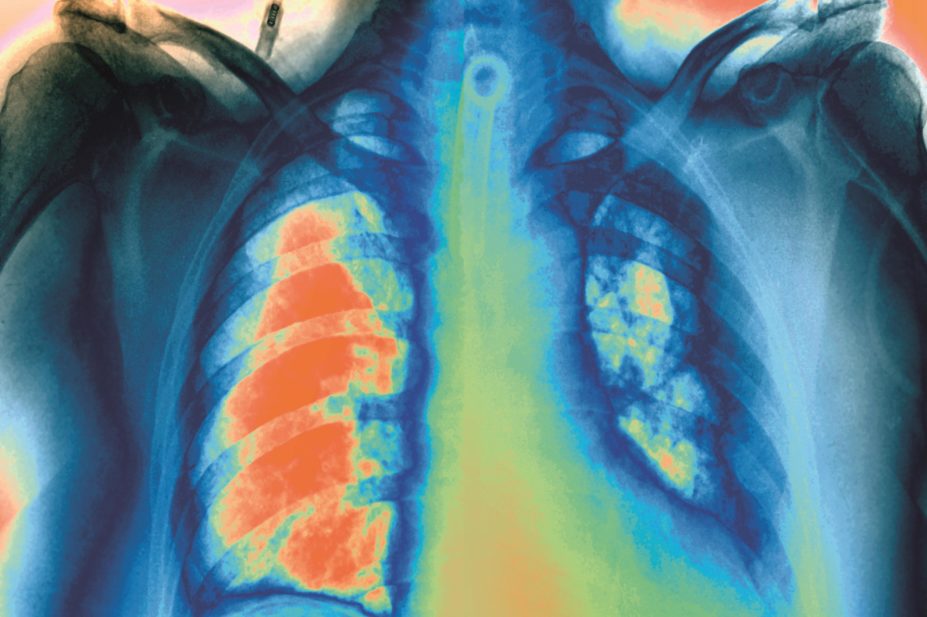

Zephyr / Science Photo Library

The results of a study into the benefits of warfarin for patients who have suffered a blockage in a lung artery suggest that the anticoagulant should be administered indefinitely.

A trial of 371 patients who had experienced a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism (people who had no major risk factor for thrombosis) and who had been treated initially for six months with a vitamin K antagonist were randomised to receive treatment with either warfarin or placebo for 18 months. The warfarin group lost the benefit of that treatment once the drug was stopped, researchers reported in JAMA

[1]

on 7 July 2015.

As expected, the additional 18 months of warfarin therapy was associated with a major reduction of recurrent venous thromboembolism and a moderate increased risk of bleeding over that time. The unknown factor was whether the benefit would be lost in the post-treatment period.

Francis Couturaud of the Universite de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, who led the study, says: “What surprised us the most is the observation that 80% of the recurrent venous thromboembolism were pulmonary embolism that was not provoked and therefore not preventable; 8% of these recurrences were fatal.”

Patients were followed up between 2007 and 2014 in 14 centres in France.

When anticoagulant therapy is stopped after three to six months of treatment, patients with a first episode of unprovoked venous thromboembolism have a much higher risk of recurrence than those with venous thromboembolism provoked by a transient risk factor (eg, surgery). In this high-risk population, extending warfarin beyond three to six months is known to be associated with a reduction in the risk of recurrence if treatment is continued.

Couturaud says the fact that risk was no longer reduced when anticoagulant therapy ended was to be expected. It had been observed that longer anticoagulation therapy has no long-term effect on the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. However, nobody had reported looking at a treatment period as long as two years.

“Even after two years of anticoagulation, the risk of recurrence remains high after stopping,” says Couturaud, calling for indefinite anticoagulation for a high proportion of patients with unprovoked pulmonary embolism.

Couturaud acknowledges the significant increased bleeding risk associated with anticoagulation and suggests that patients should not be treated indefinitely if their bleeding risk is high or if they have some clinical characteristics associated with a lower risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. In these circumstances they should be treated for three to six months.

Helen Williams, consultant pharmacist for cardiovascular disease for a number of NHS organisations across South London, says the study only represents a piece of the puzzle. Although the researchers reported only a minimal increase in risk of bleeding on extended warfarin therapy, the patient numbers were small (fewer than 400), which may have meant that small increases, which were not significant in the study, might be significant in the population as a whole. Nevertheless, she says, the data provide “enough evidence to start thinking about whether we extend the treatment period”.

Although this study was based on a well-established anticoagulant, warfarin, drug manufacturers might be pleased at the prospect of patients going on to anticoagulation therapy for the rest of their lives. “We have to think about the cost of such a strategy,” says Williams.

In the UK, NICE guidelines (CG144) already recommend offering long-term anticoagulation to patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism.