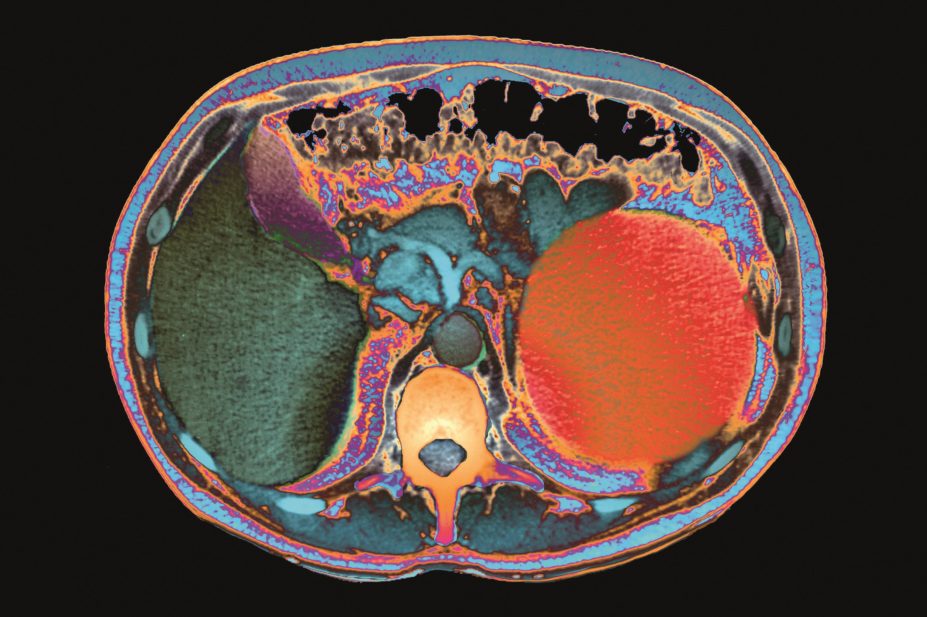

Zephyr / Science Photo Library

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) — used to inhibit gastric acid secretion — are associated with a 20–50% increase in the risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to new research. The study published in JAMA Internal Medicine

[1]

(online, 11 January 2016) also found that H2-receptor antagonists, which are prescribed for the same indications as PPIs, were not independently associated with CKD.

The researchers investigated more than 10,000 participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a prospective epidemiologic study conducted in the United States. Participants had an estimated glomerular filtration rate of at least 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, and were followed for around 14 years. Self-reported PPI use was compared with incident CKD, with adjustments made for various confounders.

The findings were replicated in a second cohort of more than 248,000 patients whose data were collected for the Geisinger Health System, an organisation serving around 3 million residents, primarily in Pennsylvania.

“Our study is observational, and so it does not provide proof that PPI use causes kidney disease,” says corresponding author Morgan Grams, a nephrologist at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “However, there appears to be mounting observational evidence that PPIs — historically, a class of medication thought to be extremely safe — have some adverse effects, including pneumonia, fracture, [Clostridium] difficile infections, acute kidney injury, and low levels of magnesium.”

Siu Man Tin, senior gastroenterology pharmacist and teacher practitioner at Royal Liverpool University Hospital, says the results are interesting and “may mean we should have further concerns on the long-term side effect profile of PPIs”.

“Clinicians should be mindful that PPIs should have a review date and be discontinued or stepped down to the lowest dose to control symptoms,” adds Tin.

Grams points out that given the widespread use of PPI medications, even relatively rare adverse effects can impact large numbers of people. “[Clinicians should] discuss risks and benefits at PPI initiation, readdress the indication for PPI at each clinic visit with the goal of discontinuing use at the earliest possible time, and continue to monitor laboratory parameters such as kidney function and serum magnesium during PPI use.”

Grams adds that caution should be taken when self prescribing PPIs. “I would recommend discussing over-the-counter use with a doctor prior to purchase,” she says.

Ben Lazarus, who led the research, says he would promote judicious use of PPIs as opposed to avoiding them altogether. “There are other options for reducing gastric acid production, such as the older H2-antagonists,” he says. “In our study, and some of the other studies that have looked at possible adverse effects of PPIs, it was found that H2-antagonists weren’t associated with the adverse outcomes under investigation.”

References

[1] Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193