Universal Images Group Limited / Alamy Stock Photo

All patients at high risk of heart disease including those with normal blood pressure should be considered eligible for blood pressure-lowering drugs, new research suggests.

Findings from a meta-analysis published in The Lancet[1]

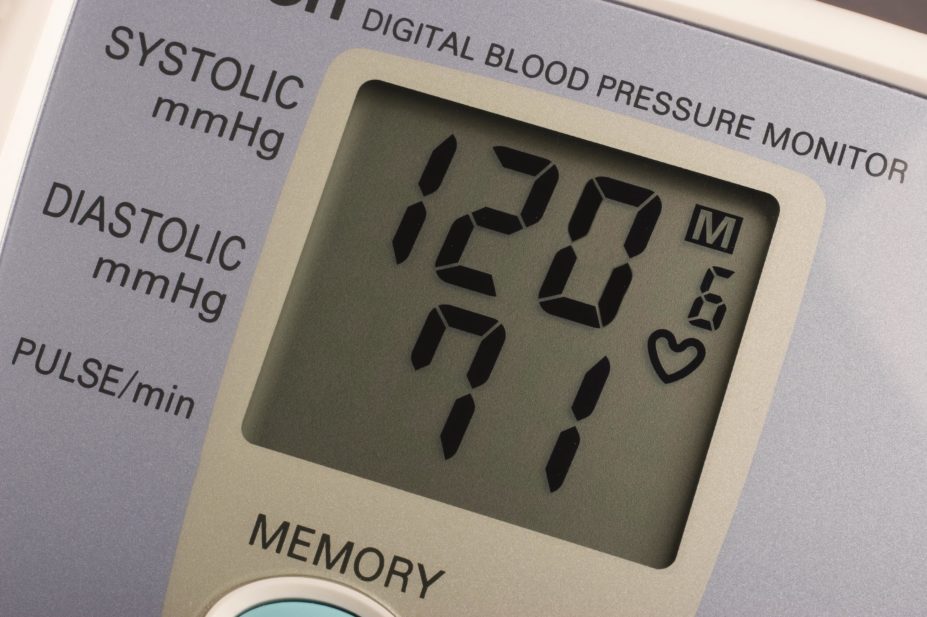

on 24 December 2015 show that lowering systolic blood pressure to less than 130mmHg benefits patients, and the study’s authors recommend that those with a history of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, heart failure or chronic kidney disease should be offered blood pressure-lowering treatment.

“Blood pressure-lowering drugs should not be thought of as agents for use in people with ‘hypertension’ only,” says lead researcher Kazem Rahimi, a cardiologist at the University of Oxford. “Our study suggests that a 10mmHg reduction in blood pressure confers the same relative reduction in risk of cardiovascular events among those who have high or low blood pressure.”

Worldwide, hypertension is the most important risk factor for death and disability, yet it remains unclear whether blood pressure-lowering treatment reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease in all patient populations. This study combined data from large-scale blood pressure-lowering trials published between 1966 and 2015 to quantify the effects of reduced blood pressure on cardiovascular outcomes and death.

The researchers analysed data from 613,815 participants across 123 studies, and found that a 10mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure reduced the risk of major cardiovascular disease events by 20%, the risk of coronary heart disease by 17%, stroke by 27%, heart failure by 28%, and all-cause mortality by 13%.

“All major classes of drugs were effective at reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease,” says Rahimi. “However, despite their general efficacy, there were some significant differences among them in the reduction of risk of specific clinical outcomes.” Calcium channel blockers seemed to be more effective than other classes of drugs for stroke prevention, and diuretics were more effective for prevention of heart failure, the researchers found.

“The findings call for blood pressure lowering based on an individual’s potential net benefit from treatment rather than treatment to a specific target,” conclude the researchers.

In an accompanying comment piece[2]

by Stéphane Laurent and Pierre Boutouyrie, two pharmacologists from France’s national medical research agency INSERM, say the findings relating to specific drug classes support the results of previous studies and extend the evidence available for drugs to be used preferentially in specific conditions. “However, the present meta-analysis cannot determine the resulting effect of combinations of drug treatments that are increasingly prescribed in routine clinical practice.”

The meta-analysis extends the initial findings of the landmark Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT)[3]

, sponsored by the US National Institute of Health and published in 2015, which found that achieving a systolic blood pressure of 120mmHg — rather than 140 mmHg — reduces rates of cardiovascular events by a third and rates of death by a quarter in hypertensive patients aged 50 years and older.

Lead cardiac pharmacist Paul Wright of Barts Health NHS Trust in London says the study “gives confidence in the recent SPRINT trial, suggesting that lower blood pressure is better”.

Wright says that adverse events can be expected with tighter treatment targets but says the meta-analysis will support lower treatment targets for many national guidelines on the clinical management of blood pressure.

References

[1] Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A et al Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 2015 DOI: 10.1016/SO140-6736(15)01225-8

[2] Laurent S and Boutouyrie P. Blood pressure lowering trials: wrapping up the topic? The Lancet 2015 DOI: 10.1016/SO140-6736(15)01344-6

[3] Wright JTJ, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. 2015 New England Journal of Medicine 373: 2103–16. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939