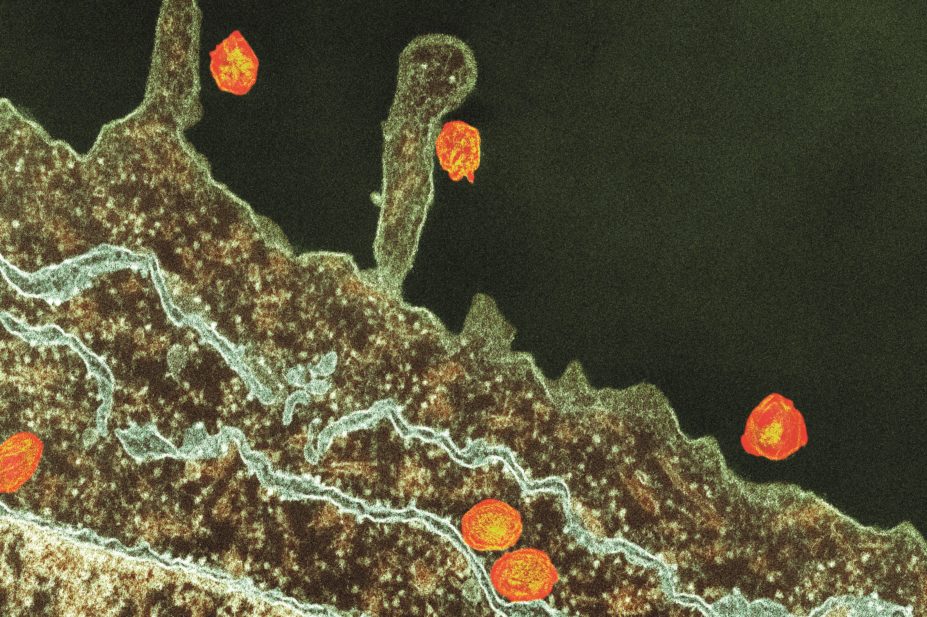

Thomas Deerinck, NCMIR / Science Photo Library

Community pharmacists have the potential to screen at-risk groups for hepatitis C and could play a key role in helping to improve liver disease services in primary care, according to the conclusions of a commission set up to investigate the impact of the disease.

Writing in The Lancet (online, 27 November 2014)[1]

, the group of leading doctors and medical scientists who made up the commission argue that screening for hepatitis C in primary care is cost-effective.

People at risk of the disease could be screened in community pharmacies that already offer needle exchange or methadone services, suggests the group, led by Roger Williams, director of the institute of hepatology at Foundation for Liver Research, London.

There is a need, they argue, to seek non-traditional primary care settings to help identify those people at risk of liver disease who are not picked up by other services.

The group of experts also predict that the development of new drugs for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis means that “substantial grounds exist for optimism, even to the extent of being able to contemplate eradication of both hepatitis B and C within two to three decades”.

They point out that drugs for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection have improved so much that treatment is nearly 100% effective in controlling progression of liver disease. “New drugs being introduced for hepatitis C infection are revolutionary because they are more effective in viral clearance, need shorter periods of treatment, and have fewer side effects than do previous drug treatments,” the experts write.

The group says that current barriers towards achieving eradication include the “unrecognised substantial pools of people infected with hepatitis C or hepatitis B in the community and the underutilisation of vaccines against hepatitis B”.

The suggestion to increase the role of community pharmacists in liver disease reflects two of the commission’s ten overarching recommendations – to strengthen the detection and treatment of early liver disease by boosting the clinical expertise of those working in primary care, and to improve support services in the community setting for screening high-risk patients.

The commission also wants to see every district general hospital in the UK have its own acute liver unit and a national network of 30 specialist liver disease centres established across the UK to help create equal access to services.

The group of experts say the UK is the only country in western Europe — apart from Finland — that has seen an increase in liver disease in the past 30 years.

Sarah Knighton, pharmacy team leader for liver disease at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, welcomed the recommendations to increase the role of community pharmacists in screening patients and the establishment of an acute liver unit in every district hospital supported by a network of specialist centres.

“It is a postcode lottery at the moment if you get referred or if you get referred to the right person or the right service at the right time, so having a national network would be great,” she says. “The idea of community pharmacists offering hepatitis testing isn’t new. Some have been involved in pilots taking blood spot tests to assess whether any patients have hepatitis C antibodies who can then be referred on to appropriate pathways.”

Knighton supports the expansion of these services and says results from the pilots have been positive. “If you are on methadone you would be seeing your community pharmacist every day. You will have built up a good relationship and may feel more comfortable discussing these issues with them.”

Knighton agrees there has been huge progress in the development of drugs to treat viral hepatitis, which can have cure rates of between 90% and 100%. “The issue is how to fund the drugs and also how people can access them,” she adds.

References

[1] Williams R, Aspinall R, Bellis M et al. Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis. The Lancet 2014. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61838-9