Abstract

Medication errors can occur at any stage of the medication use cycle: prescribing, dispensing, administration or monitoring. Medication errors can have grave consequences, particularly in older and frail patients. These patients are often residents in care homes, which found themselves in the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic for failures in upholding the standards of patient safety.

This systematic review investigates the prevalence and nature of medication errors involving adult patients in UK care homes. A total of 17 studies were selected for review. Overall, medication errors occurred widely, with prescribing and administration errors emerging as the most common. Risk factors included polypharmacy, dementia, dysphagia, understaffing and lack of communication between prescribers, pharmacy and care staff. Problems identified include the frequency of inappropriate use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia and the lack of appropriate knowledge among staff administering medication to patients with dysphagia, highlighting the need for advanced pharmacist intervention.

Keywords: Medication errors; care homes; patient safety

Key points

- Antipsychotic drugs are used inappropriately in care homes to manage behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, increasing the risk of stroke and death among residents with dementia;

- Residents with dysphagia requiring medications in formulations other than oral dosage forms are more likely to have medications omitted or administered inappropriately;

- Nurses and carers in care homes could benefit from patient-centred workshops and training about the appropriate use of medicines, particularly high-risk drugs, and complex dosage forms, such as inhalers. These workshops could be designed and delivered by specialist pharmacists;

- Regular pharmacist-led medication reviews should be implemented in all care homes to reduce inappropriate prescribing, improve patient drug safety and make cost savings;

- More research is required into the impact of medication errors on patients’ health outcomes and quality of life in care homes;

- It is important to encourage and provide appropriate training to support reporting of medication errors on the National Reporting and Learning System website.

Introduction

Medication errors are defined as any preventable errors that occur in any part of the medication use cycle, whether or not they result in patient harm. Medication errors may be classified according to where they occur in the medication use process:

- Prescription (e.g. inappropriate drug, illegible handwriting, route errors);

- Dispensing (e.g. dose, substitution errors);

- Administration (e.g. preparation, delay errors);

- Monitoring (e.g. missed signs, inadequate follow-up)[1].

Medication errors are a major cause of death and debilitation among patients in both primary and secondary care. They are responsible for 12,000 deaths across the NHS every year and cost the NHS up to £1.5bn annually[2]. They are also responsible for 6% of hospital admissions and prolong hospital stays by up to 14 days[3–5]. Patients may never fully recover from the consequences of a medication error and the damage such errors inflict on patient relationships with healthcare professionals and the public confidence in healthcare institutions is also a concern.

The prevalence of medication errors varies across care settings. One study estimated that primary care accounts for 38% of all errors and hospitals account for 20%, but care homes have the highest number of medication errors, at 42%, despite covering fewer patients[3].

‘Care home’ is an umbrella term for care facilities for people who cannot take care of their health and wellbeing independently at home[6]. There are two types of care home: residential homes and nursing homes. Both types of home provide care 24 hours per day; however, nursing homes have qualified nurses on the premises[6]. In 2011, 291,000 people lived in care homes across England and Wales, with 10.4% of residents aged 65–74 years and 59% of residents aged 85 years and over[7]. Approximately two-thirds of care home residents have dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Society[8]. Younger people (18–64 years) with learning disabilities may also occupy care homes. Approximately 22% of people with a learning disability live in care homes[9]. The UK has an ageing population, which is likely to create an increased demand for care homes in the future[7].

Owing to their age and health conditions, care home residents tend to be high-risk patients who are more likely to suffer major harm from a medication error. Residents tend to be older, with functional or cognitive impairment, and taking multiple medications. In addition, residents frequently transfer across other care settings and understaffed care homes. Care home policies can increase the risk of medication errors; for instance, carers can use their discretion to decide whether to administer over-the-counter (OTC) products to residents who might need them[10]. The carer would have to sign that they have the skills to administer the OTC product and be accountable for their actions but there is no requirement for specific training, education or professional registration[10]. There are many drug interactions between OTC and prescription medications that carers may be unaware of, resulting in significantly increased risk of medication error.

