As athletes warm up for the start of the Olympic Games next week, it is unlikely that they will risk swallowing this month’s landmark drug — pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) — on the day of their event. The venerable nasal decongestant has been on and off international sporting blacklists over the past decade and is currently on the World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) prohibited list for use during competitions. As a result, athletes will jeopardise medals and future careers if they are found to have more than 150µg/ml of pseudoephedrine in their urine during the next few weeks.1

Thanks to its ready conversion into methamphetamine, pseudoephedrine is also subject to restrictions introduced in the UK in 2008 to make it a pharmacy medicine, reduce pack sizes and prevent sales of more than 720mg of the drug without a prescription. As a result, wholesale purchases of pseudoephedrine fell by 24 per cent between April 2010 and March 2011.2

Some governments have taken an even tougher stance, making pseudoephedrine-based products prescription only or introducing electronic tracking systems which require patients to provide personal information, retained for at least two years, when they purchase the drug.3

As a result of the growing restrictions on pseudoephedrine, some companies have replaced it with phenylephrine as a nasal decongestant as this cannot be converted to methamphetamine. But specialists, such as Ron Eccles, director of the Common Cold Centre at Cardiff University, believe this is a retrograde step for cold and rhinitis sufferers.

“Pseudoephedrine is a proven nasal decongestant, for which there is subjective and objective evidence that it reduces blockage, improves breathing and helps patients feel better. Phenylephrine nasal spray is an effective decongestant, but oral phenylephrine is rapidly metabolised in the gut and there is no evidence of efficacy,” he explains.

Chinese import

Pseudoephedrine treatment is thought to date back thousands of years, and Ephedra sinica — a Himalayan shrub from which ephedrine and its stereoisomer, pseudoephedrine, are derived — was recommended for use in colds, fever and asthma in an early Chinese pharmacopoeia.4

Successful chemical synthesis of pseudoephedrine was reported in the 1920s, although modern commercial production is by yeast fermentation of dextrose in the presence of benzaldehyde.

By the late 1950s, a number of oral formulations of pseudoephedrine were being marketed, and research was starting to suggest that pseudoephedrine was more useful as a nasal decongestant, via its alpha adrenergic vasoconstrictor activity in nasal mucosa, while ephedrine had superior bronchodilator activity via its beta-agonist effects in the airways.

Subsequent research in the 1970s further differentiated the two drugs on the basis of their potential for adverse cardiovascular effects, when it was shown that the dose of pseudoephedrine required to raise diastolic blood pressure above 90mmHg was three times higher than that of ephedrine.5 “Some people liked the stimulant effects of ephedrine, rather like a strong coffee, and it made them feel better. But there were concerns about the cardiovascular and central nervous system effects, so there was a gradual move towards pseudoephedrine in products for nasal congestion,” Professor Eccles explains.

In 1980, a study of pseudoephedrine was published which showed comparable effects of pseudoephedrine 60mg, 120mg and 180mg in reducing the effect of histamine on nasal airway resistance (NAR), all of which were significantly greater than with placebo (P< 0.05).6 Small, but statistically significant increases in pulse and systolic blood pressure occurred after pseudoephedrine 120mg and 180mg, but not after pseudoephedrine 60mg, 30mg or 15mg. So it was concluded that pseudoephedrine 60mg was the optimal single adult dose which achieved maximal nasal decongestion with minimal cardiovascular or other unwanted effects.

More recently, a large, placebo-controlled study of patients with nasal congestion associated with acute upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) showed significantly greater improvement in NAR following single and multiple doses of pseudoephedrine 60mg over three days, with accompanying subjective improvements.7

Pseudoephedrine is not totally free from stimulatory effects on the CNS: sleep disturbance and, rarely, hallucinations have been reported.8

Which combination?

Nasal congestion rarely occurs in isolation — in either allergic rhinitis or common cold sufferers. Antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids form the mainstay of treatment for allergic rhinitis, with intranasal steroids superior to antihistamines in relieving nasal blockage and most other symptoms.9 Allergy guidelines advise that use of topical decongestants, although more effective than oral agents, should be limited to less than 10 days, owing to potential for local irritation and drug-induced rhinitis.10 However, oral pseudoephedrine alone or combined with newer antihistamines has been shown to relieve nasal congestion in seasonal allergic and perennial rhinitis.11

In cold and influenza remedies, pseudoephedrine has been combined with a wide range of other agents, but an analgesic is almost universal — usually paracetamol.

The additive effect of paracetamol 1,000mg and pseudoephedrine 60mg has been demonstrated in a double blind study in URTI patients.12 Single and multiple doses of the combination provided a greater decongestant effect than either paracetamol or placebo and better pain relief than either pseudoephedrine or placebo.

Professor Eccles, one of the investigators in the study, explains that, although paracetamol caused slight worsening of nasal congestion, pseudoephedrine appeared slightly to enhance the analgesic effects of paracetamol.

“It makes sense to see pseudoephedrine enhancing the analgesic effects because of its slight stimulant properties, in the same way that caffeine can boost the effects of painkillers,” he explains.

