DermNet

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the complexities of diagnosing dermatological conditions in skin of colour;

- Identify common dermatological conditions in skin of colour;

- Understand the presentation of common dermatological conditions in skin of colour.

Identifying common skin conditions in skin of colour (SOC) is inherently difficult for healthcare professionals owing to the lack of inclusivity and representation in medical textbooks and practical training, which have historically focused on Caucasian/light skin tones[1]. These biases in teaching and training have led to delays in diagnosis and appropriate treatment in people of colour, leading to greater morbidity and mortality in this patient group[2,3]. In the UK, 54% of the population is affected by skin disease annually, with 23–33% of the UK population having skin conditions that would benefit from medical care. In children, 34% of diseases are skin-related, with atopic eczema affecting 20% of infants[4].

Delayed diagnosis may result in increased severity of a skin condition, leading to increased itching, dryness, skin thickening and hyperpigmentation owing to the prolonged inflammation[5]. This can result in a need for more aggressive and prolonged treatments once a diagnosis is made[2]. A UK study involving 287 GPs showed that, in primary care, malignant melanomas were significantly underdiagnosed in darker skin compared with lighter skin types[6]. The ability to diagnose and understand the main differences in the presentation of redness, inflammation and scaling present in common skin conditions between different skin tones is imperative for pharmacists to properly serve diverse populations[1].

