If medicines were celebrities, the gout treatment allopurinol (Zyloric) would never be on the “A” list for party invites. A low profile product for a historically embarrassing ailment, allopurinol is equivalent to the actor who is rarely out of work but is never the star. so it may come as a surprise that allopurinol emerged from a research programme that started at Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxosmithKline) in the early 1940s and, ultimately, gave its pioneering biochemists, Gertrude B Elion and George H Hitchings, a share of the 1988 nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology.

“Allopurinol is a drug which seems to have always been around. It undoubtedly reduces uric acid levels and prevents acute attacks of gout, but it’s never been used very well. It’s often prescribed in doses that are too low and patients don’t stay on treatment for long enough. Many are embarrassed about having gout because it’s still linked to drinking too much port or eating a rich diet,” explains Louise Warburton, shropshire GP with a special interest in rheumatology and musculoskeletal medicine, and president of the Primary Care Rheumatology (PCR) society.

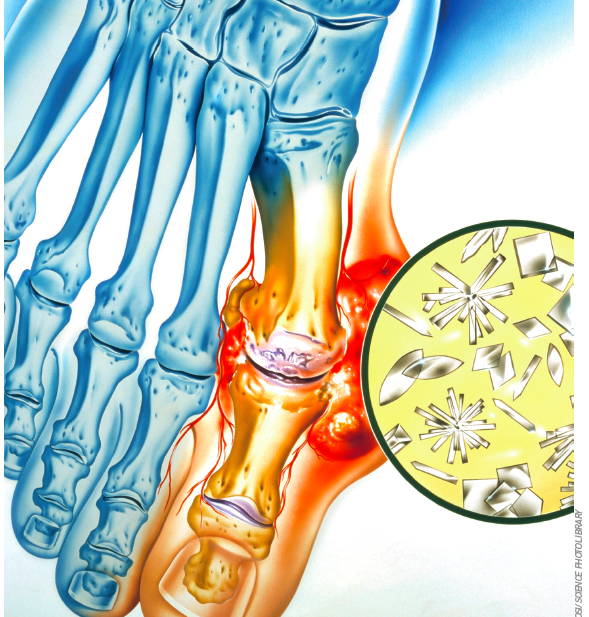

With gout on the increase1 and now considered the most common form of erosive arthropathy (ahead of rheumatoid arthritis), the PCR society has recently joined forces with the British society of Rheumatology (BsR) to press the national Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence to issue national guidelines on gout management. so allopurinol could well be in for a well deserved boost.

Dr Warburton points out that gout not only destroys joints and causes kidney damage, but is also associated with cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes. In addition, recent research has demonstrated that some antihypertensive drugs can increase the risk of gout while others, such as losaratan and calcium channel blockers, can reduce the risk, in line with their urate-lowering properties.2

“It’s not a condition to treat as a joke — a fat man’s disease caused by over-indulgence. It’s much more serious than that, but often poorly managed. We now need NICE clinical guidelines so that prompt intervention and better early management may decrease the risk of some patients developing resistant gout requiring costly interventions,” she says.

Untangling metabolic pathways

During the 1940s and 1950s, Elion and Hitchings were making purine compounds at Wellcome Research Laboratories in north Carolina, and testing them for their anticancer effects.3 One was 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), which is still used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.2 Digging further, Elion and Hitchings found that 6-MP was oxidised to 6-thiouric acid by the enzyme xanthine oxidase (XO), which was also responsible for converting hypoxanthine and xanthine into uric acid. Recognising the potential of XO-blocking agents in gout, they tested the hypoxanthine analogue, allopurinol, for its effects on serum and urinary uric acid.

Early studies showed that allopurinol did indeed block uric acid formation in gout patients. But there were concerns that longterm treatment could lead to a build up of xanthine, with the potential to form xanthine stones just as problematic as uric acid stones.3 Although xanthine stones were seen in dogs treated with high doses of allopurinol for long periods, they proved rare in humans because of differences in purine metabolism.3 Concerns that a build up of xanthine could potentiate XO formation, resulting in a need for increasing doses of allopurinol, also proved groundless, as did fears that allopurinol could potentiate tumour growth.2 In fact, it soon became clear that allopurinol had a role to play in cancer treatment as prophylactic therapy to prevent hyperuricaemia associated with cytotoxic drugs.

With safety concerns addressed and a growing body of clinical evidence that allopurinol was effective in preventing gout attacks and reducing tophi, the drug was in widespread clinical use by the mid-1960s.4,5

Dosing challenges

In early dose-ranging studies of allopurinol, 300mg–800mg/day were used to achieve uric acid reduction, with accompanying clinical improvement.3 But, given the era in which the drug was developed, it is unsurprising that placebo-controlled studies are lacking. The BSR recommends a starting dose of allopurinol of 50–100mg/day, increasing by 50–100mg increments every few weeks, adjusted if necessary for renal function, until a serum uric acid (SUA) level <300 μmol/L is reached, with a maximum recommended dose of 900mg/day.6 But primary care audit suggests that the vast majority of gout patients taking allopurinol are maintained on a 300mg daily dose, regardless of their SUA.7

“It’s only relatively recently that the BSR and the European League Against Rheumatism have recommended that patients should be treated to target uric acid levels, but this rarely happens. Many GPs are scared to increase the dose over 300mg, and don’t monitor their patients, some of whom need a higher dose of 400mg or 500mg,” says Dr Warburton.

Some prescribers may be deterred from increasing the dose of allopurinol because of concerns about adverse reactions, notably a rare but potentially fatal skin hypersensitivity reaction, which occurs in 0.01–0.1 per cent of cases.8 About 2 per cent of patients develop a rash while taking allopurinol,9 which requires discontinuation of treatment.8

Another problem is that some patients give up treatment because they initially feel worse, explains Dr Warburton: “Allopurinol can precipitate an attack of gout when the patient starts treatment, so it’s important also to prescribe a non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and/or colchicine prophylaxis for up to six weeks to get them through this period and keep them on treatment long enough for them to start seeing a benefit.”

She points out that successful prophylaxis with allopurinol should ensure that patients no longer get attacks of gout and, if they have tophi, these should disappear as the uric acid crystals dissolve and are excreted.

“It can take a couple of years to get rid of the tophi, after which patients need to stay on allopurinol indefinitely because their tendency to high uric acid levels doesn’t go away,” adds Dr Warburton.

A newer option

In 2008, a non-purine XO inhibitor, febuxostat, was approved by the European Medicines Agency. In a one-year, head-tohead study of gout prophylaxis published in the New England Journal of Medicine, febuxostat 80mg or 120mg/day was more effective than allopurinol 300mg/day in lowering serum urate, although similar reductions in gout flares and tophi size were seen with the two drugs.10 An accompanying editorial questioned whether febuxostat would have been better at lowering serum urate levels than allopurinol, if doses of the older drug could have been tailored to urate levels, rather than fixed at the most commonly used dose.11

In view of the higher cost of febuxostat compared with allopurinol, NICE recommends that it is only prescribed for people with chronic hyperuricaemia for whom allopurinol is contraindicated or who have experienced adverse effects severe enough to require discontinuation or prevent adequate dosing.12

“For the vast majority of patients who need gout prophylaxis, allopurinol is very effective and it’s cheap,” concludes Dr Warburton. “Allopurinol does what it says on the tin, but we need to be more careful in following the instructions on the label if we are to get the best out of it.”

References

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. The changing epidemiology of gout. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology 2007;3:443–9.

- Choi HK, Soriano LC, Zhang Y et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ 2012;344:d8190.

- Hitchings GH, Elion GB. Layer on layer: the Bruce F. Cain memorial Award lecture. Cancer Research 1985;45:2415–20.

- Rundles RW, Metz EN, Silberman HR. Allopurinol in the treatment of gout. Annals of Internal Medicine 1966;64:229–58.

- Rundles RW. Allopurinol. New England Journal of Medicine 1969;280:961.

- Jordan MM, Cameron JS, Snaith M et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatolgy guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2007;46:1372–4.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Concordance of the management of chronic gout in a UK primary-care population with the EULAR gout recommendations. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2007;66:1311–5.

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. SPC. Zyloric 100 mg, 300 mg. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed 29 February 2012).

- Neogi T. Gout. New England Journal of Medicine 2011;364:443–52.

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;353:2450–61.

- Moreland LW. Febuxostat — treatment for hyperuricemia and gout? New England Journal of Medicine 2005;353:2505–7.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hyperuricaemia — febuxostat (TA164), December 2008. Available at: guidance.nice.org.uk/TA164 (accessed 29 February 2012).