Andrea De Martin / Alamy Stock Photo

After reading this article individuals should be able to:

- Understand the transition process and what is involved;

- Understand the impact transition can have on young people and their families;

- Understand how pharmacists can contribute to the transition process;

- Identify areas of opportunity to contribute to transition within own practice.

The transition from childhood to adulthood is a time of great change, both emotionally and physically, for any young person, but particularly for those living with a long-term condition. Young people aged 10–19 years represent 11% of the total population of the UK and those aged 10–24 account for 18% of the population[1]. In England, more than 80,000 young people aged under 18 years are living with a life-threatening or life-limiting condition[2]. In addition, 23% of those aged 11–15 years report having a long-term illness or disability[3].

The need to transition from paediatric to adult healthcare services is a unique challenge to young people. This transition, without the appropriate planning and communication between healthcare providers, is associated with increased morbidity and mortality[4–7].

Transition is defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as “a purposeful, planned process that addresses the medical, psychosocial and educational/vocational needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions as they move from child-centred to adult-oriented healthcare systems”[8]. Studies show that the transition process should begin at around 11–12 years of age as this leads to improved knowledge, skills and the confidence required to move to adult services[4,9]. A successful transition between paediatric and adult care improves long-term outcomes for patients and their families[5,10]. However, the quality of transition services within the UK vary, with only 50% of young people and their carers stating that they have received support from a healthcare professional overseeing the transition process prior to, during and immediately after transition to adult care[11].

This article aims to improve understanding of the issues young people face when transitioning to adult services and provides practical advice for pharmacy teams to help manage this process.

Guideline-based best practice

Good transition is crucial to ensure young people and their carers feel supported and empowered during a potentially unsettling time[10,12,13]. A period of overlap with paediatric and adult care services allows good collaboration and effective communication between care providers, the young person and their family. It also ensures the young person feels a part of the decision-making process, and allows time for any issues or concerns to be highlighted[10,12].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence quality statements

In 2016, NICE published five quality statements to help improve care for young people transitioning to adult services[8]. The quality statements cover the period before, during and after transfer of care for patients aged up to 25 years and include all health and social care settings. In summary:

- For young people with long-term conditions, transition planning should start by school year 9 (aged 13–14 years), or immediately if the young person enters paediatric services after school year 9;

- There should be an annual meeting to review transition planning;

- Each young person should have a named worker to coordinate care and support before, during and after transition;

- Young people should meet a practitioner from each of the adult services they will move to prior to transition;

- Young people who do not attend their first meeting or appointment should be contacted by adult services and given further opportunities to engage[8].

The transition team

Good transition to adult services requires a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to ensure holistic, well-rounded care by considering the medical, psychosocial and vocational needs of the young person[12,14–16]. The young person’s GP should be involved throughout the entire process, especially in situations where there is no equivalent adult service for patients who may be under more than one paediatric specialist team (e.g. a child with complex medical needs)[8]. There should also be a named worker from both paediatric and adult services to coordinate the development and implementation of the transition care plan as described below[8,11].

Paediatric nurse specialists (e.g. diabetes or epilepsy) should be part of the transition process as they are able to highlight key issues to the adult team. Many hospitals now employ transition nurses, whose role it is to act as the named worker for the young person and to support the patient to take responsibility for their health needs in preparation for adult services.

Commissioner and/or service planner involvement is necessary to provide resource support for transition planning and to monitor the effectiveness of transition services to drive improvements, such as readmission rates or patient experience[8].

At the core of the MDT should be the young person, their family and/or carers, who should be consulted and kept informed throughout the process[3,8].

The pharmacist’s role

The role of the pharmacist in transition is not well understood and needs development within the UK. Currently, there is no standardised guidance outlining pharmacist involvement in the transition process. Poor transition can result in problems with medication adherence and self-management — issues where pharmacists should be involved, regardless of sector or specialty[3].

A recent study of UK hospital pharmacists supports the role of pharmacists as crucial members of the multidisciplinary team required for transition. Respondents to a questionnaire identified unique skills that pharmacists could contribute to the transition service, including knowledge of medications (including formulations and unlicensed medications), awareness of medication services beyond paediatrics, commissioning of medications and familiarity with adult services[17].

