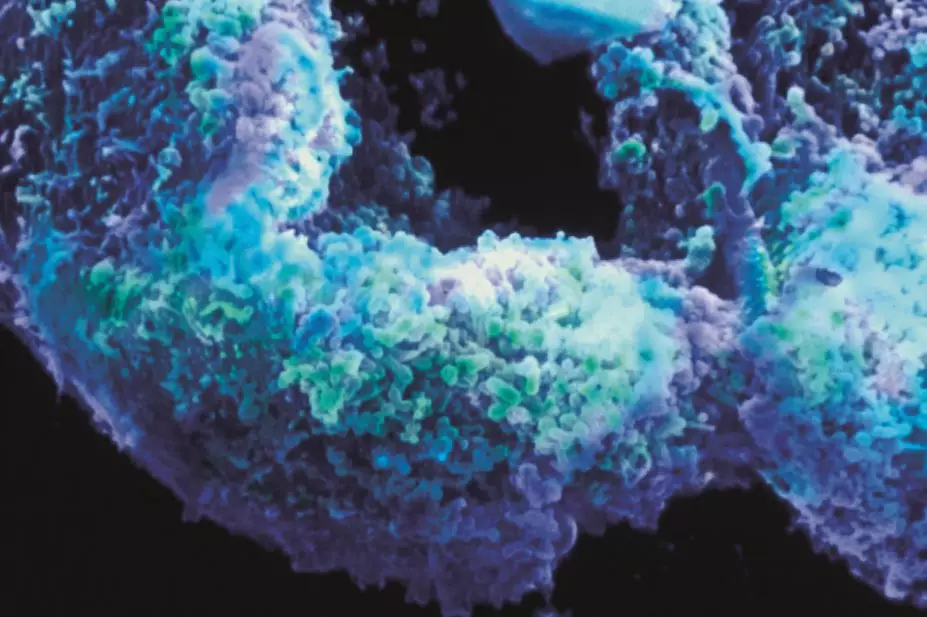

BSIP / Science Photo Library

Summary box

In this article you will learn:

- The most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections in the UK

- The treatment options for each bacterial sexually transmitted infection

- How antimicrobial resistance is affecting the treatment of bacterial sexually transmitted infections

Diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have increased considerably over the past decade, most notably in those aged under 25 years and men who have sex with men (MSM)[1]

. Although new STI diagnoses in England only increased slightly between 2012 and 2013 (from 446,253 to 448,775 diagnoses respectively), there was a marked increase in bacterial STI diagnoses, including gonorrhoea (15% increase), syphilis (9% increase) and chlamydia (7% increase). This rise in STI diagnoses is thought to be partly because of improved screening programmes. However, the data show that many people continue to have unsafe sex, putting themselves at risk.

Antibiotic resistance is another significant obstacle in the battle against STIs. Multi-drug resistant strains are more complex to treat, requiring test-of-cure follow-up and multi-drug regimens to ensure the infection is eradicated. Cases of untreatable gonorrhoea have already been reported[2]

, plus extensive reports of resistance to antibiotics in syphilis[3]

[4]

[5]

.

Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is a frequently asymptomatic bacterial infection of the genital tract. Reports suggest that 50% of men are asymptomatic while the proportion is higher in women at 70–80%[6]

. It is the most common STI in the UK, accounting for 47% (208,755) of all new diagnoses in 2013.

Acute symptoms include pain when urinating and abnormal vaginal or urethral discharge that is white, cloudy or colourless. In women, bleeding during or after sex is also a symptom. In addition, change in menstrual habit, such as bleeding between periods or heavier/lighter bleeding, are also symptoms.

Chlamydia is common in people with both high and low numbers of sexual partners. The Natsal-3 study found that 60% of women and 43% of men aged 16–44 years with chlamydia reported only one sexual partner in the previous year[7]

.