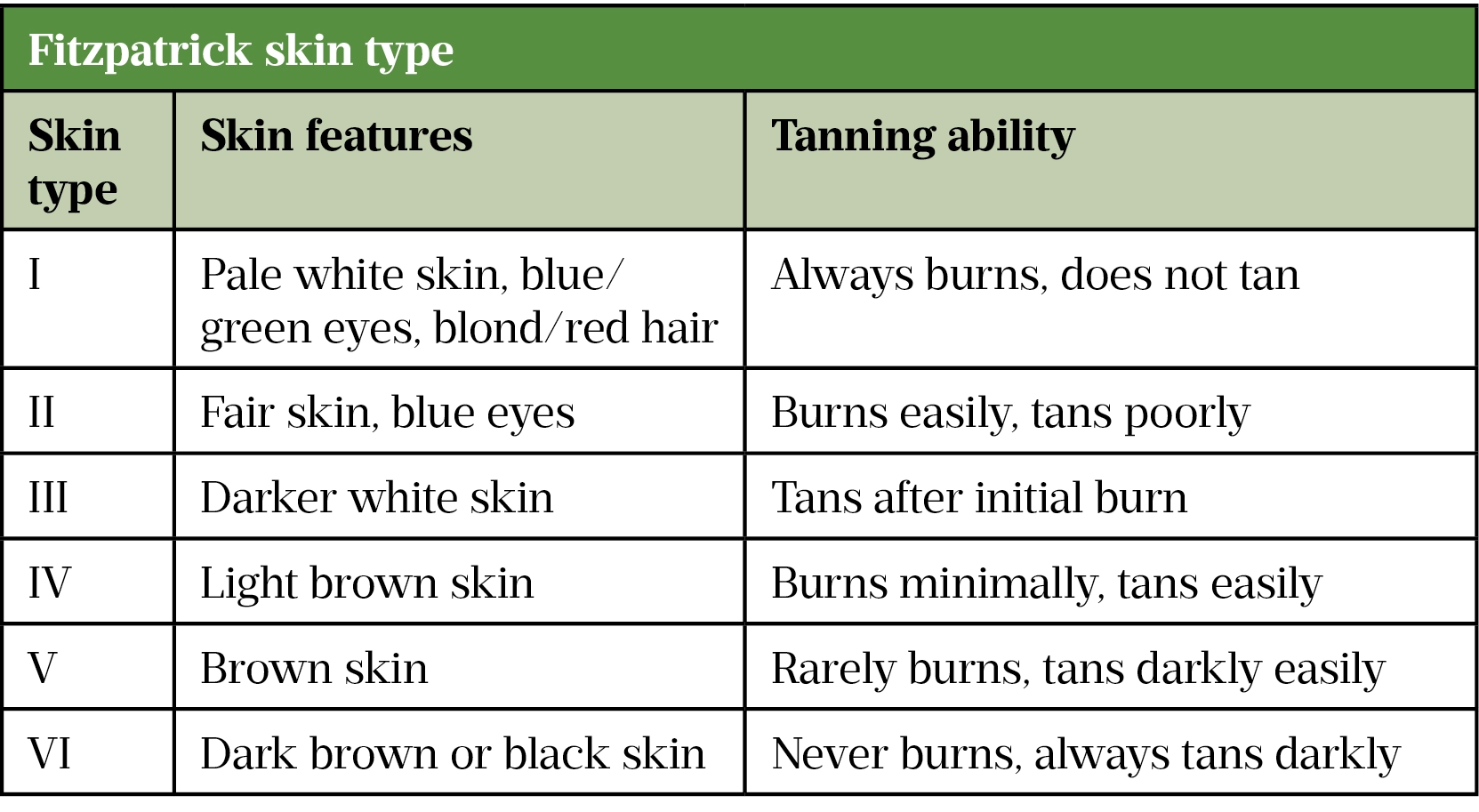

The Fitzpatrick scale (see table) describes skin according to its reaction to sun exposure, which is dependent on the amount of melanin in the skin, and will be used when discussing skin types throughout this article[7].

Darker skin types are more prone to post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), as described in an earlier PJ article ‘Common dermatological conditions in skin of colour‘[1]. The common presentation of redness, scaling and inflammation that is easily visible on fair skin is less likely to present in the same manner in darker skin tones, making diagnosis difficult[8].

Once the correct diagnosis has been made — accounting for the potential for variation in presentation — in most cases, the management of dermatological conditions is the same regardless of skin type. For this reason, the management of these conditions will not be discussed in detail, but a summary of best practice is included later in the article[2]. This article aims to aid pharmacists in the identification of several common dermatological conditions that pharmacists may encounter in SOC by outlining their characteristic features and any relevant diagnostic questions.

Community pharmacists play a pivotal role in supporting patients of colour who present with inflammatory skin conditions. Patients should be supported and advised on how to manage their symptoms through best use of emollients, lifestyle changes, managing triggers, proper use of prescribed topical treatments, and recognising signs of infection as this would require referral to their GP or dermatologist.

Eczema

Atopic dermatitis (i.e. eczema) is a commonly occurring chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically presents in the first year of life[9]. Pruritic (i.e. itching), erythematous (i.e. inflamed and red) plaques with fine overlying scale typically develop on the flexor surfaces, such as the skin on the side of a joint that folds; for example, the crooks of elbows, back of the knees and posterior neck[9]. Establishing the length of time the condition has been present is essential, as well as the frequency of flare ups and triggers. Eczema affects 1 in 5 children and 1 in 12 adults in the UK[10]. Differences between incidence in lighter and darker skin tones is not known in the UK; however, a US study has suggested that eczema is more common in black children[11].

Although the general presentation of eczema is considered similar among different skin tones, the appearance may be difficult to recognise in SOC. Presentations such as erythema, which is easily visible in lighter skin tones, is masked in SOC owing to skin being naturally darker. This can lead to late diagnosis, treatment delays and more advanced disease at the point of diagnosis, with hospital admissions shown to be up to six times higher in patients of colour[9,12,13].

There is increased scaling and lichenification (i.e. thickening) in eczema in SOC, compared with fairer skin, which has been linked to genetic mutations, such as the filaggrin or interleukin mutations, and immune pathway differences, such as differences in thymic stromal lymphopoietin, interferon regulatory factor 2 and Toll-like receptor 2 in Asian and black skin, compared with Caucasian skin[9,14].

Signs and symptoms of eczema in SOC include:

- Pruritus — intense itching is extremely common in all skin types;

- Erythema — may appear more purple in SOC, whereas it is red in lighter skin;

- Dryness of the skin — presents as white, fine flaking in darker skin;

- Scaly plaque in the flexure surfaces in all skin tones. The neck is a commonly affected area in Asian and black skin;

- Lichenification that feels thick/rough to the touch and is often hyperpigmented in SOC;

- Hyper- and hypopigmentation is common and presents with greater severity in darker skin tones, compared with lighter skin[15–17].

The treatment of eczema is not affected by ethnicity or Fitzpatrick skin type[9,14]. However, as PIH is of greater concern than the skin condition itself in SOC, it is important to minimise this risk by managing inflammation with appropriate steroid use and skin hydration with the appropriate emollient application.

