Jochen Tack / Alamy

A naturally occurring antioxidant — 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (7,8-DHF) — found in tree leaves, cherries and soybeans, mimics brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a hormone secreted after physical exercise that controls weight gain.

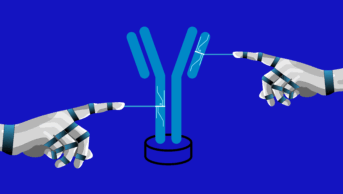

Manipulation of the signalling elicited by BDNF, which suppresses food intake and enhances energy expenditure, represents a promising strategy for combatting obesity; however, BDNF degrades quickly in the body.

Using a mouse model of diet-induced obesity (DIO) and a specific knockout mouse, scientists have shown that the flavonoid 7,8-DHF works better than BDNF in firing TrkB (Tropomysin receptor kinase B), one of BDNF’s receptors that triggers fat metabolism. The study was published in Chemistry and Biology

[1]

on 5 March 2015.

After a long hunt for a chemical that mimics BDNF, the team, led by Keqiang Ye from the Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, arrived at 7,8-DHF.

“We initiated a cell-based drug screening to identify this small molecule that selectively binds TrkB receptor and imitates the physiological functions of BDNF,” says Ye.

TrkB is a receptor protein that is found mainly in the brain, but also in peripheral tissues like the lungs and skeletal muscles in low concentrations. During physical exercise, excess BDNF is secreted and it is transported via blood platelets to TrkB, where AMP-kinase mediated fat-burning begins. But BDNF is short-lived and cannot be supplied to TrkB continuously.

Using muscle-specific TrkB knockout (MTKO) mice, the authors show that 7,8-DHF activates TrkB in skeletal muscles, but not TrkB present elsewhere, for example in the central nervous system. By feeding the DIO mouse orally for 20 days along with a high-fat diet, the researchers prove that the flavonoid can “chronically activate” TrkB to burn body fat and maintain weight.

7,8-DHF can cross the blood-brain barrier and has double the half-life in blood compared with BDNF, says Ye. But the researchers had to feed the mice with 7,8-DHF for a long time before they observed its stable anti-obesity effect.

“The key [here is] to easily burn the fat without suffering through stern physical exercise to produce BDNF in muscle,” says Ye.

7,8-DHF had no effect in male mice. Ye has no firm explanation for this gender-specific action. “It is possible that oestrogen may regulate flavonoid metabolism to distinguish females from males,” he says.

Since 7,8-DHF is found in vegetables, fruits and other foods, a question arises as to whether it needs to be developed as a drug. “To eat the food may not help much,” says Ye. “Simply because of the low dose.” Instead, Ye is developing an oral dietary supplement – a prodrug that can make and maintain 7,8-DHF in the blood and brain.

Ye’s team has filed a patent on 7,8-DHF and has started an IND (Investigational New Drug) trial and a pre-clinical trial in Alzheimer’s disease, since they previously found 7,8-DHF to have neurologic effects. “[If these trials] are successful, we plan to initiate the anti-obesity trial,” says Ye. “The promising efficacy and safety for this drug make us confident that the market will be huge [for it as an] anti-obesity drug”.