Although gaps in the safety culture in UK care homes have been previously reported, most research about medication errors has been conducted in hospitals[11,12]. In addition, most research was conducted in the United States, rather than the UK[11]. The aim of this review is to explore medication errors in UK care homes and outline the interventions that could improve error rates in this sector.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[13].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria:

- Based in the UK;

- Adult population, including older people and disabled people;

- Published between January 2008 and February 2021;

- Primary (peer-reviewed) literature, including cohort studies, case–control studies, interviews and cross-sectional studies;

- Non-peer-reviewed (grey) literature (e.g. government reports, clinical commissioning group reports and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] evidence summaries);

- Full text accessible via Kingston University library service;

- Must involve care homes, either nursing or residential (or both);

- English language;

- Include any type of medication errors.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

- Systematic and narrative reviews;

- Did not separate care home medication errors from other settings, such as hospitals, in their data analysis;

- Discussed adverse drug reactions rather than medication errors;

- Focused on paediatrics;

- Only available in the form of abstracts.

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken by the author HP across multiple databases: Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus, Wiley and Science Direct. The reference lists of some articles were scrutinised for further eligible studies. Some articles were also identified through searching the grey literature (see Supplementary Table).

The research question was split into four main focuses: population, healthcare setting, location, and outcome. For each focus, relevant keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms were identified. These were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to form the search strategy for each database. Filters were applied to restrict the search to articles written in the English language and those published in 2008 onwards (see Supplementary Table).

