Identify gaps in your knowledge:

1. How can people be helped to move through the stages in the “cycle of change”?

2. What is motivational interviewing?

3. How might pharmacists use motivational interviewing to support change? Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record,” (available at: www.rpsgb.org.uk/education). This article relates to “effects of lifestyle on health” and “health education and promotion” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

As pharmacists, we have all come across people who smoke, even though they (or their children) suffer from chronic asthma; people who are obese, even though they have diabetes; and people who do not exercise, even though they are overweight and suffer from hypertension. Quite rationally, many of us might wonder what is wrong with these people. Surely if a person’s behaviour is causing or exacerbating ill health, he or she would not behave in that way. Yet these people do continue harming themselves through their actions. More commonly, there are those who are not ill but keep an unhealthy lifestyle, despite being fully aware of the possible harmful consequences.

We all know that choosing a healthy lifestyle promotes our chances of good health. For example, stopping smoking reduces the risk of early death by some 25 per cent and taking sufficient exercise and avoiding obesity reduces our individual risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus by as much as 50 per cent. However, for many people, this means change and this is where the difficulties lie.

Our behaviours are strongly influenced by our values and beliefs, and change is difficult to bring about and to sustain. Change can create fear and anxiety. It is a complex internal process and the factors that create strongly held views (eg, “MMR vaccine is not safe”) and endorse beliefs and behaviours (eg,“I just have a very sweet tooth”) can be more subtle than they first appear. However, there now exists a compelling evidence-base to support adopting a healthier life style and public health policy in the United Kingdom is addressing this. Major initiatives such as health action zones that require health care professionals to work actively with individuals and communities to promote better health are in progress, and these provide opportunities for pharmacists to get involved.

Promoting change and knowing how to support it is an important skill for pharmacists. Not only does this promote good health, it can often affect the success of treatments. For example, if a smoker is prescribed a proton pump inhibitor it is less likely to cure an ulcer if he or she continues to smoke. Similarly, people with diabetes and who are obese will find their disease difficult to control, despite complying with their anti-diabetic medication.

The cycle of change

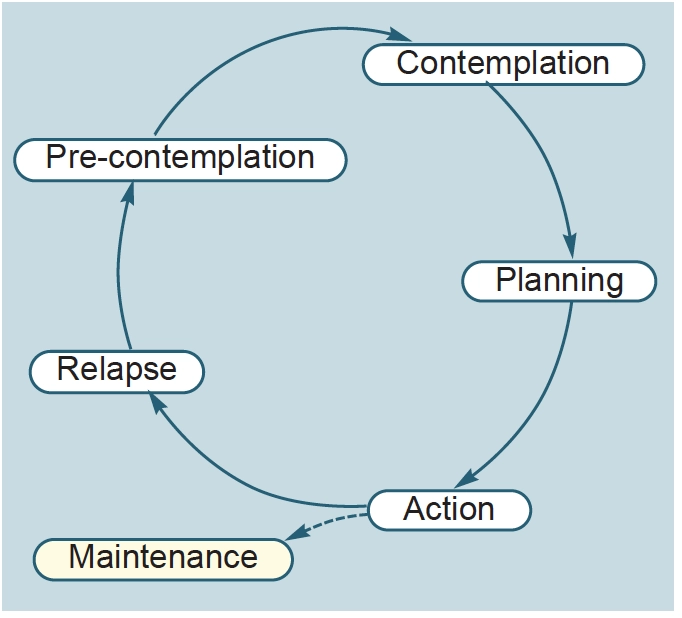

In order to support change effectively, we need to understand what the process involves. In the 1970s Prochaska and DiClimente1 developed the “cycle of change” as a conceptual model to explain how people change. This model is shown in Figure 1. The model identifies five stages of change and argues that behavioural change happens gradually, as people move through the cycle. If we learn to recognise what stage a person is at, we will be able to choose the most appropriate approach to use to counsel the individual.

Pre-contemplation

In the beginning, the individual is unwilling to change (or has never given it any serious thought) and is happy with his or her lifestyle. At this pre-contemplative stage he or she will be unreceptive to interference — “you’ve got to die sometime” is a common attitude.

Contemplation

When the person thinks about changing, but does not feel ready to — “I’d love to change but I just feel I can’t” — he or she is said to be at the contemplative stage of the cycle. He or she will be receptive to information and this is a good stage to provide health education, advice and encouragement to help move the individual to the next stage in the cycle.

Planning

At the third stage, a decision to change is made and the individual prepares for the change. For example, a date for change is set. Pharmacists could help in the preparation by asking the individual to identify family members or friends who are likely to provide good support and by talking about how to avoid situations that might lead to a relapse.

Action

The fourth stage of the cycle involves performing the change (eg, taking more exercise, eating less or stopping smoking). Here, individuals will need considerable support, encouragement and praise to help them through this vulnerable period. For example, someone with an alcohol problem who stops drinking is likely to become depressed and question if drinking is really that bad. However, as time passes, the change will become easier to maintain.

