Introduction

Patient access schemes (PASs), sometimes referred to as risk-sharing schemes or market access schemes, allow pharmaceutical companies to offer discounts or rebates to reduce the cost of a drug to the NHS. They are regarded as a way of improving access to new medicines for NHS patients.

Drug pricing is complex and is controlled in the UK by the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme. The 2009 PPRS[1]

recognises that PASs have some value in improving cost-effectiveness to enable National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence approval but states that access schemes should be the exception rather than the rule. In oncology, however, the use of schemes for new medicines seems to be becoming the norm.

The 2009 PPRS maintained the Government’s balancing act between ensuring value for money for the NHS and maintaining a profitable pharmaceutical industry by providing mechanisms to encourage the uptake of innovative medicines. It has also been suggested that the PPRS is an important component of UK Government policy towards the pharmaceutical industry — that is, as a means of attracting and retaining pharmaceutical R&D and other internationally mobile investments within the UK.[2]

Schemes can be submitted to NICE[3]

and the process of assessing them has been taken on by a new group in England, the Patient Access Scheme Liaison Unit, whose role is to examine the ability of NHS organisations to implement PASs. In the UK, PASs have gained widespread acceptance by the pharmaceutical industry, which suggests that risk-sharing plans may become a staple feature of the market in the future.[4]

PASs will only be effective in delivering financial value to the NHS if they can be implemented and managed by the NHS.

The British Oncology Pharmacy Association issued a position statement on risk-sharing schemes in March 2009, summarising the issues around management of financial, governance and administrative risks.[5]

Other than this there is a lack of published research on the impact of these schemes on the NHS and its ability to ensure the benefits of the schemes are maintained. Most recent publications are discussion/opinion pieces on the use of the schemes.[6],[7]

Through this research we sought to look at the impact on pharmacy of implementing patient access schemes to improve access to cancer medicines in the NHS.

Aims

The aims of this research were: to assess the impact of the introduction of PASs for cancer medicines on front-line NHS staff; to identify problems; to gather feedback on how the schemes are working; and to identify what makes a good scheme.

Method

A survey (online questionnaire) was used to gather data on the uptake of schemes, impact on service capacity and suggestions for improving schemes.

The questionnaire asked about PASs for four cancer medicines that were in operation for at least 12 months between 2007 and 2009: erlotinib (Tarceva; pre-NICE appraisal) for lung cancer; sunitinib (Sutent) for renal cell cancer or gastrointestinal stromal tumour; bortezomib (Velcade) for multiple myeloma; and cetuximab (Erbitux) for advanced colorectal cancer.

The questionnaire asked about the running of each scheme. There was a series of general questions to allow comparison of schemes. For each scheme respondents were asked for their assessment of the time taken running the scheme per patient episode. A subjective assessment of the rating of the scheme was also required. This was to assess whether any one type of scheme was more favourable than another.

Limitations

It was not possible to draw statistically significant conclusions about the impact of PASs UK-wide from the data collected — only 37 out of 131 NHS trusts in England responded. This could be due to difficulties in collecting data on medicines use in the NHS or to the wariness of provider trusts to share information that might demonstrate failure to deliver the benefits of PASs to the commissioning primary care trusts.

The results did not capture the views of the nursing teams, medical staff, finance departments and PCTs also involved in managing PASs. Pharmacy departments were targeted because they tend to lead on the introduction of new cancer medicines and hence have become heavily involved in both assessing and implementing PASs.

Results

The estimated sample size was 131 NHS trusts. A return rate of 28% was achieved with responses from 37 trusts. Data were collected for 756 patients treated in PASs. The research showed:

- Refunds for two of the common PASs (sunitinib and bortezomib) may not have been passed on to the funding PCT in 50% of cases

- 73% of respondents reported that they did not have capacity to take on any more schemes

- Funding needs to be found for staff time dedicated to tracking and managing PASs, preventing missed claims and reducing the risk to the NHS

- There is no one preferred scheme; however, simpler schemes with fewer requirements for data collection and monitoring are preferred

- The development of a set of national standard templates for PASs to allow manufacturers to select a familiar “off the shelf” scheme would benefit the NHS

- There is a need for flexibility around any time limits for processing claims; ideally at least 90 days should be allowed to process claims

- In general, schemes linked to measurement of a clinical response took longer to administer and were associated with more problems