Although chlamydia is easily diagnosed with a swab or urine test, untreated infections can persist for months or years because of the infection’s often asymptomatic nature and cause a range of complications, particularly in women. Chlamydia can ascend the reproductive tract and cause pelvic inflammatory disease, a range of clinical disorders involving inflammation of the uterus, fallopian and ovarian tubes and the peritoneum, which can affect fertility.

The current recommended treatment options for chlamydia are:

- Azithromycin 1g orally as a single dose

- Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for seven days

The site of infection influences treatment, and it is important to perform pharyngeal and rectal swabs for sex workers or MSM. Pharyngeal chlamydia does not respond well to azithromycin and requires treatment with doxycycline.

Samples from patients with rectal chlamydia must be sent for typing, as the patient may have lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), a lymph node infection caused by invasive chlamydia serovars L1, L2, L2a or L3 that requires longer treatment[8]

.

Treatment options for LGV are:

- Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for 21 days

- Tetracycline 2g orally once a day for 21 days

- Minocycline 300mg as an initial oral dose then 200mg orally twice a day for 21 days

- Azithromycin 1g orally weekly for three weeks

- Erythromycin 500mg orally four times a day for 21 days.

Gonorrhoea

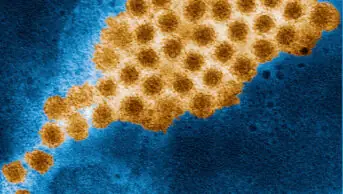

Gonorrhoea refers to an infection by the Gram-negative diplococcus Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infections usually occur in the mucus membranes of the urethra, endocervix, rectum, pharynx and conjunctiva. It is transmitted by direct contact with an infected membrane, and through vaginal, anal or oral sex. The signs and symptoms of gonorrhoea are similar to those of Chlamydia, except the vaginal or urethral discharge is thick and green or yellow in colour.

There is growing evidence of gonococcal resistance to several classes of antibiotics. Surveillance data for England and Wales in 2012 showed significant levels of N. gonorrhoeae resistance to penicillin (20% of tested samples), tetracyclines (69%) and ciprofloxacin (36%).

Because of these high rates of resistance, the current BASHH treatment guidelines[8]

are based on local sensitivity rather than historical evidence of efficacy.

The first-line treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhoea (infection that primarily affects the mucus membranes of urethra, endocervix, rectum, pharynx and conjunctiva) is a single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone 500mg plus a single dose of oral azithromycin 1g, or a single dose of oral cefixime 400mg plus oral azithromycin 1g if the intramuscular route is contraindicated[8]

.

Concomitant use of azithromycin is recommended by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) as it delays the onset of cephalosporin resistance and, in the case of pharyngeal gonorrhoea, aids eradication.

There have been reports that gonorrhoea strains H041 and F89 are resistant to both ceftriaxone and cefixime. In 2011, 6.3% of gonococcal isolates showed reduced susceptibility to cefixime, and three cases of treatment failure were reported in France[9]

and Canada[10]

. Consequently, the use of cefixime is only recommended if patients cannot receive intramuscular injections.

For patients in whom cephalosporins are contraindicated, such as those with penicillin allergy, a single dose of oral ciprofloxacin 500mg or oral ofloxacin 400mg can be used with a single dose of oral azithromycin 1g or intramuscular spectinomycin 2g. Spectinomycin is not licensed for this indication and not readily available, but is recommended by BASHH[8]

.

Syphilis

Syphilis is an infection with the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum; other treponemal diseases include bejel (mainly found in the Eastern Mediterranean and West Africa), pinta (mainly in Central and South America) and yaws (mainly found in tropical regions). It can be acquired or congenital, and is transmitted by direct contact with an infectious lesion.

Acquired syphilis is subdivided into primary, secondary, early latent, late latent and tertiary syphilis. Primary infection is characterised by a single painless ulcer (chancre), usually at the site of infection. Secondary syphilis manifestations include a skin rash, mucocutaneous lesions and lymphadenopathy; less common symptoms include patchy alopecia, anterior uveitis, meningitis, cranial nerve palsies, hepatitis, splenomegaly, periostitis and glomerulonephritis.