Study selection

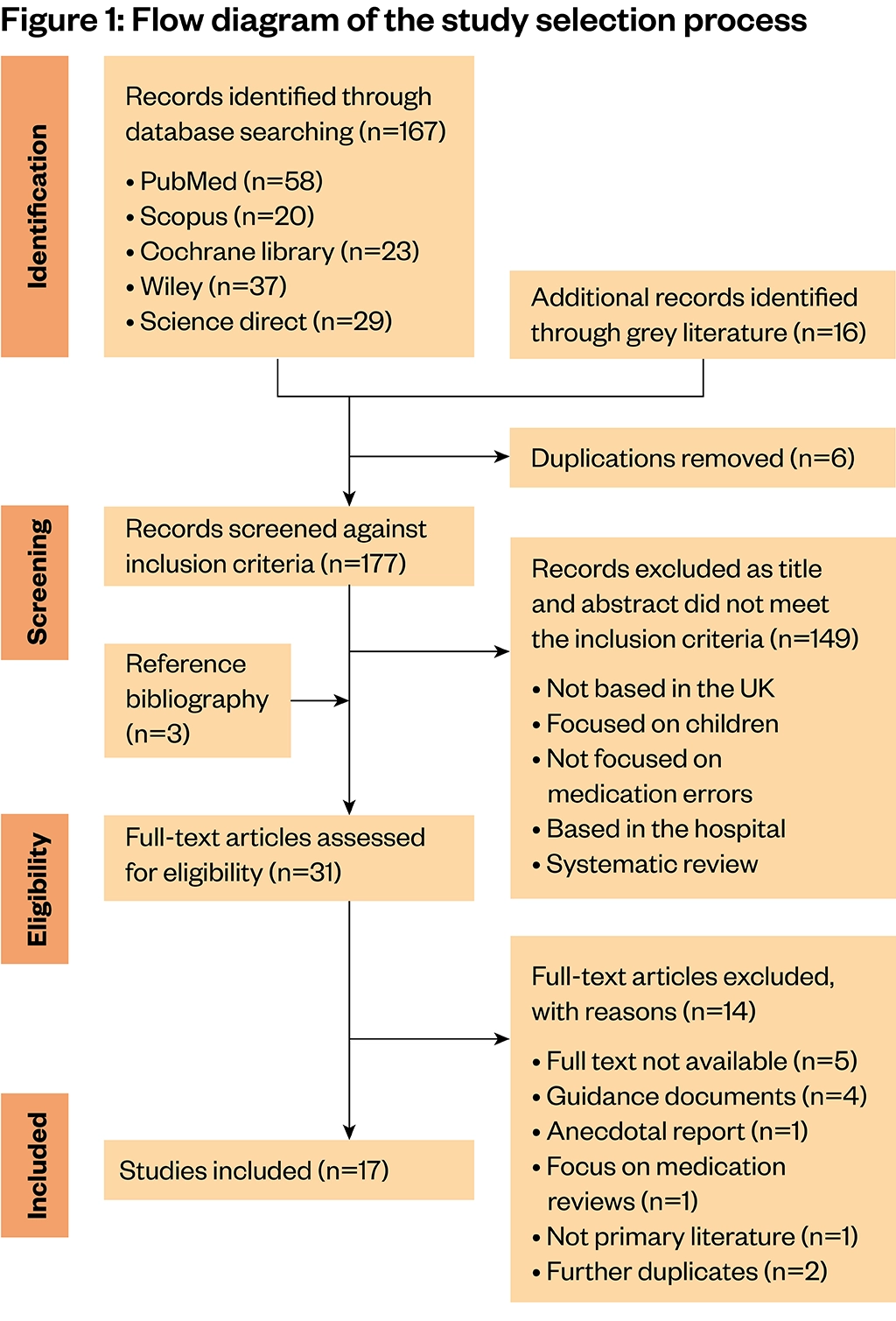

The articles were screened against the inclusion criteria by the authors, HP and MB, according to the PRISMA flow chart (see Figure 1).

Evaluation of studies

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (see Table 1) was used to assess the risk of bias and the methodological quality of studies, including retrospective and prospective cohort studies and cross-sectional studies[14]. Studies scoring more than six points (out of a maximum of nine) were considered good quality while studies with a score of less than six points were deemed low quality.

Data extraction and synthesis

The following information was extracted from the studies and recorded in tables:

- Study characteristics, including study title, author, publication year, primary outcome, study design, patient focus, type of care home, number of residents in the study, number of homes;

- Participant’s characteristics, such as the mean age and percentage of females in the study, polypharmacy, functional impairment and cognitive impairment of the residents;

- Information on prevalence of medication errors, types of medication errors, detection method, harm reported and risk factors.

Results

Overview of selected studies

Searching PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Wiley, Cochrane Library and the grey literature yielded 183 articles; 6 duplicate articles were removed. The remaining 177 articles were screened by title and abstract based on the inclusion criteria. 147 articles were excluded as they did not fit the inclusion criteria. Scrutinising the reference lists of some of the articles retrieved in the search identified three additional potentially relevant studies; of these, one met the inclusion criteria. For the remaining 31 studies, where it was not possible to decide whether to include or exclude an article based on its title and abstract, full text was accessed and scrutinised, and 14 studies were deemed not to meet the inclusion criteria for the following reasons: full text not available (n=5), guidance documents (n=4), anecdotal report (n=1), focus primarily on medication reviews (n=1), not primary literature (n=1) and further duplicates (n=2). A total of 17 studies were included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the studies

The characteristics of the selected studies are summarised in Table 2. There were six retrospective cohort studies[15–20], five prospective cohort studies[21–25], three cross-sectional studies[26–28] and three interviews[29–31]. Five studies focused on the use of psychotropic drugs in patients with dementia[16,21,27–29], and three studies focused on medication errors involving patients with diabetes[18–20]. Four studies examined the link between using different medication systems and formulations in care home residents with dysphagia and the occurrence of medication errors[22–25]. Four studies investigated ways to improve medication safety[20,21,30,31].

The majority of the studies included both nursing and residential homes. Two studies were conducted in nursing homes only[19,24]. One study included patients from residential homes only[16]. In 10 studies, patients had a mean age of >80 years[15–17,19,22,23,25–28]. In eight studies, the majority of the residents in the care homes were female (range 69–80%)[15–17,22,25–28]. Four studies reported functional impairment of the residents (e.g. dysphagia)[22–25]. Four studies reported that residents had some cognitive impairment (dementia)[16,21,27–29]. Nine studies reported that polypharmacy was prevalent in care homes[15–17,19,20,22,23,25,27].

