Wikimedia Commons

Use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) increases the risk of long-term kidney damage, a study shows.

Patients who took PPIs were significantly more likely to develop chronic kidney disease (CKD), kidney disease progression, and end stage renal disease (ESRD) compared with those treated with histamine H2-receptor antagonists.

“The constellation of findings suggest a strong and intimate link between PPI use and untoward kidney outcomes,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, a corresponding author from Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri.

The researchers used information from US Department of Veterans Affairs databases to create a cohort study involving 20,270 new users of PPIs and 173,321 new users of H2 blockers. All the patients had normal kidney function at baseline (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >60ml/min/1.73m2).

Over five years, those in the PPI group were 28% more likely to develop CKD and 96% more likely to develop ESRD than patients in the H2-blocker group, the researchers report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

[1]

(online, 14 April 2016).

The researchers also used laboratory parameters to look at the risk of CKD progression; they found that patients in the PPI group were 53% more likely to experience a doubling of serum creatinine and 32% more likely to have an eGFR decline of more than 30% compared with patients in the H2-blocker group.

The risk of kidney outcomes tended to increase according to the duration of treatment. For example, patients treated for 91-180 days were twice as likely to develop CKD than those treated for less than 30 days.

Overall, the rate of CKD was 2,570 and 3,683 per 100,000 person-years in H2-blocker and PPI-exposed groups, respectively; the rate of ESRD was 26.5 and 41.3 per 100,000 person-years.

“We think the public at large and the medical community should be aware of these findings,” says Al-Aly. “PPIs are very widely used, are marketed as safe, and available (without prescription) over the counter.”

Al-Aly says that PPI use should therefore be limited to when it is medically necessary and the duration of treatment restricted to the minimum length of time. But he adds: “Our findings should not discourage the use of PPIs when medically indicated.”

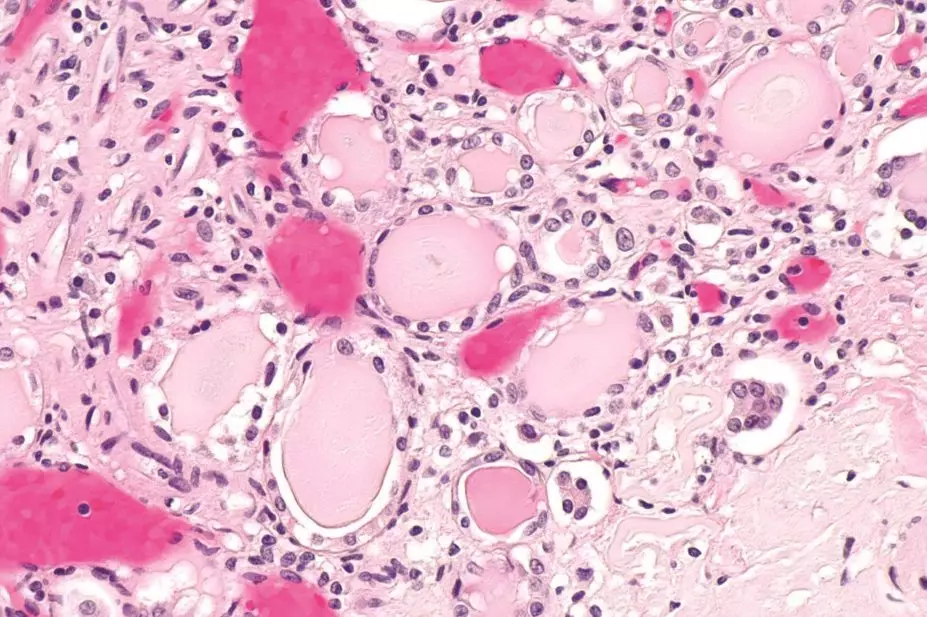

There is a well-established link between the use of PPIs and acute kidney damage, particularly the development of interstitial nephritis, and recent evidence has linked the drugs with CKD. PPIs, used to treat reflux and stomach ulcers, are some of the most commonly prescribed medications in the UK. In January 2015, esomeprazole became the first PPI to be available over-the-counter outside of the pharmacy.

Frank Muller, a regional British Society of Gastroenterology lead, says he and his colleagues at the Kent and Canterbury Hospital previously believed that PPIs were probably the most common drug-related cause of interstitial nephritis.

He says the link between PPI use and renal function needs to be more widely understood, but that it is not completely clear how to manage patients for renal complications while receiving PPIs.

“There is no evidence as yet to confirm that monitoring patients renal function regularly would reduce the risk,” says Muller. “If patients are unwell for whatever reason whilst taking these drugs, it would be reasonable to perform a U&E [urea and electrolytes] measurement.”

Renal function usually improves when the drugs are stopped, he says, and although patients are sometimes given steroids, it is not clear if these enhance renal recovery.

Muller notes that a study is under way to determine if there are genetic markers that predict which patients treated with PPIs are most susceptible to kidney damage.

References

[1] Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121377