A simple skincare routine with a gentle cleanser that does not leave the skin feeling dry after use should be advised. This keeps the skin well hydrated and prevents further dryness and irritation, as this can lead to increased stretching, eczema flares and worsening PIH[18]. Patients with moderate-to-severe dermatitis that are not responding to topical treatments should be referred to their GP for a secondary care referral, as they may benefit from oral treatments such as oral steroids and systemic immunosuppressants. Signs of infection should also be referred for appropriate antibiotic treatment[10].

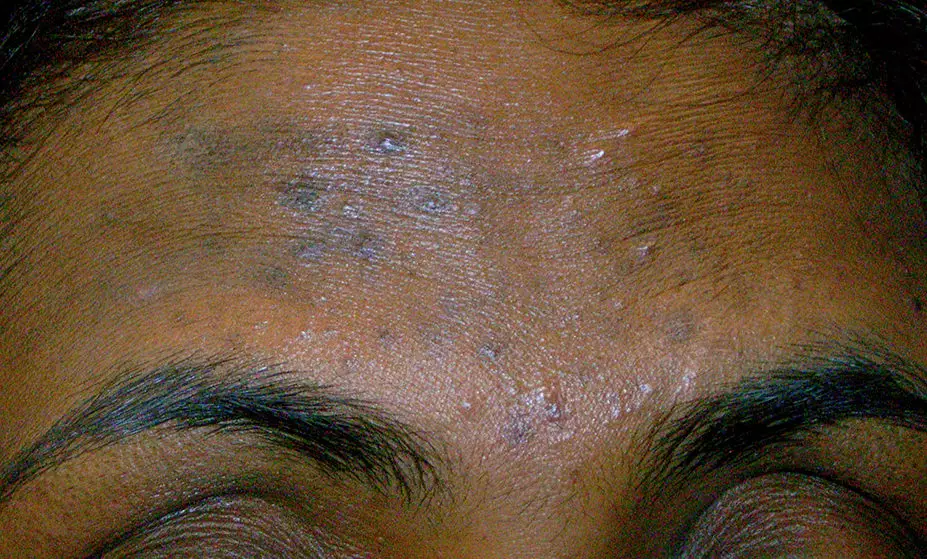

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition defined by sharply demarcated erythematous (a clear definition and border between inflamed and normal skin), silvery, scaly plaques that are most often seen on the scalp and external flexures; the nails, hands and trunk can also be affected[19].

Inflammatory plaques are typically pruritic and will often result in either post-inflammatory hyper- or hypo-pigmentation in SOC[8]. There is often a ring of intense erythema surrounding the scaly plaques, as well as erythematous papules surrounding existing plaques — this is uniform across skin types. Once plaques have resolved, there is decreased scale and central clearing. If nails are involved, look for pitting[20].

When diagnosing psoriasis in SOC, look for sharply demarcated erythematous, silver-scaled plaques. Erythema is more subtle in darker skin tones and papules can appear more pink, violaceous, grey or even dark brown in colour. PIH is common after erythema has resolved in SOC[21]. A patient history should be taken to understand when symptoms first started; if there is a family history; and where on the body plaques often appear, the nature of their appearance and if they are pruritic[22].

For psoriasis that is not responding to treatment, interferes with daily life (prevents the patient from social or physical activities, employment or education) or is causing distress, such as a negative impact on mental health, the patient should be referred to dermatologists in secondary care via a GP[23].

