This content was published in 2012.

We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

When John Baker introduced the concept of ward pharmacy in the late 1960s at Westminster Hospital, London, it is probably safe to say that no one envisaged the transformation in practice that lay ahead. The advent of clinical pharmacy in the 1980s, embedding of specialist roles in the1990s and introduction of pharmacist supplementary, then independent, prescribing in the 2000s have led to many new career pathways for members of the profession. Pharmacists are now supporting patients both as individual clinicians and as key members of multidisciplinary teams.

Community pharmacy practice has developed to offer a wide range of services to enhance patient outcomes — emergency hormonal contraception, smoking cessation, minor ailment schemes, medicines use reviews, new medicine services and so on.

What use is excellence in prescribing practice if patients are unsure or unhappy about taking their medicines?

Having got to grips with providing clinical input into patientcare, the next challenge to address is in improving medicines adherence. What use is excellence in prescribing practice if patients are unsure or unhappy about taking their medicines? Although the provision of information and advice is an important aspect of the pharmacist-patient relationship, it can also be seen as overly directive and encouraging of dependence. We believe that pharmacists need to develop their skills in behavioural change to transform this relationship. Coaching provides a useful framework to support clinicians in developing consultation skills that encourage patients to engage with their own care. Pharmacists may already be familiar with motivational interviewing techniques, which form part of the health coaching skill set. A coaching-oriented approach acknowledges that the clinician is an expert in the field, but patients are the experts in their lives and therefore best placed to modify their behaviour and make plans for their health.

We wish to raise awareness among pharmacists of the impact they can have on medicines adherence, and to challenge them to consider making some relatively small changes in their practice that can yield huge benefits for patients.

Where does adherence fit?

There is good evidence underpinning the need to invest in supporting medicines adherence. The 2003 World Health Organization report “Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action” tells us that adherence to long-term medicines is around 50% in the developed world, less in developing countries, and that chronic conditions will affect over 65% of the global population by 2020. To quote the report: “Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have afar greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments”[1].

Optimising adherence support is justified through the Government’s “quality, innovation, productivity and prevention” (QIPP) challenge, which seeks to improve outcomes for patients through better health and to reduce preventable use of healthcare services. Furthermore, the financial implications of poor adherence were highlighted in the 2010 report “Evaluation of the scale, causes and costs of waste medicines”[2].

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence encourages a patient-centred approach to supporting adherence[3]. Research has demonstrated that telling patient show to behave is far less effective than helping patients to identify what outcomes they want and their methods for achieving these.

To maximise the impact our interventions can have on medicines optimisation, we must take up the challenge of optimising adherence. We need to ensure all pharmacists, whether based in primary or secondary care, whether practising as generalists or specialists, have the skills required to help patients get the best from their medicines.

What skills are needed?

So, in our day-to-day practice, how effective are we at supporting adherence? We have all had communication training over the years — do we not have the skills we need?

Let us consider the following example:

Mrs MB comes into your pharmacy with a new prescription for simvastatin. She presents it at the counter and waits for it to be dispensed. You call her name and she comes forward to receive the medicine. On questioning, she says she hasn’t taken the drug before, so you explain that the medicine is called simvastatin, which lowers cholesterol and has been given to her to reduce her risk of heart attack and stroke. You highlight the fact that she needs to take it at night and warn her to avoid grapefruit juice while taking the medicine. You alert her to the risk of muscle pain as a side effect and tell her that, if this happens, she needs to visit her GP. She thanks you, picks up the medicine and walks out of the pharmacy.

Sounds familiar so far. Well, here’s the end of this story…

You walk to the front of the pharmacy and you notice her walking down the street. She stops, takes out her bag of medicine, drops it in a nearby bin and walks on.

Is this scenario that far-fetched? Probably not, when we consider that up to 50% of medicines are not taken as intended. So, how might the consultation have been handled differently within the same timeframe?

What did we know about this patient? Arguably we knew next to nothing about her apart from the fact that she had not taken the medicine before. What if we had asked her what she knew about her condition, why the medicine had been prescribed or about the medicines itself? Could we have changed the outcome of the consultation?

