Nicola Rudall

How did you end up working in Namibia?

I was granted a career break for a year from my role as a senior lead clinical pharmacist within the NHS with the intention of working for Médecins sans Frontières. Having gone through its selection process and been put on its register, the only available job was in Afghanistan, which I believed was not for me. I started asking around elsewhere and, through an indirect route via some former colleagues, I heard about the new school of pharmacy in Namibia. It was serendipitous timing because the new school had just received a grant from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which it wanted to use to teach the undergraduate students about clinical pharmacy. I happened to be in the right place at the right time with the skills they were looking for.

What was your role in Namibia?

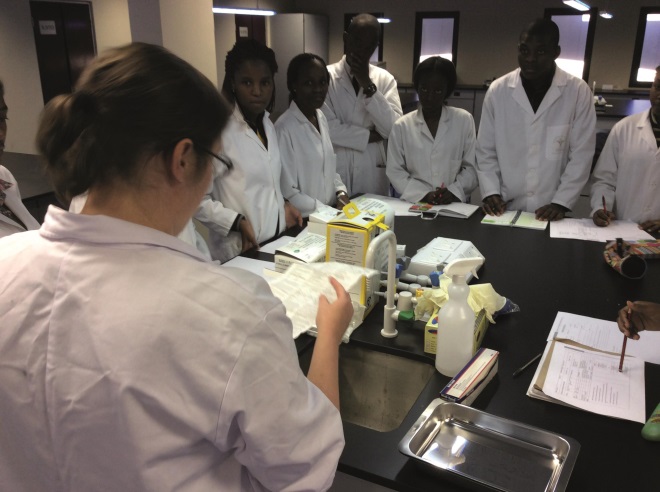

The students in the first pharmacy undergraduate cohort at the University of Namibia (UNAM) were starting their fourth and final year in January 2014, when I started. My remit was to build on the students’ previous hospital pharmacy experience, which they had gained from a four-week placement at the end of their third year, and introduce them to the concept of clinical pharmacy while developing their clinical review skills.

Clinical pharmacy is not really practised in Namibia yet and, with huge health burdens of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis, pharmacists have an opportunity to make a significant, positive impact on patient care. I developed clinical rotations through intensive care (which I specialise in), acute psychiatry, oncology and the tuberculosis wards. The rotations teach the students how to take a clinical approach to pharmaceutical provision, identify issues and interventions and develop patient care plans. The students had four weeks of clinical teaching in each of the two semesters.

Interprofessional working was encouraged, particularly on the tuberculosis wards where they learnt alongside medical and nursing students. I taught various year groups on subjects including clinical skills, pharmacy practice, pharmacotherapy and clinical pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring. I also wrote a proposal for a postgraduate clinical pharmacy masters course, the first of its kind in Namibia.

Source: Nicola Rudall

Nicola Rudall teaching third year students in Namibia

What did you enjoy most about your time in Namibia?

The school of pharmacy is committed to producing high quality, well-rounded pharmacy students and the clinical training was an important part of this aim. Clinical pharmacy was a new concept to the students, but they worked hard and showed a real aptitude for the speciality. I am proud of how much the students learnt and, more importantly, how they applied their new knowledge. Now they have graduated, all class members are employed and completing their internship (equivalent to our pre-registration year). Several of them are keen to become clinical pharmacists in the future. With the postgraduate pharmacy masters programme currently going through the approval process, a path is being created for their future development.

What were the challenges and how did you overcome them?

We took the students into the public sector hospitals which, at that time, had approximately 25 pharmacists working in them nationwide, serving a population of 2.3 million people. With this severe human resources shortage, many more pharmacists need to train and qualify before an impact on patient care can be seen. This is particularly true for clinical pharmacy, because the more traditional dispensary-based roles need to be filled before it can develop.

Part of this is about increasing the skill mix, and a new pharmacy technician course started in 2015. In the long run, this should allow technicians to fulfil traditional supply roles, freeing up pharmacists to get on to the wards and develop clinical pharmacy services.

Because pharmacists have not really been in the hospitals in a clinical capacity, there is a need to nurture interprofessional relationships and demonstrate the value of a clinical pharmacist within the team. Given the significance of some of the interventions picked up by the students on their rotations, I hope this integration will be smooth and natural.

What are you doing now you have returned to the UK?

I am now back in my previous job, working as senior lead clinical pharmacist at the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. UNAM School of Pharmacy already has links with universities in the UK and my department is also keen to develop links. I have provisionally been given permission to return to Namibia to teach for short periods, a couple of times a year.

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to Tim Rennie and the UNAM School of Pharmacy team, and the pharmacy department at Newcastle-upon-Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.