Pharmacists should aim to inform and empower young people to take ownership of their treatment by addressing questions directly to the young person, where possible, and including them in decisions about their health and medications[8]. Information and advice on medicine adherence, side effects, interactions and supply should also be provided. Pharmacists should allow young people and their families the opportunity to express any concerns and, if necessary, be willing to liaise with other healthcare providers on behalf of the patient[8]. Pharmacists should also encourage patients to ask questions and to seek pharmacist advice whenever needed.

Along with the usual patient consultation questions, pharmacists can ask the following to determine a young person’s understanding of their condition and medication therapy:

- Has someone explained to you what this medication is for and how to take it?

- What information have you been provided?

- How do you usually take your medicine?

- Do you know what to do if you miss a dose?

- How do you find taking your medication?

- What concerns you most about your condition and taking your medication?

These questions allow pharmacists to address knowledge gaps and tailor advice to the individual patient and their family.

Community pharmacists can actively engage in conversation with young people, particularly around knowledge and perception of their condition and medications, as well as adherence and supply issues[18]. Young people should be encouraged to be present in the pharmacy when their medicines are being supplied to create opportunities for conversation and to enable medicines optimisation.

Within a hospital setting, pharmacists working in specialist centres may already be involved in transition (e.g. cystic fibrosis, diabetes and transplant) and actively contribute to meetings with the young person, their family and members of the paediatric and adult care MDTs. This provides the opportunity for paediatric pharmacists to communicate the type of support patients and their families need to the pharmacy team within the adult service[18]. In most instances, paediatric pharmacists can liaise with GPs or practice pharmacists to organise repeat prescriptions for patients and communicate any concerns. This ensures medicines supply is not interrupted and creates a dialogue between specialist and primary care[18]. However, patients on high-cost (e.g. those commissioned by NHS England) or difficult to source medications may still be linked to their paediatric centres after transition because of medicine supply issues. Prescribing responsibility for such medications (e.g. tacrolimus) is usually transferred from specialist to adult or local services when it is deemed possible or appropriate. Paediatric pharmacists can ensure any changes to medications are communicated to relevant services to minimise the risk of medication-related harm[18]. For example, a paediatric pharmacist is able to ensure the local adult service will provide ongoing supply of as many medications as possible for a particular patient. This is important because it can be difficult for families to obtain medications from multiple pharmacies.

Paediatric pharmacists can also coordinate temporary supply of certain drugs for a patient from their paediatric centre after their transition. This is to allow time for an adult service to apply for funding to supply those medications. It is crucial that pharmacists highlight this change to young people and their families to avoid confusion and minimise any disturbance to medication supply[18].