Potential for abuse

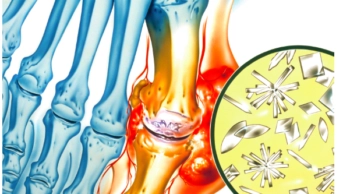

As all viewers of the cult US television series “Breaking bad” will know, methamphetamine is remarkably easy to make although producing highest quality crystals like those achieved in the programme by chemistry teacher turned drug baron Walter White requires considerable skill. As the latest “World drug report” points out, it is difficult to measure illicit manufacture and use of methamphetamine because of the small-scale, but widespread nature of production.13 As in previous years, the level of amphetamine abuse worldwide in 2010 came second only to cannabis, with estimates ranging from 14 million to 53 million users.13 Global methamphetamine seizures now exceed those of amphetamines, with increases in Central America and South and South East Asia, and criminal gangs operating increasingly through West Africa, in a way similar to cocaine traffickers.13

The widespread limitations introduced on sales of pseudoephedrine followed an increase in methamphetamine use in the US, UK and elsewhere during the early 2000s. But the latest UK Public Assessment Report from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency makes reassuring reading.2 As well as documenting a reduction in pseudoephedrine sales since restrictions were introduced on the amount that can be purchased, the report notes the lack of evidence of widespread methamphetamine use in the UK.2 Professor Eccles points out that the biggest problems are focused on the larger drug factories in Mexico and some US states but believes that some of the media coverage have a political rather than a medical basis.

“Of course it’s tragic when someone dies as a result of substance abuse, but it’s often difficult to know what they were taking. In the US, you see politicians talking about the risks of pseudoephedrine without really knowing the facts and, as a result, we are seeing pseudoephedrine being replaced with phenylephrine in oral products when there really is no good evidence of efficacy,” he says.

Use in sport

For Olympic athletes, the advice about taking oral products containing pseudoephedrine is clear-cut. WADA advises them to stop taking such products 24 hours before in-competition periods. Some experts question the need for pseudoephedrine to be on the banned list at all. It was off the banned list altogether from 2004–09. One recent placebo-controlled study of the effects of pseudoephedrine 2.5mg/kg body weight on the performance of female college athletes failed to show any impact on 800 metre run times.14 But a similar study carried out in 1,500 metre runners did show a 2 per cent reduction in completion time.15

Professor Eccles suggests that the restriction is less to do with performance enhancement and more to do with potential drug test confusion with other substances with similar structures, such as ephedrine and methamphetamine. He concludes that pseudoephedrine is a tough product to challenge as a nasal decongestant.

“In my 40 years in the business, I’ve seen companies spend a lot of money trying to develop new decongestants, but it always come back to safety. You can get efficacy, but when you’re selling in a consumer market, you have to be sure that the vasoconstrictor effects you need for the decongestant aren’t going to cause safety problems elsewhere, such as the kidney. Only pseudoephedrine has been able to strike the right balance and, given that it’s available in multi-symptom products in the oral formulations that patients like, I can’t see it being bettered. Any action to take account of the methamphetamine issue should be proportional, otherwise we will be depriving the general public of a safe and effective oral decongestant.”

References

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Prohibited list 2012. Available at www.wada-ama.org (accessed 13 July 2012).

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. UK public assessment report. Pseudoephedrine- and ephedrine-containing medicines: 2011 review of actions to manage the risk of misuse August 2011. Available at www.mhra.gov.uk (accessed 13 July 2012).

- Eccles R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongestant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2007;63:10–4.

- Ravina E. The evolution of drug discovery: from traditional medicines to modern drugs. Germany: Wiley VCH; 2011.

- Drew CD, Knight GT, Hughes DT et al. Comparison of the effects of D-(-)-ephedrine and L-(+)-pseudoephedrine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in man. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1978;6:221–5.

- Empey DW, Young GA, Letley E et al. Dose-response study of the nasal decongestant and cardiovascular effects of pseudoephedrine. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1980;9:351–8.

- Eccles R, Jawad MS, Jawad SS et al. Efficacy and safety of single and multiple doses of pseudoephedrine in the treatment of nasal congestion associated with common cold. American Journal Rhinology 2005;19:25–31.

- E-Medicines Compendium. Sudafed decongestant tablets. Available at: www.medicines.org.uk (accessed 13 July 2012).

- Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, Puy RM. Intranasal corticosteroids versus oral H1 receptor antagonists in allergic rhinitis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1998;317:1624–9.

- van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C, Passalacqua G, et al. Consensus statement on the treatment of allergic rhinitis. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2000;55:116–34.

- Meltzer EO, Caballero F, Fromer LM et al. Treatment of congestion in upper respiratory diseases. International Journal of General Medicine 2010;3:69–91.

- Eccles R, Jawad M, Jawad S et al. Efficacy of a paracetamol-pseudoephedrine combination for treatment of nasal congestion and pain-related symptoms in upper respiratory tract infection. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2006;22:2411–8.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2012.

- Berry C, Wagner DR. Effect of Pseudoephedrine on 800 M run times of female collegiate track athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 29 November 2011 [Epub ahead of print].

- Hodges K, Hancock S, Currell K et al. Pseudoephedrine enhances performance in 1500-m runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2006;38:329–33.