Relapse

People can move through the cycle a number of times before change is successful and this can be demotivating. It is important, therefore, to remind people that relapse is normal (and not to be seen as failure) and that the challenge is not to give up.

Motivational interviewing

Simply telling someone what to do often leads to failure. And when this happens pharmacists can stop trying — promoting change can be seen as a waste of time. However, if we accept that people are more likely to change if empowered to do so, this makes us interact with them in a different way and we will get better results.

The likelihood of an individual changing can be described by the term “cognitive dissonance”. This measures the difference between what a person does and what a person knows he or she should be doing. The larger the difference, the more likely it is that change will occur, in order to resolve the internal conflict. Cognitive dissonance can be brought about in a number of ways. Suffering a heart attack would be an extreme way of focusing attention on smoking, for example. Various campaigns (eg, against drinkdriving), can prompt cognitive dissonance. Health care professionals can also be effective in creating cognitive dissonance but if done incorrectly, this creates resistance to change because the individual attempts to justify the behaviour.

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centred model developed by Miller and Rollnick2. It creates “cognitive dissonance” without making the patient feel threatened or pressured. In addition to physical dependency, often there are social and emotional reasons that cause a person to continue with a behaviour. The aim of motivational interviewing is to help people explore what makes them do what they do and to allow them to come up with their own solutions to their own problems. It can be used at any time, but is probably most effective at the contemplation, planning or action stages of the change cycle. It is based on a philosophy that can be broken down to six elements and these are discussed below.

Resistance to change is typically a behaviour evoked by environmental conditions

Following the Vietnam war the United States planned for a huge heroin abuse problem within the veteran population. This did not happen because the environment that supported heroin use was not present when veterans returned to their families. In an appropriate environment, resistance can be overcome. In the pharmacy setting, this could mean creating a positive, nonjudgemental atmosphere, which could lead to the individual realising that change is needed. Motivational interviewing is confrontational in its purpose. It must increase an individual’s awareness of the problem and the need to change. However, an attempt to persuade people that they have a problem when they are unwilling or unready to accept it will lead to an argument. This should be avoided becausearguing increases resistance.

A classic strategy is to “roll with resistance”. Trying to convince a resistant individual to do something he or she does not want will only cause frustration and damage rapport. Instead, resistance should be identified and a different approach tried. For example, a person who tells you, “I really don’t like eating those types of foods”, in a conversation about healthy eating will probably stop listening if you go on about how they must eat five portions of fruit and vegetables every day. You could attempt to solve the problem by providing more information, or suggesting that they stop eating fried foods instead.

The client-counsellor relationship should be collaborative and friendly

In a collaborative environment people are more likely to open up and share their concerns. The individual needs to feel that we know where they are coming from. It is also important to empathise with the individual. Where a person’s views and opinions are respected and his or her difficulty with change appreciated, success is more likely. People who seem to be unwilling to change or are unco-operative are not necessarily being obstructive. This may merely be their way of dealing with the situation. We express empathy by asking open-ended questions and using reflective listening.

Priority is given to resolving ambivalence

When faced with a need to change people weigh up the pros and cons. Ambivalence is often the result of a poorly reasoned internal debate. Where the need for change is insufficiently strong, ambivalence wins and we stay where we are, sometimes indefinitely. Believing that change is necessary is at the heart of ensuring success. To eradicate ambivalence the individual must be motivated towards the desired behaviour. Persuasive strategies can fail because they can cause resistance — we all know the frustration of arguing with a committed smoker on the merits of stopping. However, motivation can be sparked when people see a discrepancy between where they are now and where they want to be in the future. Pharmacists can help the individual identify existing discrepancies through the use of open-questions. In this way, the individual, rather than the pharmacist, will come up with and reinforce the reason for change.

The counsellor does not prescribe specific methods or techniques

You can certainly educate people on the options open to them to achieve their goal but, ultimately, it is for the individual to choose his or her behaviour.

Just as people should be free to make choices they should be responsible for their progress

Although the counsellor can challenge and support people, he or she cannot assume responsibility for their progress.

There is a focus on the individual’s sense of self-efficacy

People must be able to feel that they can make a successful change in their lives. A major hurdle in successful change is the individual’s lack of belief that he or she can succeed. Understandably, if you weigh 22 stones getting to 18 stones is a major feat. Providing positive reinforcement is, therefore, vital. This is done by praising small achievements, endorsing efforts and getting the individual to focus on long-term goals.

