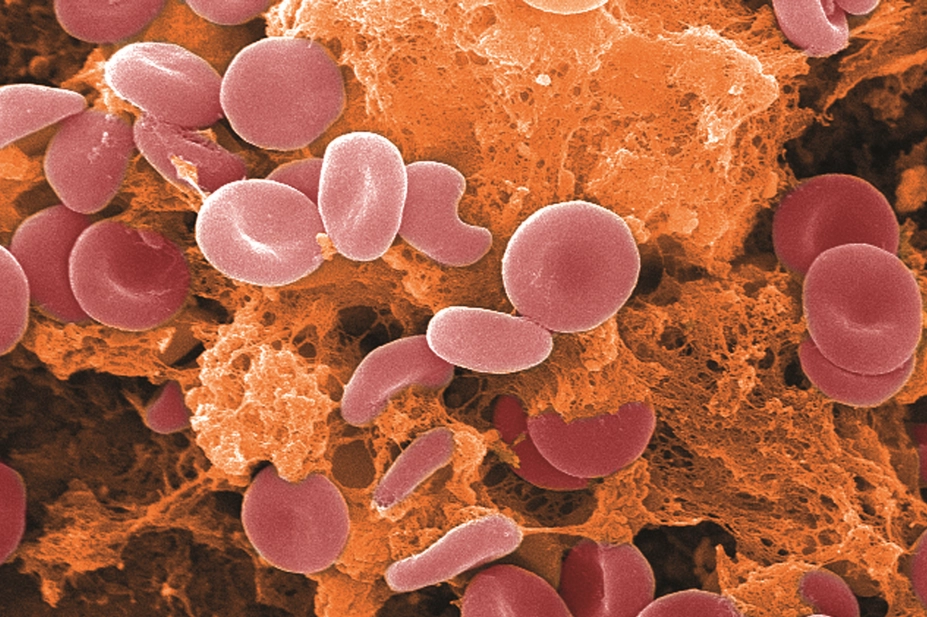

Scott Camazine / Alamy Stock Photo

Testosterone treatment is associated with an increased risk of serious blood clots, according to the results of an observational study of almost 1 million UK men.

Researchers analysed records from 370 general practices in UK primary care involving 19,215 patients with venous thromboembolism, comprising deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and compared them with 909,530 matched controls.

The team found the increased risk of venous thromboembolism peaks within the first six months of taking the hormone before dropping off again.

The researchers split the patients into those who had recently had testosterone treatment but were not taking it currently; those who were currently on testosterone treatment for either more than six months or less than six months; and those who had not had any treatment for two years.

The researchers found a 25% increased risk of venous thromboembolism for those currently on treatment compared with those not taking testosterone.

The highest risk was found in those who were less than six months into treatment, with a 63% increased chance of a clot compared with those who had not used testosterone.

The findings, however, only equate to an extra ten cases of venous thromboembolism per 10,000 person years in men who have just started taking testosterone over the general rate of 15.8 blood clots per 10,000 person years, the researchers said.

Reporting in The BMJ

[1]

(online, 30 November 2016), the researchers say the transient nature of the increased risk could explain why previous studies have reported contradictory results.

There has been a striking increase in the prescribing of testosterone in the past decade with a ten-fold increase in the United States. Much of this is for “unclear and questionable indications”, the researchers say, including sexual dysfunction and low energy.

Richard Quinton, a member of the Society for Endocrinology and consultant endocrinologist at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, says: “In the [past decade], most men being prescribed testosterone would have had organic hypogonadism, whereas in the later years a greater proportion would be receiving it for vague symptoms relating to obesity and sexual dysfunction.

“It would be very useful to know whether venous thromboembolism risk was lower in the first half of the decade they studied compared to the second.”

In June 2014, regulators in Canada and the United States added general warnings in the drug labelling of all approved testosterone products about the risk of venous thromboembolism, but the evidence has been mixed with studies.

The researchers say that the risk associated with testosterone treatment is comparable to that seen in women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill or oestrogen replacement therapy for menopause.

They say the reason for the increase is not totally clear but it is separate from other increased risks of cardiovascular events in middle aged and older men taking testosterone.

“Future research is needed to confirm this temporal increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism and to investigate the risk in first time testosterone users and confirm the absence of risk with long-term use,” the team concludes.

References

[1] Martinez C, Suissa S, Rietbrock S et al. Testosterone treatment and risk of venous thromboembolism: population based case-control study. BMJ 2016;355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5968