35] Koenig SM & Truwit JD. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19(4):637–657. doi: 10.1128%2FCMR.00051-05

[36] Meneux E, Paniel BJ, Pouget F et al. Vulvovaginal sequelae in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Reprod Med 1997;42:153–156. PMID: 9109082

[37] Rowan DM, Jones RW, Oakley A & de Silva H. Vaginal stenosis after toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010;14(4):390–392. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181ddf5da

[38] Meneux E, Wolkenstein P, Haddad B et al. Vulvovaginal involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective study of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:283–287. PMID: 9469290

[39] Kaser DJ, Reichman DE & Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in stevens-johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2011;4(2):81–85. PMID: 22102931

[40] Baxter CR & Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1968;150(3):874–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb14738.x

[41] Shiga S & Cartotto R. What are the fluid requirements in Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis? J Burn Care Res 2010;31(1):100–104. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181cb8cb8

[42] Kannenberg SMH, Jordaan HF, Koegelenberg CFN et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome in South Africa: a 3-year prospective study. QJM 2012;105:839–846. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs078

[43] Windle EM. Immune modulating nutrition support for a patient with severe toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Hum Nutr Diet 2005;18(4):311–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00624.x

[44] Windle M. Burn injury. In: Gandy J. Manual of Dietetic Practice. 5th edn. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014

[45] Rousseau A-F, Losser M-R, Ichai C & Berger MM. ESPEN endorsed recommendations: nutritional therapy in major burns. Clin Nutr 2013;32(4):497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.02.012

[46] Esposito G, Gravante G, Piazzolla M et al. Nutrition of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Hum Nutr Diet 2006;19(2):152–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00685.x

[47] Yang YX & Lewis JD. Prevention and treatment of stress ulcers in critically ill patients. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2003;14(1):11–19. PMID: 12610850

[48] Kirchhof MG, Miliszewski MA, Sikora S et al. Retrospective review of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treatment comparing intravenous immunoglobulin with cyclosporine. J Am Dermatology 2014;71(5):941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.016

[49] Singh GK, Chatterjee M & Verma R. Cyclosporine in Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and retrospective comparison with systemic corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79(5):686–692. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.116738

[50] Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Brochard L et al. Open trial of ciclosporin treatment for Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol 2010;163(4):847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09863.x

[51] Zimmermann S, Sekula P, Venhoff M et al. Systemic immunomodulating therapies for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. JAMA Dermatology 2017;153(6):514. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5668

[52] Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69(2):187e1–187e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002

[53] Lee HY, Dunant A, Sekula P et al. The role of prior corticosteroid use on the clinical course of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case–control analysis of patients selected from the multinational EuroSCAR and RegiSCAR studies. Br J Dermatol 2012;167(3):555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11074.x

[54] Tripathi A, Ditto AM, Grammer LC et al. Corticosteroid therapy in an additional 13 cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: a total series of 67 cases. Allergy Asthma Proc 2000;21(2):101–105. PMID: 10791111

[55] Schneck J1, Fagot JP, Sekula P et al. Effects of treatments on the mortality of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: a retrospective study on patients included in the prospective EuroSCAR Study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.039

[56] Paradisi A, Abeni D, Bergamo F et al. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71(2):278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.044

[57] Kreft B, Wohlrab J, Bramsiepe I et al. Etoricoxibâ€induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol 2010;37(10):904–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00893.x

[58] Wojtkiewicz A, Wysocki M, Fortuna J et al. Beneficial and rapid effect of infliximab on the course of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol 2008;88:420–421. PMID: 18709327

[59] Wang CW, Yang LY, Chen CB et al. Randomized, controlled trial of TNF-α antagonist in CTL-mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions: supplemental data. J Clin Invest 2018;128(3):985–996. doi: 10.1172/JCI93349DS1

[60] Heng MCY & Allen SG. Efficacy of cyclophosphamide in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25(5):778–786. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(08)80969-3

[61] Frangogiannis NG, Boridy I, Mazhar M et al. Cyclophosphamide in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis. South Med J 1996;89(10):1001–1003. PMID: 8865797

[62] Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science 1998;282(5388):490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.490

[63] Department of Health. Clinical guidelines for immunoglobulin use (second edition update). 2011. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clinical-guidelines-for-immunoglobulin-use-second-edition-update (accessed May 2019)

[64] Ang C-C & Tay Y-K. Hematological abnormalities and the use of granulocyteâ€colonyâ€stimulating factor in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Int J Dermatol 2011;50(12):1570–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05007.x

[65] De Sica-Chapman A, Williams G, Soni N & Bunker CB. Granulocyte colonyâ€stimulating factor in toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Chelsea & Westminster TEN protocol. Br J Dermatol 2010;162(4):860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09585.x

[66] Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Colin A et al. Prise en charge de la douleur dans le Syndrome de Stevens-Johnson/Lyell et les autres dermatoses bulleuses étendues [Pain management in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and other blistering diseases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2011;138(10):694–697. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2011.05.029

[67] Struys MMRF, De Smet T, Glen JIB et al. The history of target-controlled infusion. Anesth Analg 2016;122(1):56–69. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001008

[68] Erstad BL & Patanwala AE. Ketamine for analgosedation in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2016;35:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.05.016

[69] MHRA. Yellow Card scheme. 2014. Available at: https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/ (accessed May 2019)

[70] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Drug allergy: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG183]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg183 (accessed May 2019)

[71] British Association of Dermatologists. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. 2016. Available at: http://www.bad.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/clinical-standards/clinical-guidelines/sjs-ten (accessed May 2019)

[72] SJS Awareness UK. 2018. Available at: https://www.sjsawareness.org.uk (accessed May 2019)

[73] Frey N, Bodmer M, Bircher A et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in association with commonly prescribed drugs in outpatient care other than anti-epileptic drugs and antibiotics: a population-based case–control study. Drug Saf 2018;42(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0711-x

[74] Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115(2):149–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x