Patients with latent syphilis are usually asymptomatic and the infection is diagnosed by serological testing. It is classified as early latent syphilis if the patient is diagnosed within two years of infection; otherwise it is classified as late latent syphilis.

Symptomatic latent syphilis or tertiary syphilis is characterised by gummatous lesions (soft, non-cancerous granulomas characteristic of tertiary syphilis), cardiovascular and neurological complications.

Parenteral benzylpenicillin remains the treatment of choice for all stages of syphilis, however, the dose and duration depends upon the stage and clinical presentation (see ‘Treatment guidelines for syphilis’). Procaine benzylpenicillin is recommended as the first-line treatment for neurosyphilis.

There are extensive reports of T. pallidum resistance to macrolides, clindamycin and rifampicin, including localised reports of high rates of resistance; for example in 2004, 56% of syphilis cases in San Francisco were resistant to azithromycin[3]

[4]

[5]

.

Emerging resistance to tetracyclines — particularly doxycycline — is a major concern, but these antibiotics remain first-line alternative options for treating syphilis infections.

| Clinical stage | First-line treatment regimens | Alternative regimens |

|---|---|---|

Primary/secondary/early latent |

|

|

Late latent, cardiovascular and gummatous syphilis |

| |

Late latent neurosyphilis |

|

Screening programmes

Good sexual health is fundamental to the health and wellbeing of individuals. Sexual health needs vary according to factors including sexuality, age, gender and ethnicity, and some groups (for example, MSM, young people and sex workers) are disproportionately at risk of poor sexual health. Timely access to testing and treatment services can reduce the risk of onward STI transmission as well as supporting people to stay healthy and protected.

Strategies to increase testing include free and open access sexual health clinics, targeting people at higher risk of having STIs, and targeted or mass screening programmes. These include three-monthly tests for those who have had an STI and/or are at high risk for STIs; syphilis and HIV antenatal screening; integrating sexual health with reproductive health services; sexual health screening in prisons or drug services; and the national chlamydia screening programme in England. Health promotion and partner notification are also essential.

Pharmacists can improve sexual health provision by including discussions about STIs in consultations, for example when patients request emergency hormonal contraception, and signposting patients to appropriate screening services.

Lucy Hedley is a senior clinical pharmacist specialising in HIV/GUM & infectious diseases and Dereck Gondongwe MPharm is a rotational clinical pharmacist, both at University College London NHS Foundation Trust. Maryam Shahmanesh is a senior lecturer and honorary consultant (sexual health and HIV medicine) at the Research Department of Infection and Population Health, University College London.

References

[1] Public Health England. Infection Report. London: PHE 2014.

[2] Unemo M and Nicholas RA. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea. Future Microbiol 2012;7:1401–1422.

[3] Stamm LV. Global Challenge of Antibiotic-Resistant Treponema pallidum. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2010;54:583–589.

[4] Lukehart SA. Godornes C, Molini BJ et al. Macrolide Resistance in Treponema pallidum in the United States and Ireland. New Engl J Med 2004;351:154–158.

[5] Mitchell SJ, Engelman J, Kent CK et al. Azithromycin-resistant syphilis infection: San Francisco, California, 2000–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:337–345.

[6] Geisler WM, Wang C, Morrison SG et al. The natural history of untreated Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the interval between screening and returning for treatment. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:119–123.

[7] Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). The Lancet 2013;382:1795–1806.

[8] White J, O’Farrell N, & Daniels D. 2013 UK National Guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (CEG/BASHH) Guideline development group. Int J Std & Aids 2013. 24:593–601.

[9] Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R et al. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:1273–1280.

[10] Allen VG, Mitterni L, Seah C et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae treatment failure and susceptibility to cefixime in Toronto, Canada. JAMA 2013;309:163–170.

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control