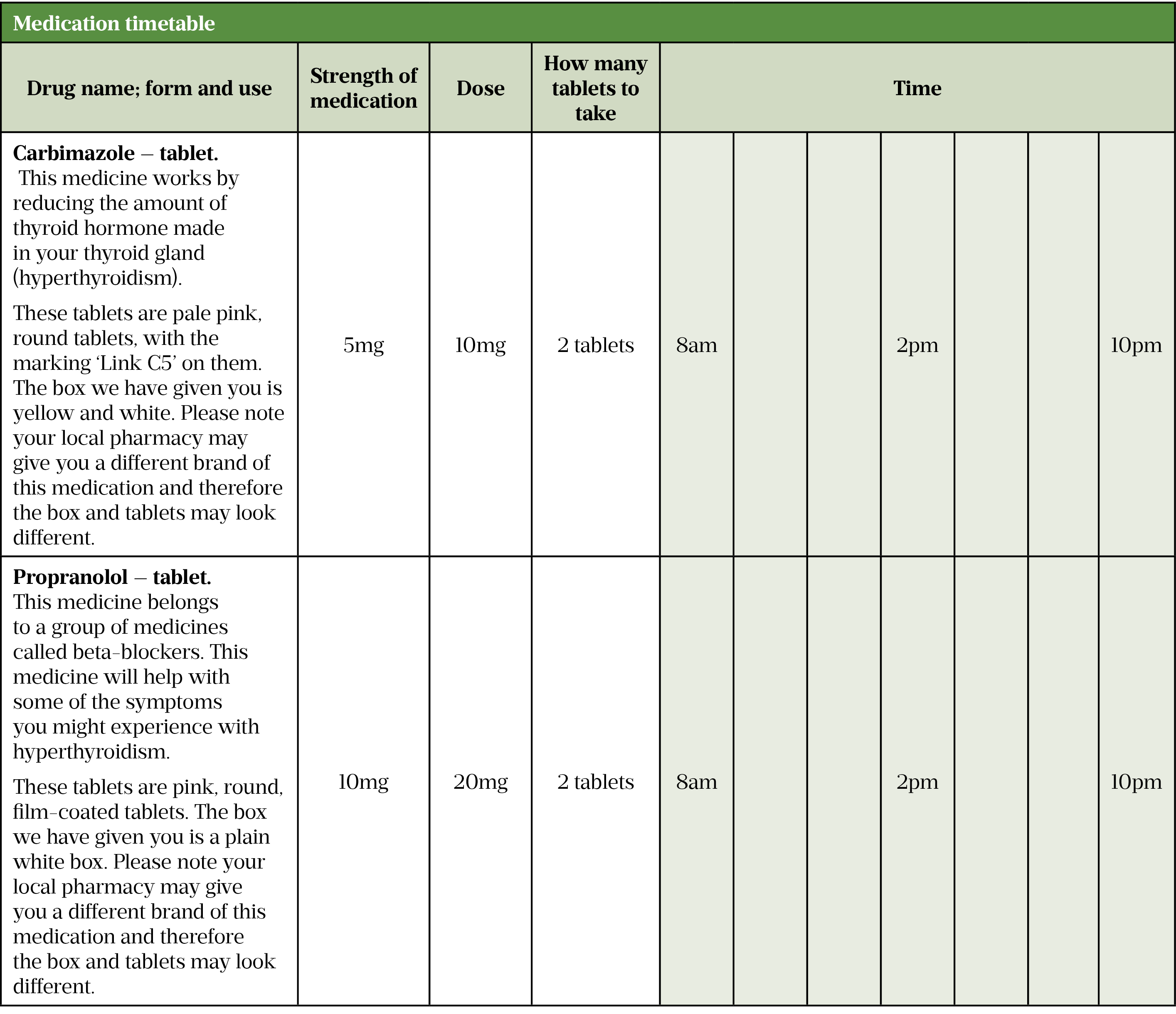

Unfortunately, established transition programmes are not guaranteed in district general hospitals where a gap in service provision may exist[11]. Regardless, pharmacists within paediatric and adult care services can still contribute at an individual patient level by providing medicines education to young people and their families to promote independent therapy management while in hospital and at home. For example, preparing a take-home medication card (see Table 2) for a young patient newly diagnosed with a long-term condition (e.g. hyperthyroidism), which sets out their new and existing prescribed medications, indication, dose, administration times and any other relevant information, such as how to differentiate between tablets and what side effects to look out for. Young patients may find their new diagnosis overwhelming and pharmacists are able to allay some of the patient’s concerns by using the card to facilitate discussion.

Transition planning

An effective, well-planned transition is essential for a smooth transfer into adult care. An ideal transition plan meets the needs of all involved, considers the thoughts and opinions of the young person and their family and allows the young person to manage their healthcare successfully.

Below is a suggested plan based on the work of Nagra et al. and current NICE guidance.

Sources: Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed[4], NICE[8], Child Care Health Dev[9], Care Quality Commission[11]

- Timing and review

Around the age of 12 or 13 years, the paediatric team should begin planning for transition[4,8,9,11]. The exact time for when this should happen differs for each child and should occur during a period of relative stability as opposed to depending on age.

Classically, it is thought that transition planning should start when a young person is aged 13–14 years, but other evidence suggests that it should start sooner and be a more gradual process[4,8,9,19]. Studies show that starting transition planning at around 11–12 years of age leads to better patient knowledge and skills[4,9]. It also means the young person and their family have time to gain the confidence needed to move to adult services.

Meetings should be held at least annually with parents/caregivers to review transition planning, with the outcome of each meeting shared with all those involved[8,11]. These meetings aim to:

- Facilitate communication between care providers;

- Involve the young person and their family in planning and decision making;

- Inform all parties of updates to care or the transition plan[8].

2. Named worker

A named worker should be appointed to coordinate and oversee transition[8,11]. They are the point of contact for the young person and their parents, and the link between healthcare providers.

It is the responsibility of the named worker to liaise with the MDT, and ensure details and information regarding care are up to date[8]. This is in addition to ensuring the young person remains engaged with the process by providing support and advice relating to education, employment, independent living, health and wellbeing[8].

Named workers should be chosen based on the needs of the patient and can be from any health or social care background (e.g. a doctor, nurse or social worker)[8]. Therefore, a pharmacy professional actively involved in helping a young person struggling to independently manage their own therapy could be a named worker.