Motivational interviewing in practice

In practice the essence of motivational interviewing is given in the mnemonic, OARS: open-ended questions, affirmations (positive statements), reflective listening (listening actively and using the person’s words to mirror what is said) and summaries (help to clarify what has been said). The following five open-ended questions can be asked in a motivational interview:

- “Tell me about the good things and the not so good things about. . .” Too often counsellors who do not use motivational interviewing put emphasis on change rather than the issues that will cause relapse when a change strategy is implemented. This question gets the individual to explore the positive and negative things about a behaviour. In motivational interviewing, negative terms (“bad things”) are not used because they are seen as judgemental and this sort of labelling increases resistance. The individual must be allowed to discuss the issue in a supportive and respectful environment, although clarification can be sought by using probing questions. In this way, rapport is built and suggestions made later in the interview will be more effective.

- “Tell me about a typical day in relation to . . .” This allows people to describe what a typical day is like from their perspective and to learn about themselves. For example, a person can list what they eat over 24 hours. This will provide information that can be used later.

- “What would you like to achieve?” This question is used to determine the individual’s priorities. For example, a person might be happy to get to 18 stones rather than a target weight of 12 stones. If we know this then we will understand why we might meet with resistance if we try to get the person to set what seems to them an unachievable target.

- “What do you need to know from me?” Although it can be difficult for practitioners trained to give advice, it is vital that up until this point no advice is given. The first three questions were to get information only. Now, information be can offered to allow the patient to understand health risks and the solutions to reducing those risks. The information provided should be objective and non-judgemental and motivate people towards change. Options for support can be considered, such as outlining the available types of services and local support groups. It is better if a number of options are given so that the person can make his or her choice.

- “So what are you going to do?” The previous questions gently steered the individual towards a change attempt (be it that day or much later) and this final question looks at the outcome. It gives the individual the responsibility of making a decision. In addition, the individual was to feel confident that this change is possible and you can help provide that motivation.

These open questions do not have to be asked in one intervention and could be asked over a few weeks. Motivational interviewing is commonly used in drug and alcohol centres and usually takes the form of one session each week. In contrast, pharmacists do not have this luxury. Unless you are trained as and paid to be a smoking cessation counsellor, the time available to spend with individuals is limited. However, OARS allows pharmacists to apply motivational interviewing principles in a brief interaction with an individual. During this time, the aim is to be focused on helping an individual think about his or her behaviour and move towards changing it.

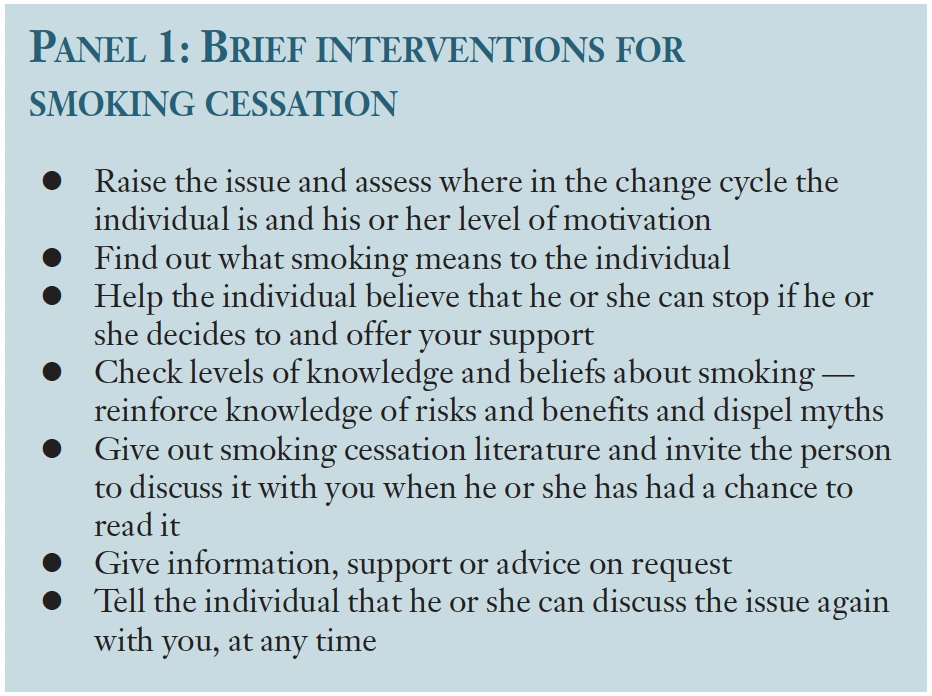

As an example, Panel 1 lists some brief interventions (along motivational interviewing principles) that can be performed in a pharmacy to help people to stop smoking.

Conclusion

Motivational interviewing is a powerful tool for effecting lifestyle change and is an essential skill for all health care professionals but it can be difficult to develop. Practising the strategies in this article will improve your skills. This should convince you of the value of the technique and you will help people make lasting healthy changes.

References

1. Prochaska J, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach: crossing traditional boundries of therapy. Homewood, Illinois: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984.

2. Miller, WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. New York: Guilford Press; 1991.