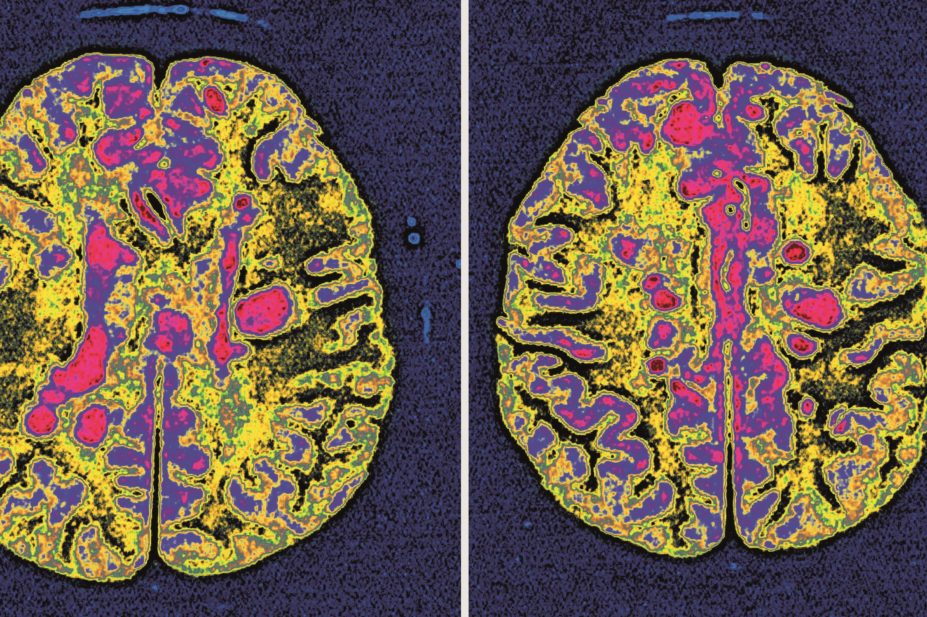

BSIP SA / Alamy

Treatment with interferon beta or glatiramer acetate reduces disability progression by 24-40% in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published in The

Lancet Neurology

[1]

on 1 April 2015.

The two drugs were found to be cost-effective when data from the UK’s multiple sclerosis risk sharing scheme were modelled over 20 years.

“Our findings support the continued commissioning of these disease-modifying therapies by healthcare providers,” say the authors of the study, led by Jacqueline Palace, of the department of clinical neurology, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust.

In 2002, the then National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) concluded that interferon beta and glatiramer acetate would be cost effective as disease-modifying therapies for MS only if the short-term disability benefits reported in clinical trials were maintained. As a result, a risk-sharing scheme was established to assess whether the effects on disability progression of these therapies met NICE’s cost-effectiveness target of £36,000 per quality-adjusted life-year projected over 20 years.

The study assessed the cost-effectiveness of glatiramer acetate, interferon beta-1b, and two formulations of interferon beta-1a at six years. The researchers compared disability progression in 4,137 patients with relapsing-remitting MS enrolled in the UK’s MS risk-sharing scheme with progression of untreated patients, determined by modelling data from 898 patients in British Columbia, Canada, who met the same eligibility criteria. Patients enrolled in the UK scheme had been followed up for an average of 5.1 years.

Two measures – the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score and utility (a measure based on EDSS scores and quality of life) – were used to assess disability progression using two statistical models (the Markov model and multilevel model). An EDSS ratio (treated versus untreated patients) of less than 100% implied that progression on treatment was slower than expected progression without treatment, while a utility ratio of 62% or less (i.e. a minimum 38% reduction) indicated cost-effectiveness.

Using both statistical models, patients in the risk-sharing scheme showed slower EDSS progression than predicted for untreated controls (Markov model, 75.8% [95% confidence interval [CI] 71.4–80.2]; multilevel model, 60.0% [95% CI 56.6–63.4]) equivalent to a 24% and 40% relative reduction in progression, respectively. And utility ratios were consistent with cost-effectiveness (Markov model, 58.5% [95% CI 54.2–62.8]; multilevel model, 57.1% [95% CI 53.0–61.2]).

“Ensuring the cost-effectiveness of increasingly expensive drugs is becoming imperative,” say the researchers, who point out that managed-entry and risk-sharing agreements between commissioners and manufacturers are increasingly used to deliver value for money with new and expensive therapies.

“The application of prognostic models supports the use of this type of scheme for other chronic diseases for which long-term trials are not thought appropriate,” the researchers add.

Just 40% of people eligible for disease-modifying therapies in the UK are accessing them, which is one of the lowest rates in Europe, according to Sally Hughes, programme director for policy and external relations at the MS Society.

“This is robust evidence that shows these treatments slow disability and, crucially, can be provided on the NHS at a cost-effective price – the results provide an important cornerstone for the future of MS treatment and related prescribing policy,” she says. “It is essential that these treatments continue to be provided on the NHS once the scheme stops collecting data this summer.”

When the first preliminary data from the MS risk-sharing scheme were published in 2013, NICE announced that it would review its guidance on the use of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS in 2015. This will “allow incorporation of mature data from the risk-sharing scheme”, according to a NICE spokesperson.

- This article was amended on 29 April 2015 to clarify that the observed effect size was calculated for treated patients not for individual therapies.

References

[1] Palace J, Duddy M, Bregenzer T et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the UK Multiple Sclerosis Risk Sharing Scheme at 6 years: a clinical cohort study with natural history comparator. Lancet Neurology 2015;14:497–505. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00018-6.