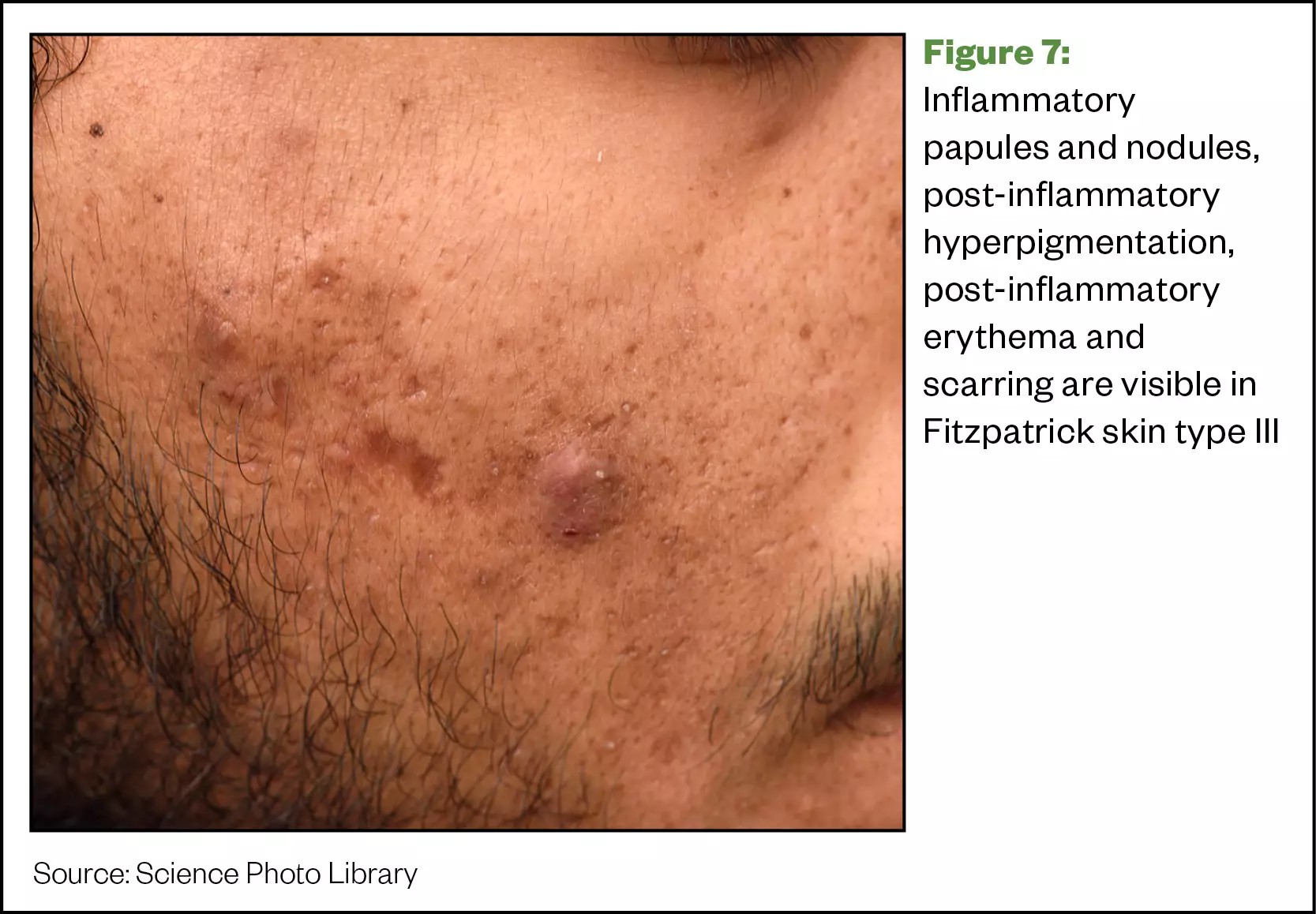

Acne vulgaris

Acne is an inflammatory skin condition of the pilosebaceous units in the skin. Acne lesions are typically classified as inflammatory and consist of papules and pustules, or non-inflammatory lesions, most often referred to as open and closed comedones[24].

Papules are solid, raised palpable lesions that are less than 1cm in diameter. Pustules are of a similar size but are filled with pus[25].

Comedones are defined as pores that are filled with dead skin debris and sebum[25]. Even though the contents of these pores are the same, closed comedones are often referred to as whiteheads because they are under the skin, while open comedones are often called blackheads because of the oxidation of the debris resulting in a black colour.

Post-inflammatory erythema (PIE) is where small, red and flat spots are left behind after the acne lesion heals[25]. PIE, scarring and PIH are possible symptoms of acne, as well as excess oil production[24,26].

Clinically, there is no difference in the appearance of acne lesions in Caucasian skin compared with SOC; however, histologically, there is more inflammation associated with SOC, even with smaller lesions such as comedones. This results in PIH and scarring more commonly occurring in SOC than in Caucasian skin[27].

Acne is the most commonly diagnosed skin condition in SOC[28]. Common differential diagnoses include perioral dermatitis (POD), folliculitis, rosacea and milia.

The following questions can be considered to aid diagnosis, especially in patients with SOC, as sometimes the redness is not fully visible:

- How quickly did these lesions appear on the face?

- Folliculitis lesions appear quicker and are more uniform, whereas acne lesions will be more irregular.

- Where are the majority of the lesions located on the face?

- POD affects the area around the mouth and nose and sometimes the corners of the eyes;

- Rosacea presents on the central parts of the face, such as on the nose and the nose itself, as well as the chin and space between the eyebrows. There is also redness associated with the papules.

- Milia look like small, skin-coloured bumps and mainly occur around the eye area and at the top of the cheeks.

- Are any treatments currently being used? If so, is there any soreness or itchiness?

- POD is often triggered by topical steroid use, certain cosmetics or SPF products.

Acne treatment can take around six weeks to begin taking effect[29]. However, once acne has healed, PIH can occur, causing skin to appear darker owing to an abnormal release or overproduction of melanin during the healing process[26]. Keloidal scars are firm, smooth and hard growth resulting from scar formation[25]. These types of scars are more commonly seen in SOC in comparison with Caucasian skin as there is more inflammation present, increasing the likelihood of their development[28].

In patients with SOC, the resulting PIH can be more distressing than the acne itself[26]. The duration of PIH can last much longer than the total duration of acne, with epidermal PIH (occurring on the top layer of the skin) taking around 6–12 months to heal, and dermal PIH (occurring below the epidermis) potentially lasting for years afterwards[26].

There are considerations required for management of acne in SOC. Treatment must be aggressive enough to minimise the risk of recurrence, without causing irritation that leads to PIH; therefore a good balance is needed[26]. This can be achieved by using strengths of treatment that the patient can tolerate without any side effects.

Effective skincare recommendations alongside the treatment should also be considered, as a simple cleanser, moisturiser and sunscreen without any other active ingredients will help reduce the likelihood of irritation and other side effects. This is true for all skin types but will be especially beneficial to patients with SOC to prevent further PIH.

