Shutterstock.com

GPs should conduct a C-reactive protein (CRP) test to determine whether a patient should be treated with antibiotics if it is unclear whether they have pneumonia, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) says.

NICE’s first guideline

[1]

on the diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults is aimed at helping GPs and hospital doctors follow the principles of antimicrobial stewardship so they only prescribe antibiotics when necessary.

Patients who need antibiotics should be prescribed them as early as possible, according to Mark Baker, NICE’s director of clinical practice. “Accurate assessment of respiratory infections like pneumonia allows healthcare professionals to prescribe treatments responsibly,” he says. “This both reduces costs and any potential harm from over-exposure to antibiotics.”

The guideline recommends that if a diagnosis of pneumonia has not been made after clinical assessment and it is unclear whether antibiotics should be prescribed, GPs should consider a CRP test. This simple point-of-care blood test can provide an assessment of inflammation in the body within minutes, and high CRP levels suggest an infection is bacterial.

NICE recommends that antibiotics should be prescribed if the CRP concentration is greater than 100 mg/litre. A delayed prescription (a prescription for use at a later date if symptoms worsen) should be considered if the CRP concentration is between 20 mg/litre and 100 mg/litre, and antibiotics should not be offered routinely if the CRP concentration is less than 20 mg/litre.

“If it was not particularly clear whether a patient had pneumonia or not, the CRP test might give a bit more information for the GP to determine whether it is likely to be pneumonia or significant infection that needs antibiotics, or a more mild lower respiratory tract infection or viral infection where antibiotics aren’t indicated,” says Toby Capstick, lead respiratory pharmacist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and joint chair of the United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association respiratory group. “Potentially it could reduce inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in primary care.”

Maureen Baker, chair of the Royal College of GPs, says the CRP test is a valuable tool that GP practices might find helpful in making decisions about whether to prescribe antibiotics, but she stressed that it is an “indicative test and what we really need is a definitive test”.

“We need more research into developing a more dependable – yet affordable – test, as well as the urgent development of new antibiotics to protect the public against emerging bacterial infections and diseases in the future,” she says.

The NICE guideline also includes recommendations on the type of antibiotics to offer depending on how severe a person’s pneumonia is. Low severity pneumonia should be treated with a shorter five-day course of a single antibiotic instead of the standard seven-day course. Patients with low-severity community-acquired pneumonia should not be prescribed either a fluoroquinolone or dual antibiotic therapy routinely.

To help reduce anxiety and avoid unnecessary appointments, patients treated for pneumonia should be told that symptoms should steadily improve after starting treatment but that it may take up to six months to feel back to normal, NICE says.

NICE says up to 480,000 adults develop pneumonia each year in the UK. It is diagnosed in 5–12% of adults who present to GPs with symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, and 22–42% of these are admitted to hospital, where the mortality rate is between 5% and 14%. Between 1.2% and 10% of adults admitted to hospital with community-acquired pneumonia are managed in an intensive care unit, and for these patients the risk of dying is more than 30%, according to the guideline.

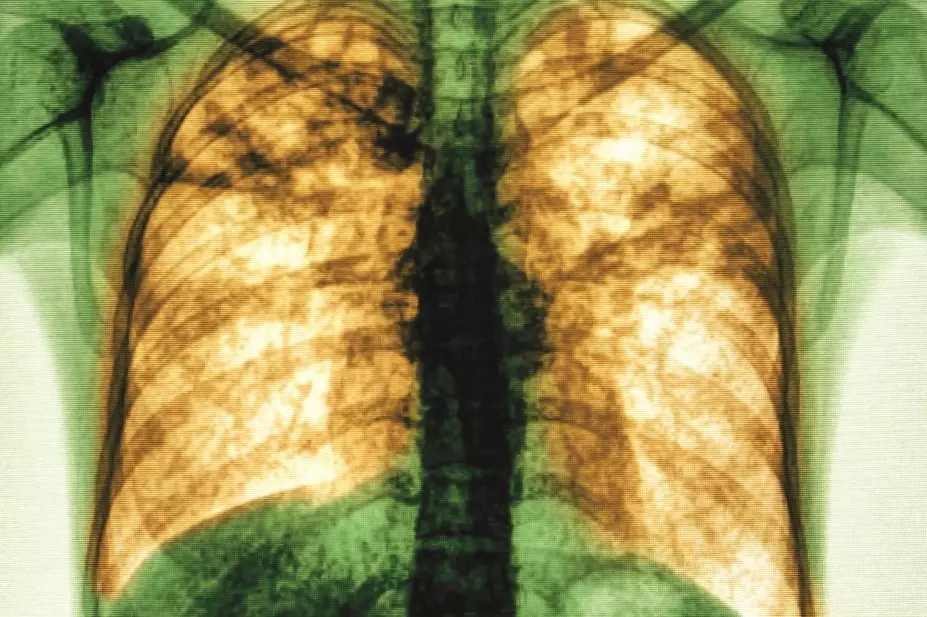

NICE recommends that GPs use a risk assessment tool, either the CRB65 or CURB65 score based on factors including age and presence of certain symptoms (confusion, raised respiratory rate, low blood pressure), to determine whether patients are at low, intermediate, or high risk of death and whether they need to be admitted to hospital. In hospital, diagnosis (including X-rays) and treatment of pneumonia should take place within four hours of admission.

Hospital staff should consider measuring baseline CRP concentration in patients with community-acquired pneumonia on admission to hospital, and repeat the test if clinical progress is uncertain after 48-72 hours. NICE says research is needed to determine whether CRP monitoring can be used in addition to clinical observation to guide antibiotic duration in patients hospitalised with moderate- to high-severity community-acquired pneumonia in order to safely reduce the total duration of therapy.