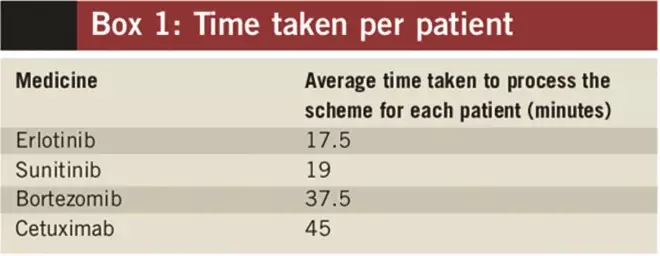

The questionnaire aimed to find out what, if any, capacity is needed to manage PASs, specifically how much extra time is needed for each patient episode (Box 1 shows the time per patient episode). The results for specific schemes are discussed below.

Box 1: Time taken per patient

Discussion

Use of PASs is part of a series of measures designed to improve access to high-cost medicines. In his November 2008 report to the Health Secretary, the national cancer director recommended that the DH should work with the pharmaceutical industry to promote more flexible approaches to the pricing and availability of new drugs.[9]

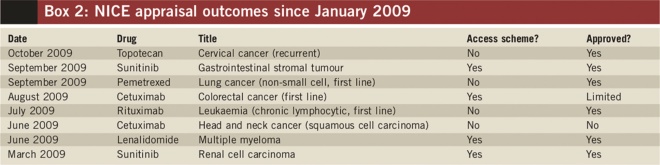

The impact of PASs can already be seen. Box 2 lists cancer medicines approved by NICE since 2009 where use of a PAS has helped make them cost effective. Out of the seven appraisals use of PASs has allowed four to be approved that otherwise would not.

Box 2: NICE appraisal outcomes since January 2009

Bortezomib

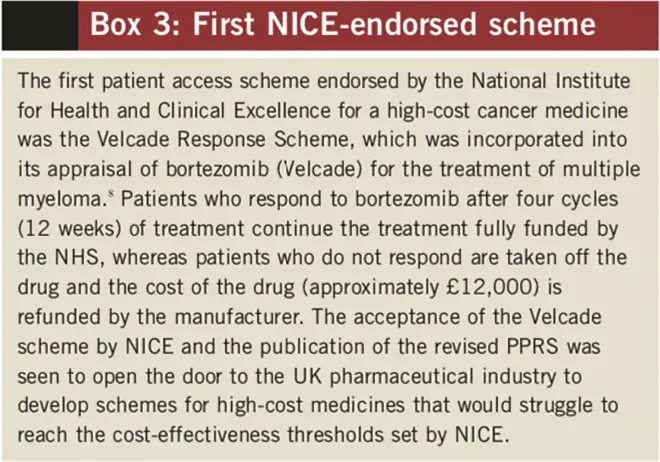

The greatest amount of data was gathered on the bortezomib (Velcade) “VRS” scheme, which had been in operation the longest (see Box 3) and was approved by NICE. The scheme has issues around tracking and ensuring that monies for patients who stop bortezomib after non-response are claimed.

Box 3: First NICE-endorsed scheme[8]

A key feature of the comments was the difficulty experienced by pharmacists managing the scheme when they were not directly involved in the clinical management of the patient. Those that were managing the VRS successfully had allocated a member of staff to track all patients manually and follow up on a monthly basis. This was highly labour intensive. The 60-day claim period was cited as being too tight, with some trusts reporting having missed claims. Janssen-Cilag, the manufacturer of bortezomib, has highlighted that getting the best out of the VRS depends on good patient tracking and prompt submission of claims.[10]

Cetuximab and erlotinib

Of the four schemes studied here, the simplest was perceived to be the erlotinib (Tarceva) “TAP” scheme. It was not necessary to track individual patients since a discount in the form of a credit note was processed automatically by the manufacturer. The problems encountered appeared to be general problems with handling credit notes and maintaining financial flows. This scheme was abandoned when NICE approved erlotinib in November 2008 and was replaced by a discounted price. Insufficient data were gathered on the cetuximab scheme to draw any firm conclusions, but opinion was unanimous that the restricted time period (five days) for processing claims was unworkable. The NHS needs the flexibility to be allowed to make claims retrospectively and tight timescales for claiming rebates will mean such schemes will not work.

Sunitinib

Pfizer’s scheme for sunitinib (Sutent) for renal cell carcinoma and GIST offers the first cycle (month) free and then a 5% discount on list price. The scheme required each patient to be registered with a form sent to the manufacturer to enable free stock to be supplied.