Mrs MB comes into your pharmacy with a new prescription for simvastatin. She presents it at the counter and waits for it to be dispensed. You call her name and she comes forward to receive the medicine. You ask her what she knows about the her condition and the medicine. She tells you she doesn’t really know why she needs the drug and that she has read recently that the statins can have very dangerous side effects. You discuss this with her, explaining the benefits of risk reduction and asking her what side effects she is worried about. She tells you that she doesn’t know — it is just what was written in the paper. You reassure her about the low risk of side effects and that muscle pain is a good warning signal, so that if she is has this side effect it can be managed early. She agrees to try the simvastatin and see how it goes. You explain that the medicine is best taken at night and ask how she could integrate this into her daily routine. She says that she always has a glass of water with supper and that this would help her to remember to take it. She thanks you, picks up the medicine and walks out of the pharmacy.

To develop our practice to support adherence, we have to change our approach to consultations. Can we change the focus from telling to listening and responding with targeted information?

The use of coaching methods in healthcare settings — often called health coaching — has gained momentum in recent years. Within pharmacy, some practitioners already use motivational interviewing to encourage behavioural change in selected patient groups. Health coaching combines the practitioner’s clinical skills, the principles of health psychology and behavioural medicine, and the techniques of performance coaching to encourage patients to become active participants in their healthcare. This approach is particularly relevant for patients with chronic diseases who can benefit from ongoing self management. Moreover, the skills can be applied in five- to ten-minute consultations, making them ideal for MURs, the NMS or opportunistic “over the counter” conversations.

Training programmes for health coaching have been trialled in NHS Midlands and East and through the NHS London deanery with GPs, practice nurses and other healthcare professionals. Early results are promising, with patients reporting improvements in both their understanding of their condition, tests and treatments, and their ability to take appropriate action.

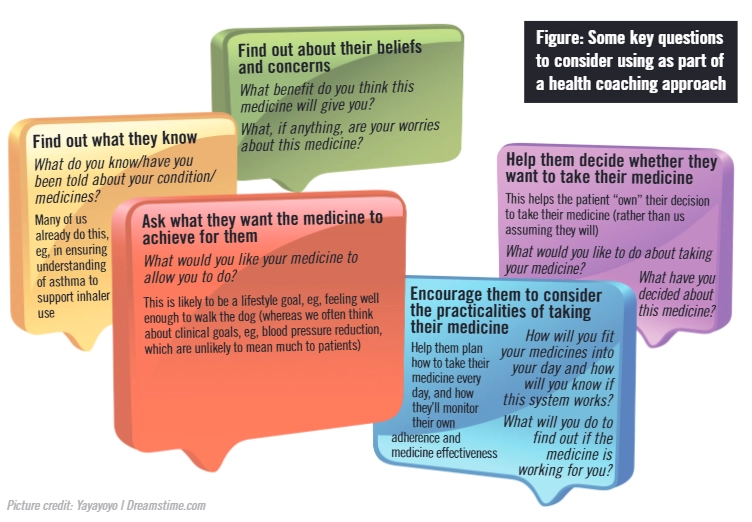

Consultations that focus on adherence, using techniques from health coaching, have three objectives:

- To raise a patient’s awareness of the importance of taking a medicine;

- To support a patient in taking responsibility for taking a medicine;

- To enable a patient to integrate taking a medicine into his or her lifestyle.

These objectives can be considered alongside some key questions (see Figure) for use within patient consultations — e.g., discharge counselling in hospitals and medicines use reviews in the community.

Medicines optimisation

Supporting good medicines adherence is part of medicines optimisation and is essential if we want to improve the return on investment in medicines — both for patients and for the NHS.

The need to provide accurate and appropriate information and education has never been greater. Yet to achieve successful outcomes our patients need to be more actively engaged in their care.

With relatively small changes in our practice — using a coaching approach to focus our attention on what we can learn from our patients — we can direct our education better to meet their needs.

References

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. January 2003. www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en (accessed 26 June 2012).

- York Health Economics Consortium and The School of Pharmacy, University of London. Evaluation of the scale, causes and costs of waste medicines. November 2010. http://php.york.ac.uk/inst/yhec/web/news/documents/Evaluation_of_NHS_Medicines_Waste_Nov_2010.pdf (accessed 26 June 2012).

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. January 2009. www.nice.org.uk/cg76 (accessed 26 June 2012).