VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System

Redesigning the labels of intravenous medicine bags can “significantly” reduce the risk of administering the wrong drugs during an operating theatre emergency, according to research published in the Journal of Patient Safety

[1]

.

Researchers found the chance of selecting the right drug was more than twice as high with bags that had a redesigned label compared with those that had a traditional label.

“Medication safety organizations have published recommendations on the design of optimal medication labels, but there is minimal evidence that their adoption will improve medication safety in real clinical practice settings,” say the researchers, who tested the use of opaque, white, two-sided medication labels on intravenous medicine bags and the use of inverted text for highlighting vital medicine information.

The study involved 96 anaesthesia trainees who took part in a simulated emergency in an operating room or theatre. A surgeon called for an emergency administration of hetastarch (volume expander) for a simulated patient in an unstable condition. The trainees had to select the product from the fluid drawer of the anaesthesia cart.

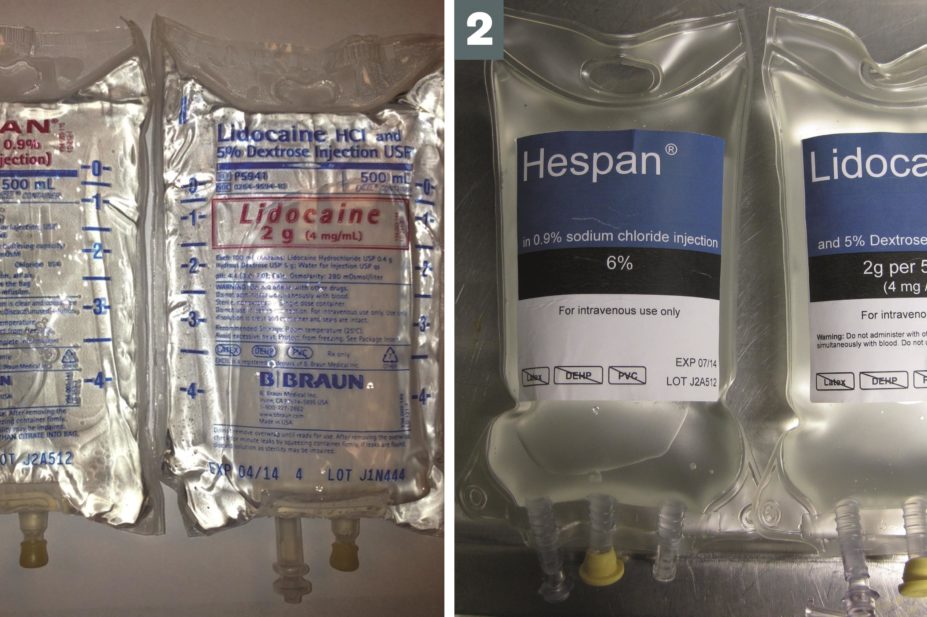

In order to make the issue of clear labelling even more critical, the cart was incorrectly stocked with bags of lidocaine — a local anaesthetic — in the place where hetastarch was normally found.

The cart had three 500ml IV bags of hetastarch and one 500ml IV bag of lidocaine. Products had either the standard labelling with information printed in small text on one side of clear bags, or redesigned labelling that included opaque, white two-sided labels. The text on the redesigned labels was also inverted so there were white letters on a black background.

In the simulation, 63% of the trainees selected the hetastarch bag that had redesigned labels compared with 40% who chose the hetastarch bags with the standard labelling (odds ratio, 2.61, 95% confidence interval 1.1–6.1; P=0.03).

The results showed, according to the researchers, that the “redesigned label prevented some potentially catastrophic errors from reaching the simulated patient”.

Theo Raynor, a professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Leeds, says that labelling in itself is only part of the solution to reduce the risk of medicine errors.

The important safety measures in cases like this are for people to read the information on the label and look at it against what they are being asked to do, he says.

“I think there are so many differences between the traditional and the new labels that it is hard to pick out which had the most impact,” he says. “But I do like the design of these new labels because they are so clear; the colour contrast and the typeface is good and one of the really effective ways of highlighting information is to have it [written] white on black.”