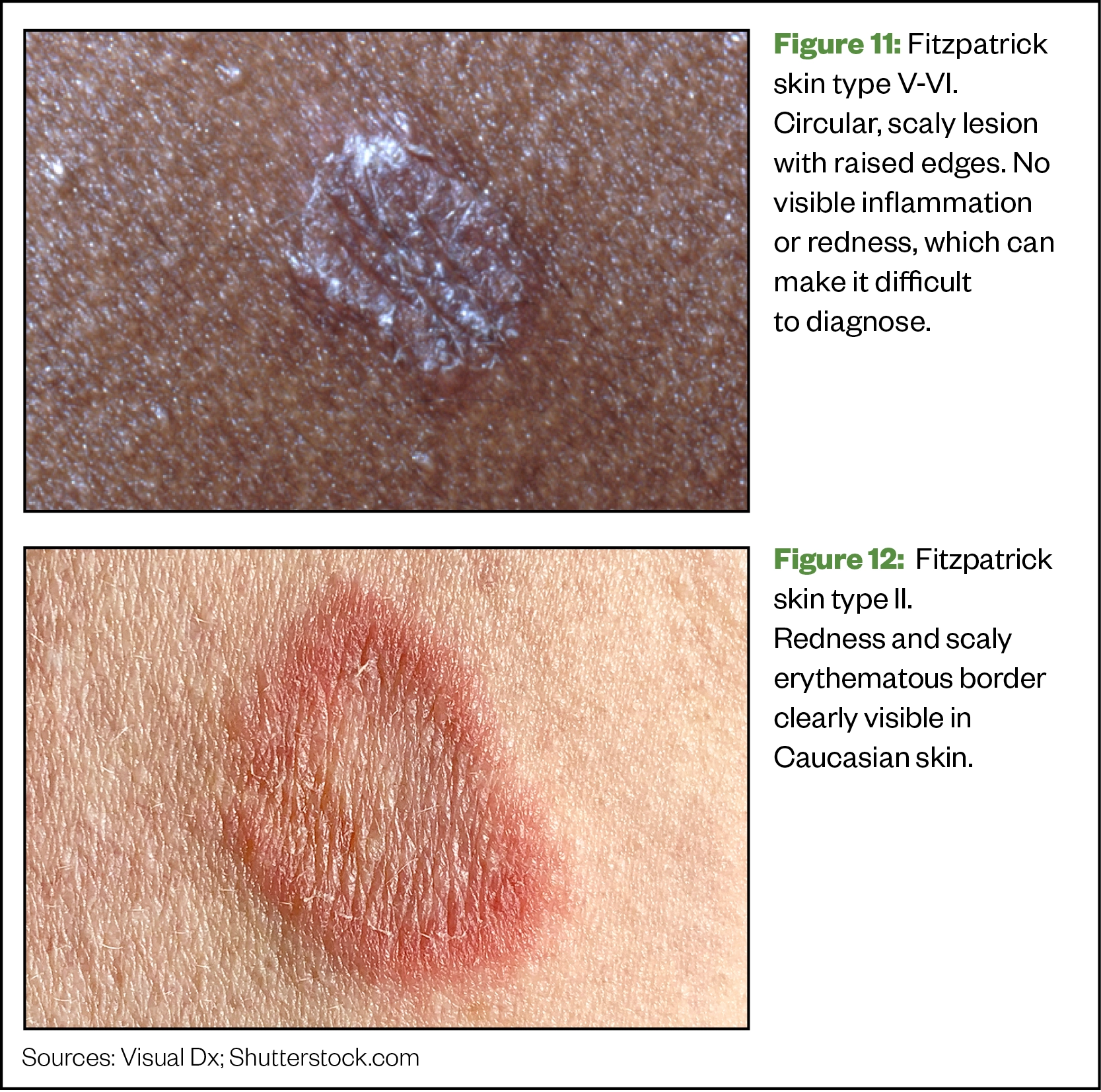

Fungal skin infection — ringworm

Ringworm (Tinea corporis) is a fungal infection of the skin that presents with a ring-shaped lesion[30]. It can be passed on after contact with infected people and animals, as well as infected items, such as bedsheets, towels and combs[30]. This lesion may be scaly, dry, inflamed and itchy and can appear anywhere on the body, including the scalp (Tinea capitis) and groin (jock itch)[30].

Differential diagnoses include psoriasis, scabies, seborrheic dermatitis and contact dermatitis. The circular lesion is the most common way to identify ringworm and rule out alternatives; however, there are some questions that can be used to rule out differential diagnoses:

- Where is the lesion located primarily?

- Seborrheic dermatitis and contact dermatitis are more likely to present as larger lesions that may be symmetrical, even though there may be similar symptoms;

- Scabies presents most commonly between the fingers or genital areas and can spread quickly over the whole body.

- Have you been in contact with anyone/any animal that may have been infected with ringworm?

- How does the lesion feel? Scaly, itchy or dry?

- Psoriasis lesions are more plaque-like, where there is a raised patch of skin with a silvery scale.

Ringworm can sometimes be hard to distinguish when diagnosing patients with SOC because the characteristic redness may be difficult to observe; however, the location of the lesion on the body and the circular rash with scale are the main diagnosing factors.

Management

PIH resulting from inflammatory skin conditions can have a large disease burden in patients with SOC and can be as concerning as the skin condition itself[8]. For this reason, reducing inflammation should be the focus of treatment, while ensuring the risk of side effects from topical treatment is minimised, as skin peeling and irritation can result in PIH[31].

Chronic inflammatory skin conditions can also cause vast psychological distress, owing to the impact of skin disease and the resulting pigmentation — which can be severe and for a prolonged period in SOC — on self-esteem and self-image, leading to depression and anxiety. It is important to manage the symptoms of the skin condition and monitor the mental health of the patient[32].

Best practice

Things to consider when diagnosing dermatological conditions in SOC:

- In SOC, there may not be classic signs of redness or inflammation and it is important to be aware of this difference compared with Caucasian skin. Observe where the skin condition is presenting and take an in-depth history, including family history;

- PIH is a major concern in patients with SOC. It is important that this is addressed and that patients are reassured that, with the right treatment, the condition will improve over time;

- Ensure that your patient has a gentle skincare routine that does not result in skin dryness, as this can cause worsening of some inflammatory conditions and promote PIH;

- Skin hydration is essential to managing symptoms and PIH, ensure the patient knows how and when to use their emollients.