3. Building independence

A good transition includes encouraging young people to build social and recreational networks to aid transition and provide opportunities to gain independence[8,11]. The young person’s ability to manage their long-term condition should be assessed and support offered where appropriate (e.g. peer support groups, coaching and education, advocacy or mobile technology/digital health passports). See below for additional resources[8].

4. Before transition

At least three months prior to transfer of care, young people and their families should have the opportunity to meet with relevant health and social care workers from adult services[8,11]. This can be done via joint clinics with paediatric healthcare providers. If possible, the young person should be encouraged to share information about themselves in a manner of their choosing (e.g. written document)[8]. The information will be used to create a personal folder for the patient, which will facilitate development of the patient-clinician relationship prior to transfer of care and inform adult services of the health and social care needs of the young person, including emergency/contingency plans, history of unplanned admissions, the individual’s strengths and future goals, as well as the young person’s preferences for parent and/or carer involvement[8]. It is important to respect these preferences while considering their ability to make such decisions as per the Mental Capacity Act[8,20].

5. After transition

The named worker should continue to play an active role in the young person’s care for up to six months post transition or for as long as the young person requires support[8]. For consistency, it is also important that the young person sees the same adult services practitioner for the first two appointments[8]. Should there be any issues with engagement, care or attendance at appointments, a discussion between the young person, their family and relevant members of the transition team should occur (e.g. GP and social care services)[8].

A case of poor transition

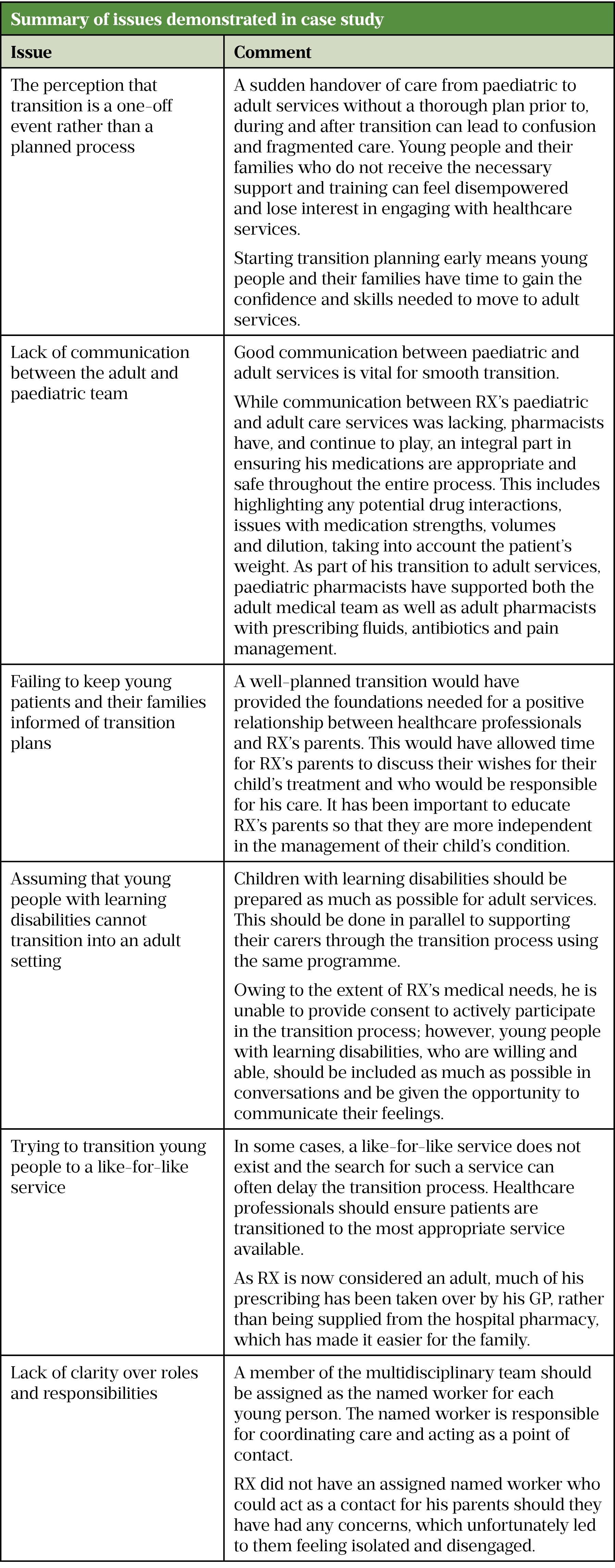

The following anonymised case study is an example of poor transition. It highlights many of the issues young people face when moving to adult care services. These issues are explored further in Table 1. Consent for this case to be used was obtained from the patient’s parents.