Quality assessment of included studies

All observational studies assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale scored at least six points, meaning they were of good quality. The median score was seven, indicating a low risk of methodological bias overall. Most studies lost points because of the dropout rate of participants or the comparability of the non-exposed and exposed cohort. The study by Maidment et al. had a particularly high dropout rate, as some residents withdrew and some died[21].

All studies had clearly presented aims and objectives and some discussed their own limitations[17,20,21,23]. Two studies described similar limitations — there was not enough information on the indications of some medications and the resident’s clinical conditions[17,25]. Therefore, the prevalence of inappropriate prescribing should be viewed with caution. One study mentioned that there was not enough care staff and homes in the study to assess the true effectiveness of the patient-centred workshops[21]. Another study stated that the confidence intervals for the prevalence of medication errors were large[25].

Prevalence and types of medication errors

Medication errors occurred widely in care homes (see Table 3). The prevalence of medication errors was reported in different ways:

- Proportion of residents suffering at least one potentially inappropriate prescription[15,16,20,28];

- Error rate by opportunity for error[22,25];

- Mean number of errors per resident[23];

- Error rate per resident or per administration[24].

In addition, some studies reported a large proportion of residents being prescribed high-risk medicines, such as psychotropic drugs, which would suggest inappropriate prescribing[17,26,28]. The heterogeneity in describing the prevalence of medication errors presents a challenge for comparing these studies and their outcomes. With regards to the type of error, most studies focused on inappropriate prescribing[15–17,21,22,24,26–29] and five studies discussed administration errors[18,22–25]; only three studies addressed monitoring errors[18,22,30].

There were two main detection methods used in the studies: retrospectively and in real time. The retrospective method looked at past prescriptions and medication administration records[15–20,26–28], and the real-time method observed errors during medication rounds[21–25].

Risk factors and consequences of medication errors

Various risk factors for medication errors in care homes were identified (see Table 3). Several studies reported a correlation between polypharmacy and the rate of medication error[15,16,19,20]. There may be a link between age and gender and medication errors; however, the relationship is not consistent across studies. For instance, Barnett et al. reported that patients were more likely to be prescribed a potentially inappropriate medication if they were younger and female[15]. On the other hand, McCowan et al. reported that the older the patient, the more likely they were to be prescribed an antipsychotic or hypnotic drug, and Johnson et al. found that male residents were more likely to be prescribed benzodiazepines[17,26].

Patients with functional or cognitive impairment were subject to more medication errors. For instance, patients with dysphagia were more likely to have medications omitted, and patients with dementia were less likely to receive pro re nata (PRN) medications appropriately[24,27]. Organisational factors were widely reported across studies. Most significantly, there was lack of effective communication between all professionals involved in the care of patients, including GPs, the hospital team, pharmacy and care home staff[22,24,25,31].

There was limited information on the potential harm of medication errors. Only one study used a validated tool to assess the potential harm of medication errors[22]. The average harm score for all types of errors was relatively low, suggesting that most medication errors were associated with no or low harm[22].

Classes of medications affected by medication errors

The most common drugs targeted in investigating medication errors were:

- Psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants);

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

- Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs);

- Statins;

- Insulin;

- Glucose-lowering drugs.

Interventions to reduce medication errors

Across the studies, interventions to reduce medication errors included medication reviews, patient-centred workshops and a pharmacy-led barcode system. Two studies reported that pharmacists conducting medication reviews made recommendations to stop or review potentially inappropriate medications, which were partially implemented by GPs[20,21]. Patient-centred workshops targeting staff involved in the care of dementia patients were well received and staff reported that they were more likely to apply a holistic approach to patient care and rely less on medications[21]. One study focused on developing a ‘medication-monitoring’ error definition to help identify monitoring errors in the care home[30]. The effect of this intervention was not assessed.

The introduction of a pharmacy-led barcode system to allow direct transfer of medication data between the pharmacy and care home saw a reduction in the number of interruptions to staff during medication rounds, from 100% to 70% for care staff and 86% to 42% for nurses. Also, the awareness of ‘near misses’ increased from 40% to 74% for carers and from 0% to 83% for nurses[31]. Table 4 has details on the interventions assessed in the studies and their effect on reducing medication errors.