The research showed that pharmacy computer systems are often not set up to handle free stock. This can have a detrimental effect on the average price of a drug and make the charging/recharging of drug costs between trust finance departments and the PCT that pays for the cancer medicines difficult. The success of the sunitinib scheme depends on the prescriber communicating with pharmacy and completing the claim form every time a new patient is started on the scheme.

The results showed that in only 38% of cases was the form completed and sent to pharmacy by the prescriber. Very few respondents were successfully managing to track the discounts and link discounts to particular patients. Asked if the discount was passed on to the PCT that funded the drug, this was only confirmed in 47% of cases.

As an example of the financial risk to the NHS, our review of the costing template for NICE technology appraisal 169 (renal cell carcinoma — sunitinib) estimates that implementation of the scheme could save the NHS in England £7,224,890 a year. This research suggests that for this single scheme only £3,396,398 may be being passed on to PCTs, leaving £3,828,492 a year unaccounted for at best and, at worst, left unclaimed by the NHS.

Capacity for schemes

The research confirms that pharmacy staff play a key role in implementing and managing these schemes. However, it is clear that PASs also have an impact on nursing, medical, administration and finance department time. Some 80% of respondents agreed that risk-sharing schemes should not be accepted unless the capacity to manage them is properly resourced and has been included in the scheme. There is a strong argument for funding staff to run schemes to ensure that no claims are missed and no income is lost. For a scheme such as the bortezomib VRS it can be seen that missing just two claims could cost £24,000. Therefore, investing in staff to track and co-ordinate schemes, thereby avoiding missed claims, could pay for itself. The research has highlighted NHS concerns around the ability of IT systems to process the rebates, free stock or credits. The research showed that no single scheme was preferred. The ability to run a scheme successfully depends on local variables and cannot be predicted easily.

Conclusions

It appears that pharmacy departments are trying to implement and manage PASs at a local level, but are doing so within a complex NHS that does not yet collect data on individual patients routinely. The retrospective nature of rebates also means that PASs can be difficult to manage within current NHS financial arrangements. This, in turn, means that much NHS staff time seems to be spent manually tracking patients, retrospectively adjusting stock control systems and ensuring financial systems account for the true cost of the drug.

The purpose of PASs is to allow drug prices to reflect value to NHS patients more accurately and increase access to cost-effective innovative medicines. This research shows that the NHS may be failing to deliver this worthy purpose and, unless properly managed and supported, that it will bear the financial risk of the schemes.

The risk to the pharmaceutical industry is that the NHS will cease to accept PASs if they are not workable in practice. It is clear that drug pricing and access to high-cost medicines will continue to remain a sensitive area for the NHS and that more research on the matter is needed. It could be argued that our research poses the question: “Do PASs deliver the value for money to the NHS and its patients that they promise?”

About the authors

Steve Williamson is a consultant pharmacist for cancer services, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, and David Thomson is lead pharmacist, Yorkshire Cancer Network.

Email: steve.williamson@northumbria-healthcare.nhs.uk

References

[1] Department of Health. The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme. October 2009. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/DH_091825 (accessed 19 May 2010).

[2] Office of Fair Trading. The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme. A Market Study. 2007. www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/comp_policy/oft885.pdf (accessed 19 May 2010).

[3] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the single technology appraisal process. Section 5: Patient access and flexible pricing schemes. June 2009. www.nice.org.uk/media/F2B/FC/Section5PatientAccessFlexiblePricingSchemes.pdf (accessed 19 May 2010).

[4] Cook JP, Vernon JA, Manning R. Pharmaceutical risk-sharing agreements. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;27:551–6.

[5] British Oncology Pharmacy Association. Cancer Network Pharmacists Forum position statement on “risk sharing” schemes in oncology. March 2008. www.bopawebsite.org (accessed 19 May 2010).

[6] Wynd K. Risk sharing schemes — improving patient access to new drugs. Hospital Pharmacist 2008;15:114.

[7] Williamson S, Thomson D. Do risk share schemes cause more problems than they solve? British Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2009;1:54–5.

[8] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bortezomib monotherapy for relapsed multiple myeloma. October 2007. www.nice.org.uk/ta129 (accessed 21 June 2010).

[9] Department of Health. Improving access to medicines for NHS patients: a report for the Secretary of State for Health by Professor Mike Richards. November 2008. www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 21 June 2010).

[10] Janssen Cilag. VRS satisfaction research questionnaire. VRS Newsletter; January 2009.