Case study: RX is a male patient, aged 19 years, with a very rare genetic degenerative brain condition. He is registered blind, and has partial hearing, a gastrostomy, a suprapubic catheter, lung disease and is oxygen dependent. He is cared for full time by his parents and siblings. Owing to his medical conditions, RX is on several complex medications with significant input from pharmacists.

At the age of 18 years, RX’s care was moved from paediatric to adult services. At the time, his paediatric care was excellent and his parents felt they were experts on their child’s condition and their opinions were always considered. However, no transition plan was put in place for RX and he was discharged from the paediatric service.

Under the paediatric service, RX’s health needs were the responsibility of one named paediatric consultant; however, he is now under the care of multiple adult care physicians but does not have a primary consultant or a named worker. This causes complications for both RX’s care and his medications. RX’s parents feel the move has been a rollercoaster of emotions, which has left them feeling both alone and unheard. They feel lost in the adult world and feel disengaged from RX’s care.

The table below highlights the issues within the case study that could have been avoided if a thorough transition plan had been in place for RX.

Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed[4], NICE[8], Australian Journal of Rural Health, Child: Care, health and development[9], Care Quality Commission[11]

Established transition programmes

While service provision is ad hoc in the UK, there are several established transition programmes, which have shown positive outcomes for young patients and their families:

1. ‘Ready Steady Go’ programme

Southampton Children’s Hospital has developed a resource, ‘Ready Steady Go’, which is a generic transition programme for patients aged 11 years and over[4]. The programme engages young people from the beginning of their transition journey through to their move to adult services and supports young people to manage their healthcare successfully in any adult service across the country[4]. The ‘Ready Steady Go’ programme has three questionnaires, which young people complete over their transition journey: 1) the getting ‘Ready’ questionnaire which is started at around the age of 11 years; 2) the ‘Steady’ questionnaire, which covers topics in greater depth at around age 13–14 years; 3) the ‘Go’ questionnaire which is started at around age 16 years to ensure that young people have all the skills and knowledge in place to ‘Go’ to adult services. The programme has been validated in the UK population and has been designed with the involvement of young people. This is a tool that could be used by the MDT to deliver a transition service[4].

2. 10 Steps Transition Pathway

Alder Hey Children’s Hospital has developed a 10 Steps Transition Pathway that describes the important steps for a young person, their parents and healthcare professionals as the young person moves to adult services[21]. Several different transition plan formats are in use at Alder Hey, including ‘Ready Steady Go’ and some condition-specific transition plans[21]. All young people at Alder Hey should have access to a handheld, personalised transition plan, which is commenced before their 15th birthday[21]. The young person should also have a circle of support identified — the people who are there to help the young person, including family / friends and healthcare professionals, in addition to a named worker. A pharmacist could be part of this circle of support.

3. Great Ormond Street Hospital

A transition workbook has been curated by the Great Ormond Street Hospital to aid the young person’s journey and to maintain engagement[22]. The workbook uses colours and shapes to help young people express their emotions, including their concerns and worries. In addition, each young person is expected to create a medication log to encourage them to be in charge of their own medication. At present, not all pharmacy team members are actively involved in this aspect of a patient’s journey; however, with more pharmacists taking on prescribing roles and carrying out clinics, this is a potential area for change.

Sources: Summary of product characteristics[23,24], BNF[25,26]

Additional resources:

- The Medicines for Children website has patient information leaflets on how to use medicines;

- Patient information leaflets (PILs) supplied with medications — however, pharmacists should be aware that often children and young people can be prescribed off-label or unlicensed medications, and therefore the use of a PIL is not always suitable;

- The Cystic Fibrosis Trust has a range of resources, including a transition booklet for young people with cystic fibrosis;

- The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has information online, including webinars and transition resources, which look at the transition experiences of patients and their families with links to specific conditions (e.g. asthma, epilepsy and HIV);

- Great Ormond Street Hospital ‘Growing up, gaining independence’ resource for patients and parents/carers;

- Advocacy group Together for Short Lives has created a planning tool for young people with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition, and their families.