Discussion

Medication errors in care homes were common in all the studies assessed. This information is not surprising, because the patients who reside in care homes are usually older people with known patient safety risks, including comorbidities, polypharmacy, dementia, lack of physical dexterity and dysphagia. The most commonly found types of medication errors were prescribing and administration errors.

Several studies highlighted that high-risk medications, including psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants), were prescribed at a high rate in patients in care homes[15–17,21,26–28]. In particular, antipsychotics continue to be widely used to treat the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Antipsychotics increase the risk of stroke and death in patients with dementia, and could result in an additional 1,800 deaths and 1,620 cerebrovascular adverse events each year in the UK[32]. NICE therefore recommends that antipsychotics should be used with caution in this population[33]. However, care home staff can lack detailed knowledge of the side effects of antipsychotics and tend to associate antipsychotic use with positive outcomes for both the patient and the staff caring for the resident[29].

GPs and consultants sometimes prescribe antipsychotics for patients who have problematic symptoms and may be under the impression that the benefits of maintaining balance in the care home outweigh the risks of adverse effects[29]. Several studies found that when a resident became agitated and aggressive, carers often resorted to giving PRN antipsychotics to manage the situation, especially during medication administration rounds[21,29]. However, non-pharmacological methods, such as calming music and understanding that residents demonstrate aggression when an unmet need is not addressed, are considered first resort[33]. Effort should therefore be directed to holding patient-centred workshops to train care staff on using non-pharmacological interventions when a resident demonstrates the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Regular medication reviews by prescribers or pharmacists that target, but are not limited to, these medicines are required to tackle the inappropriate prescribing of psychotropic drugs in care homes. Tools such as the Beers criteria and STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions) criteria can be used to support medication reviews[15,16,34,35]. Care homes would also benefit from recruiting specialist dementia care pharmacists.

PRN medications for the short-term management of other symptoms, such as pain, are also prone to medication errors[24,27]. Residents with cognitive impairment often rely on the carer’s judgement on whether they require PRN medication. It was noted that these residents, often lacking the ability to communicate, were less likely to receive PRN medications for pain or constipation[27,36]. Staff sometimes lack the knowledge and skills to perform pain assessments or identify complaints such as constipation. PRN medicines, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, are often continued without a clinical indication, which risks masking the symptoms of other conditions, potentially harmful drug interactions or adverse drug reactions (e.g. acute kidney injury)[27]. Care home staff should receive more education and training on the use of PRN medicines, and pharmacists conducting medication reviews need to ensure that PRN medicines are not ignored.

Polypharmacy was identified as a risk factor for medication errors in several studies. Medicines were often continued without a valid indication (e.g. statins, PPIs)[16,19]. Statins are used to prevent cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; however, owing to the residents’ age and life expectancy, statin use in this population may be inappropriate[19]. Statins can increase the risk of muscle toxicity in older people owing to poor renal function and statins are likely to interact with other medications the patient may be on. Long-term use of PPIs has also been linked to increased risk of hip fractures, hypomagnesemia, kidney disease, pneumonia and Clostridium difficile infections[37]. GPs are responsible for most prescribing for care home residents, and it is important that they are well supported to deliver appropriate prescribing and de-prescribing with extra training, and should work closely with pharmacist prescribers and other stakeholders, including care home staff, patients and their relatives. Tools to assist in the identification of patients at high risk of harmful polypharmacy and regular medication reviews would reduce the risk of adverse drug reactions. Deprescribing guidelines on how and when to discontinue a medication would also support clinicians in decision making.

Several studies found that non-oral drug formulations have a higher risk of being administered incorrectly. Inhalers had the highest rates of administration error, as they are complex devices[22,23]. Staff can find it difficult to administer inhalers correctly — the inhaler is often not shaken properly and the resident does not always hold their breath[22]. The metered dose inhaler with a spacer is the preferred type of inhaler for the older population[36]. Spacers remove the need to coordinate pushing the button and inhaling at the same time. It can also be administered to a resident by a carer or a nurse.

