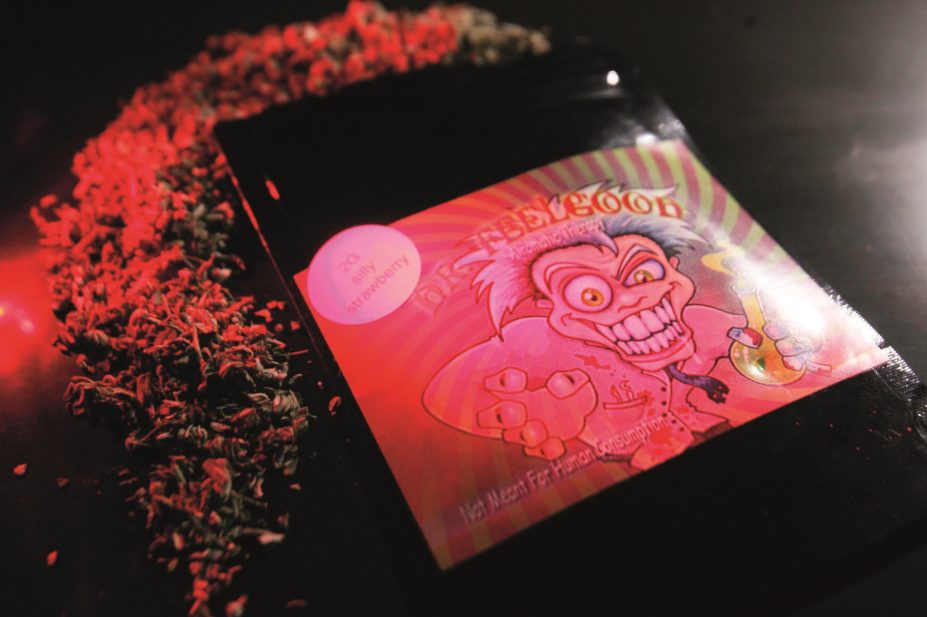

Eric Engman/Fairbanks Daily News-Miner/ZUMAPRESS.com) / Alamy.com

The UK government is introducing a bill that would bring a blanket ban on the production and supply of any drug that has a psychoactive effect in an effort to crack down on a wave of new recreational drugs.

The government wants to protect young people from the dangers of so-called ‘legal highs’ and target those who profit from these products, but some scientists have warned that the move could inhibit research into potentially useful new substances.

The plans, which aim to ban the “new generation of psychoactive drugs”, were announced in the Queen’s speech on 27 May 2015. The bill is so wide-reaching that products such as alcohol, tobacco, caffeine and certain medicines will be given a special exemption from the ban.

“The landmark bill will fundamentally change the way we tackle new psychoactive substances — and put an end to the game of cat and mouse in which new drugs appear on the market more quickly than government can identify and ban them,” says Mike Penning, the minister for policing, crime, criminal justice and victims.

In recent years there has been a wave of previously unseen drugs being used recreationally, with the government banning more than 500 new drugs. These include synthetic cannabinoids, the amphetamine mephedrone and gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), a central nervous system depressant.

An increasing number of deaths have been blamed on these substances; in 2013, there were 120 deaths involving new psychoactive substances in England, Scotland and Wales. In Scotland, there were 60 deaths in 2013 in which a new psychoactive substance was implicated, but for 55 of these deaths other substances were also implicated. However, these statistics have been described as misleading because many of the drugs classed as “new” or “legal” are already banned and/or have been around for some time. For example, in 2013 the ‘new psychoactive substance’ most often implicated in these deaths was phenazepam, a strong benzodiazepine used in Russia as a medicine since the mid-1970s, which was banned in the UK in June 2012.

And deaths involving p-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) are also included in these statistics, despite the fact it has been controlled in the UK since 1977.

Under the Psychoactive Substances Bill, the supply, production, import or export of any psychoactive substance, without an exemption, will carry a maximum term of seven years in prison.

However, the ban has been condemned by David Nutt, chair of Drug Science, a science-led drugs charity, which he set up after he was controversially fired in 2009 as chair of the government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Nutt argues that considering many of the drugs implicated in deaths attributed to “legal highs” are in fact already illegal, a further ban will make no difference.

He argues that a ban may lead to more deaths as it could cause supplies to be forced underground resulting in drugs of “uncertain provenance”. Instead, he advocates that the UK follows the Dutch model. The Netherlands has brought in national drugs testing facilities that allow users to find out if their drugs are pure or contaminated. “They have virtually eliminated deaths from new psychoactive substances,” says Nutt.

He also suggests the ban will affect the UK pharmaceutical industry and have a “serious unplanned impact” on research into new brain drugs. For example, he asks whether new antidepressant and anti-epilepsy drugs that are being studied now, or are yet to be discovered, could fall ‎under the ban.

The Home Office has assured that this will not be the case. It says all medicines and medicines in development will be exempt and no extra licenses will be needed for clinical trials of psychoactive drugs.

The bill was put before parliament on 29 May 2015.

You may also be interested in

What are the views of the RPS and Pharmaceutical Press on AI training using copyrighted materials?

Government should consider ways to prevent ‘inappropriate overseas prescribing’ of hormone drugs, review recommends