- Patients with severe symptoms that are not controlled with over-the-counter or currently prescribed treatment should be referred to their GP/dermatologist.

Available resources to help with identifying common skin conditions in skin of colour

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

This article has been reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in November 2021.

- 1Perlman KL, Williams NM, Egbeto IA, et al. Skin of color lacks representation in medical student resources: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 2021;7:195–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.12.018

- 2Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020;83:957–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- 3Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren M ‐M. Under‐representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1521–2. doi:10.1111/bjd.17608

- 4Levell N, Jones S, Bunker C. Dermatology. British Association of Dermatologists. 2013.https://www.bad.org.uk/library-media/documents/consultant%20physicians%20working%20with%20patients%202013.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 5Siegfried E, Hebert A. Diagnosis of Atopic Dermatitis: Mimics, Overlaps, and Complications. JCM. 2015;4:884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- 6Lyman M, Mills JO, Shipman AR. A dermatological questionnaire for general practitioners in England with a focus on melanoma; misdiagnosis in black patients compared to white patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;31:625–8. doi:10.1111/jdv.13949

- 7Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Archives of Dermatology. 1988;124:869–71. doi:10.1001/archderm.124.6.869

- 8Davis E, Callender V. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3:20–31.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20725554

- 9Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-Variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340–57. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- 10Single Technology Appraisal Dupilumab for treating adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis [ID1048] final scope. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta534/documents/final-scope (accessed Nov 2021).

- 11Fischer AH, Shin DB, Margolis DJ, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization for childhood eczema: An analysis of the 2001-2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017;77:1060–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.035

- 12Torrelo A. Atopic dermatitis in different skin types. What is to know? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:2–4. doi:10.1111/jdv.12480

- 13Janumpally SR, Feldman SR, Gupta AK, et al. In the United States, Blacks and Asian/Pacific Islanders Are More Likely Than Whites to Seek Medical Care for Atopic Dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.5.634

- 14Leung DYM. Atopic dermatitis: Age and race do matter! Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015;136:1265–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.011

- 15Murota H, Katayama I. Exacerbating factors of itch in atopic dermatitis. Allergology International. 2017;66:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2016.10.005

- 16Pakran J. Sparing phenomena in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:545. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.113104

- 17How should I diagnose atopic eczema? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/diagnosis/diagnosis/ (accessed Nov 2021).

- 18Heath C. Managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis 2019;103:71–3.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30893390

- 19Ayala F. Clinical presentation of psoriasis. Reumatismo 2007;59 Suppl 1:40–5.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17828342

- 20Jiaravuthisan MM, Sasseville D, Vender RB, et al. Psoriasis of the nail: Anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature on therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;57:1–27. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.073

- 21Alexis A, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2014;7:16–24.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25489378

- 22Psoriasis: diagnosis and treatment. American Academy of Dermatology Association. 2021.https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/psoriasis/treatment/treatment (accessed Nov 2021).

- 23Assessment of psoriasis and referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/ifp/chapter/assessment-and-referral#assessment-of-psoriasis-and-referral (accessed Nov 2021).

- 24Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology. 2013;168:474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149

- 25Oakley A, Ngan V, Morrison C. Acne vulgaris. DermNet NZ. 2014.https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acne-vulgaris (accessed Nov 2021).

- 26Alexis AF, Harper JC, et al. Treating Acne in Patients With Skin of Color. Sem Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:S71–3. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.027

- 27Davis E, Callender V. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3:24–38.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20725545

- 28Callender V, Alexis A, Daniels S, et al. Racial differences in clinical characteristics, perceptions and behaviors, and psychosocial impact of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2014;7:19–31.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25053980

- 29Acne — treatment. NHS. 2019.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/acne/treatment/ (accessed Nov 2021).

- 30Bell H, Mitchell G. Tinea corporis. DermNet NZ. 2020.https://dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-corporis (accessed Nov 2021).

- 31Shah S, Arthur A, Yang Y, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol 2011;10:866–72.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21818507

- 32Jafferany M. Psychodermatology. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;09:203–13. doi:10.4088/pcc.v09n0306