Liquid formulations are commonly prescribed in care homes, as older patients are more likely to develop some form of dysphagia (when an individual struggles to swallow food or medication, especially solid oral dosage forms). It can result in aspiration predisposing to pneumonia, which is one of the leading causes of death in patients with stroke, Parkinson’s disease and dementia[38–40]. Residents with dysphagia were more likely to experience an administration error compared to those without dysphagia[24]. The main cause for this was inappropriate prescribing of formulations[24]. Residents with dysphagia were more likely to have medicines omitted, as staff were hesitant to tamper with the medication for ease of administration[24]. The primary reason for a patient receiving an inappropriate formulation was failure by the carer to highlight the need for an alternative[22].

Special-order liquid formulations, such as bisoprolol, simvastatin and gliclazide liquids, tend to be much more expensive than tablets[19]. Liquids have a considerable risk of administration error caused by inaccurate volume measurement and suspension bottles not being shaken properly, leaving a residue at the bottom[22–24]. It might be possible to substitute these expensive liquid preparations with tablets that can be crushed, to reduce cost; however, guidance in the form of a list of medicines that can be safely crushed should be made available to care staff, to prevent them altering medicines that have potential for increased toxicity, decreased efficacy, palatability and stability concerns. Communication between care staff, prescribers and pharmacists is vital in identifying patients with swallowing difficulties and ensuring an appropriate and cost-effective formulation is prescribed, obtained and correctly administered.

Tablets and capsules can either be packaged into monitored dosage systems (MDS) or dispensed in original packaging. MDS can simplify workloads and save time for staff when administering medicines in care homes. Items dispensed in original packaging were more likely to be involved in administration errors than ones dispensed in MDS[23–25]. However, dispensing errors were more likely to affect MDS medicines[22]. Not all medications can be packaged into MDS — for instance, effervescent tablets and other moisture-susceptible tablets[22–25]. For this reason, patients may have both MDS and original-packaging systems used in parallel[25]. Moreover, repackaging of medicines into MDS is associated with longer dispensing times and significantly higher costs[22]. More research is therefore needed to confirm whether MDS can truly offer a safety advantage in care homes.

Medication monitoring is an integral part of the safe and effective use of medicines. Most monitoring errors resulted from a failure to request monitoring for drugs, such as diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors[22]. Other barriers included residents disliking blood tests, staff shortages and a lack of knowledge among care staff about what drugs require monitoring or when to request it[22]. Standage et al. have proposed a definition of ‘medication monitoring error’ that would make it easier for GPs and pharmacists to identify such errors[30]. Medicine-specific criteria were developed and validated for a list of high-risk medicines that need to be monitored on initiation and during maintenance use[30]. Similar interventions should be adopted in all care homes to improve medication monitoring practices. Care staff could be trained to request that certain medicines be monitored. However, with their already high workload, it may be challenging to implement in practice and it is questionable whether this is an appropriate responsibility to place on them. Pharmacist prescribers have the skills to play a leading role in ensuring appropriate monitoring of medicines in care homes.

Organisational factors (also called latent failures) significantly contributed to medication errors in care homes[41]. Several studies found that care staff were often interrupted and distracted while administering medications, sometimes resulting in staff administering a double dose or omitting a medication; in addition, medication administration rounds were often delayed and care homes suffered from staff shortages[22,24,25,31]. Carers also seemed to lack appropriate knowledge about medications, including monitoring requirements, and did not always have effective communication with GPs[22].

Wild et al. designed a barcode system intervention that minimised the distraction and interruption of staff during medication rounds[31]. The presence of the barcode machine made people aware that the carer or nurse was in the process of a medication round and they were discouraged from interrupting[31].

Providing additional education for carers and nurses about medicines, especially high-risk drugs, such as antipsychotics, has the potential to improve their safe use in care home residents[21]. Involving a pharmacist in medication reviews was shown to reduce inappropriate prescribing[20,21]. However, it was reported that often their recommendations were not implemented quickly enough, or not implemented at all, by prescribing GPs[20,21]. There is a need to foster working relationships between pharmacists who serve care homes and professionals working in primary, secondary and social care.