Conclusion

A good transition experience should not be a challenge for young people and their families. Pharmacists are medicines experts and therefore should be an integral part of the transition experience. Transition is something that should be considered in everyday practice and, although the role of the pharmacist in transition is still emerging, pharmacists should aim to harness their skills and knowledge to proactively provide medication-related support and establish themselves as members of the transition MDT.

Acknowledgements

The following acknowledgement statement must be included in all publications which make reference to the ‘Ready Steady Go’ programme: ‘Ready Steady Go’ and ‘Hello to adult services’ were developed by the Transition Steering Group led by Arvind Nagra, paediatric nephrologist and clinical lead for transitional care at Southampton Children’s Hospital, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and are based on the work of S Whitehouse, MC Paone et al. and J.E. McDonagh et al.[14–16]. Further information can be found at www.uhs.nhs.uk/readysteadygo.

This article has been reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in June 2021.

- 1Key Data on Young People 2021. Youth Health Data. 2021.https://ayph-youthhealthdata.org.uk/key-data/ (accessed Aug 2023).

- 2‘Make Every Child Count’: Estimating current and future prevalence of children and young people with life-limiting conditions in the United Kingdom. Together for short lives. 2020.https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Prevalence-reportFinal_28_04_2020.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 3Hagell A, Shah R. Key data on young people 2021. Association for Young People’s Health. 2023.https://www.youngpeopleshealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AYPH_KDYP2019_FullVersion.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 4Nagra A, McGinnity PM, Davis N, et al. Implementing transition: Ready Steady Go. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2015;100:313–20. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-307423

- 5Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, et al. Current methods of transfer of young people with Type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet Med 2002;19:649–54. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00757.x

- 6Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, et al. Poor Prognosis of Young Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A longitudinal study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1052–7. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.4.1052

- 7Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatric Nephrology 2000;14:0469–72. doi:10.1007/s004670050794

- 8Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health and social care services. NICE guideline (NG43). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43 (accessed Aug 2023).

- 9Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Young people’s satisfaction of transitional care in adolescent rheumatology in the UK. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:368–79. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00698.x

- 10Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ 2012;344:e3718–e3718. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3718

- 11From the pond into the sea: children’s transition to adult health services. Care Quality Commission. 2014.http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/teenagers-complex-health-needs-lacksupport-they-approach-adulthood (accessed Aug 2023).

- 12Shaw KL, Watanabe A, Rankin E, et al. Walking the talk. Implementation of transitional care guidance in a UK paediatric and a neighbouring adult facility. Child Care Health Dev 2013;40:663–70. doi:10.1111/cch.12110

- 13Duguépéroux I, Tamalet A, Sermet-Gaudelus I, et al. Clinical Changes of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis during Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care. Journal of Adolescent Health 2008;43:459–65. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.005

- 14Whitehouse S, Paone M. Bridging the gap from youth to adulthood. Contemporary Pediatrics 1998;:13–16.

- 15Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC Model for Transitional Care of Adolescents. Prog Transpl 2006;16:291–302. doi:10.1177/152692480601600403

- 16McDonagh JE, Shaw KL, Southwood TR. Growing up and moving on in rheumatology: development and preliminary evaluation of a transitional care programme for a multicentre cohort of adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Child Health Care 2006;10:22–42. doi:10.1177/1367493506060203

- 17Trivedi A, Mohamad S, Sharma S, et al. Transition to adult services: the current and potential role of the UK hospital pharmacist. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2022;30:e70–5. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2022-003254

- 18Communicating with parents and involving children in medicines optimisation. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2017. doi:10.1211/pj.2017.20203683

- 19Hobart CB, Phan H. Pediatric-to-adult healthcare transitions: Current challenges and recommended practices. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2019;76:1544–54. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz165

- 20Mental Capacity Act. UK government. 2006.https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents (accessed Jul 2023).

- 2110 Steps Transition to Adult Services. Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust. 2021.https://alderhey.nhs.uk/services/transition-adult-services (accessed Jul 2023).

- 22Transition workbook. Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. 2021.https://media.gosh.nhs.uk/documents/SH-255-GOSH-booklet-FINAL.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 23Carbimazole 5mg tablets. Summary of product characteristics. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4267/smpc#gref (accessed Jun 2021).

- 24Propanolol 10mg tablets BP. Summary of product characteristics. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5888/smpc (accessed Jun 2021).

- 25Carbimazole. British National Formulary for Children. 2021.https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drug/carbimazole.html (accessed Jun 2021).

- 26Propranolol. British National Formulary for Children. 2021.https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drug/propranolol-hydrochloride.html (accessed Jun 2021).