Limitations

This review has some limitations. First, the review has included only studies published in the period January 2008 to February 2021, meaning that some important studies that were published outside this period might have been excluded. The literature search was conducted by only one author (HP), although a systematic approach to database search was used to identify studies. Articles were screened by two reviewers, working independently, ensuring more sound selection of studies according to inclusion criteria. A main caveat, however, was that only full-text studies accessible via a Kingston University subscription were included, which might have resulted in some important findings not being discussed in this review. While this review is not scoping in its nature, it does highlight some important issues that need addressing with regards to medication prescribing and administration in care homes.

There was a heterogeneity in the detection methods used in the different studies to identify medication errors. In some studies, errors were determined retrospectively, looking at past prescriptions, whereas other studies relied on real-time observation during medication rounds. Some studies employed multiple adjudicators to identify medication errors, while others relied only on the judgement of one healthcare professional or researcher. The numbers of errors reported in the review should therefore be viewed as a guide and not as an accurate count of the prevalence of medication errors in care homes.

Conclusion

Medication errors are common in care homes. The most frequently discovered and investigated types of medication errors in the literature were related to administration and inappropriate prescribing. Care staff are in need of support and training to be able to use medicines safely to care for vulnerable patients with multiple physical and cognitive needs. Interventions, including pharmacist-led medication reviews, patient-centred workshops and barcode systems, have been demonstrated to be effective tools in reducing medication errors. More funding and support should be provided for conducting further research into medicines optimisation in care homes.

Nominate an early-careers researcher today for the OPERA23 award

Help us in our search for outstanding early-career researchers who are accomplishing great things in pharmacy and pharmaceutical science.

For entry criteria and details on how to nominate a colleague, click here.

- 1Slight SP, Tolley CL, Bates DW, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in a UK hospital during the optimisation of electronic prescriptions: a prospective observational study. The Lancet Digital Health. 2019;1:e403–12. doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30158-x

- 2The Report of the Short Life Working Group on Reducing Medication-Related Harm. Department of Health and Social Care. 2018.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/683430/short-life-working-group-report-on-medication-errors.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 3Elliott RA, Camacho E, Jankovic D, et al. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;30:96–105. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010206

- 4Einarson TR. Drug-Related Hospital Admissions. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:832–40. doi:10.1177/106002809302700702

- 5Krähenbühl-Melcher A, Schlienger R, Lampert M, et al. Drug-related problems in hospitals: a review of the recent literature. Drug Saf 2007;30:379–407. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730050-00003

- 6Berg V. What is a nursing home? Carehome.co.uk. 2021.https://www.carehome.co.uk/advice/what-is-a-nursing-home#:~:text=The%20purpose%20of%20a%20nursing,and%20need%20the%20added%20support (accessed Oct 2022).

- 7Living longer: how our population is changing and why it matters. Office for National Statistics. 2018.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 8Home from home. Alzheimer’s Society. 2007.https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/home_from_home_full_report.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 9Housing for people with a learning disability. Mencap. 2012.https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-08/2012.108-Housing-report_V7.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 10Managing medicines in care homes. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 11Gartshore E, Waring J, Timmons S. Patient safety culture in care homes for older people: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2713-2

- 12Oliver D. David Oliver: Let’s be open and honest about covid-19 deaths in care homes. BMJ. 2020;:m2334. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2334

- 13PRISMA 2020 checklist. PRISMA. 2020.https://www.prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA_2020_checklist.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 14Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. The Ottawa Hospital. 2012.https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed Oct 2022).

- 15Barnett K, McCowan C, Evans JMM, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of use of potentially inappropriate medicines in older people: cohort study stratified by residence in nursing home or in the community. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20:275–81. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2009.039818

- 16Parsons C, Johnston S, Mathie E, et al. Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Older People with Dementia in Care Homes. Drugs & Aging. 2012;29:143–55. doi:10.2165/11598560-000000000-00000

- 17McCowan C, Magin P, Clark SA, et al. An observational study of psychotropic drug use and initiation in older patients resident in their own home or in care. Age and Ageing. 2012;42:51–6. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs117

- 18Milligan FJ, Krentz AJ, Sinclair AJ. Diabetes medication patient safety incident reports to the National Reporting and Learning Service: the care home setting. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;28:1537–40. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03421.x

- 19Gadsby R, Galloway M, Barker P, et al. Prescribed medicines for elderly frail people with diabetes resident in nursing homes-issues of polypharmacy and medication costs. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;29:136–9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03494.x

- 20Andreassen LM, Kjome RLS, Sølvik UØ, et al. The potential for deprescribing in care home residents with Type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:977–84. doi:10.1007/s11096-016-0323-4

- 21Maidment ID, Damery S, Campbell N, et al. Medication review plus person-centred care: a feasibility study of a pharmacy-health psychology dual intervention to improve care for people living with dementia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1907-4

- 22Barber ND, Alldred DP, Raynor DK, et al. Care homes’ use of medicines study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18:341–6. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.034231

- 23Alldred DP, Standage C, Fletcher O, et al. The influence of formulation and medicine delivery system on medication administration errors in care homes for older people. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20:397–401. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046318

- 24Serrano Santos JM, Poland F, Wright D, et al. Medicines administration for residents with dysphagia in care homes: A small scale observational study to improve practice. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2016;512:416–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.036

- 25Gilmartin-Thomas JF-M, Smith F, Wolfe R, et al. A comparison of medication administration errors from original medication packaging and multi-compartment compliance aids in care homes: A prospective observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2017;72:15–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.008

- 26Johnson CF, Frei C, Downes N, et al. Benzodiazepine and z-hypnotic prescribing for older people in primary care: a cross-sectional population-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e410–5. doi:10.3399/bjgp16x685213

- 27Griffiths AW, Surr CA, Alldred DP, et al. Pro re nata prescribing and administration for neuropsychiatric symptoms and pain in long-term care residents with dementia and memory problems: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41:1314–22. doi:10.1007/s11096-019-00883-7

- 28Grill P, Marwick C, De Souza N, et al. The burden of psychotropic and anticholinergic medicines use in care homes: population-based analysis in 147 care homes. Age and Ageing. 2020;50:183–9. doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa122

- 29Almutairi S, Masters K, Donyai P. The health professional experience of using antipsychotic medication for dementia in care homes: A study using grounded theory and focussing on inappropriate prescribing. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25:307–18. doi:10.1111/jpm.12464

- 30Alldred DP, Standage C, Zermansky AG, et al. Development and validation of criteria to identify medication-monitoring errors in care home residents. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2008;16:317–23. doi:10.1211/ijpp.16.5.0007

- 31Wild D, Szczepura A, Nelson S. New barcode checks help reduce drug round errors in care homes. Nursing Management. 2011;18:26–30. doi:10.7748/nm2011.09.18.5.26.c8671

- 32Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: Time for action. Department of Health. 2016.https://dementiapartnerships.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/time-for-action.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 33Antipsychotic medicines for treating agitation, aggression and distress in people living with dementia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/antipsychotic-medicines-for-treating-agitation-aggression-and-distress-in-people-living-with-dementia-patient-decision-aid-pdf-4852697005 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 34American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:674–94. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767

- 35O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age and Ageing. 2014;44:213–8. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu145

- 36Nygaard HA, Jarland M. Are nursing home patients with dementia diagnosis at increased risk for inadequate pain treatment? Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry. 2005;20:730–7. doi:10.1002/gps.1350

- 37Jaynes M, Kumar AB. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 2018;10:204209861880992. doi:10.1177/2042098618809927

- 38Zhang S, He W-B, Chen N-H. Causes of Death Among Persons Who Survive an Acute Ischemic Stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14. doi:10.1007/s11910-014-0467-3

- 39Lethbridge L, Johnston GM, Turnbull G. Co-morbidities of persons dying of Parkinson’s disease. Progress in Palliative Care. 2013;21:140–5. doi:10.1179/1743291x12y.0000000037

- 40Foley NC, Affoo RH, Martin RE. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Examining Pneumonia-Associated Mortality in Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;39:52–67. doi:10.1159/000367783

- 41Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768